The Parable of the Boxer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

The Boxer Rising : a History of the Boxer Trouble in China

(Qurnell Uniuersity ffiibtary 3tl?ara, UStm fork CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Cornell University Library DS 771.S52 The Boxer rising :a history of the Boxer 3 1924 023 150 737 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023150737 THE BOXER RISING: A History of the Boxer Trouble In China. Reprinted from the "Shanghai Mercury." SECOMB EDITION. r er-v9Qg€L' '» Printed at the Shanghai Meeodry; Lid. % fa IV 1 i i AUGUST, 1901. ,,;|) s & \s| \t5o Sk*»<lk«^ >U^«-^| CONTENTS. Preface to First Edition i do. Second Edition .. viii History of the Boxer Movement 1 The Beginning of the Outbreak ... 17 The Scene of Strife 29 Eye-Witness's Narrative 31 Story of the Taku Forts Bombardment 33 The Ladies and Children at Taku ... 37 Adventures of Tongshan Refugees 38 The Disturbance in East Shantung ... 41 The Siege of Tientsin 43 Escape of the Shantung Missionaries 48 News from Chefoo 53 Affairs in Wenchow 55 Native Account of the Situation ... 58 The Situation'at Chefoo 65 The Murders at Kuchau ... 67 News from the Yangtze 69 The Situation in Szechuan 71 Wenchow Affairs ... 73 The Fighting at Newchwang 75 A Native's Experiences in Peking 80 KlATING 83 The Trouble at Amoy ; , 85 Shansi Missionaries 87 The Position at Tientsin 89 Tientsin and Peking . 91 Tientsin Notes 95 The Siege of Peking 98 The'Taking;and Occupation of Peking 113 Plan of Peking 116 The Cathedral Siege. -

Approved Electronically Generated Thesis/Dissertation Cover-Page

THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER - APPROVED ELECTRONICALLY GENERATED THESIS/DISSERTATION COVER-PAGE Electronic identifier: 14183 Date of electronic submission: 05/01/2015 The University of Manchester makes unrestricted examined electronic theses and dissertations freely available for download and reading online via Manchester eScholar at http://www.manchester.ac.uk/escholar. This print version of my thesis/dissertation is a TRUE and ACCURATE REPRESENTATION of the electronic version submitted to the University of Manchester's institutional repository, Manchester eScholar. Approved electronically generated cover-page version 1.0 Fighting for Change: Narrative accounts on the appeal and desistance potential of boxing A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 Deborah Louise Jump School of Law Contents Diagrams list……………………………………………………………………….. 8 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 9 Declaration…………………………………………………………………………. 10 Copyright Statement……………………………………………………………….. 10 Dedication………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………….... 11 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………….. 12 1.1. Origins of Thesis…………………………………………………………….. 12 1.2. Why Boxing?………………………………………………………………... 13 1.3. The Boxing Gym and Site of This Research……………………………....... 14 1.4. Boxing: What’s the Appeal?............................................................................ 15 1.5. Boxing and its Relationship to Desistance from Crime……………………... 16 1.6. -

The Red Mist

Based on the GUMSHOE One-2-One system by Robin D. Laws THE RED MIST BY Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan 1 THE RED MIST THE RED MIST A CTHULHU CONFIDENTIAL ADVENTURE by Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan Based on the GUMSHOE One-2-One system by Robin D. Laws TABLE OF CONTENTS THE RED MIST 4 THE BOXER 13 PHYLLIS OAKLEY 4 Talking to Drummer 13 SOURCES 4 James Chin 14 Helena Rogers, City Clerk 4 NO-WIN SITUATION 14 Erik Zackarov, Forger 4 McRory’s Speech 15 Mr. Wyilter, Irregular Customer 4 Screaming on the Inside 15 Dr. Maria Forrest, Old College Friend 5 OLD WOUNDS 15 David Shea, Reporter 5 SANITY CHECK 16 CHARACTER CARD 5 Wyilter’s Fears 16 RELATIONSHIP MAP 6 THE DEFEATED 17 SCENE FLOW DIAGRAM 6 Alvin & Dr. Lake 17 CAST 7 Alvin & Drummer 18 WHAT HAPPENED 7 Alvin & The Book 18 SCENES 8 FORMLESS SPAWN 18 A BEATEN MAN 8 MAKING THE DEAL 20 The Beaten Man 8 At Lake’s House 20 Talking To Drummer 8 INTO THE UNDERWORLD 20 Physical Evidence 9 Getting In 21 Drummer Leaves 9 The Fight Begins 22 Incipent Dreams 9 THE RED MIST 22 THE CLIENT 9 On An Advance 23 The Red Book 10 On A Hold 24 The Library Copy 10 On A Setback 24 Visiting Dr. Lake 11 Aftermath 24 The House 11 ANTAGONIST REACTIONS 25 Speaking to Lake 12 THE RED MIST PROBLEM CARDS 26 Obtaining the Book 13 THE RED MIST EDGE CARDS 28 CHARACTER CARD PHYLLIS OAKLEY 30 2 THE RED MIST THE RED MIST A boxer lost in a psychic labyrinth, a monster player what happened to her? Was it an accident? that lurks within our own minds, and a mysterious Unchecked bibliomania? A lost love? An encounter book combine to drag the investigator into a bloody with the supernatural? nightmare. -

