Trees of the Carson National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Juniper Woodlands of the Pacific Northwest

Western Juniper Woodlands (of the Pacific Northwest) Science Assessment October 6, 1994 Lee E. Eddleman Professor, Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Patricia M. Miller Assistant Professor Courtesy Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Richard F. Miller Professor, Rangeland Resources Eastern Oregon Agricultural Research Center Burns, Oregon Patricia L. Dysart Graduate Research Assistant Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................... i WESTERN JUNIPER (Juniperus occidentalis Hook. ssp. occidentalis) WOODLANDS. ................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................ 1 Current Status.............................................. 2 Distribution of Western Juniper............................ 2 Holocene Changes in Western Juniper Woodlands ................. 4 Introduction ........................................... 4 Prehistoric Expansion of Juniper .......................... 4 Historic Expansion of Juniper ............................. 6 Conclusions .......................................... 9 Biology of Western Juniper.................................... 11 Physiological Ecology of Western Juniper and Associated Species ...................................... 17 Introduction ........................................... 17 Western Juniper — Patterns in Biomass Allocation............ 17 Western Juniper — Allocation Patterns of Carbon and -

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photograph taken by Richard F. Miller. Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions By R.F. Miller, Oregon State University, J.D. Bates, T.J. Svejcar, F.B. Pierson, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and L.E. Eddleman, Oregon State University This is contribution number 01 of the Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP), supported by funds from the U.S. Joint Fire Science Program. Partial support for this guide was provided by U.S. Geological Survey Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center. Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials con- tained within this report. Suggested citation: Miller, R.F., Bates, J.D., Svejcar, T.J., Pierson, F.B., and Eddleman, L.E., 2007, Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions: U.S. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

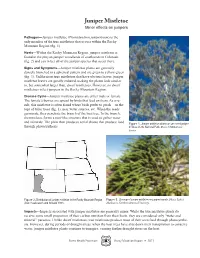

Juniper Mistletoe Minor Effects on Junipers

Juniper Mistletoe Minor effects on junipers Pathogen—Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is the only member of the true mistletoes that occurs within the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 1). Hosts—Within the Rocky Mountain Region, juniper mistletoe is found in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of southwestern Colorado (fig. 2) and can infect all of the juniper species that occur there. Signs and Symptoms—Juniper mistletoe plants are generally densely branched in a spherical pattern and are green to yellow-green (fig. 3). Unlike most true mistletoes that have obvious leaves, juniper mistletoe leaves are greatly reduced, making the plants look similar to, but somewhat larger than, dwarf mistletoes. However, no dwarf mistletoes infect junipers in the Rocky Mountain Region. Disease Cycle—Juniper mistletoe plants are either male or female. The female’s berries are spread by birds that feed on them. As a re- sult, this mistletoe is often found where birds prefer to perch—on the tops of taller trees (fig. 1), near water sources, etc. When the seeds germinate, they penetrate the branch of the host tree. In the branch, the mistletoe forms a root-like structure that is used to gather water and minerals. The plant then produces aerial shoots that produce food Figure 1. Juniper mistletoe plants on one-seed juniper through photosynthesis. in Mesa Verde National Park. Photo: USDA Forest Service. Figure 2. Distribution of juniper mistletoe in the Rocky Mountain Region Figure 3. Closeup of juniper mistletoe on juniper branch. Photo: Robert (from Hawksworth and Scharpf 1981). Mathiasen, Northern Arizona University. Impacts—Impacts associated with juniper mistletoe are generally minor. -

