Protected Areas in Chilean Patagonia CARLOS CUEVAS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Cruise

EXTEND YOUR JOURNEY BEFORE OR AFTER YOUR CRUISE 2019 WORLD CRUISE Join us for the journey of a lifetime PRE: MIAMI, USA – FROM $1,069 PER PERSON POST: LONDON, ENGLAND – FROM $1,339 PER PERSON INCLUDES: INCLUDES: • 2 nights in Miami at the Loews Miami Beach Hotel (or similar) • 2 nights in London at the Conrad London St. James (or similar) • Meals: 2 breakfasts • Meals: 2 breakfasts and 1 lunch • Bon Voyage Wine and Cheese Reception • Farewell Wine and Cheese Reception • Guided City Tour • Guided City Tour • Services of a Viking Host • Services of a Viking Host • All transfers • All transfers See vikingcruises.com.au/oceans for details. NO KIDS | NO CASINOS | VOTED WORLD’S BEST 138 747 VIKINGCRUISES.COM.AU OR SEE YOUR LOCAL TRAVEL AGENT VIK0659 Brochure_World_Cruise_8pp_A4(A3)_VIK0659.indd 1 23/8/17 16:52 ENGLAND London (Greenwich) Vigo SPAIN USA Casablanca MOROCCO Pacific Miami Santa Cruz de Tenerife Ocean Atlantic Canary Islands Ocean SPAIN San Juan Dakar PUERTO RICO SENEGAL International Date Line St. George’s GRENADA Îles du Salut FRENCH GUIANA FRENCH POLYNESIA BRAZIL MADAGASCAR Recife Bora Bora (Vaitape) Salvador de Bahia Atlantic NAMIBIA Fort Dauphin Easter Island Ocean CHILE Armação dos Búzios MOZAMBIQUE Tahiti (Papeete) Santiago Rio de Janeiro Walvis Bay (Valparaíso) Maputo Perth AUSTRALIA FRENCH CHILE URUGUAY Lüderitz Port Louis Bay of Islands MAURITIUS (Freemantle) POLYNESIA Durban (Russell) Robinson Crusoe Montevideo Adelaide Sydney East London Auckland Island Buenos Aires Cape Town Port Elizabeth Indian Milford CHILE Melbourne -

Comparison of Alternate Cooling Technologies for California Power Plants Economic, Environmental and Other Tradeoffs CONSULTANT REPORT

Merrimack Station AR-1167 CALIFORNIA ENERGY COMMISSION Comparison of Alternate Cooling Technologies for California Power Plants Economic, Environmental and Other Tradeoffs CONSULTANT REPORT February 2002 500-02-079F Gray Davis, Governor CALIFORNIA ENERGY COMMISSION Prepared By: Electric Power Research Institute Prepared For: California Energy Commission Kelly Birkinshaw PIER Program Area Lead Marwan Masri Deputy Director Technology Systems Division Robert L. Therkelsen Executive Director PIER / EPRI TECHNICAL REPORT Comparison of Alternate Cooling Technologies for California Power Plants Economic, Environmental and Other Tradeoffs This report was prepared as the result of work sponsored by the California Energy Commission. It does not necessarily represent the views of the Energy Commission, its employees or the State of California. The Energy Commission, the State of California, its employees, contractors and subcontractors make no warrant, express or implied, and assume no legal liability for the information in this report; nor does any party represent that the uses of this information will not infringe upon privately owned rights. This report has not been approved or disapproved by the California Energy Commission, nor has the California Energy Commission passed upon the accuracy or adequacy of the information in this report. Comparison of Alternate Cooling Technologies for California Power Plants Economic, Environmental and Other Tradeoffs Final Report, February 2002 Cosponsor California Energy Commission 1516 9th Street Sacramento, CA 95814-5504 Project Managers Matthew S. Layton, Joseph O’Hagan EPRI Project Manager K. Zammit EPRI • 3412 Hillview Avenue, Palo Alto, California 94304 • PO Box 10412, Palo Alto, California 94303 • USA 800.313.3774 • 650.855.2121 • [email protected] • www.epri.com DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTIES AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITIES THIS DOCUMENT WAS PREPARED BY THE ORGANIZATION(S) NAMED BELOW AS AN ACCOUNT OF WORK SPONSORED OR COSPONSORED BY THE ELECTRIC POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE, INC. -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

