Saint James Major C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Byzantine 13th Century Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne c. 1260/1280 tempera on linden panel painted surface: 82.4 x 50.1 cm (32 7/16 x 19 3/4 in.) overall: 84 x 53.5 cm (33 1/16 x 21 1/16 in.) framed: 90.8 x 58.3 x 7.6 cm (35 3/4 x 22 15/16 x 3 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.1 ENTRY The painting shows the Madonna seated frontally on an elaborate, curved, two-tier, wooden throne of circular plan.[1] She is supporting the blessing Christ child on her left arm according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria.[2] Mary is wearing a red mantle over an azure dress. The child is dressed in a salmon-colored tunic and blue mantle; he holds a red scroll in his left hand, supporting it on his lap.[3] In the upper corners of the panel, at the height of the Virgin’s head, two medallions contain busts of two archangels [fig. 1] [fig. 2], with their garments surmounted by loroi and with scepters and spheres in their hands.[4] It was Bernard Berenson (1921) who recognized the common authorship of this work and Enthroned Madonna and Child and who concluded—though admitting he had no specialized knowledge of art of this cultural area—that they were probably works executed in Constantinople around 1200.[5] These conclusions retain their authority and continue to stir debate. -

Tema 7. La Pintura Italiana De Los Siglos Xiii Y Xiv: El Trecento Y Sus Principales Escuelas

TEMA 7. LA PINTURA ITALIANA DE LOS SIGLOS XIII Y XIV: EL TRECENTO Y SUS PRINCIPALES ESCUELAS 1. La pintura italiana del Duecento: la influencia bizantina Con el siglo XIII, tiene lugar la aparición de un nuevo espíritu religioso que supone un cambio trascendental en el pensamiento europeo y se produce de la mano de las órdenes religiosas mendicantes: franciscanos y dominicos. Su labor marca la renovación del pensamiento gótico dando lugar a una religiosidad basada en el acercamiento al hombre como camino hacia Dios. Ambas órdenes se instalan en las ciudades para predicar a un mayor número de fieles y luchar contra la herejía, poniendo en práctica las virtudes de la pobreza y la penitencia. Se generarán toda una serie de obras arquitectónicas, escultóricas y pictóricas con una nueva y rica iconografía que tendrá una importante repercusión en toda Europa a lo largo del siglo XIV. La Maiestas Domini, va a ser sustituidas progresivamente por la Maiestas Sanctorum, es decir, por la narración de las vidas de los santos, que ocupan la decoración de las capillas privadas en los templos. Del mismo modo, la Virgen deja de ser trono de Dios para convertirse en Madre y por tanto en la intermediaria entre Dios y los hombres. En esta tendencia a humanizar a los personajes sagrados aparece la imagen del Cristo doloroso, en la que el sufrimiento de Jesús alcanza un expresionismo impensable en el románico. No podemos dejar de referirnos al nacimiento de la Escolástica, que surge de forma paralela pero muy relacionada con estas órdenes mendicantes, con la creación de las universidades y la traducción de obras aristotélicas realizadas a partir del siglo XII. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

February 2, 2020

Feast of the Presentation of the Lord Lumen ad revelationem gentium February 1-2, 2020 Readings: Malachi 3:1-4; Hebrews 2:14-18; Luke 2:22-40 You never know what is hiding in plain sight. Consider what was hanging above the hotplate in the kitchen of an elderly woman in Compiègne, France. In fact, the painting was authenticated as “Christ Mocked,” a masterpiece attributed to Cimabue, the 13th- century Italian forefather of the Italian Renaissance who painted the fresco of St. Francis of Assisi in the basilica, widely thought to be the saint’s best likeness. Her painting sold for a cool 24 M Euro! Have you ever wondered what’s on your bookshelf? In 1884, while rummaging through an obscure Tuscan monastery library, a scholar discovered a 22-page copy (dating from the 9th century) of a late 4th century travel diary detailing an extended pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The account was written by an intrepid woman named Egeria, whose curiosity was only matched by her deep piety. It reveals that early Christian worship was chock full of signs and symbols, including a liturgical year with Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter and Pentecost. It also includes the earliest evidence of today’s feast.1 Talk about a barn find! She related that today’s feast: “is undoubtedly celebrated here with the very highest honor, for on that day there is a procession, in which all take part... All the priests, and after them the bishop, preach, always taking for their subject that part of the Gospel where Joseph and Mary brought the Lord into the Temple on the fortieth day.”2 Christ is indeed the Light of the Nations. -

