Distal Phalangeal and Fingertip Injuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICD-10 Diagnoses on Router

L ARTHRITIS R L HAND R L ANKLE R L FRACTURES R OSTEOARTHRITIS: PRIMARY, 2°, POST TRAUMA, POST _____ CONTUSION ACHILLES TEN DYSFUNCTION/TENDINITIS/RUPTURE FLXR TEN CLAVICLE: STERNAL END, SHAFT, ACROMIAL END CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: GOUT: IDIOPATHIC, LEAD, CRUSH INJURY AMPUTATION TRAUMATIC LEVEL SCAPULA: ACROMION, BODY, CORACOID, GLENOID DRUG, RENAL, OTHER DUPUYTREN’S CONTUSION PROXIMAL HUMERUS: SURGICAL NECK 2 PART 3 PART 4 PART CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: PSEUDOGOUT: HYDROXY LACERATION: DESCRIBE STRUCTURE CRUSH INJURY PROXIMAL HUMERUS: GREATER TUBEROSITY, LESSER TUBEROSITY DEP DIS, CHONDROCALCINOSIS LIGAMENT DISORDERS EFFUSION HUMERAL SHAFT INFLAMMATORY: RA: SEROPOSITIVE, SERONEGATIVE, JUVENILE OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ LOOSE BODY HUMERUS DISTAL: SUPRACONDYLAR INTERCONDYLAR REACTIVE: SECONDARY TO: INFECTION ELSEWHERE, EXTENSION OR NONE INTESTINAL BYPASS, POST DYSENTERIC, POST IMMUNIZATION PAIN OCD TALUS HUMERUS DISTAL: TRANSCONDYLAR NEUROPATHIC CHARCOT SPRAIN HAND: JOINT? OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ HUMERUS DISTAL: EPICONDYLE LATERAL OR MEDIAL AVULSION INFECT: PYOGENIC: STAPH, STREP, PNEUMO, OTHER BACT TENDON RUPTURES: EXTENSOR OR FLEXOR PAIN HUMERUS DISTAL: CONDYLE MEDIAL OR LATERAL INFECTIOUS: NONPYOGENIC: LYME, GONOCOCCAL, TB TENOSYNOVITIS SPRAIN, ANKLE, CALCANEOFIBULAR ELBOW: RADIUS: HEAD NECK OSTEONECROSIS: IDIOPATHIC, DRUG INDUCED, SPRAIN, ANKLE, DELTOID POST TRAUMATIC, OTHER CAUSE SPRAIN, ANKLE, TIB-FIB LIGAMENT (HIGH ANKLE) ELBOW: OLECRANON WITH OR WITHOUT INTRA ARTICULAR EXTENSION SUBLUXATION OF ANKLE, -

Upper Extremity

Upper Extremity Shoulder Elbow Wrist/Hand Diagnosis Left Right Diagnosis Left Right Diagnosis Left Right Adhesive capsulitis M75.02 M75.01 Anterior dislocation of radial head S53.015 [7] S53.014 [7] Boutonniere deformity of fingers M20.022 M20.021 Anterior dislocation of humerus S43.015 [7] S43.014 [7] Anterior dislocation of ulnohumeral joint S53.115 [7] S53.114 [7] Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, upper limb G56.02 G56.01 Anterior dislocation of SC joint S43.215 [7] S43.214 [7] Anterior subluxation of radial head S53.012 [7] S53.011 [7] DeQuervain tenosynovitis M65.42 M65.41 Anterior subluxation of humerus S43.012 [7] S43.011 [7] Anterior subluxation of ulnohumeral joint S53.112 [7] S53.111 [7] Dislocation of MCP joint IF S63.261 [7] S63.260 [7] Anterior subluxation of SC joint S43.212 [7] S43.211 [7] Contracture of muscle in forearm M62.432 M62.431 Dislocation of MCP joint of LF S63.267 [7] S63.266 [7] Bicipital tendinitis M75.22 M75.21 Contusion of elbow S50.02X [7] S50.01X [7] Dislocation of MCP joint of MF S63.263 [7] S63.262 [7] Bursitis M75.52 M75.51 Elbow, (recurrent) dislocation M24.422 M24.421 Dislocation of MCP joint of RF S63.265 [7] S63.264 [7] Calcific Tendinitis M75.32 M75.31 Lateral epicondylitis M77.12 M77.11 Dupuytrens M72.0 Contracture of muscle in shoulder M62.412 M62.411 Lesion of ulnar nerve, upper limb G56.22 G56.21 Mallet finger M20.012 M20.011 Contracture of muscle in upper arm M62.422 M62.421 Long head of bicep tendon strain S46.112 [7] S46.111 [7] Osteochondritis dissecans of wrist M93.232 M93.231 Primary, unilateral -