Rosselló Vislumbra Victoria 2004

SEPTIEMBRE 2003 EL FARO 1 AÑO 5 EDICIÓN 44 CABO ROJO SEPTIEMBRE 2003 GRATIS Rosselló vislumbra victoria 2004 Suplemento a Cabo Rojo. Pag. 11 Con el micrófono, San Padilla Ferrer, junto a Pedro Rosselló, Carlos Romero Barcelo y Norman Ramírez, en actividad del alcalde de Cabo Rojo Por Reinaldo Silvestri residente, Luis Fortuño, y líderes de apuntó. También advirtió que no se El Faro las huestes penepeísta de varias pobla- está haciendo el uso de las prerroga- ciones de la región oeste. tivas que ofrece el mandato guberna- CABO ROJO - Las luchas inter- Rosselló concentró sus argumentos mental cuando no se usan las fuerzas nas en el seno del Partido Popular ante El Faro aludiendo a las pugnas del estado para parar la rampante Miss Cabo Rojo Democrático en cuanto a estilo de internas que ha provocado, según sus criminalidad que impera. Recordó Universe gobernar y el decaimiento de proyec- observaciones, la forma errática de que durante su mandato hubo una tos como la Reforma de Salud, conducir la vida puertorriqueña de la merma sustancial en ese renglón. Pag. 15 y 20 constituyen para el ex gobernador gobernadora Sila María Calderón y El ex gobernador, haciendo refer- penepeísta Pedro Rosselló González muchos de sus altos líderes de la Cá- encia al liderato del Partido Popular, la carta de triunfo a la gobernación mara y del Senado. Muchos de estos alegó que es notable el número de y un nuevo mandato para el Partido mismos líderes han estado cuestion- estos que se sienten de alguna manera Nuevo Progresista. ando públicamente sus vanos esfuer- desilusionados por las imposiciones El ex Primer Mandatario Estatal ex- zos para combatir el alza criminal, al de la Gobernadora, y en especial presó algunos puntos de vista sobre la igual que su fracaso para mantener con las decisiones sobre candidatos situación del país y los efectos que vi- viva la Reforma de Salud, argumentó a posiciones públicas que, a tono ene teniendo su actividad proselitista enfáticamente. -

NSF 03-021, Arctic Research in the United States

This document has been archived. Home is Where the Habitat is An Ecosystem Foundation for Wildlife Distribution and Behavior This article was prepared The lands and near-shore waters of Alaska remaining from recent geomorphic activities such by Page Spencer, stretch from 48° to 68° north latitude and from 130° as glaciers, floods, and volcanic eruptions.* National Park Service, west to 175° east longitude. The immense size of Ecosystems in Alaska are spread out along Anchorage, Alaska; Alaska is frequently portrayed through its super- three major bioclimatic gradients, represented by Gregory Nowacki, USDA Forest Service; Michael imposition on the continental U.S., stretching from the factors of climate (temperature and precipita- Fleming, U.S. Geological Georgia to California and from Minnesota to tion), vegetation (forested to non-forested), and Survey; Terry Brock, Texas. Within Alaska’s broad geographic extent disturbance regime. When the 32 ecoregions are USDA Forest Service there are widely diverse ecosystems, including arrayed along these gradients, eight large group- (retired); and Torre Arctic deserts, rainforests, boreal forests, alpine ings, or ecological divisions, emerge. In this paper Jorgenson, ABR, Inc. tundra, and impenetrable shrub thickets. This land we describe the eight ecological divisions, with is shaped by storms and waves driven across 8000 details from their component ecoregions and rep- miles of the Pacific Ocean, by huge river systems, resentative photos. by wildfire and permafrost, by volcanoes in the Ecosystem structures and environmental Ring of Fire where the Pacific plate dives beneath processes largely dictate the distribution and the North American plate, by frequent earth- behavior of wildlife species. -

