Keyboard Tablatures of the Mid-Seventeenth Century In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival 2018 Runs June 20-August 26 with 350+ Performances, Talks, Events, Exhibits, Classes & Works

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR IMAGES AND MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Nicole Tomasofsky, Public Relations and Publications Coordinator 413.243.9919 x132 [email protected] JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE FESTIVAL 2018 RUNS JUNE 20-AUGUST 26 WITH 350+ PERFORMANCES, TALKS, EVENTS, EXHIBITS, CLASSES & WORKSHOPS April 26, 2018 (Becket, MA)—Jacob’s Pillow announces the Festival 2018 complete schedule, encompassing over ten weeks packed with ticketed and free performances, pop-up performances, exhibits, talks, classes, films, and dance parties on its 220-acre site in the Berkshire Hills of Western Massachusetts. Jacob’s Pillow is the longest-running dance festival in the United States, a National Historic Landmark, and a National Meal of Arts recipient. Founded in 1933, the Pillow has recently added to its rich history by expanding into a year-round center for dance research and development. 2018 Season highlights include U.S. company debuts, world premieres, international artists, newly commissioned work, historic Festival connections, and the formal presentation of work developed through the organization’s growing residency program at the Pillow Lab. International artists will travel to Becket, Massachusetts, from Denmark, Israel, Belgium, Australia, France, Spain, and Scotland. Notably, representation from across the United States includes New York City, Minneapolis, Houston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Chicago, among others. “It has been such a thrill to invite artists to the Pillow Lab, welcome community members to our social dances, and have this sacred space for dance animated year-round. Now, we look forward to Festival 2018 where we invite audiences to experience the full spectrum of dance while delighting in the magical and historic place that is Jacob’s Pillow. -

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

Paul Gerhardt As a Hymn Writer and His Influence on English Hymnody

Paul Gerhardt as a Hymn Writer and his Influence on English Hymnody by Theodore Brown Hewitt About Paul Gerhardt as a Hymn Writer and his Influence on English Hymnody by Theodore Brown Hewitt Title: Paul Gerhardt as a Hymn Writer and his Influence on English Hymnody URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/hewitt/gerhardt.html Author(s): Hewitt, Theodore Brown Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: A literary study of Gerhardt©s hymns and English translations of them. First Published: 1918 Publication History: First Edition: Yale University Press, 1918; Second Edition: Concordia Publishing House, 1976 Print Basis: Concordia Publishing House, 1976, omitting material still under copyright. Source: New Haven: Yale University Press Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2002-09 Status: Profitable future work may include: ·(none under consideration) Editorial Comments: Orthography was edited to facilitate automated use: ·ThML markup (assuming HTML semantics of whitespace) ·Added hyperlinks to (original) translations by Winkworth and (possibly altered) translations by others, at CCEL. ·Added appendix including (possibly altered) translations from the Moravian Hymn Book, 1912; Hymnal and Order of Service, 1925; and Lutheran Hymnary, 1913, 1935. This allows access to all or parts of over 60 translated or adapted hymns. ·Added WWEC entries to authors and translators. Contributor(s): Stephen Hutcheson (Transcriber) Stephen Hutcheson (Formatter) LC Call no: BV330.G4H4 1918 LC Subjects: Practical theology Worship (Public and Private) Including the church year, Christian symbols, liturgy, prayer, hymnology Hymnology Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Preface. p. 2 Contents. p. 3 Bibliography. p. 5 Chronological Table. -

9/5/2011-4/21/2012. Letters from a Danceaturg. Neil Baldwin to Lori Katterhenry

9/5/2011-4/21/2012. Letters from a Danceaturg. Neil Baldwin to Lori Katterhenry. No.1 - September 5, 2011 Dear Lori: I am grateful to Ryoko Kudo, Maxine Steinman and our MSU dancers for opening the doors to the studio in Life Hall last week and welcoming me to sit in on three sessions of the setting of excerpts from There is a Time (1956) by Jose Limon. They worked on “Opening Circle,” “Plant and Reap,” “Mourn,” “Laugh and Dance,” and “Hate & War.” Reviewing and editing my on-site notes, I recalled a helpful observation by Doris Humphrey in The Art of Making Dances with regard to this work. She writes, “There is a Time states its thematic material in the opening section and builds all the rest of its many parts on variations of the same movements. Unfortunately, this escapes most people; what they see is a suite form, contrasted ideas of dramatic or lyric significance. This is because the eye is not sufficiently trained to remember movement themes, and will usually miss them completely.” Indeed, the fact that the original title of There is a Time was Variations on a Theme came through powerfully during these sessions. Ryoko’s precisely-planned and at the same time intuitively- executed method was the embodiment of Limon’s preliminary concept notes for the dance, when he said that “the community…form[s] a very close circle which pulsates symbolizing an ovum or womb in travail…[T]he large circle…symbolize[s] time – the great continuity – eternal, unbroken…without hurry and without end.” I was also mindful of a point that Carla Maxwell made in an interview with The New York Times ten years ago about classic modern dance: “What's indispensable is a consistent point of view that relates to the times,'' she said. -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