The Structure of Meaning in the Boxing Film Genre Author(S): Leger Grindon Source: Cinema Journal, Vol

Society for Cinema & Media Studies Body and Soul: The Structure of Meaning in the Boxing Film Genre Author(s): Leger Grindon Source: Cinema Journal, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Summer, 1996), pp. 54-69 Published by: University of Texas Press on behalf of the Society for Cinema & Media Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1225717 Accessed: 10-12-2016 07:09 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Society for Cinema & Media Studies, University of Texas Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cinema Journal This content downloaded from 129.100.58.76 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 07:09:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Body and Soul: The Structure of Meaning in the Boxing Film Genre by Leger Grindon This essay focuses on the master plots, characterizations, settings, and genre his- tory of boxing in Hollywood fiction films since 1930. The boxer and boxing are significant figures in the Hollywood cinema, with ap- pearances in well over 150 feature-length fiction productions since 1930.1 During the decade 1975 to 1985 the screen boxer was prominent with, on the one hand, the enormous commercial success of the Rocky series and, on the other, the criti- cal esteem garnered by Raging Bull (1980). -

Joan Baez Birthday Celebration

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Mary Moyer, Sacks & Co. (for Joan Baez) 212-741-1000 or [email protected] . Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS Star-Studded Joan Baez 75 th Birthday Celebration Coming to THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in June on PBS David Bromberg, Jackson Browne, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Judy Collins, David Crosby, Emmylou Harris, Indigo Girls, Damien Rice, Paul Simon, Mavis Staples, Nano Stern, & Richard Thompson join Baez in duet Recorded live at New York’s historic Beacon Theatre, the program premieres on THIRTEEN Friday, May 6 at 9 p.m. Joan Baez celebrated her 75th birthday on Saturday, January 27 at New York’s historic Beacon Theatre. The special event honored her legendary 50 plus years in music with an intimate, career-spanning live performance. Baez performed alongside a remarkable array of superstar artists including: David Bromberg, Jackson Browne, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Judy 2 Collins, David Crosby, Emmylou Harris, Indigo Girls, Damien Rice, Paul Simon, Mavis Staples, Nano Stern, and Richard Thompson . The special Joan Baez 75 th Birthday Celebration will premiere on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in New York on Friday, May 6 at 9 p.m. before expanding nationwide to PBS stations in June. (Check local listings.) Prior to the gala celebratory event, Mary Chapin Carpenter had observed, "She has been a mentor, an inspiration and a role model for anyone who ever picked up a guitar and wanted to believe they could do more than just sing pretty songs. -

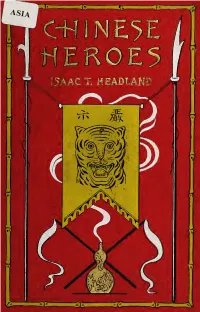

Chinese Heroes : Being a Record of Persecutions Endured by Native

MEADLAM, A ) J)S772- Hf3 Stltara. N»ni fork CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Cornell University Library DS 772.H43 Chinese heroes :being a record of persec 3 1924 023 151 107 The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023151107 CHINESE HEROES BEING A RECORD OF PERSECUTIONS ENDURED BY NATIVE CHRISTIANS IN THE BOXER UPRISING BY ISAAC TAYLOR HEADLAND Author of ^* Chinese Mother Goose Rhymes," *^ The Chinese Boy and Girl,*^ etc. WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS NEW YORK : EATON & MAINS CINCINNATI : JENNINGS & PYE Copyright by EATON & MAINS. 1902. Y 305- iT PREFACE MUCH has been written of the sufferings of foreigners in the recent Boxer uprising and correspondingly Httle of the conduct of the Chinese Christians. At a recent meeting of the North China Conference of the Methodist Epis- copal Church it was decided to inquire minutely into the persecutions from the standpoint of the natives, in the belief that a more adequate un- derstanding of their heroism would be a stimu- lant to the faith of the Church. A committee was therefore appointed, and the native pastors were requested to gather up and forward reports of such cases as might be considered representative of the persecutions as a whole. To these reports were added such in- cidents in the lives of certain of the members as would contribute to a proper estimate of their character, and thus enable the reader to see the persecutions in their proper settings. -