Subregional and Regional Approaches for Disaster Resilience

United Nations ESCAP/76/14 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 3 March 2020 Original: English Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Seventy-sixth session Bangkok, 21 May 2020 Item 5 (d) of the provisional agenda* Review of the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Asia and the Pacific: disaster risk reduction Subregional and regional approaches for disaster resilience Note by the secretariat Summary As climate uncertainties grow, Asia and the Pacific faces an increasingly complex disaster riskscape. In the Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2019: The Disaster Riskscape across Asia-Pacific – Pathways for Resilience, Inclusion and Empowerment, the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific provided a comprehensive overview of the regional riskscape, identifying the region’s main hotspots and options for action. Based on the findings, the present document contains highlights of the changing geography of disasters together with the associated multi-hazard risk hotspots at the subregional level, namely, South-East Asia, South and South-West Asia, the Pacific small island developing States, North and Central Asia, and North and East Asia. For each subregion, the document provides specific solution-oriented resilience-building approaches. In this regard, the document contains information about the opportunities to build resilience provided by subregional and regional cooperation and a discussion of the secretariat’s responses under the aegis of the Asia-Pacific Disaster Resilience Network. The Commission may wish to review the present document and provide guidance for the future work of the secretariat. I. Introduction 1. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides a blueprint for development, including ending poverty, fighting inequalities and tackling climate change. -

13 Ship-Breaking.Com

Information bulletin on September 26th, 2008 ship demolition #13 June 7th to September 21st 2008 Ship-breaking.com February 2003. Lightboat, Le Havre. February 2008 © Robin des Bois From June 7th to September 21st 2008, 118 vessels have left to be demolished. The cumulative total of the demolitions will permit the recycling of more than 940,000 tons of metals. The 2008 flow of discarded vessels has not slowed down. Since the beginning of the year 276 vessels have been sent to be scrapped which represents more than 2 millions tons of metals whereas throughout 2007 289 vessels were scrapped for a total of 1.7 milion tons of metals. The average price offered by Bangladeshi and Indian ship breakers has risen to 750-800 $ per ton. The ship owners are taking advantage of these record prices by sending their old vessels to be demolished. Even the Chinese ship breaking yards have increased their price via the purchase of the container ship Provider at 570$ per ton, with prices averaging more than 500 $. However, these high prices have now decreased with the collapse of metal prices during summer and the shipyards are therefore renegotiating at lower price levels with brokers and cash buyers sometimes changing the final destination at the last minute. This was the case of the Laieta, which was supposed to leave for India for 910 $ per ton and was sold to Bangladesh at 750 $ per ton. The price differences have been particularly notable in India; the shipyards prices have returned to 600 $ per ton. From June to September, India with 60 vessels (51%) to demolish, is ahead of Bangladesh with 40 (34%), The United States 8 (7%), China 4 (4%), Turkey 2 (2%), Belgium and Mexico, 1 vessel each (1%). -

Chapter 10 RIPOSTE and REPRISE

Chapter 10 RIPOSTE AND REPRISE ...I have given the name of the Strait of the Mother of God, to what was formerly known as the Strait of Magellan...because she is Patron and Advocate of these regions....Fromitwill result high honour and glory to the Kings of Spain ... and to the Spanish nation, who will execute the work, there will be no less honour, profit, and increase. ...they died like dogges in their houses, and in their clothes, wherein we found them still at our comming, untill that in the ende the towne being wonderfully taynted with the smell and the savour of the dead people, the rest which remayned alive were driven ... to forsake the towne.... In this place we watered and woodded well and quietly. Our Generall named this towne Port famine.... The Spanish riposte: Sarmiento1 Francisco de Toledo lamented briefly that ‘the sea is so wide, and [Drake] made off with such speed, that we could not catch him’; but he was ‘not a man to dally in contemplations’,2 and within ten days of the hang-dog return of the futile pursuers of the corsair he was planning to lock the door by which that low fellow had entered. Those whom he had sent off on that fiasco seem to have been equally, and reasonably, terrified of catching Drake and of returning to report failure; and we can be sure that the always vehement Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa let his views on their conduct be known. He already had the Viceroy’s ear, having done him signal if not too scrupulous service in the taking of the unfortunate Tupac Amaru (above, Ch. -