2014 Newsletter – Winter

NEWS ISSUE 14 I WINTER 2014 Welcome to our Winter edition of Orthosports News Winter is the time when Alpine Injuries present themselves WHO ORTHOSPORTS – Dr Doron Sher covers the most common types of alpine ARE WE? LOCATIONS injuries. Dr Kwan Yeoh takes a look at Mallet Finger and Orthosports is > Concord 02 9744 2666 “Imaging of the knee” is covered by Dr Sher in our Key a professional > Hurstville 02 9580 6066 Examination Points Section. association of > Penrith 02 4721 7799 Many GPs have attended our Category 1 Education Modules; AOA Orthopaedic > Randwick 02 9399 5333 A USTRAL I A N ORTHOPA EDIC Surgeons based Or visit our website there are 4 remaining dates for our 2014 RACGP approved A S S O CIA T I O N modules. See page 4 for details. in Sydney. www.orthosports.com.au We hope you enjoy this issue – The Team at Orthosports elbow injuries and more comminuted clavicle fractures. Alpine Injuries Shoulder dislocation is also very common. Snowboarders do not usually injure their legs when both feet are attached Skiing and snowboarding are exhilarating sports. They to the board but injuries to the knee are not uncommon are physically demanding and require co-ordination, getting on and off lifts when only one foot is bound to the strength, fitness and lots of specialized equipment. More board (more common in beginners). If they do injure their people ski than snowboard and snowboarders are generally knee, it is almost always in a terrain park landing from younger than skiers. Skiing and snowboarding injuries a big jump. -

Hughston Health Alert US POSTAGE PAID the Hughston Foundation, Inc

HughstonHughston HealthHealth AlertAlert 6262 Veterans Parkway, PO Box 9517, Columbus, GA 31908-9517 • www.hughston.com/hha VOLUME 26, NUMBER 4 - FALL 2014 Fig. 1. Knee Inside... anatomy and • Rotator Cuff Disease ACL injury. Extended (straight) knee • Bunions and Lesser Toe Deformities Femur • Tendon Injuries of the Hand (thighbone) Patella In Perspective: (kneecap) Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears Medial In 1992, Dr. Jack C. Hughston (1917-2004), one of the meniscus world’s most respected authorities on knee ligament surgery, MCL LCL shared some of his thoughts regarding injuries to the ACL. (medial “You tore your anterior cruciate ligament.” On hearing (lateral collateral collateral your physician speak those words, you are filled with a sense ligament) of dread. You envision the end of your athletic life, even ligament) recreational sports. Today, a torn ACL (Fig. 1) has almost become a household Tibia word. Through friends, newspapers, television, sports Fibula (shinbone) magazines, and even our physicians, we are inundated with the hype that the knee joint will deteriorate and become arthritic if the ACL is not operated on as soon as possible. You have been convinced that to save your knee you must Flexed (bent) knee have an operation immediately to repair the ligament. Your surgery is scheduled for the following day. You are scared. Patella But there is an old truism in orthopaedic surgery that says, (kneecap) “no knee is so bad that it can’t be made worse by operating Articular Torn ACL on it.” cartilage (anterior For many years, torn ACLs were treated as an emergency PCL cruciate and were operated on immediately, even before the initial (posterior ligament) pain and swelling of the injury subsided. -

Hand Rehabilitation Current Awareness Newsletter

1 Hand Rehabilitation Current Awareness Newsletter JANUARY 2016 2 Your Local Librarian Whatever your information needs, the library is here to help. As your outreach librarian I offer literature searching services as well as training and guidance in searching the evidence and critical appraisal – just email me at library @uhbristol.nhs.uk OUTREACH: Your Outreach Librarian can help facilitate evidence-based practise for all in the Orthogeriatrics team, as well as assisting with academic study and research. We can help with literature searching, obtaining journal articles and books, and setting up individual current awareness alerts. We also offer one-to-one or small group training in literature searching, accessing electronic journals, and critical appraisal. Get in touch: [email protected] LITERATURE SEARCHING: We provide a literature searching service for any library member. For those embarking on their own research it is advisable to book some time with one of the librarians for a 1 to 1 session where we can guide you through the process of creating a well-focused literature research and introduce you to the health databases access via NHS Evidence. Please email requests to [email protected] 3 Contents New from Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ........................................................................... 4 Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. 4 New Activity in Up-to-Date .................................................................................................................... -