Mmylou Harris, Que Ses Intimes Appellent Emmy, Née Le 2 Avril 1947 À Birmingham En Alabama, Est Une Chanteuse Et Musicienne Américaine De Country Et De Country Rock

Birmingham http://www.emmylouharris.com/ WRCF: http://www.radiocountryfamily.info/crbst_330.html mmylou Harris, que ses intimes appellent Emmy, née le 2 avril 1947 à Birmingham en Alabama, est une chanteuse et musicienne américaine de country et de country rock. Elle est reconnue pour ses E interprétations d'œuvres de multiples compositeurs et pour son travail en tant qu'auteur- compositeur-interprète. Riche et variée, la carrière d'Emmylou Harris s'étend sur plus de quatre décennies. Entre tradition et modernité, la chanteuse a transcendé les styles, marquant de son talent le folk, la country, la country-rock, le bluegrass, le Western Swing et le mouvement Americana. Fille de Walter Rutland Harris un militaire de carrière (US Air Force) et d’Eugenia Murchison, Emmylou Harris, après de fréquents déménagements liés à la carrière de son père, grandit ainsi entre la Caroline, mais aussi la Virginie et devient très vite indépendante. Elle apprend très tôt la guitare, instrument prêté par un cousin. Quelques temps après, son grand-père, voyant la passion de sa petite fille pour la musique, lui offre une guitare ‘’Kay’’. Elle commence dès l'âge de 17 ans une ‘’carrière’’ de chanteuse dans les clubs et les ‘’coffee house’’ où elle sera aussi serveuse et participe ainsi à la fin du mouvement folk de la Côte Est. Ses artistes référents sont : Bob Dylan et Joan Baez. 1968, Emmylou entre à l'université de Caroline du Nord, pour étudier l'art dramatique, avec comme projet de devenir actrice. Après une année et demie, elle change d’université pour rejoindre celle de Virginia Beach près de Norfolk et finit par abandonner ses études. -

THE FOLK CLUB of RESTON-HERNDON Saved a Bundle! Join up on Folk Club Tuesdays, Or Call a Meets Tuesday Nights, 7:30Pm at the Tortilla Factory Board Member for Info

TTHHEE FFOOLLKK CCLLUUBB OOFF RREESSTTOONN——HHEERRNNDDOONN Preserving the traditions of Volume 21, Issue 2 Folk Music, Folklore, and Gentle Folk Ways February 2005 Mardi Gras February 8 Showcase – The All-New Genetically Altered Jug Band By Dan Grove “The All New Genetically Altered Jug Band (ANGAJB) provides a fun time for all ages by playing music that makes you smile! Featuring novelty songs of the 20th Century, the band performs both obscure oldies and lively original tunes.” That’s how these guys describe themselves on their website, but it doesn’t begin to capture the animated zaniness that is ANGAJB’s forte. Imagine banjo, kazoo, washtub bass, trumpet, whistles, tintinnabulating clankety percussion, and vocals all colliding in a highly caffeinated pileup, asking “Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavor on the Bedpost Overnight?” These guys won’t just make you smile, they’ll have slack- jawed astonishment competing with laugh-out-loud hilarity in a death-match competition for control of your face. Your cheeks will be sore for weeks! So, who are these guys? The most familiar one to Folk Clubbers is Ron Goad, the Club’s MVP percussionist. In ANGAJB you’ll see him putting on thimbles to play a washboard/tin can/bike horn/wood block/junkyard thing of beauty created by Harny (Ken Harnage). The man is made of mischief, and with this weaponized washboard he’s downright dangerous. Famously born in an elevator (cue the theme from Shaft), Ron performs and records prolifically, and is a board member of Focus (www.focusmusic.org) and the Songwriters’ Association of Washington (saw.org). -

