APPENDIX 6.5 Cultural Resource Documentation Historic Resources Report DRAFT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

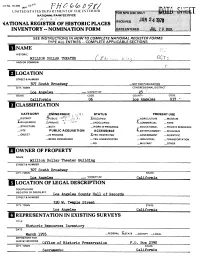

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Hclassifi Cation

No. 10-300 ^,.^ P^ ^% (& f) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC MILLION DOLLAR THEATER AND/OR COMMON " LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 307 South Broadway _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 25 "'. Los Angeles —.VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Cali fornia 06 Los Angeles 037 *" HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY -OWNERSHIP v , , "/ STATUS PRESENT USE X fpcK i> -. —DISTRICT ^PUBLIC C1 ^ 0; f 5; J(,f -X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM i-BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE "f • ^^':ff- —UNOCCUPIED ^-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^.ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS iYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Million Dollar Theater Building STREET & NUMBER _____307 South Broadway CITY, TOWN STATE Los Angeles VICINITY OF California LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Los Angeles County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 W. Temple Street CITY, TOWN STATE Los Angeles California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Resources Inventory DATE March 1976 —FEDERAL X.STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qff±c& pf Historic PreserYation P.O. Box 2390 CITY, TOWN STATE Sacramento California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X-GOOD —RUINS ^.ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The structure consists of two major units; a twelve-story, steel-frame office building of concrete and brick, and a reinforced-concrete theater building faced with brick and terra cotta. -

Download the PDF Here

Rancho map of Ventura County, showing (inset) Public Land between Rancho Guadalasca to the west and the Ventura/Los Angeles County line on the east, the subject of this issue of the Journal. Published by TICOR Title Insurance Co. in 1988, Leavitt Dudley, artist. — Cover — Yerba Buena and beyond: looking east from Deer Creek Road to Malibu, 2012. Courtesy John Keefe “The Big Ranch Fight” — Table of Contents — Introduction by Charles N. Johnson page 4 “The Big Ranch Fight” by Jo Hindman page 13 About the Author page 33 Afterword by Linda Valois page 35 Appendix page 38 Acknowledgments page 39 Epilogue page 44 VOLUME 53 NUMBER 2 © 2011 Ventura County Historical Society; Museum of Ventura County. All rights reserved. All images, unless indicated otherwise, are from the Museum Research Library Collections. The Journal of Ventura County History 1 Section, Marblehead Land Company Map, 1924, showing location of Houston property (section 15 upper left). Yerba Buena School House (section 11) and entrance to Yerba Buena Road (section 27). Courtesy Mario Quiros 2 “The Big Ranch Fight” “We too are anxious to see those lands settled and improved. It would be far better for us and for everybody else if these disputes had been settled long ago.” Jerome Madden Head of the Southern Pacific Railroad Land Department Ventura Free Press, January 26, 1900 “My mother who had come from Canada to California to be married, had been raised on a farm in a level country. She always referred to this hill as ‘the Mountain.’ There was no road to it, so she had to go up or come down on horseback…. -

LACEA Alive Feb05 7.Qxd

01-68_Alive_JAN09_v7.qxd 12/26/08 3:21 PM Page 22 22 January 2009 City Employees Club of Los Angeles, Alive! A City of [ PART 1 OF 2 ] Theatres By Marc Wanamaker n Noted theatre historian Marc Wanamaker is Hynda’s guest columnist this month. Part two continues next month. t is not generally known, but Los Angeles was one of the largest Itheatre towns in the United States dating back to the 19th cen- tury. Beginning with legitimate stages and later cinema theatres, Los Angeles boasted more than several thousand theatres sprawl- ing throughout the entire Los Angeles area by the 1920s. Every main street in every town had a theatre on it, and by the time movies came to Los Angeles there were even more built that were bigger and better. Los Angeles had a grand legitimate theatre history since the mid-19th century as described by famed stage and film actor Hobart Bosworth, who worked in several of the downtown theatres in the 1880s and 1890s. Bosworth described the theatre world of Los Angeles as “surprisingly robust and patronized by thousands of residents who were knowledgeable about the plays and players.” Los Angeles had its first semi-permanent stage, an open-air cov- ered platform with a proscenium arch near the Plaza in 1848, but the most important theater to be built in Los Angeles was the 1,200-seat Ozro Childs Grand Opera House, built in 1884 on Main Street near First. From the mid-1880s, Los Angeles became a regular stop for touring theatrical companies, starring some of the world’s most illustrious stars including Sarah Bernhardt, Maurice Barrymore, Lillian Russell, Anna Held and Lionel Barrymore, among many others. -