Page 1 of 4 COPYRIGHT © by the JOURNAL of BONE and JOINT SURGERY, INCORPORATED LAMPLOT ET AL

COPYRIGHT © BY THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY, INCORPORATED LAMPLOT ET AL. RISK OF SUBSEQUENT JOINT ARTHROPLASTY IN CONTRALATERAL OR DIFFERENT JOINT AFTER INDEX SHOULDER, HIP, OR KNEE ARTHROPLASTY http://dx.doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.17.00948 Page 1 Appendix TABLE E-1 Included Alternative Primary Diagnoses ICD-9-CM Code Diagnosis* 716.91 Arthropathy NOS, shoulder 716.95 Arthropathy NOS, pelvis 716.96 Arthropathy NOS, lower leg 719.45 Joint pain, pelvis 719.91 Joint disease NOS, shoulder *NOS = not otherwise specified. Page 1 of 4 COPYRIGHT © BY THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY, INCORPORATED LAMPLOT ET AL. RISK OF SUBSEQUENT JOINT ARTHROPLASTY IN CONTRALATERAL OR DIFFERENT JOINT AFTER INDEX SHOULDER, HIP, OR KNEE ARTHROPLASTY http://dx.doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.17.00948 Page 2 TABLE E-2 Excluded Diagnoses* ICD-9- ICD-9- ICD-9- ICD-9- CM Code Diagnosis CM Code Diagnosis CM Code Diagnosis CM Code Diagnosis 274 Gouty arthropathy NOS 696 Psoriatic 711.03 Pyogen 711.38 Dysenter arthropathy arthritis- arthritis NEC forearm 274.01 Acute gouty arthropathy 696.1 Other psoriasis 711.04 Pyogen 711.4 Bact arthritis- arthritis-hand unspec 274.02 Chr gouty arthropathy 696.2 Parapsoriasis 711.05 Pyogen 711.46 Bact arthritis- w/o tophi arthritis-pelvis l/leg 274.03 Chr gouty arthropathy w 696.3 Pityriasis rosea 711.06 Pyogen 711.5 Viral arthritis- tophi arthritis-l/leg unspec 274.1 Gouty nephropathy NOS 696.4 Pityriasis rubra 711.07 Pyogen 711.55 Viral arthritis- pilaris arthritis-ankle pelvis 274.11 Uric acid nephrolithiasis 696.5 Pityriasis NEC & 711.08 -

Hand Deformities in Rheumatoid Disease

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.16.2.183 on 1 June 1957. Downloaded from Ann. rheum. Dis. (1957), 16, 183. HAND DEFORMITIES IN RHEUMATOID DISEASE BY D. A. BREWERTON From the Department of Physical Medicine, King's College Hospital, London (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION FEBRUARY 1, 1957) This is a study of hand deformities in rheumatoid rheumatic disease; fifteen were seen in the wards. None disease: their incidence, their causes, and their was bedridden. The sex ratio, age at onset, and duration of disease are effects on function. Three hundred patients with set out in Tables I and II. All age groups are repre- this disease have been examined. sented, except that, by chance, there were no men in There can be no doubt of the importance of hand whom the disease had started when under 20 years of deformities to the rheumatoid patient, nor of the age. Almost half of the patients were in the first 5-year importance of preventing hand deformities when period of disease, but after that period their numbers treating this disease. Consequently it is surprising steadily decreased, because of the artificial selection of to find that there are few detailed accounts of these hospital out-patients. Presumably many in the later deformities in the literature. Ulnar deviation and years no longer attend as they have improved; a few are its causes have been discussed at length (Fearnley, too disabled; and the rest have returned to the care of their general practitioners. Certainly those still attend- copyright. 1951; Lush, 1952; Vainio and Oka, 1953). -

