Race, National Identity and Responses to Muhammad Ali in 1960S Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNE MOWBRAY, DUCHESS of YORK: a 15Th-CENTURY CHILD BURIAL from the ABBEY of ST CLARE, in the LONDON BOROUGH of TOWER HAMLETS

London and Middlesex Archaeological Society Transactions, 67 (2016), 227—60 ANNE MOWBRAY, DUCHESS OF YORK: A 15th-CENTURY CHILD BURIAL FROM THE ABBEY OF ST CLARE, IN THE LONDON BOROUGH OF TOWER HAMLETS Bruce Watson and †William White With contributions by Barney Sloane, Dorothy M Thorn and Geoffrey Wheeler, and drawing on previous research by J P Doncaster, H C Harris, A W Holmes, C R Metcalfe, Rosemary Powers, Martin Rushton, †Brian Spencer and †Roger Warwick SUMMARY FOREWORD Dorothy M Thorn (written 2007) In 1964 during the redevelopment of the site of the church of the Abbey of St Clare in Tower Hamlets, a During the 1960s, my future husband, the masonry vault containing a small anthropomorphic late James Copland Thorn FSA, and I were lead coffin was discovered. The Latin inscription actively involved in London archaeology as attached to the top of the coffin identified its occupant part of Dr Francis Celoria’s digging team.1 as Anne Mowbray, Duchess of York. She was the child Naturally all the members of the group bride of Richard, Duke of York, the younger son of were very interested in such an important Edward IV. Anne died in November 1481, shortly discovery, and when Anne Mowbray was before her ninth birthday. As the opportunity to study identified we were all impressed (possibly scientifically a named individual from the medieval no-one more so than James). When the day period is extremely rare, the London Museum quickly came for Anne Mowbray to be reburied in organised a comprehensive programme of analysis, Westminster Abbey, the BBC wanted to which included the study of Anne’s life, her hair, teeth, interview Celoria, but he could not be found, skeletal remains and the metallurgy of her coffin. -

Welcome WHAT IS IT ABOUT GOLF? EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN

EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN HEADLAND James Watson and Steve Crosdale, both former side of the business, as well as the practical. greenkeepers with a total of 24 years experience in "This position provides the ideal opportunity to the industry behind them, join Headland Amenity concentrate on this area and help customers as Regional Technical Managers. achieve the best possible results from a technical Welcome James has responsibility for South East England, perspective," he said. including South London, Surrey, Sussex and Kent, James, whose father retired as a Course while Steve Crosdale takes East Anglia and North Manager in December, and who practised the London including Essex, profession himself for 14 years before moving into WHAT IS IT Hertfordshire and sales a year ago, says that he needed a new ABOUT GOLF? Cambridgeshire. challenge but wanted something where he could As I write the BBC are running a series of Andy Russell, use his experience built programmes in conjunction with the 50th Headland's Sales and up on golf courses anniversary of their Sports Personality of the Year Marketing Director said around Europe. Award with a view to identifying who is the Best of that the creation of these "This way I could the Best. two new posts is take a leap of faith but I Most sports are represented. Football by Bobby indicative of the way the didn't have to leap too Moore, Paul Gascoigne, Michael Owen and David company is growing. Beckham. Not, surprisingly, by George Best, who was James Watson far," he explains. "I'm beaten into second place by Princess Anne one year. -

Ebook Download Muhammad Ali Ebook, Epub

MUHAMMAD ALI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Thomas Hauser | 544 pages | 15 Jun 1992 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780671779719 | English | New York, United States Muhammad Ali PDF Book Retrieved May 20, Retrieved November 5, Federal Communications Commission. Vacant Title next held by George Foreman. Irish Independent. Get used to me. Sonny Liston - Boxen". Ellis Ali vs. Ali conceded "They didn't tell me about that in America", and complained that Carter had sent him "around the world to take the whupping over American policies. The Guardian. Armed Forces, but he refused three times to step forward when his name was called. Armed Forces qualifying test because his writing and spelling skills were sub-standard, [] due to his dyslexia. World boxing titles. During his suspension from , Ali became an activist and toured around the world speaking to civil rights organizations and anti-war groups. Croke Park , Dublin , Ireland. But get used to me — black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. In winning this fight at the age of 22, Clay became the youngest boxer to take the title from a reigning heavyweight champion. Ali later used the "accupunch" to knockout Richard Dunn in Retrieved December 27, In , the Associated Press reported that Ali was tied with Babe Ruth as the most recognized athlete, out of over dead or living athletes, in America. His reflexes, while still superb, were no longer as fast as they had once been. Following this win, on July 27, , Ali announced his retirement from boxing. After his death she again made passionate appeals to be allowed to mourn at his funeral. -

