Semantics and Pragmatics of Color Terms in Chinese∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flower Colors of Hardy Hybrid Rhododendrons

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the , BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 9 JULY 1, 1949 NUMBERS 7-8 FLOWER COLORS OF HARDY HYBRID RHODODENDRONS hybrid broad-leaved evergreen rhododendrons are most conspicuous dur- THEing early June. If grown in fertile, acid soil, mulched properly and pruned properly (see ARNOLDIA, Vol. 8, No. 8, September, 1948) they should pro- duce a bright display of flowers annually. The collection in the Arnold Arbore- tum is over fifty years old and has been added to continually from year to year. Rhododendron enthusiasts are continually studying this collection, noting the differences between the many varieties now being grown. Not all that are avail- able in the eastern United States nurseries are here, but many are, and it serves a valuable purpose, at the same time making a splendid display. It is most difficult to properly identify the many hardy rhododendron hybrids. The species are of course keyed out in standard botanical keys, but there is little easily available information about the identification of hybrids grown in the East. There are no colored pictures or paintings sufficiently accurate for this purpose, nor are there suitable descriptions of the flower colors. Articles for popular peri- odicals are numerous, but color descriptions in these are entirely too general. The term "crimson flowers" may cover a dozen or more varieties, each one of which does differ slightly from the others. Size of truss, of flower, markings on corolla and even the color of the stamens and pistils are all aides in identification. Consequently, we have started an attempt at the proper description of hybrid varieties, growing in our collection, by the careful comparison of colors of the flowers as they bloomed this year, with the colors of the Royal Horticultural Society’s Colour Chart. -

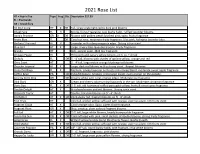

2021 Rose List HT = Hybrid Tea Type Frag Dis

2021 Rose List HT = Hybrid Tea Type Frag Dis. Description $27.99 FL = Floribunda GR = Grandiflora All My Loving HT X DR Tall, large single light red to dark pink blooms Angel Face FL X Strong, Citrus Fragrance. Low bushy habit, ruffled lavander blooms. Anna's Promise GR X DR Blooms with golden petals blushed pink; spicy, fruity fragrance Arctic Blue FL DR Good cut rose, moderate fruity fragrance. Lilac pink, fading to lavander blue. Barbara Streisand HT X Lavender with a deep magenta edge. Strong citrus scent. Blue Girl HT X Large, silvery liliac-lavender blooms. Fruity fragrance. Brandy HT Rich, apricot color. Mild tea fragrance. Chicago Peace HT Phlox pink and canary yellow blooms on 6' to 7' shrub Chihuly FL DR 3' - 4' tall, blooms with shades of apricot yellow, orange and red Chris Evert HT 3' - 4' tall, large melon orange blushing red blooms Chrysler Imperial HT X Large, dark red blooms with a strong scent. Repeat bloomer Cinco De Mayo FL X Medium, smoky lavender and rusty red-orange blend, moderate sweet apple fragrance Coffee Bean PA DR Patio/Miniature. Smokey, red-orange inside, rusty orange on the outside. Coretta Scott King GR DR Creamy white with coral, orange edges. Moderate tea fragrance. Dick Clark GR X Cream and cherry color turning burgundy in the sun. Moderate cinnamon fragrance. Doris Day FL X DR 3'-5' tall, old-fashioned ruffled pure gold yellow, fruity & sweet spice fragrance Double Delight HT X Bi-colored cream and red blooms. Strong spice scent. Elizabeth Taylor HT Double, hot-pink blooms on 5' - 6' shrub Firefighter HT X DR Deep dusky red, fragrant blooms on 5' - 6' shrub First Prize HT Very tall, golden yellow suffused with orange, vigorous plant, rich fruity scent Fragrant Cloud HT X Coral-orange color. -