Watershed Summaries

Appendix A: Watershed Summaries Preface California’s watersheds supply water for drinking, recreation, industry, and farming and at the same time provide critical habitat for a wide variety of animal species. Conceptually, a watershed is any sloping surface that sheds water, such as a creek, lake, slough or estuary. In southern California, rapid population growth in watersheds has led to increased conflict between human users of natural resources, dramatic loss of native diversity, and a general decline in the health of ecosystems. California ranks second in the country in the number of listed endangered and threatened aquatic species. This Appendix is a “working” database that can be supplemented in the future. It provides a brief overview of information on the major hydrological units of the South Coast, and draws from the following primary sources: • The California Rivers Assessment (CARA) database (http://www.ice.ucdavis.edu/newcara) provides information on large-scale watershed and river basin statistics; • Information on the creeks and watersheds for the ESU of the endangered southern steelhead trout from the National Marine Fisheries Service (http://swr.ucsd.edu/hcd/SoCalDistrib.htm); • Watershed Plans from the Regional Water Quality Control Boards (RWQCB) that provide summaries of existing hydrological units for each subregion of the south coast (http://www.swrcb.ca.gov/rwqcbs/index.html); • General information on the ecology of the rivers and watersheds of the south coast described in California’s Rivers and Streams: Working -

To Oral History

100 E. Main St. [email protected] Ventura, CA 93001 (805) 653-0323 x 320 QUARTERLY JOURNAL SUBJECT INDEX About the Index The index to Quarterly subjects represents journals published from 1955 to 2000. Fully capitalized access terms are from Library of Congress Subject Headings. For further information, contact the Librarian. Subject to availability, some back issues of the Quarterly may be ordered by contacting the Museum Store: 805-653-0323 x 316. A AB 218 (Assembly Bill 218), 17/3:1-29, 21 ill.; 30/4:8 AB 442 (Assembly Bill 442), 17/1:2-15 Abadie, (Señor) Domingo, 1/4:3, 8n3; 17/2:ABA Abadie, William, 17/2:ABA Abbott, Perry, 8/2:23 Abella, (Fray) Ramon, 22/2:7 Ablett, Charles E., 10/3:4; 25/1:5 Absco see RAILROADS, Stations Abplanalp, Edward "Ed," 4/2:17; 23/4:49 ill. Abraham, J., 23/4:13 Abu, 10/1:21-23, 24; 26/2:21 Adams, (rented from Juan Camarillo, 1911), 14/1:48 Adams, (Dr.), 4/3:17, 19 Adams, Alpha, 4/1:12, 13 ph. Adams, Asa, 21/3:49; 21/4:2 map Adams, (Mrs.) Asa (Siren), 21/3:49 Adams Canyon, 1/3:16, 5/3:11, 18-20; 17/2:ADA Adams, Eber, 21/3:49 Adams, (Mrs.) Eber (Freelove), 21/3:49 Adams, George F., 9/4:13, 14 Adams, J. H., 4/3:9, 11 Adams, Joachim, 26/1:13 Adams, (Mrs.) Mable Langevin, 14/1:1, 4 ph., 5 Adams, Olen, 29/3:25 Adams, W. G., 22/3:24 Adams, (Mrs.) W. -