Hand and Finger-DBQ

INTERNAL VETERANS AFFAIRS USE HAND AND FINGER CONDITIONS DISABILITY BENEFITS QUESTIONNAIRE IMPORTANT - THE DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS (VA) WILL NOT PAY OR REIMBURSE ANY EXPENSES OR COST INCURRED IN THE PROCESS OF COMPLETING AND/OR SUBMITTING THIS FORM. PLEASE READ THE PRIVACY ACT AND RESPONDENT BURDEN INFORMATION ON REVERSE BEFORE COMPLETING FORM. NAME OF PATIENT/VETERAN PATIENT/VETERAN'S SOCIAL SECURITY NUMBER NOTE TO PHYSICIAN - Your patient is applying to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for disability benefits. VA will consider the information you provide on this questionnaire as part of their evaluation in processing the veteran's claim. IS THIS QUESTIONNAIRE BEING COMPLETED IN CONJUNCTION WITH A VA21-2507, C&P EXAMINATION REQUEST? YES NO How was the examination completed? (check all that apply) In-person examination Records reviewed Examination via approved video telehealth Other, please specify in comments box: Comments: ACCEPTABLE CLINICAL EVIDENCE (ACE) INDICATE METHOD USED TO OBTAIN MEDICAL INFORMATION TO COMPLETE THIS DOCUMENT: Review of available records (without in-person or video telehealth examination) using the Acceptable Clinical Evidence (ACE) process because the existing medical evidence provided sufficient information on which to prepare the questionnaire and such an examination will likely provide no additional relevant evidence. Review of available records in conjunction with an interview with the Veteran (without in-person or telehealth examination) using the ACE process because the existing medical -

Common Hand, Wrist and Elbow Problems

12/15/2018 COMMON HAND, WRIST Disclosures AND ELBOW PROBLEMS: Research Support: HOW TO SPOT THEM IN San Francisco DPH CLINIC Standard Cyborg Nicolas H. Lee, MD UCSF Dept of Orthopaedic Surgery Assistant Clinical Professor Hand, Upper Extremity and Microvascular Surgery Dec. 15th, 2018 DIP joint pathologies Mucous Cyst – ganglion cyst of DIP joint 1. Mucous Cyst 2. Mallet Finger 3. Jersey Finger 1 12/15/2018 Xray Treatment “Jammed Finger” Mallet Finger • Recurrence rate with aspiration/needling? 40-70% • Recurrence rate with surgical debridement of osteophyte? Jersey Finger 0-3% • Do nail deformities resolve with surgery? Yes - 75% 2 12/15/2018 Mallet Finger Mallet finger Soft Tissue Mallet • 6 weeks DIP immobilization in extension • Night time splinting for 4 weeks Bony Mallet http://www.specialisedhandtherapy.com.au/ Red Flag Mallet Finger Red Flag Jersey Finger When to Refer: Flexor Digitorum Profundus (FDP) 1. Big fragment strength testing 2. Volar subluxation of the distal phalanx http://nervesurgery.wustl.edu/ http://www.orthobullets.com REFER ALL JERSEY FINGERS ASAP!!! 3 12/15/2018 Trigger Finger and Thumb Trigger finger • Presentation • Clicking or frank locking • Especially at night or morning • May also present with just pain at the A1 pulley Trigger Finger Primary Trigger Finger • Physical Examination • Most Common • Locking or clicking over the A1 pulley • “Idiopathic” • Tenderness at the A1 pulley • No known cause 4 12/15/2018 Secondary “Congenital” • Associated with known disease • Infantile form • Disease cause thickening in tendon/pulley • “congenital” is a misnomer • Diabetes • Rheumatoid arthritis • Amyloidosis • Sarcoidosis Treatment Options Trigger finger Splinting •Nonoperative • Splint to prevent MCP or •Observation PIP flexion. -

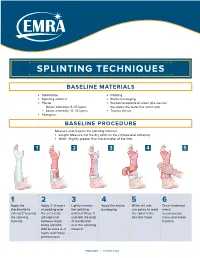

Splinting Techniques

SPLINTING TECHNIQUES BASELINE MATERIALS l Stockinette l Padding l Splinting material l Elastic bandaging l Plaster l Bucket/receptacle of water (the warmer — Upper extremity: 8–10 layers the water, the faster the splint sets) — Lower extremity: 10–12 layers l Trauma shears l Fiberglass BASELINE PROCEDURE Measure and prepare the splinting material. l Length: Measure out the dry splint on the contralateral extremity l Width: Slightly greater than the diameter of the limb 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Apply the Apply 2–3 layers Lightly moisten Apply the elastic While still wet, Once hardened, stockinette to of padding over the splinting bandaging. use palms to mold check extend 2" beyond the area to be material. Place it the splint to the neruovascular the splinting splinted and and fold the ends desired shape. status and motor material. between digits of stockinette function. being splinted. over the splinting Add an extra 2–3 material. layers over bony prominences. EMRA.ORG | 972.550.0920 POSTERIOR LONG ARM VOLAR SPLINT SPLINT INDICATIONS INDICATIONS l Olecranon fractures l Soft tissue injuries of the hand and wrist l Humerus fractures l Carpal bone fractures l Radial head and neck fractures l 2nd–5th metacarpal head fractures CONSTRUCTION CONSTRUCTION l Start at posterior proximal arm l Start at palm at the metacarpal heads l Down the ulnar forearm l Down the volar forearm l End at the metacarpophalangeal joints l End at distal forearm APPLICATION APPLICATION l Cut hole in stockinette for thumb l Cut hole in stockinette for thumb l Elbow at 90º -