Wakefield 306 2Nd 79500 307 2Nd 71300

WAKEFIELD 306 2ND 79500 307 2ND 71300 405 2ND 56100 406 2ND 81000 409 2ND 8110 508 2ND 124000 302 3RD 83920 303 3RD 131700 304 3RD 112500 305 3RD 25000 306 3RD 139000 307 3RD 56700 308 3RD 58000 403 3RD 10870 405 3RD 35700 501 3RD 144200 503 3RD 17120 704 3RD 33780 804 3RD 920 902 3RD 47800 1600 3RD 15410 1706 3RD 22050 1708 3RD 113870 301 4TH 166700 303 4TH 46400 305 4TH 74900 306 4TH 130300 307 4TH 120300 402 4TH 121900 404 4TH 125800 602 4TH 78100 606 4TH 132500 701 4TH 174540 706 4TH 227000 305 5TH 20500 308 5TH 100970 312 5TH 150800 102 6TH 117950 104 6TH 57100 106 6TH 84360 204 6TH 89200 206 6TH 38200 208 6TH 73900 304 6TH 18490 305 6TH 77130 401 6TH 148000 403 6TH 31750 607 6TH 106500 701 6TH 162000 703 6TH 178500 705 6TH 173300 805 6TH 131900 102 7TH 145000 103 7TH 151500 104 7TH 186800 107 7TH 141500 201 7TH 121200 202 7TH 138300 203 7TH 168900 204 7TH 118800 206 7TH 125500 303 7TH 50600 404 7TH 18170 602 8TH 123100 802 8TH 98700 803 8TH 181400 804 8TH 104900 903 8TH 6080 905 8TH 6080 1001 8TH 6090 1003 8TH 183100 1005 8TH 176700 1007 8TH 167800 1101 8TH 225800 702 9TH 187200 704 9TH 240500 804 9TH 101600 603 10TH 10810 604 10TH 242900 706 10TH 44810 802 10TH 41110 901 10TH 130900 902 10TH 265000 902 10TH 13530 904 10TH 674320 905 10TH 80040 402 BIRCH 79800 403 BIRCH 148900 404 BIRCH 90000 405 BIRCH 107900 406 BIRCH 116100 502 BIRCH 200800 503 BIRCH 145500 504 BIRCH 63000 505 BIRCH 110600 506 BIRCH 216300 602 BIRCH 167600 603 BIRCH 160500 604 BIRCH 96000 605 BIRCH 151100 605 BIRCH 16180 606 BIRCH 6500 607 BIRCH 109300 608 BIRCH -

Balkan Vegetation

Plant Formations in the Balkan BioProvince Peter Martin Rhind Balkan Mixed Deciduous Forest These forests vary enormously but usually include a variety of oak species such as Quercus cerris, Q. frainetto, Q. robur and Q. sessiliflora, and other broadleaved species like Acer campestris, Carpinus betulus, Castanea sative, Juglans regia, Ostrya carpinifolia and Tilia tomentosa. Balkan Montane Forest Above about 1000 m beech Fagus sylvatica forests often predominate, but beyond 1500 m up to about 1800 m various conifer communities form the main forest types. However, in some cases conifer and beech communities merge and both reach the tree line. The most important associates of beech include Acer platanoides, Betula verrucosa, Corylus colurna, Picea abies, Pyrus aucuparia and Ulmus scabra, while the shrub layer often consists of Alnus viridis, Euonymous latifolius, Pinus montana and Ruscus hypoglossum. The ground layer is not usually well developed and many of the herbaceous species are of central European distribution including Arabis turrita, Asperula muscosa, Cardamine bulbifera, Limodorum abortivum, Orthilia seconda and Saxifraga rotundifolia. Of the conifer forests, Pinus nigra (black pine) often forms the dominant species particularly in Bulgaria, Serbia and in the Rhodope massif. Associated trees may include Taxus buccata and the endemic Abies bovisii-regis (Macedonian fir), while the shrub layer typically includes Daphne blagayana, Erica carnea and the endemic Bruckenthalia spiculifolia (Ericaceae). In some areas there is a conifer forest above the black pine zone from about 1300 m to 2400 m in which the endemic Pinus heldreichii (Bosnian pine) predominates. It is often rather open possibly as a consequence of repeated fires. -

The World Needs Network Innovation. Juniper Is Here to Help

The world needs network innovation. Juniper is here to help. In a world where the pace of change is accelerating at an unprecedented rate the network has taken on a new level of importance as the vehicle for pulling together our best people, best thinking, and best hope for addressing the critical challenges we face as a global community. The JUNIPER BY THE macro-trends of cloud computing and the mobile Internet NUMBERS hold the potential to expand the reach and power of the network—while creating an explosion of new subscribers, • The world’s top five social media properties new traffic, and new content. In the face of such intense are supported by Juniper demand, this potential cannot be realized with legacy Networks. thinking. Juniper Networks stands as a response and a • The top 10 telecom companies challenge to the traditional approach to the network. in the world run on Juniper Networks. • Juniper Networks is deployed in more than 1,400 national Our Vision government organizations We believe the network is the single greatest vehicle for knowledge, collaboration, and around the world. human advancement that the world has ever known. Now more than ever, the world relies on high-performance networks. And now more than ever, the world needs network • Juniper has over 8,700 innovation to unleash our full potential. employees in 46 worldwide offices, serving over 100 The network plays a central role in addressing the critical challenges we face as a global countries. community. Consider the healthcare industry, where the network is the foundation for new models of mobile affordable care for underserved communities. -

