Scottish Affairs Page Setup

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2015 Meet the Masters: Highlights from the Scottish National Gallery The Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch Angus Trumble 15/16 July 2015 Lecture summary: The Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch, c. 1798-1800, has not only become synonymous with the art of Sir Henry Raeburn, but has also assumed the character of an icon of the Scottish enlightenment, and of Scottish painting itself. Ten years ago, in a long article in the Burlington Magazine, Stephen Lloyd cast serious doubt upon the attribution to Raeburn on various grounds, and proposed instead that this action portrait was instead painted by the Frenchman Henri-Pierre Danloux. The ensuing controversy, and rebuttal, has shed much new light on the picture, and indeed the artist, but raises far broader questions as to the relationship between “technical” art history and connoisseurship. What are the limitations of each, and both in sometimes fraught dialogue? If, as is generally accepted, while iconic, The Reverend Robert Walker is a very unusual product of Raeburn’s studio, just how unusual can a picture be, at least in what used to be called an artist’s oeuvre, to raise and justify doubts as to its authorship? What factors, including a relatively secure provenance and close, not to say intense “looking,” may legitimately be marshalled in defence of the longstanding attribution to Raeburn? What is the role of scholarly consensus or, indeed, dissent in these debates? Slide list: 1. Henry Raeburn, The Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch, c. 1798-1800, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh (I shall return again and again to this image) 2. -

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

Mary, Queen of Scots at the Palace of Holyroodhouse Information for Teachers

PALACE OF HOLYROODHOUSE Mary, Queen of Scots at the Palace of Holyroodhouse Information for Teachers Planning Your Visit We hope you enjoy your visit to the Palace of Holyroodhouse. Before you arrive, please read this information to help you make the most of your time here. Frequently Asked Questions Is my booking confirmed? The attached letter is your confirmation. Please read it carefully and if the details are not correct please telephone us on 0131 557 2500. If there are any fees due on your booking, your letter will confirm the date by which full payment must be received. All bookings are made subject to our terms and conditions, which are available on request. Can I make changes to the size of my group? You can confirm any increase in the number of your group up to 24 hours in advance of your visit. Please note, if you would like to book additional accompanying adults, above the stated ratios, a reduced-rate admission fee of £3 per adult will be payable. How do I arrange a complimentary planning visit? If you and a colleague would like to make a planning trip before your group visit, please contact the Learning Bookings Team to arrange this. Two complimentary tickets will be booked for you, for collection on the day. If you would like to meet a member of the Learning Team or see the Learning Rooms during your planning visit, please advise us during booking. Is there a lunch room at the Palace? There is limited space for eating packed lunches in the Learning Rooms. -

Written Guide

The tale of a tail A self-guided walk along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile ww.discoverin w gbrita in.o the stories of our rg lands discovered th cape rough w s alks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Credits © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2015 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail from the Scottish Parliament Building © Rory Walsh RGS-IBG Discovering Britain 3 The tale of a tail Discover the stories along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile A 1647 map of The Royal Mile. Edinburgh Castle is on the left Courtesy of www.royal-mile.com Lined with cobbles and layered with history, Edinburgh’s ‘Royal Mile’ is one of Britain’s best-known streets. This famous stretch of Scotland’s capital also attracts visitors from around the world. This walk follows the Mile from historic Edinburgh Castle to the modern Scottish Parliament. The varied sights along the way reveal Edinburgh’s development from a dormant volcano into a modern city. Also uncover tales of kidnap and murder, a dramatic love story, and the dramatic deeds of kings, knights and spies. The walk was originally created in 2012. It was part of a series that explored how our towns and cities have been shaped for many centuries by some of the 206 participating nations in the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. -