L Ss Tio Is T Ti

L SS TIO IS T TI Groundwater Basin Adjudication c/o JND Legal Administration P.O. Box 91244 Seattle, WA 98111 1-833-291-1643 Hello, Enclosed is the Notice of Commencement of Groundwater Basin Adjudication, Answer to Adjudication Complaint, and Second Amended Verified Complaint, which pertain to a lawsuit concerning the Las Posas Valley Groundwater Basin. This case (Case No. VENCI00509700) is currently being heard in the Santa Barbara County Superior Court, Civil Division, Department No. 3, 1100 Anacapa St, Santa Barbara, California 93121. If you have any questions concerning the Groundwater Basin Adjudication, please call I-833-291-1643, or write to Groundwater Basin Adjudication, c/o JND Legal Administration, P.O. Box 91244, Seattle, WA 98111. Administrator Enclosures: Notice of Commencement of Groundwater Basin Adjudication, Answer to Adjudication Complaint, and Second Amended Verified Complaint 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA 9 COUNTY OF SANTA BARBARA 10 LAS POSAS VALLEY WATER RIGHTS CASE NO. VENCI00509700 COALITION, an unincorporated association; 11 PLACCO, INC., a California Corporation; Assignedfor all purposes to the Honorable GRIMES ROCK, INC., a California Thomas P. Anderle 12 corporation; SATICOY PROPERTIES, LLC, a California limited liability company; SCS ANSWER TO ADJUDICATION 13 PARTNERS, a California partnership; GREEN COMPLAINT HILLS RANCH, LLC, a California limited 14 liability company; ROLLING GREEN HILLS RANCH, LLC, a California limited liability 15 company, 16 Plaintiffs, 17 V. 18 FOX CANYON GROUNDWATER -

Final Program Environmental Impact Report Environmental Assessment for the Calleguas Regional Salinity Management Project

FINAL PROGRAM ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE CALLEGUAS REGIONAL SALINITY MANAGEMENT PROJECT SCH NO. 2000101104 EA no. 01-LC-007 Lead Agency: August 2002 FINAL PROGRAM ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE CALLEGUAS REGIONAL SALINITY MANAGEMENT PROJECT Prepared for: Calleguas Municipal Water District 2100 Olsen Road Thousand Oaks, California 91360 Prepared by: Padre Associates, Inc. 5450 Telegraph Road, Suite 101 Ventura, California 93003 805/644-2220, 805/644-2050 (fax) August 2002 Project No. 9902-1761 Calleguas Municipal Water District Calleguas Regional Salinity Management Project Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................1-1 1.1 DOCUMENT PURPOSE AND LEGAL AUTHORITY ............................................1-1 1.2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES/PURPOSE AND NEED ................................................1-3 1.3 SCOPE AND CONTENT .......................................................................................1-4 1.4 RESPONSIBLE AND TRUSTEE AGENCIES .......................................................1-6 1.5 MITIGATION MONITORING PLAN.......................................................................1-6 1.6 PROJECT APPROVALS AND PERMITS .............................................................1-7 1.7 CERTIFICATION OF THE FINAL PROGRAM EIR ...............................................1-7 2.0 SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................2-1 -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Map of the Santa Paula-Sespe Oil Fields, Including Bardsdale, South Mountain & Camarillo, Ventura County, California . Revised to July 9, 1932 Stock#: 53128 Map Maker: Cal. State Mining Bureau Dept. of Petroleum & Gas Date: 1920 Place: n.p. Color: Uncolored Condition: VG Size: 36 x 36 inches Price: SOLD Description: Highly detailed large format map of the Santa Paula-Sespe Oil Fields, in Ventura County,identifying both Oil related details and Ranchos in Ventura County. The map shows the Rancho Ex-Mission San Buenaventura, Seape Rancho, Rancho Simi, Rancho Las Posas, Rancho Santa Clara del Norte, Rancho Santa Paula y Saticoy, Rancho Calleguas, Rancho El Conejo and part of Rancho Guadalasca. Larger land owners including Union Oil Company, R.P. Strathearn, Ventura Oil Co., F.C. Fisher, USA, State of California, Echo Brea Oil Co., Berrywood Investment Co., Citrus Heights Development Co., Adolfo & Juan Camarillo, Conejo Oil Syndicate and many others. A key at the bottom identifies the following oil and gas related features: Rigs in Place, Rigs in Place abandoned, Uncompleted, Uncompleted and abandoned, Completed, Completed and Abandoned, Water, Drawer Ref: Rolled Maps Stock#: 53128 Page 1 of 2 Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Map of the Santa Paula-Sespe Oil Fields, Including Bardsdale, South Mountain & Camarillo, Ventura County, California . Revised to July 9, 1932 Water Abandoned, Gas, Gas Abandoned, Tanks and a Tunnel. -