Boxing Edition

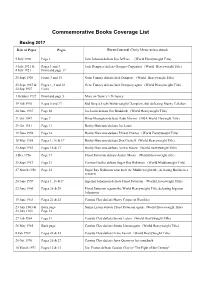

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Muhammad Ali Biography

Muhammad Ali Biography “I’m not the greatest; I’m the double greatest. Not only do I knock ’em out, I pick the round. “ – Muhammad Ali Short Biography Muhammad Ali Muhammad Ali (born Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr. on January 17, 1942) is a retired American boxer. In 1999, Ali was crowned “Sportsman of the Century” by Sports Illustrated. He won the World Heavyweight Boxing championship three times, and won the North American Boxing Federation championship as well as an Olympic gold medal. Ali was born in Louisville, Kentucky. He was named after his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay, Sr., (who was named for the 19th century abolitionist and politician Cassius Clay). Ali later changed his name after joining the Nation of Islam and subsequently converted to Sunni Islam in 1975. Early boxing career Standing at 6’3″ (1.91 m), Ali had a highly unorthodox style for a heavyweight boxer. Rather than the normal boxing style of carrying the hands high to defend the face, he instead relied on his ability to avoid a punch. In Louisville, October 29, 1960, Cassius Clay won his first professional fight. He won a six-round decision over Tunney Hunsaker, who was the police chief of Fayetteville, West Virginia. From 1960 to 1963, the young fighter amassed a record of 19-0, with 15 knockouts. He defeated such boxers as Tony Esperti, Jim Robinson, Donnie Fleeman, Alonzo Johnson, George Logan, Willi Besmanoff, Lamar Clark (who had won his previous 40 bouts by knockout), Doug Jones, and Henry Cooper. Among Clay’s victories were versus Sonny Banks (who knocked him down during the bout), Alejandro Lavorante, and the aged Archie Moore (a boxing legend who had fought over 200 previous fights, and who had been Clay’s trainer prior to Angelo Dundee). -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25Th Dec, 2008

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25th DEc, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My very best wishes to all my readers and thank you for the continued support you have given which I do appreciate a great deal. Name: Willie Pastrano Career Record: click Birth Name: Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano Nationality: US American Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Born: 1935-11-27 Died: 1997-12-06 Age at Death: 62 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Trainers: Angelo Dundee & Whitey Esneault Manager: Whitey Esneault Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano was born in the Vieux Carrê district of New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 November 1935. He had a hard upbringing, under the gaze of a strict father who threatened him with the belt if he caught him backing off from a confrontation. 'I used to run from fights,' he told American writer Peter Heller in 1970. 'And papa would see it from the steps. He'd take his belt, he'd say "All right, me or him?" and I'd go beat the kid: His father worked wherever and whenever he could, in shipyards and factories, sometimes as a welder, sometimes as a carpenter. 'I remember nine dollars a week paychecks,' the youngster recalled. 'Me, my mother, my step-brother, and my father and whatever hangers-on there were...there were always floaters in the family.' Pastrano was an overweight child but, like millions of youngsters at the time, he wanted to be a sports star like baseball's Babe Ruth. -