Rose Problems

Page 1 of 7 Visit us on the Web: www.gardeninghelp.org A Visual Guide: Rose Problems Black spot of rose Black spot is the most important disease of roses and one of the most common diseases found everywhere roses are grown. The disease does not kill the plant outright, but over time, the loss of leaves can weaken the plant making it more susceptible to other stresses and to winter damage. Black spots, one-tenth to one-half inch in diameter, develop first on upper leaf surfaces. Later, areas adjacent to the black spots turn yellow and leaves drop prematurely, usually beginning at the bottom of the plant and progressing upward. Lookalikes: Spot anthracnose (shot-hole disease) is not a major problem unless it is very hot (too hot for black spot). Spots caused by black spot are fuzzy around the edges, then turn yellow and brown. Spots caused by anthracnose are smooth edged and the centers turn grey and drop out. Treatment is the same, but if a pesticide is used, it must be labeled for black spot or anthracnose, whichever disease you are treating. Rose rosette Rose rosette disease, also known as witches'-broom of rose, is a virus or virus-like disease, that is spread by a microscopic eriophyid mite. The main symptom is a tightly grouped, proliferation of distorted, usually bright red foliage (a witches'-broom). Affected canes may be excessively thorny, thicker than unaffected canes and slow to mature. The canes are also soft, as are the prickles, and will break off with little pressure. -

Color Names Across Languages: Salient Colors and Term Translation in Multilingual Color Naming Models

EUROVIS 2019/ J. Johansson, F. Sadlo, and G. E. Marai Short Paper Color Names Across Languages: Salient Colors and Term Translation in Multilingual Color Naming Models Younghoon Kim, Kyle Thayer, Gabriella Silva Gorsky and Jeffrey Heer University of Washington orange brown red yellow green pink English gray black purple blue 갈 빨강 노랑 주황 연두 자주 초록 회 분홍 Korean 청록 보라 하늘 검정 남 연보라 파랑 Figure 1: Maximum probability maps of English and Korean color terms. Each point represents a 10 × 10 × 10 bin in CIELAB color space. Larger points have a greater likelihood of agreement on a single term. Each bin is colored using the average color of the most probable name term. Bins with insufficient data (< 4 terms) are left blank. English has 10 clusters corresponding to basic English color terms [BK69], whereas Korean exhibits additional clusters for ¨ ( ), ] ( ), 자주 ( ), X늘 ( ), 연P ( ), and 연보| ( ). Abstract Color names facilitate the identification and communication of colors, but may vary across languages. We contribute a set of human color name judgments across 14 common written languages and build probabilistic models that find different sets of nameable (salient) colors across languages. For example, we observe that unlike English and Chinese, Russian and Korean have more than one nameable blue color among fully-saturated RGB colors. In addition, we extend these probabilistic models to translate color terms from one language to another via a shared perceptual color space. We compare Korean-English trans- lations from our model to those from online translation tools and find that our method better preserves perceptual similarity of the colors corresponding to the source and target terms. -

Color Dictionaries and Corpora

Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27851-8_54-1 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 Color Dictionaries and Corpora Angela M. Brown* College of Optometry, Department of Optometry, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA Definition In the study of linguistics, a corpus is a data set of naturally occurring language (speech or writing) that can be used to generate or test linguistic hypotheses. The study of color naming worldwide has been carried out using three types of data sets: (1) corpora of empirical color-naming data collected from native speakers of many languages; (2) scholarly data sets where the color terms are obtained from dictionaries, wordlists, and other secondary sources; and (3) philological data sets based on analysis of ancient texts. History of Color Name Corpora and Scholarly Data Sets In the middle of the nineteenth century, color-name data sets were primarily from philological analyses of ancient texts [1, 2]. Analyses of living languages soon followed, based on the reports of European missionaries and colonialists [3, 4]. In the twentieth century, influential data sets were elicited directly from native speakers [5], finally culminating in full-fledged empirical corpora of color terms elicited using physical color samples, reported by Paul Kay and his collaborators [6, 7]. Subsequently, scholarly data sets were published based on analyses of secondary sources [8, 9]. These data sets have been used to test specific hypotheses about the causes of variation in color naming across languages. From the study of corpora and scholarly data sets, it has been known for over 150 years that languages differ in the number of color terms in common use. -