PORTS of CALL WORLDWIDE.Xlsx

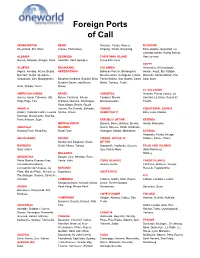

Foreign Ports of Call AFGHANISTAN BENIN Shantou, Tianjin, Xiamen, ECUADOR Kheyrabad, Shir Khan Cotnou, Porto-Novo Xingang, Yantai, Zhanjiang Esmeraoldas, Guayaquil, La Libertad, Manta, Puerto Bolivar, ALBANIA BERMUDA CHRISTMAS ISLAND San Lorenzo Durres, Sarande, Shegjin, Vlore Hamilton, Saint George’s Flying Fish Cove EGYPT ALGERIA BOSNIAAND COLOMBIA Alexandria, Al Ghardaqah, Algiers, Annaba, Arzew, Bejaia, HERZEGOVINA Bahia de Portete, Barranquilla, Aswan, Asyut, Bur Safajah, Beni Saf, Dellys, Djendjene, Buenaventura, Cartagena, Leticia, Damietta, Marsa Matruh, Port Ghazaouet, Jijel, Mostaganem, Bosanka Gradiska, Bosakni Brod, Puerto Bolivar, San Andres, Santa Said, Suez Bosanki Samac, and Brcko, Marta, Tumaco, Turbo Oran, Skikda, Tenes Orasje EL SALVADOR AMERICAN SAMOA BRAZIL COMOROS Acajutla, Puerto Cutuco, La Aunu’u, Auasi, Faleosao, Ofu, Belem, Fortaleza, Ikheus, Fomboni, Moroni, Libertad, La Union, Puerto El Pago Pago, Ta’u Imbituba, Manaus, Paranagua, Moutsamoudou Triunfo Porto Alegre, Recife, Rio de ANGOLA Janeiro, Rio Grande, Salvador, CONGO, EQUATORIAL GUINEA Ambriz, Cabinda, Lobito, Luanda Santos, Vitoria DEMOCRATIC Bata, Luba, Malabo Malongo, Mocamedes, Namibe, Porto Amboim, Soyo REPUBLIC OF THE ERITREA BRITISH VIRGIN Banana, Boma, Bukavu, Bumba, Assab, Massawa ANGUILLA ISLANDS Goma, Kalemie, Kindu, Kinshasa, Blowing Point, Road Bay Road Town Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka ESTONIA Haapsalu, Kunda, Muuga, ANTIGUAAND BRUNEI CONGO, REPUBLIC Paldiski, Parnu, Tallinn Bandar Seri Begawan, Kuala OF THE BARBUDA Belait, Muara, Tutong -

Patagonia Travel Guide

THE ESSENTIAL PATAGONIA TRAVEL GUIDE S EA T TLE . RIO D E J A NEIRO . BUENOS AIRES . LIMA . STUTTGART w w w.So u t h A mer i c a.t r av e l A WORD FROM THE FOUNDERS SouthAmerica.travel is proud of its energetic Team of travel experts. Our Travel Consultants come from around the world, have traveled extensively throughout South America and work “at the source" from our operations headquarters in Rio de Janeiro, Lima and Buenos Aires, and at our flagship office in Seattle. We are passionate about South America Travel, and we're happy to share with you our favorite Buenos Aires restaurants, our insider's tips for Machu Picchu, or our secret colonial gems of Brazil, and anything else you’re eager to know. The idea to create SouthAmerica.travel first came to Co-Founders Juergen Keller and Bradley Nehring while traveling through Brazil's Amazon Rainforest. The two noticed few international travelers, and those they did meet had struggled to arrange the trip by themselves. Expertise in custom travel planning to Brazil was scarce to nonexistent. This inspired the duo to start their own travel business to fill this void and help travelers plan great trips to Brazil, and later all South America. With five offices on three continents, as well as local telephone numbers in 88 countries worldwide, the SouthAmerica.travel Team has helped thousands of travelers fulfill their unique dream of discovering the marvelous and diverse continent of South America. Where will your dreams take you? Let's start planning now… “Our goal is to create memories that -