Wbc´S Lightweight World Champions

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL Jose Sulaimán WBC HONORARY POSTHUMOUS LIFETIME PRESIDENT (+) Mauricio Sulaimán WBC PRESIDENT WBC STATS WBC HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT BARCLAYS CENTER / BROOKLYN, NEW YORK, USA NOVEMBER 4, 2017 THIS WILL BE THE WBC’S 1, 986 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN ITS 54 YEARS OF HISTORY LOU DiBELLA & DiBELLA ENTERTAINMENT, PRESENTS: DEONTAY WILDER (US) BERMANE STIVERNE (HAITI/CAN) WBC CHAMPION WBC Official Challenger (No. 1) Nationality: USA Nationality: Canada Date of Birth: October 22, 1985 Date of Birth: November 1, 1978 Birthplace: Tuscaloosa, Alabama Birthplace: La Plaine, Haiti Alias: The Bronze Bomber Alias: B Ware Resides in: Tuscaloosa, Alabama Resides in: Las Vegas, Nevada Record: 38-0-0, 37 KO’s Record: 25-2-1, 21 KO’s Age: 32 Age: 39 Guard: Orthodox Guard: Orthodox Total rounds: 112 Total rounds: 107 WBC Title fights: 6 (6-0-0) World Title fights: 2 (1-1-0) Manager: Jay Deas Manager: James Prince Promoter: Al Haymon / Lou Dibella Promoter: Don King Productions WBC´S HEAVYWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. SONNY LISTON (US) (+) 1963 - 1964 2. MUHAMMAD ALI (US) 1964 – 1967 3. JOE FRAZIER (US) (+) 1968 - 1973 4. GEORGE FOREMAN (US) 1973 - 1974 5. MUHAMMAD ALI (US) * 1974-1978 6. LEON SPINKS (US) 1978 7. KEN NORTON (US) 1977 - 1978 8. LARRY HOLMES (US) 1978 - 1983 9. TIM WITHERSPOON (US) 1984 10. PINKLON THOMAS (US) 1984 - 1985 11. TREVOR BERBICK (CAN) 1986 12. MIKE TYSON (US) 1986 - 1990 13. JAMES DOUGLAS (US) 1990 14. EVANDER HOLYFIELD (US) 1990 - 1992 15. RIDDICK BOWE (US) 1992 16. LENNOX LEWIS (GB) 1993 - 1994 17. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

Fight Record Brian London (Blackpool)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Brian London (Blackpool) Active: 1955-1970 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 58 contests (won: 37 lost: 20 drew: 1) Fight Record 1955 Mar 22 Dennis Lockton (Manchester) WRSF1(6) Royal Albert Hall, Kensington Source: Boxing News 25/03/1955 pages 8, 09 and 12 London 13st 10lbs Lockton 13st 4lbs 8ozs Apr 18 Frank Walshaw (Barnsley) WKO2 Pershore Road Stadium, Birmingham Source: Boxing News 22/04/1955 page 11 London 13st 7lbs Walshaw 13st 11lbs May 23 Hugh McDonald (Glasgow) WKO2(8) Engineers Club, West Hartlepool Source: Boxing News 27/05/1955 page 11 McDonald boxed for the Scottish Heavyweight Title 1951. London 13st 9lbs 8ozs McDonald 17st 4lbs Jun 6 Dinny Powell (Walworth) WKO6(6) New St James Hall, Newcastle Source: Boxing News 10/06/1955 page 9 London 13st 9lbs 8ozs Powell 13st 3lbs 4ozs Jul 11 Paddy Slavin (Belfast) WRSF2 Engineers Club, West Hartlepool Source: Boxing News 15/07/1955 page 11 Slavin was Northern Ireland Area Heavyweight Champion 1948. London 13st 7lbs 8ozs Slavin 14st 1lbs 4ozs Aug 8 Robert Eugene (Belgium) WPTS(8) Engineers Club, West Hartlepool Source: Boxing News 12/08/1955 page 12 London 13st 8lbs Eugene 16st 9lbs Oct 7 Jose Gonzalez (Spain) WRTD3 Belle Vue, Manchester Source: Boxing News 14/10/1955 pages 8 and 9 London 13st 8lbs 12ozs Gonzalez 13st 2lbs 8ozs Oct 24 Simon Templar (Burton-on-Trent) WRSF7(8) Farrer Street Stadium, Middlesbrough Source: Boxing -