Old Garden Roses

Old Garden Roses Old Garden Roses are the classic old-fashioned roses developed in England, Europe, and the Middle East prior to the introduction of roses in China and the Far East in 1867. They typically are very fragrant, bloom heavily in spring (though some repeat bloom) and are most often found in shades ranging from white and pale pink to burgundy. Also known as “Heirloom” or “Antique Roses,” the following classes of roses are within this grouping: Alba Roses The Albas and their hybrids are known as the “White Roses” of Shakespeare, though their blossoms range in color from pure white to shades of pink. They are vigorous, hardy and very disease resistant. Their sprays of blooms are fragrant and occur only once in a massive spring display. Many carry large red hips through the winter. Bluish foliage and upright growth habit make them a fine backdrop for other roses. They are to take some shade in the garden. Centifolias The Centifolias were made famous by the Dutch painters of the 17th century. Referred to as the “hundred-petaled” roses, or Cabbage Roses, they are one-time bloomers noted for the fullness and size of their flowers. Normally tall shrubs with arching growth, several are compact with smaller blossoms. All are very hardy. Damasks Hybrids of Rosa damascene, these are among the most ancient of garden roses. Cultivated by the Romans, they might have died out in medieval times had it not been for the European monasteries that grew roses for medical purposes. They are known for their Old Rose fragrance and the June flowering which produces an abundance of blooms sufficient for making large quantities of potpourri. -

Development and Difference in Germanic Colour Semantics

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264981573 Two kinds of pink: development and difference in Germanic colour semantics ARTICLE in LANGUAGE SCIENCES · AUGUST 2014 Impact Factor: 0.44 · DOI: 10.1016/j.langsci.2014.07.007 CITATIONS READS 3 87 8 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Cornelia van Scherpenberg Þórhalla Guðmundsdóttir Beck Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Mun… University of Iceland 3 PUBLICATIONS 4 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Linnaea Stockall Matthew Whelpton Queen Mary, University of London University of Iceland 18 PUBLICATIONS 137 CITATIONS 13 PUBLICATIONS 29 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Linnaea Stockall Retrieved on: 03 March 2016 Language Sciences xxx (2014) 1–16 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Language Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/langsci Two kinds of pink: development and difference in Germanic colour semantics Susanne Vejdemo a,*, Carsten Levisen b, Cornelia van Scherpenberg c, þórhalla Guðmundsdóttir Beck d, Åshild Næss e, Martina Zimmermann f, Linnaea Stockall g, Matthew Whelpton h a Stockholm University, Department of Linguistics, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden b Linguistics and Semiotics, Department of Aesthetics and Communication, Aarhus University, Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2, Bygning 1485-335, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark c Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 München, Germany d University of Iceland, Háskóli Íslands, Sæmundargötu 2, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland -

The Basic Colour Terms of Finnish1

Mari Uusküla The Basic Colour Terms of Finnish1 Abstract This article describes a study of Finnish colour terms the aim of which was to establish an inventory of basic colour terms, and to compare the results to the list of basic terms suggested by Mauno Koski (1983). Basic colour term in this study is understood as Brent Berlin and Paul Kay defined it in 1969. The data for the study was collected using the field method of Ian Davies and Greville Corbett (1994). Sixty-eight native speakers of Finnish, aged 10 to 75, performed two tasks: a colour-term list task (name as many colours as you know) and a colour naming task (where the subjects were asked to name 65 representative colour tiles). The list task was complemented by the cognitive salience index designed by Sutrop (2001). An analysis of the results shows that there are 10 basic colour terms in Finnish—punainen ‘red,’ sininen ‘blue,’ vihreä ‘green,’ keltainen ‘yellow,’ musta ‘black,’ valkoinen ‘white,’ oranssi ‘orange,’ ruskea ‘brown,’ harmaa ‘grey,’ and vaaleanpunainen ‘pink’. These results contrast with Mauno Koski’s claim that there are only 8 basic colour terms in Finnish. However, both studies agree that Finnish does not possess a basic colour term for purple. 1. Introduction Basic colour terms are a relatively well studied area of vocabulary and studies on them cover many languages of the world. Research on colour terms became particularly intense after the publication of Berlin and Kay’s (1969) inspiring and much debated monograph. Berlin and Kay argued that basic colour terms in all languages are drawn from a universal inventory of just 11 colour categories (see Figure 1). -

Berlin and Kay Theory

Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27851-8_62-2 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Berlin and Kay Theory C.L. Hardin* Department of Philosophy, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA Definition The Berlin-Kay theory of basic color terms maintains that the world’s languages share all or part of a common stock of color concepts and that terms for these concepts evolve in a constrained order. Basic Color Terms In 1969 Brent Berlin and Paul Kay advanced a theory of cross-cultural color concepts centered on the notion of a basic color term [1]. A basic color term (BCT) is a color word that is applicable to a wide class of objects (unlike blonde), is monolexemic (unlike light blue), and is reliably used by most native speakers (unlike chartreuse). The languages of modern industrial societies have thousands of color words, but only a very slender stock of basic color terms. English has 11: red, yellow, green, blue, black, white, gray, orange, brown, pink, and purple. Slavic languages have 12, with separate basic terms for light blue and dark blue. In unwritten and tribal languages the number of BCTs can be substantially smaller, perhaps as few as two or three, with denotations that span much larger regions of color space than the BCT denotations of major modern languages. Furthermore, reconstructions of the earlier vocabularies of modern languages show that they gain BCTs over time. These typically begin as terms referring to a narrow range of objects and properties, many of them noncolor properties, such as succulence, and gradually take on a more general and abstract meaning, with a pure color sense. -