Roberto Longhi E Giulio Carlo Argan. Un Confronto Intellettuale Luiz Marques Universidade Estadual De Campinas - UNICAMP

NUMERO EDITORIALE ARCHIVIO REDAZIONE CONTATTI HOME ATTUALE Roberto Longhi e Giulio Carlo Argan. Un confronto intellettuale Luiz Marques Universidade Estadual de Campinas - UNICAMP 1. Nel marzo del 2012 ha avuto luogo a Roma, all’Accademia dei Lincei e a Villa Medici, un Convegno sul tema: “Lo storico dell’arte intellettuale e politico. Il ruolo degli storici dell’arte nelle politiche culturali francesi e italiane”[1]. L’iniziativa celebrava il centenario della nascita di Giulio Carlo Argan (1909) e di André Chastel (1912), sottolineando l’importanza di queste due grandi figure della storiografia artistica italiana e francese del XX secolo. La celebrazione fornisce l’occasione per proporsi di fare, in modo molto modesto, un confronto intellettuale tra Roberto Longhi (1890-1970)[2] e Giulio Carlo Argan (1909-1992)[3], confronto che, a quanto ne so, non ha finora tentato gli studiosi. Solo Claudio Gamba allude, di passaggio, nel suo profilo biografico di Argan, al fatto che questo è “uno dei classici della critica del Novecento, per le sue indubitabili doti di scrittore, così lucidamente razionale e consapevolmente contrapposto alla seduttrice prosa di Roberto Longhi”[4]. Un contrappunto, per quello che si dice, poco più che di “stile”, e nient’altro. E ciò non sorprende. Di fatto, se ogni contrappunto pressuppone logicamente un denominatore comune, un avvicinamento tra i due grandi storici dell’arte pare – almeno a prima vista – scoraggiante, tale è la diversità di generazioni, di linguaggi, di metodi e, soprattutto, delle scelte e delle predilezioni che li hanno mossi. Inoltre, Argan è stato notoriamente il grande discepolo e successore all’Università di Roma ‘La Sapienza’ di Lionello Venturi (1885-1961), il cui percorso fu contrassegnato da conflitti con quello di Longhi[5]. -

Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Master of Città di Castello Italian, active c. 1290 - 1320 Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) c. 1290 tempera on panel painted surface: 230 × 141.5 cm (90 9/16 × 55 11/16 in.) overall: 240 × 150 × 2.4 cm (94 1/2 × 59 1/16 × 15/16 in.) framed: 252.4 x 159.4 x 13.3 cm (99 3/8 x 62 3/4 x 5 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.77 ENTRY This panel, of large dimensions, bears the image of the Maestà represented according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria. [1] This type of Madonna and Child was very popular among lay confraternities in central Italy; perhaps it was one of them that commissioned the painting. [2] The image is distinguished among the paintings of its time by the very peculiar construction of the marble throne, which seems to be formed of a semicircular external structure into which a circular seat is inserted. Similar thrones are sometimes found in Sienese paintings between the last decades of the thirteenth and the first two of the fourteenth century. [3] Much the same dating is suggested by the delicate chrysography of the mantles of the Madonna and Child. [4] Recorded for the first time by the Soprintendenza in Siena c. 1930 as “tavola preduccesca,” [5] the work was examined by Richard Offner in 1937. In his expertise, he classified it as “school of Duccio” and compared it with some roughly contemporary panels of the same stylistic circle. -