Richard Hoggart Collection Shelf Number Title Author/Publisher/Year

Richard Hoggart Collection Shelf Title Author/Publisher/Year Notes Number Fly-leaf inscribed 'Mary Hoggart, Richard, (London : Chatto & 1 Auden : an introductory essay. Hoggart, Hull, July 1951'. Windus 1951.) With a few corrections Hoggart, Richard, (London : Published for Half t.p. inscribed 'To 2 W.H. Auden. the British Council and the National Book Grandma & Grandad, with League by Longmans Green 1957.) love, Richard' Hoggart, Richard, (London : Published for 2A W.H. Auden. the British Council and the National League by Longmans Green 1957.) Hoggart, Richard, (London : Longmans 2B W.H. Auden. Green and Co for the British Council and the National League 1966.) Hoggart, Richard, (London : Longmans Fly leaf inscribed 'Richard 3 W.H. Auden / edited by Ian Scott-Kilvert. Green and Co for the British Council 1977.) Hoggart' Fly leaf inscribed 'Mary The uses of literacy : aspects of working-class life with Hoggart, Richard, (London : Chatto & Hoggart, Rochester, March 4 special reference to publications and entertainments / Windus 1957.) 1957'. With a few pencilled Richard Hoggart. annotations The uses of literacy / Richard Hoggart ; introduction by Hoggart, Richard, (New Brunswick, N.J., Disbound pre-publication 5 Andrew Goodwin ; with a new postscript by John U.S.A. : Transaction Publishers c1998.) copy Corner. La culture du pauvre : étude sur le style de vie des Fly-leaf inscribed 'Mary & classes populaires en Angleterre / Richard Hoggart ; Richard Hoggart, Paris, Hoggart, Richard, (Paris : Editions de minuit 6 traduction de Françoise et Jean Claude Garcias et de October 70', now partially 1970.) Jean-Claude Passeron, présentation et index de Jean- obliterated through water Claude Passeron. -

JSC-Bar-Menu-March-2019.Pdf

As teenage boxer Kid Mears stepped through the ropes, into the ring, his young girlfriend Fay could scarcely bear to watch. Later that evening she issued an ultimatum: “It’s the ring or me!” Jack Solomons discarded his gloves and his nickname and concentrated on his day job, hawking fish from a stall on Petticoat Lane market. He and Fay were swiftly married and remained together until her death 25 years later. Jack had too good a brain to have it exposed to the brutality of life in the boxing ring, after he figured out that the real money, and the longer career, was in promoting bouts he left his day job to return to his ultimate calling. Jack Solomons went on to become one of the greatest boxing promoters in history. Initially, Jack’s speciality was in putting on young, up & coming boxers not handled by the established business. Jack Solomons Gym was originally based in the Devonshire Sporting Club, off Mare Street in Hackney until it was destroyed by German bombs in 1940. After this, Jack Solomons boxing gym found a new home in Great Windmill Street. In 1945 Solomons hit it big with the Jack London vs Bruce Woodcock British heavyweight title fight at White Hart Lane. Following this Jack took on the big British fighters of the day such as Freddie Mills and Randolph Turpin. Jack promoted the sensational bout in 1951 when Sugar Ray Robinson lost his middleweight world title to Turpin. In 1963, he brought Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) to England to fight Henry Cooper. -

The Evolving Role of the Solo Euphonium in Orchestral Music: An

THE EVOLVING ROLE OF THE SOLO EUPHONIUM IN ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: AN ANALYSIS OF LORIN MAAZEL’S MUSIC FOR FLUTE AND ORCHESTRA WITH TENOR TUBA OBBLIGATO AND KARL JENKINS’S CANTATA MEMORIA Boonyarit Kittaweepitak, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2020 APPROVED: David Childs, Major Professor Eugene M. Corporon, Committee Member Donald C. Little, Committee Member Natalie Mannix, Interim Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Felix Olschofka, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kittaweepitak, Boonyarit. The Evolving Role of the Solo Euphonium in Orchestral Music: An Analysis of Lorin Maazel’s “Music for Flute and Orchestra with Tenor Tuba Obbligato” and Karl Jenkins’s “Cantata Memoria.” Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2020, 52 pp., 15 musical examples, 7 appendices, bibliography, 24 titles. The euphonium has been an integral part of wind bands and brass bands for more than a century. During this time the instrument has grown in stature in both types of band, as an ensemble member and a solo instrument. Until recently, however, the instrument has been underrepresented in orchestral literature, although a growing number of composers are beginning to appreciate the characteristics of the instrument. The purpose of this research is to explore the perceived rise of the euphonium in an orchestral environment through analyzing the significance of the role it plays within Lorin Maazel’s Music for Flute with Tenor Tuba Obbligato (1995) and Karl Jenkins’ Cantata Memoria (2005); specifically, how the euphonium contributes to the orchestral scores in relation to its capabilities as an instrumental voice.