Scottish Parliament Building Edinburgh, Scotland

Scottish Parliament Building Client: Location: Edinburgh, Scotland Date: Typology: In 1998 EMBT won the bid to design the new Edinburgh Parliament building. The Architect: proposal generated great enthusiasm due to its organic capacity to combine existing Project directors: elements with new technologies through the contemporary and unique language of the Design team: Barcelona studio. The project’s development centered on reflecting the characteristics Gross floor area: of the country and its inhabitants via a new way of building that was directly linked to the land itself. This close tie to the site and its setting would, when the adjacent distillery is demolished, enable the generation of multiple perspective lines on the city. Intentionally, a contrast is sought, a conceptual distance, between the new construction and Holyrood Palace, the twelfth-century royal residence that has been renovated many times. Unlike the palace, which dominates the landscape, the new Scottish Parliament drops literally into the hillside terrain, the lowest part of Arthur’s Seat, and appears to sprout from the living stone. Client: The Scottish Executive Government Location: Edinburgh, Scotland Date: 2004 Typology: Civic Government, Landscape Architects: Enric Miralles, Benedetta Tagliabue in a joint venture with: RMJM Scotland LTD, M.A.H Duncan, T.B. Stewart EMBT Staff Competition: Joan Callis, project leader. Constanza Chara, Omer Arbel, Fabian Asunción, Steven Bacaus, Michael Eichhorn, Christopher Hitz, Francesco Mozzati. Leonardo Giovanozzi, Fergus Mc Ardle, Fernanda Hannah, Annie Marcela Henao, Ricardo Jimenez. Project: Joan Callis, project leader. Karl Unglaub, site architect Constanza Chara Umberto Viotto, Michael Eichhorn, Fabian Asunción, Fergus Mc Ardle, Sania Belli , Gustavo Silva Nicoletti, Vicenzo Franza , Antonio Benaduce, Andrew Vrana, Bernardo Ríos, Torsten Skoetz, Tomoko Sakamoko, Javier García Germán,. -

FRIENDS of BRUTON 11 Day Tour of Scotland and England June 17-27, 2016 Dear Friend

FRIENDS OF BRUTON 11 Day Tour of Scotland and England June 17-27, 2016 Dear Friend: We are eagerly anticipating this faith-based excursion to the U.K. The Friends of Bruton Parish Church, Williamsburg, Virginia is sponsoring the pilgrimage. The Friends of Bruton has led a previous pilgrimage and the positive response to that trip encouraged us to organize another. Knowing that Bruton Parish Church is one of the most historic parishes in the country, you can expect an emphasis on history. Looking at our itinerary, I hope you recognize the opportunity to tell significant stories of history and faith. We will have a tour leader, who will ground us in points of interest and facts. As our spiritual guide, I will do a number of reflections to open our hearts to things of the Spirit. We are in the midst of conversations with our Church of England family for some behind the scenes peeks into the special places we are set to visit. Again, reflecting upon our schedule and the sites we will visit, this is a unique tour for those seeking something more than your typical English tour. From Iona to York, you will experience a different side of the U.K. My hope is to gather together a group of individuals and facilitate our development as a community. It will be my pleasure and privilege to be with you as we discover another side of the U.K. Faithfully, The Revd Christopher L. Epperson Rector ITINERARY DAY 1: Friday, June 17 - Washington, DC/En Route Depart from Washington, DC for your overnight trans-Atlantic flight to Edinburgh. -

Concerts & Castles

Concerts & Castles A Magical Journey to Scotland with WBJC! August 2-12, 2018 Tour begins August 3rd in Scotland. Jonathan Palevsky has been with WBJC since 1986 and has been the station’s Program Director since 1990. He is originally from Montreal and came to Baltimore in 1982 to study classical guitar at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University. Edinburgh seen from Calton Hill On WBJC he is the host of the WBJC Opera Preview, the music review program Face the Music, Music in Maryland, and is Join the indefatigable Jonathan Palevsky co-host of Word on Wine. His current off-air obsessions include for another magical musical journey, this skiing, playing guitar and being the host of Cinema Sundays. Simon Rattle time to bonnie Scotland. The highlight is attendance at the 71st annual Edinburgh International Festival, arguably the world’s best arts festival, in one of Europe’s most beautiful capitals. A mark of this great event, you will enjoy a wide variety of performances including two H H H H by the London Symphony led by its new music director Sir Simon Rattle, Tour Highlights back home after his long tenure with the Berlin Philharmonic; a production • Prime tickets to five of Rossini’s sparkling The Barber of Seville from Paris; recitals by the performances at the superb pianists Piotr Anderszewski and Marc-André Hamelin, the latter Edinburgh Festival, including an opera, two with the Takacs Quartet; and the spectacular Royal Military Tattoo, beneath orchestral concerts, and two recitals Edinburgh Castle. You will also have the option of attending a concert • Prime tickets to the Royal Military Tattoo at Edinburgh Castle performance of Wagner’s Siegfried with a first-rate cast, or the National • Optional concert of Wagner’s Siegfried, or a play by Theatre of Scotland’s amazing chamber musical, Midsummer, the National Theatre of Scotland set in Edinburgh. -