Bodies in Play: Female Athleticism in Nineteenth-Century Literature

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Bodies In Play: Female Athleticism In Nineteenth- Century Literature Jillian Weber University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Weber, J.(2018). Bodies In Play: Female Athleticism In Nineteenth-Century Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4786 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BODIES IN PLAY: FEMALE ATHLETICISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY LITERATURE by Jillian Weber Bachelor of Arts University of Illinois, 2009 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Leon Jackson, Major Professor Catherine Keyser, Major Professor Cynthia Davis, Committee Member Katherine Adams, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Jillian Weber, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the University of South Carolina, the Institute for African American Research, and the Bilinski Educational Foundation for generously funding me through a Presidential Fellowship, a SPARC grant, an IAAR fellowship, and a Bilisnki Fellowship. This funding made it possible to complete my research and finish my dissertation. Without the generosity, patience, advice, and guidance, of Cat Keyser, Leon Jackson, Cynthia Davis, and Kate Adams, this dissertation would have never come to fruition. -

Ethan Johns Selected Producer, Mixer & Musician Credits

ETHAN JOHNS SELECTED PRODUCER, MIXER & MUSICIAN CREDITS: Allison Pierce The Year of The Rabbit (Sony Masterworks) P E Mu A Seth Lakeman ft. Wildwood Kin Ballads Of The Broken Few (Cooking Vinyl) P co-M I'm With Her Forthcoming Album (TBD) P White Denim Stiff (Downtown) P M Boy & Bear Limit of Love (Nettwerk) P M Tom Jones Long Lost Suitcase (Virgin) P M Mu Ethan Johns with The Black Eyed Dogs Silver Liner (Three Crows/Caroline International) Mu W Paul McCartney New (MPL/Concord) P Mu Laura Marling Once I Was An Eagle (EMI) P E M Mu Ethan Johns If Not Now Then When (Three Crows) P E Mu W The Vaccines The Vaccines Come of Age (Columbia) P Tom Jones Spirit In The Room (Island UK) P M The Staves Dead & Born & Grown (Warner) co-P co-M The Staves The Motherlode: EP (Warner) co-P co-M Kaiser Chiefs Future Is Medieval (Fiction/B-Unique) P E M Priscilla Ahn When You Grow Up (Blue Note) P E M Mu Michael Kiwanuka "I'll Get Along" and "I Won't Lie" from Home Again P E M (Deluxe Version) (Polydor) The Boxer Rebellion The Cold Still (Absentee) P E M Red Cortez Forthcoming Album P E M Tom Jones Praise And Blame (Island UK) P E M The London Souls The London Souls (Soul On 10/DD172) P E M Laura Marling A Creature I Don't Know (EMI) P E M Laura Marling I Speak Because I Can (EMI) P E M Paolo Nutini Sunny Side Up (Atlantic UK) P E M Ray LaMontagne Gossip in the Grain (RCA) P E M Mu Grammy Nomination - Best Engineered Album 2009 Ray LaMontagne Till the Sun Turns Black (RCA) P E M Ray LaMontagne Trouble (RCA) P E M Turin Brakes Dark On Fire (EMI) P E M Joe -

Newcastleýpniverisity Licrary' ---204

What is your value? A qualitative study into the development of capital in amateur and professional boxing JOHN ANTHONY FULTON NEWCASTLEýPNIVERISITY LICRARY' )ý0444 --------- ------------------- 204 , 9 2oø A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne for the degree of Doctor of Education. Page Acknowledgments To the memory of my mother andfather Helen Callander Fulton and John Francis Fulton Special thanks to: My acaden-dcsupervisor ProfessorJames Tooley for excellent guidance. ShelaghKeogh, whose help and support went well beyond the call of duty. ProfessorMelanie jasper and Christine Keogh who conunented on an earlier draft of the work. David Ashdown, Clive Gibson and GraemeLittlewood for all their help and encouragement. All the boxers who helped me and freely gave of their time during this researchprocess. Page3 TA 71 .. I v Yflul. LIO LIU"[ VULUC: . A qualitative study into the developmentof capital in amateur and professional boxing Abstract This study is an investigation into ways in which participating in and learning within the context of sport, and amateur and professional boxing in particular, impacts on the lives of the participants. More specifically, the aim of this study is to explore ways in which body capital can lead to the development of other types of capital. The study focused on the experienceof professional and amateur boxers. 18 people involved in boxing were interviewed and these interviews were combined with approximately 1000 hours of participant observation in boxing settings. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and detailed field notes recorded the observations.The data was analysed and categoriesand themes emerged from this data analysis.