Phase I Report

PHASE I REPORT June 2005 Calleguas Creek Watershed Integrated Regional Water Management Plan This Integrated Regional Water Management Plan (IRWMP) is comprised of two volumes: Volume I: Calleguas Creek Watershed Management Plan Phase I Report Volume II: Calleguas Creek Watershed Management Plan Addendum Volume I is provided as a separate document and Volume II is attached. Volume II is intended to bridge the gap between the Calleguas Creek Watershed Management Plan and the requirements for IRWMPs found in the Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM) Grant Program Guidelines (Guidelines). The two volumes, together, are intended to be a functionally- equivalent IRWMP document. The Guidelines were prepared by the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) and the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) in November 2004 to provide guidance on the process and criteria that DWR and SWRCB will use to evaluate grant applications under the IRWM Grant Program. The Grant program resulted from the passage of Proposition 50, the Water Security, Clean Drinking Water, Coastal and Beach Protection Act of 2002. IRWM is discussed in Chapter 8 of Proposition 50. p:\05\0587108_cmwd_irwmp\attachments\attach3_irwmp\camrosa_only_preface.doc PHASE I REPORT June 2005 Table of Contents Table of Contents........................................................................................................................... i List of Tables............................................................................................................................... -

Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, Circa 1852-1904

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb109nb422 Online items available Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Finding Aid written by Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Documents BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM 1 Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in Cali... Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt. Date Completed: March 2008 © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Documents pertaining to the adjudication of private land claims in California Date (inclusive): circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892 Microfilm: BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM Creators : United States. District Court (California) Extent: Number of containers: 857 Cases. 876 Portfolios. 6 volumes (linear feet: Approximately 75)Microfilm: 200 reels10 digital objects (1494 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: In 1851 the U.S. -

Stormwater Management

3.3 Stormwater Management 3.3 STORMWATER MANAGEMENT This section of the Technical Background Report describes the background, identifies general drainage patterns, existing and future conditions, and related issues in the planning area. The various sources used in the preparation of this chapter include county and local resources such as Ventura County Public Works Agency Watershed Protection District and City of Simi Valley. 3.3.1 Background The City of Simi Valley is located in the southeastern portion of Ventura County immediately adjacent to Los Angeles County. The developed portions of the City are situated primarily on the valley floor with proposed development extending up to the alluvial fans coming out of canyons. The valley is defined by the Santa Susana Mountains on the north and east and by the Simi Hills on the south. The Santa Susana Mountains separate the Simi Valley from the Santa Clara River Valley and Towns Fillmore and Piru to the north. The Simi Hills separate the valley from the City of Thousand Oaks to the southwest, and Moorpark Sphere of Influence separates the western limit.19 The major drainage course through the valley is the Arroyo Simi. The Arroyo Simi is approximately 11.7 miles in length. This major creek drains from the extreme limits of the watershed in the east and northeast, then westerly through the Las Posas Valley (As Arroyo Las Posas) to the Oxnard Plain (as Calleguas Creek) and the Pacific Ocean. Tributaries to Arroyo Simi from the Santa Susana Mountains on the north are (from west to east), Alamos Canyon, Brea Canyon, North Simi Drain, Dry Canyon, Tapo Canyon, Chivo Canyon, and Las Llajas Canyon.