Description of the Ecoregions of the United States

(iii) ~ Agrl~:::~~;~":,c ullur. Description of the ~:::;. Ecoregions of the ==-'Number 1391 United States •• .~ • /..';;\:?;;.. \ United State. (;lAn) Department of Description of the .~ Agriculture Forest Ecoregions of the Service October United States 1980 Compiled by Robert G. Bailey Formerly Regional geographer, Intermountain Region; currently geographer, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Prepared in cooperation with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and originally published as an unnumbered publication by the Intermountain Region, USDA Forest Service, Ogden, Utah In April 1979, the Agency leaders of the Bureau of Land Manage ment, Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Geological Survey, and Soil Conservation Service endorsed the concept of a national classification system developed by the Resources Evaluation Tech niques Program at the Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, to be used for renewable resources evaluation. The classifica tion system consists of four components (vegetation, soil, landform, and water), a proposed procedure for integrating the components into ecological response units, and a programmed procedure for integrating the ecological response units into ecosystem associations. The classification system described here is the result of literature synthesis and limited field testing and evaluation. It presents one procedure for defining, describing, and displaying ecosystems with respect to geographical distribution. The system and others are undergoing rigorous evaluation to determine the most appropriate procedure for defining and describing ecosystem associations. Bailey, Robert G. 1980. Description of the ecoregions of the United States. U. S. Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publication No. 1391, 77 pp. This publication briefly describes and illustrates the Nation's ecosystem regions as shown in the 1976 map, "Ecoregions of the United States." A copy of this map, described in the Introduction, can be found between the last page and the back cover of this publication. -

Altitudinal and Polar Treelines in the Northern Hemisphere – Causes and Response to Climate Change

Umbruch 79 (3) 05.08.2010 23:45 Uhr Seite 139 Polarforschung 79 (3), 139 – 153, 2009 (erschienen 2010 Altitudinal and Polar Treelines in the Northern Hemisphere – Causes and Response to Climate Change by Friedrich-Karl Holtmeier1* and Gabriele Broll2 Abstract: This paper provides an overview on the main treeline-controlling dem Vorrücken der Baumgrenze in größere, wesentlich windigere Höhen factors and on the regional variety as well as on heterogeneity and response to relativ zunehmen. Die Verlagerung der Baumgrenze in größere Höhen und changing environmental conditions of both altitudinal and northern treelines. weiter nach Norden wird zu grundlegenden Veränderungen der Landschaft in From a global viewpoint, treeline position can be attributed to heat deficiency. den Hochgebirgen und am Rande von Subarktis/Arktis führen, die auch wirt- At smaller scales however, treeline position, spatial pattern and dynamics schaftliche Folgen haben werden. depend on multiple and often elusive interactions due to many natural factors and human impact. After the end of the Little Ice Age climate warming initiated tree establishment within the treeline ecotone and beyond the upper INTRODUCTION and northern tree limit. Tree establishment peaked from the 1920s to the 1940s and resumed again in the 1970s. Regional and local variations occur. In most areas, tree recruitment has been most successful in the treeline ecotone Global warming since the end of the “Little Ice Age” (about while new trees are still sporadic in the adjacent alpine or northern tundra. 1900) is bringing about socio-economic changes, shrinking Lack of local seed sources has often delayed tree advance to higher elevation. -

Identification of Recent Factors That Affect the Formation of the Upper Tree Line in Eastern Serbia