Color Naming Experiment in Mongolian Language

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 4 No. 6; November 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Color Naming Experiment in Mongolian Language Nandin-Erdene Osorjamaa (Corresponding author) The National University of Mongolia, Orkhon school, Department of Translation Studies, Mongolia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Nansalmaa Nyamjav School of Science, Faculty of Humanities, Department of European Studies The National University of Mongolia, Mongolia E-mail: [email protected] Received: 20-03- 2015 Accepted: 21-06- 2015 Advance Access Published: August 2015 Published: 01-11- 2015 doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.6p.58 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.6p.58 Abstract There are numerous researches on color terms and names in many languages. In Mongolian language there are few doctoral theses on color naming. Cross cultural studies of color naming have demonstrated Semantic relevance in French and Mongolian color name Gerlee Sh. (2000); Comparisons of color naming across English and Mongolian Uranchimeg B. (2004); Semantic comparison between Russian and Mongolian idioms Enhdelger O. (1996); across symbolism Dulam S. (2007) and few others. Also a few articles on color naming by some Mongolian scholars are Tsevel, Ya. (1947), Baldan, L. (1979), Bazarragchaa, M. (1997) and others. Color naming studies are not sufficiently studied in Modern Mongolian. Our research is considered to be the first intended research on color naming in Modern Mongolian, because it is one part of Ph.D dissertation on color naming. There are two color naming categories in Mongolian, basic color terms and non- basic color terms. -

Kay (?) Color Naming Across Languages

2. Color Naming Across Languages Paul Kay, Brent Berlin, Luisa Maffi and William Merrifield 1. Introduction: Prior cross-linguistic research on color naming This chapter summarizes some of the research on cross-linguistic color categorization and naming that has addressed issues raised in Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution (Berlin and Kay 1969, hereafter B&K). It then advances some speculations regarding future developments—especially regarding the analysis, now in progress, of the data of the World Color Survey (hereafter WCS). In the latter respect the chapter serves as something of a progress report on the current state of analysis of the WCS data, as well as a promissory note on the full analysis to come. B&K proposed two general hypotheses about basic color terms and the categories they name: (1) there is a restricted universal inventory of such categories; (2) a language adds basic color terms in a constrained order, interpreted as an evolutionary sequence. These two hypotheses have been substantially confirmed by subsequent research.1 There have been changes in the more detailed formulation of the hypotheses, as well as additional empirical findings and theoretical interpretations since 1969. Rosch’s experimental work on Dani color (Heider 1972a, 1972b), supplemented by personal communications from anthropologists and linguists, showed that two-term systems contain, not terms for dark and light shades regardless of hue—as B&K had inferred—but rather one term covering white, red and yellow and one term covering black, green and blue, that is, a category of white plus ‘warm’ colors versus one of black plus ‘cool’ colors. -

Color Term Comprehension and the Perception of Focal Color in Young Children

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1973 Color term comprehension and the perception of focal color in young children. Charles G. Verge University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Verge, Charles G., "Color term comprehension and the perception of focal color in young children." (1973). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2050. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2050 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLOR TERM COMPREHENSION AND THE PERCEPTION OF FOCAL COLOR IN YOUNG CHILDREN A thesis presented By CHARLES G. VERGE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE March 1973 Psychology COLOR TERI^ COMPREHENSION AND THE PERCEPTION OF FOCAL COLOR IN YOUNG CHILDREN A Thesis By CHARLES G. VERGE Approved as to style and content by: March 1973 ABSTRACT Thirty 2-year-old subjects participated in a color per- ception task designed to assess the :i.nfluence of color term comprehension on the perception of "focal" color areas. The subject's task was to choose a color from an array of Munsell color chips consisting of one focal color chip with a series of non focal color chips. Eacn subject was given a color com- prehension and color naming task.