Schaums Outline of Italian Vocabulary, Second Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SCHAUMS OUTLINE OF ITALIAN VOCABULARY, SECOND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Luigi Bonaffini | 288 pages | 24 Mar 2011 | McGraw-Hill Education - Europe | 9780071755481 | English | United States Schaums Outline of Italian Vocabulary, Second Edition PDF Book Find out more here. A word is a combination of phonemes. With nouns denoting family members preceded by possessive adjectives. There are no plural forms. The coins are as follows: lc or E 0. Complete the following with the correct definite article: 1. Dramatically raise your ACT score with this go-to study guide filled with test-taking tips, practice tests and more! Avere and Essere. Chi colui che, colei che, coloro che. Complete the following with the appropriate words for the relative superlative: 1. No trivia or quizzes yet. Special use of Duecento, Trecento, etc. Irregular verbs. Book in almost Brand New condition. Enter in each space provided an appropriate word from the list below that corresponds with the underlined sound produced by the English word in parentheses, and fits well in the context of each sentence. Complete the following with the appropriate form of the indicated adjective s : 1. Queste cravatte sono blu. Supply the correct form of the titles provided. Many compound nouns are formed by uniting two separate nouns. Tu ti vesti come me. On the structure and affinities of the tabulate corals of the Palaeozoic period PDF. Don Giuseppe suona il mandolino. The Postal Service Guide to U. This cat m. Fortunately for you, there's Schaum's Outlines. Observe the following: Ste-fa-no sim-pa-ti-co U. Religious Education PDF. -

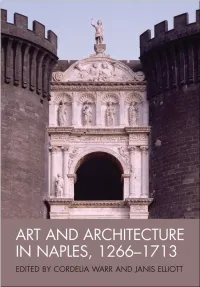

Art and Architecture in Naples, 1266-1713 / Edited by Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott

This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 NEW APPROACHES EDITED BY CORDELIA WARR AND JANIS ELLIOTT This edition first published 2010 r 2010 Association of Art Historians Originally published as Volume 31, Issue 4 of Art History Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley- Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. -

Religious Imagery of the Italian Renaissance

Religious Imagery of the Italian Renaissance Structuring Concepts • The changing status of the artist • The shift from images and objects that are strictly religious to the idea of Art • Shift from highly iconic imagery (still) to narratives (more dynamic, a story unfolding) Characteristics of Italian Images • Links to Byzantine art through both style and materials • References to antiquity through Greco-Roman and Byzantine cultures • Simplicity and monumentality of forms– clearing away nonessential or symbolic elements • Emphasizing naturalism through perspective and anatomy • The impact of the emerging humanism in images/works of art. TIMELINE OF ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: QUATROCENTO, CINQUECENTO and early/late distinctions. The Era of Art In Elizabeth’s lecture crucifixex, she stressed the artistic representations of crucifixions as distinct from more devotional crucifixions, one of the main differences being an attention paid to the artfulness of the images as well as a break with more devotional presentations of the sacred. We are moving steadily toward the era which Hans Belting calls “the Era of Art” • Artists begin to sign their work, take credit for their work • Begin developing distinctive styles and innovate older forms (rather than copying) • A kind of ‘cult’ of artists originates with works such as Georgio Vasari one of the earliest art histories, The Lives of the Artists, which listed the great Italian artists, as well as inventing and developing the idea of the “Renaissance” Vasari’s writing serves as a kind of hagiography of -