Arch. Biol. Sci., Belgrade, 63 (3), 825-830, 2011 DOI:10.2298/ABS1103825D IDENTIFICATION OF RECENT FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE FORMATION OF THE UPPER TREE LINE IN EASTERN SERBIA V. DUCIĆ1, B. MILOVANOVIĆ2 and S. ĐURĐIĆ1 1 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Geography, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijić”, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia Abstract - The recent climate changes, among others, have contributed to the change in elevation of the upper tree line in high mountainous areas. At the same time, direct anthropogenic impact on the fragile ecosystems of high mountains has also been significant. The aim of this paper is to determine the actual dynamics of the formation of upper tree line in eastern Serbia and to identify the recent factors which condition it. The results obtained show that preconditions have been accomplished for the upper tree line increase, but this has not completely been confirmed by previous field researches. Key words: Upper tree line, climate changes, temperature gradient, Mt. Stara Planina, anthropogenic influence, depopula- tion. UDC 574:551.583(497.11-11) INTRODUCTION the upper tree line in eastern Serbia and to identify some of the recent factors by which it is conditioned. In conditions when changes in abiotic and biotic en- The Stara Planina mountain, as the most prominent vironment are intense and diverse, the question aris- high-altitude zone of the region, was examined. The es as to the origin and magnitude of potential factors study assumes that changes in the high-altitude lim- that influence the location, i.e. changes in elevation of its of forest spreading occurs in response to changes the upper tree line. -

C073p135.Pdf

Vol. 73: 135–150, 2017 CLIMATE RESEARCH Published August 21 https://doi.org/10.3354/cr01465 Clim Res Contribution to CR Special 34 ‘SENSFOR: Resilience in SENSitive mountain FORest ecosystems OPENPEN under environmental change’ ACCESSCCESS Drivers of treeline shift in different European mountains Pavel Cudlín1,*, Matija Klop<i<2, Roberto Tognetti3,4, Frantisek Máliˇs5,6, Concepción L. Alados7, Peter Bebi8, Karsten Grunewald9, Miglena Zhiyanski10, Vlatko Andonowski11, Nicola La Porta12, Svetla Bratanova-Doncheva13, Eli Kachaunova13, Magda Edwards-Jonášová1, Josep Maria Ninot14, Andreas Rigling15, Annika Hofgaard16, Tomáš Hlásny17, Petr Skalák1,18, Frans Emil Wielgolaski19 1Global Change Research Institute CAS, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Cˇ eské Bude˘jovice 370 05, Czech Republic 2University of Ljubljana, Biotechnical Faculty, Department of Forestry and Renewable Forest Resources, Slovenia 3Dipartimento di Bioscienze e Territorio, Iniversità degli Studio del Molise, Contrada Fonte Lappone, 86090 Pesche, Italy 4MOUNTFOR Project Centre, European Forest Institute, 38010 San Michele all Adige (Trento), Italy 5Technical University Zvolen, Faculty of Forestry, 960 53 Zvolen, Slovakia 6National Forest Centre, Forest Research Institute Zvolen, 960 92 Zvolen, Slovakia 7Pyrenean Institute of Ecology (CSIC), Apdo. 13034, 50080 Zaragoza, Spain 8WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF, 7260 Davos Dorf, Switzerland 9Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development, 01217 Dresden, Germany 10Forest Research Institute, -

Age-Dependent Growth Responses to Climate from Trees in Himalayan Treeline

ISSN: 2705-4403 (Print) & 2705-4411 (Online) www.cdztu.edu.np/njz Vol. 4 | Issue 1| August 2020 Research Article https://doi.org/10.3126/njz.v4i1.30669 Age-dependent growth responses to climate from trees in Himalayan treeline Achyut Tiwari1* 1 Central Department of Botany, Institute of Science and Technology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 July 2019 | Revised: 24 July 2020 | Accepted: 27 July 2020 Abstract Tree rings provide an important biological archive for climate history in relation to the physiological mechanism of tree growth. Higher elevation forests including treelines are reliable indicators of climatic changes, and tree growth at most elevational treelines are sensitive to temperature at moist regions, while it is sensitive to moisture in semi-arid regions. However, there has been very less pieces of evidence regarding the age-related growth sensitivity of high mountain tree species. This study identified the key difference on the growth response of younger (<30 years of age) and older (>30 years) Abeis spectabilis trees from treeline ecotone of the Trans-Himalayan region in central Nepal. The adult trees showed a stronger positive correlation with precipitation (moisture) over juveniles giving the evidence of higher demand of water for adult trees, particularly in early growth seasons (March to May). The relationship between tree ring width indices and mean temperature was also different in juveniles and adult individuals, indicating that the juveniles are more sensitive to temperature whereas the adults are more sensitive to moisture availability. It is emphasized that the age-dependent growth response to climate has to be considered while analyzing the growth-climate relationship of high mountain tree populations.