Notes on James Fifth's Towers, Holyrood Palace

I. NOTES ON JAMES FIFTH'S TOWERS, HOLYROOD PALACE. BY JOHN SINCLAIR, F.S.A. SCOT. Wo may question if in the whole of Scotland there is one spot which is better know r morno e deeply impressed with tragic associations than e Holyrooth f Mar o dn countryme yow r Stuart t onlou t No o bu ynt . e Englisth o t h speaking nations becomha t i s ea pilgrimag f neveo e r failing interest e devoted eveth an ;n ni e from foreign nca lando wh s only mutter the words ' Marie Stuart' as he finds his way through the old Towers e samth , e keen sens f profouneo d interes s manifesti t e Th . regal pala^ Falklandf so , Linlithgow d Stirling'an , s towering stronghold have each their tale f strif so rold f birtho an le royad san l Stuart deaths, store th f Mart yo bu y Stuart' x yearssi s ' miserr father'he n yi s Towers of Holyroo mads dha indelibln ea e mar Scottisn ki h history. NOTES ON JAMES FIFTH'S TOWERS, HOLYKOOD PALACE. 225 Wha s beeha t n often designate s descriptiva d e treatmen f Jameo t s Fifth's Towert lefwithous u ye t s ha s t one thorough exposition, eithef ro their external elevation and varied changes, or of their curious and somewhat intricate interiors in which so many historic and tragic events have occurred. Even in the Proceedings of this Society there is a singu- lar paucity of that exact periodical tracing which we expect to find from the study of such a deeply interesting pile. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

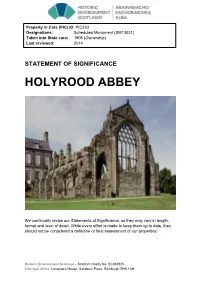

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

SCOTLAND September 6-15, 2019

DISCOVER SCOTLAND September 6-15, 2019 WITH NHPBS AND WILLEM LANGE Travel in the footsteps of the Jacobite revolution and ancient Scots on the journey of a lifetime that will highlight the rugged natural beauty, intriguing history, and delightful modern charm of Scotland. New Hampshire PBS and American Expeditions invite you to discover the enchanting land of Scotland with New England’s favorite storyteller, Willem Lange. Surrounded by lore and shrouded in mystery, the mere mention of Scotland conjures images of imposing castles, untamed landscapes, soft strains of bagpipes, and a plethora of historical legends. Take a step back in time as we take in sweeping and verdant natural wonders, remote sea-sprayed ruins, and stroll the iconic cobblestones of the Royal Mile on this unique and insightful Scottish experience that you will cherish for years to come. We begin in Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city which is situated in the Lowlands along the River Clyde. While just a small town upon Scotland’s union with England in 1707, it eventually blossomed into a thriving Victorian paradise as shipbuilding and steel production began to prosper in the 19TH century. Having honorably been named a European Capital of Culture in 1990, Glasgow rivals Edinburgh in the arts, with a thriving music scene and notable galleries and museums that honor its proud industrial heritage. Next, we’ll make our way up to the coastal town of Oban with a delightful stop in Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, whose natural beauty has inspired artists and writers for centuries, including Sir Walter Scott. -

The Tale of a Tail

The tale of a tail A self-guided walk along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile ww.discoverin w gbrita in.o the stories of our rg lands discovered th cape rough w s alks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Credits 30 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2015 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail from the Scottish Parliament Building © Rory Walsh RGS-IBG Discovering Britain 3 The tale of a tail Discover the stories along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile A 1647 map of The Royal Mile. Edinburgh Castle is on the left Courtesy of www.royal-mile.com Lined with cobbles and layered with history, the Royal Mile is one of the major routes in Edinburgh. Visitors come from worldwide to explore it’s charming alleys and vibrant shops. This famous street links Edinburgh Castle with The Palace of Holyrood and these buildings and others between them are familiar and popular attractions. This walk explores some of the stories behind the Royal Mile. Along the way we’ll follow Edinburgh’s development, from an ancient town built below a dormant volcano to a modern city built on international trade. We’ll discover tales of kidnap and murder, hear dramatic love stories and find out the deeds of kings, knights and spies. We’ll also find out why the Royal Mile isn’t as it seems! The walk was originally created in 2012.