Art Basel Ferrari & Ducati Interview Seaports

December 2007 - Vol.4 No. 4 A periodic publication from the ART BASEL Discovering Southern Italian Design FERRARI & DUCATI Champions of Italian Technology INTERVIEW Prof. Camillo Ricordi SEAPORTS Ft. Lauderdale - Olbia Cooperation .4 .6 Business | Affari Business | Affari Art Basel: Discovering Champions of Italian Southern Italian Design Technology .9 Business | Affari INDEX Luxury Cars .14 .18 Events | Eventi Interview | Italian Investments Intervista in the Southeast Prof. Camillo Ricordi .20 Business | Affari .25 Olbia – Ft. Lauderdale Culture | Cultura Seaports Cooperation EUArt .27 Business Lounge .32 Trade Shows and .30 Exhibitions in New Members USA and Italy .1 Board Members Honorary President: Hon. Marco Rocca President: Giampiero Di Persia Executive Vice-President: Marco Ferri, Esq. Vice-President: Francesco Facilla Treasurer: Roberto Degl’Innocenti Secretary: Joseph L. Raia, Esq. Directors: Sara Bragagia Michele Cometto Chandler R. Finley, Esq. Arthur Furia, Esq. Amedeo Guazzini Paolo Romanelli, M.D. Staff: Executive Director: Silvia Cadamuro Business Development Coord.: Nevio Boccanera Marketing Services: Francesca Tanti Trade Officer: Francesca Lodi Junior Trade Officer: Kristen Maag Contributing to this issue of .IT Supervision: Chandler R. Finley and Alessandro Rancati Project Management: Nevio Boccanera Content: Nevio Boccanera A periodic publication from the Italy-America Cham- Krystle Cacci ber of Commerce Southeast www.iacc-miami.com Silvia Cadamuro Francesca Tanti Cover: “Vesuvius” floor lamp from Mundus Vivendi Translations: -

Humanism and Education in Medieval and Renaissance

Cambridge University Press 0521401925 - Humanism and Education in Medieval and Renaissance Italy: Tradition and Innovation in Latin Schools from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Century - Robert Black Frontmatter More information HUMANISM AND EDUCATION IN MEDIEVAL AND RENAISSANCE ITALY This is the first comprehensive study of the school curriculum in medieval and Renaissance Italy. Robert Black’s analysis finds that the real innovators in the history of Latin education in Italy were the thirteenth-century schoolmasters who introducedanew methodof teaching grammar basedon logic, andtheir early fourteenth- century successors, who first began to rely on the vernacular as a tool to teach Latin grammar. Thereafter, in the later fourteenth andfor most of the fifteenth century, conservatism, not innovation, charac- terizedthe earlier stages of education. The studyof classical texts in medieval Italian schools reached a highpoint in the twelfth century but then collapsedas universities rose in importance duringthe thir- teenth century, a sharp decline only gradually reversed in the two centuries that followed. Robert Black demonstrates that the famous humanist educators did not introduce the revolution in the class- room that is usually assumed, and that humanism did not make a significant impact on school teaching until the later fifteenth century. Humanism and Education is a major contribution to Renaissance studies, to Italian history and to the history of European education, the fruit of sustained manuscript research over many years. ’ publications include Benedetto Accolti and the Florentine Renaissance (), Romance and Aretine Humanism in Sienese Comedy (with Louise George Clubb, ), Studio e Scuola in Arezzo durante il medioevo e Rinascimento () and Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy in Italian Medieval and Renaissance Education (with Gabriella Pomaro, ). -

Early Renaissance Italian Art

Dr. Max Grossman ARTH 3315 Fox Fine Arts A460 Spring 2019 Office hours: T 9:00-10:15am, Th 12:00-1:15pm CRN# 22554 Office tel: 915-747-7966 T/Th 3:00-4:20pm [email protected] Fox Fine Arts A458 Early Renaissance Italian Art The two centuries between the birth of Dante Alighieri in 1265 and the death of Cosimo de’ Medici in 1464 witnessed one of the greatest artistic revolutions in the history of Western civilization. The unprecedented economic expansion in major Italian cities and concomitant spread of humanistic culture and philosophy gave rise to what has come to be called the Renaissance, a complex and multifaceted movement embracing a wide range of intellectual developments. This course will treat the artistic production of the Italian city-republics in the late Duecento, Trecento and early Quattrocento, with particular emphasis on panel and fresco painting in Siena, Florence, Rome and Venice. The Early Italian Renaissance will be considered within its historical, political and social context, beginning with the careers of Duccio di Buoninsegna and Giotto di Bondone, progressing through the generation of Gentile da Fabriano, Filippo Brunelleschi and Masaccio, and concluding with the era of Leon Battista Alberti and Piero della Francesca. INSTRUCTOR BIOGRAPHY Dr. Grossman earned his B.A. in Art History and English at the University of California- Berkeley, and his M.A., M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Art History at Columbia University. After seven years of residence in Tuscany, he completed his dissertation on the civic architecture, urbanism and iconography of the Sienese Republic in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.