Hand, Wrist and Elbow Problems: How to Spot Them in Clinic

11/27/2017 HAND, WRIST AND ELBOW PROBLEMS: HOW TO SPOT THEM IN CLINIC Nicolas H. Lee, MD [email protected] UCSF Dept of Orthopaedic Surgery Assistant Clinical Professor Hand, Upper Extremity and Microvascular Surgery Dec. 3rd, 2017 Disclosures Research Support: San Francisco DPH Standard Cyborg 1 11/27/2017 DIP joint pathologies 1. Mucous Cyst 2. Mallet Finger 3. Jersey Finger Mucous Cyst – ganglion cyst of DIP joint 2 11/27/2017 Xray 3 11/27/2017 Treatment • Recurrence rate with aspiration/needling? 40-70% • Recurrence rate with surgical debridement of osteophyte? 0-3% • Do nail deformities resolve with surgery? Yes - 75% “Jammed Finger” Mallet Finger Jersey Finger 4 11/27/2017 Mallet Finger Soft Tissue Mallet Bony Mallet http://www.specialisedhandtherapy.com.au/ Mallet finger • 6 weeks DIP immobilization in extension • Night time splinting for 4 weeks 5 11/27/2017 Red Flag Mallet Finger When to Refer: 1. Big fragment 2. Volar subluxation of the distal phalanx Red Flag Jersey Finger Flexor Digitorum Profundus (FDP) strength testing http://nervesurgery.wustl.edu/ http://www.orthobullets.com REFER ALL JERSEY FINGERS ASAP!!! 6 11/27/2017 Trigger Finger and Thumb Trigger finger • Presentation • Clicking or frank locking • Especially at night or morning • May also present with just pain at the A1 pulley 7 11/27/2017 Trigger Finger • Physical Examination • Locking or clicking over the A1 pulley • Tenderness at the A1 pulley Primary Trigger Finger • Most Common • “Idiopathic” • No known cause 8 11/27/2017 Secondary • Associated with known disease • Disease cause thickening in tendon/pulley • Diabetes • Rheumatoid arthritis • Amyloidosis • Sarcoidosis “Congenital” • Infantile form • “congenital” is a misnomer 9 11/27/2017 Treatment Options •Nonoperative •Observation •Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication Studies show •Splinting steroid injection alone is more •Corticosteroid injection effective than splints •Operative release Trigger finger Splinting • Splint to prevent MCP or PIP flexion. -

Mallet Finger Injuries

Give Me Back My Hand and Fingers- Part 2 Thomas V Gocke, MS, ATC, PA-C, DFAAPA President/Founder Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. Boone, North Carolina www.orthoedu.com [email protected] Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. © 2016 Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. all rights reserved. Faculty Disclosures • Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. Financial Intellectual Property No off label product discussions American Academy of Physician Assistants Financial PA Course Director, PA’s Guide to the MSK Galaxy Urgent Care Association of America Financial Intellectual Property Faculty, MSK Workshops Ferring Pharmaceuticals Consultant Orthopaedic 2 Educational Services, Inc. © 2016 Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. all rights reserved. Learning Goals Attendees will be able to develop skills in the assessment of ……….. • Hand/Finger Extensor Tendon Injuries • Hand/Finger Flexor Tendon Injuries • Human/Fight Bite wounds to the Fingers • Finger High Pressure Injection Injuries • Metacarpalphalangeal (MCP) joint dislocations • Phalanx fractures • Finger tip trauma Orthopaedic 3 Educational Services, Inc. © 2016 Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. all rights reserved. Boutonniere Finger Injuries Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. © 2016 Orthopaedic Educational Services, Inc. all rights reserved. • Boutonniere Deformity • Zone II extensor injury • Affects PIP & DIP joints – Extrinsic mechanism: Extensor Digitorium Communis (EDC) – Intrinsic mechanism: Lumbricals • Injury Mechanism – Rupture central slip extensor tendon/hood