My Friend, the Volcano (Adapted from the 2004 Submarine Ring of Fire Expedition)

New Zealand American Submarine Ring of Fire 2007 My Friend, The Volcano (adapted from the 2004 Submarine Ring of Fire Expedition) FOCUS MAXIMUM NUMBER OF STUDENTS Ecological impacts of volcanism in the Mariana 30 and Kermadec Islands KEY WORDS GRADE LEVEL Ring of Fire 5-6 (Life Science/Earth Science) Asthenosphere Lithosphere FOCUS QUESTION Magma What are the ecological impacts of volcanic erup- Fault tions on tropical island arcs? Transform boundary Convergent boundary LEARNING OBJECTIVES Divergent boundary Students will be able to describe at least three Subduction beneficial impacts of volcanic activity on marine Tectonic plate ecosystems. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Students will be able to explain the overall tec- The Submarine Ring of Fire is an arc of active vol- tonic processes that cause volcanic activity along canoes that partially encircles the Pacific Ocean the Mariana Arc and Kermadec Arc. Basin, including the Kermadec and Mariana Islands in the western Pacific, the Aleutian Islands MATERIALS between the Pacific and Bering Sea, the Cascade Copies of “Marianas eruption killed Anatahan’s Mountains in western North America, and numer- corals,” one copy per student or student group ous volcanoes on the western coasts of Central (from http://www.cdnn.info/eco/e030920/e030920.html) America and South America. These volcanoes result from the motion of large pieces of the AUDIO/VISUAL MATERIALS Earth’s crust known as tectonic plates. None Tectonic plates are portions of the Earth’s outer TEACHING TIME crust (the lithosphere) about 5 km thick, as Two or three 45-minute class periods, plus time well as the upper 60 - 75 km of the underlying for student research mantle. -

Hut-To-Hut Trek in Patagonia Binational Park

HUT-TO-HUT TREK IN PATAGONIA BINATIONAL PARK Northern Patagonia, Chile & Argentina Duration 9 days / 8 nights Difficulty Advanced Departure November to March OVERVIEW A distinctive “northern” Patagonia experience visiting both Chile and Argentina via a “Hut to Hut” trek that is situated in some of the most remote terrain of the newly formed Patagonia Binational Park. The trail follows an old route once used by smugglers trafficking goods and animals between Argentina and Chile. The rustic huts are outfitted basecamps that allow for basic comfort, tucked away in beech forest in the enchanting El Zeballos and Chacabuco valleys. The Patagonia Park was a private reserve donated by the late Doug Tompkins and his wife Kris, and it is now part of the country’s national park system, known for its combination of cold steppe, wetlands, deciduous forests, and high mountain terrain. The trip includes a scenic drive along Chile’s famous Southern Highway, winding through breathtaking fjord land and emerald temperate rainforest. 01 PROGRAM: HUT-TO-HUT TREK IN PATAGONIA BINATIONAL PARK TRIP HIGHLIGHTS Explore the newly developed Patagonia Park, a major conservation project between Chile and Argentina. Discover the diversity of fauna in Patagonia, including huemul deer, pumas, guanaco, condors, rheas, flamingos and more. Spend several nights in a wood-hewn hut next to a warm fire, using the huts as a base to trek through wilderness not seen by many travelers. Enjoy a scenic ride along Chile’s most famous highway, the Carretera Austral. 02 PROGRAM: HUT-TO-HUT TREK IN PATAGONIA BINATIONAL PARK DAY-BY-DAY ITINERARY Day 4.