Download Program

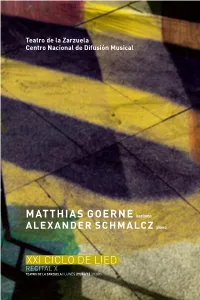

Teatro de la Zarzuela Centro Nacional de Difusión Musical MATTHIAS GOERNE barítono ALEXANDER SCHMALCZ piano XXI CICLO DE LIED RECITAL X TEATRO DE LA ZARZUELA | LUNES 29/06/15 20:00h Centro Nacional de Difusión Musical UNIVERSO BARROCO | Auditorio Nacional de Música UNIVERSO BARROCO | SAlA SINfónica 10/12/15 | ORQUESTA BARROCA DE HElSINKI 22/11/15 | 18:00h | ENSEMBlE MATHEUS AAPO HÄKKINEN clave y dirección | MATTHIAS JEAN-CHRISTOPHE SPINOSI director MONICA GROOP mezzosoprano MALENA ERNMAN Serse (mezzosoprano) Obras de Johan Helmich Roman, Joseph Martin Kraus, ADRIANA KUCˇEROVÁ Romilda (soprano) Johann Sebastian Bach y Joseph Haydn SONIA PRINA Arsamene (contralto) GOERNE barítono KERSTIN AVEMO Atalanta (soprano) 21/01/16 | HESPÈRION XXI MARINA DE LISO Amastre (mezzosoprano) JORDI SAVALL viola da gamba y dirección CHRISTIAN SENN Elviro (barítono) La Europa musical: 1500-1700 LUIGI DE DONATO Ariodate (bajo) Danzas italianas del renacimiento veneciano George Frideric Haendel (1685-1759): Serse, HW 40 Obras de John Dowland, Orlando Gibbons, William Brade, Luys de Milán, Antonio de Cabezón, Diego 14/12/15 | 19:30h | WIENER AKADEMIE ALEXANDER Ortiz, Samuel Scheidt, Joan Cabanilles, MARTIN HASElBÖCK director Henry Purcell, Guillaume Dumanoir, Antonio Valente SOPHIE KARTHÄUSER Susanna (soprano) y anónimos CARLOS MENA Joacim (contratenor) ALOIS MÜHLBACHER Daniel (contratenor) 25/02/16 | ACCADEMIA BIZANTINA SCHMALCZ piano MARIE-SOPHIE POLLAK Ayudante (soprano) OTTAVIO DANTONE clave y dirección PAUL SCHWEINESTER Primer anciano (tenor) Johann Sebastian -

The Use of Multiple Stops in Works for Solo Violin by Johann Paul Von

THE USE OF MULTIPLE STOPS IN WORKS FOR SOLO VIOLIN BY JOHANN PAUL VON WESTHOFF (1656-1705) AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO GERMAN POLYPHONIC WRITING FOR A SINGLE INSTRUMENT Beixi Gao, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2017 APPROVED: Julia Bushkova, Major Professor Paul Leenhouts, Committee Member Susan Dubois, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Gao, Beixi. The Use of Multiple Stops in Works for Solo Violin by Johann Paul Von Westhoff (1656-1705) and Its Relationship to German Polyphonic Writing for a Single Instrument. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2017, 32 pp., 19 musical examples, bibliography, 46 titles. Johann Paul von Westhoff's (1656-1705) solo violin works, consisting of Suite pour le violon sans basse continue published in 1683 and Six Suites for Violin Solo in 1696, feature extensive use of multiple stops, which represents a German polyphonic style of the seventeenth- century instrumental music. However, the Six Suites had escaped the public's attention for nearly three hundred years until its rediscovery by the musicologist Peter Várnai in the late twentieth century. This project focuses on polyphonic writing featured in the solo violin works by von Westhoff. In order to fully understand the stylistic traits of this less well-known collection, a brief summary of the composer, Johann Paul Westhoff, and an overview of the historical background of his time is included in this document. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study*

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 2 Number 2 Fall The mplicI ations of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study Desmond Hunter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Hunter, Desmond (1992) "The mpI lications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199205.02.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renaissance Keyboard Fingering The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study* Desmond Hunter The fingering of virginalist music has been discussed at length by various scholars.1 The topic has not been exhausted however; indeed, the views expressed and the conclusions drawn have all too frequently been based on limited evidence. I would like to offer some observations based on both a knowledge of the sources and the experience gained from applying the source fingerings in performances of the music. I propose to focus on two related aspects: the fingering of linear figuration and the fingering of graced notes. Our knowledge of English keyboard fingering is drawn from the information contained in virginalist sources. Fingerings scattered Revised version of a paper presented at the 25th Annual Conference of the Royal Musical Association in Cambridge University, April 1990. -

Zwischen Strengem Reglement Und Freier Entfaltung Die Ersten Kapellmeister Der Kurbrandenburgischen Hofkapelle in Der Zeit Vor Dem Dreißigjährigen Krieg

Kulturgeschichte Preuûens - Colloquien 3 (2016) Detlef Giese Zwischen strengem Reglement und freier Entfaltung Die ersten Kapellmeister der kurbrandenburgischen Hofkapelle in der Zeit vor dem Dreiûigjährigen Krieg Abstract Dass es vornehmlich die Kapellmeister sind, die einem Klangkörper Gesicht und Stimme geben, gilt für die Gegenwart gleichermaûen wie für die Geschichte. Der jeweilige Stelleninhaber ist einerseits eingebunden in seine vertraglichen Verpflichtungen, besitzt andererseits aber auch gewisse Freiheiten, im Rahmen bestimmter Möglichkeiten seinen Tätigkeitsbereich für sich selbst zu definieren. Die Erwartungshaltungen der wechselnden Dienstherren wandeln sich ebenso wie das politisch-gesellschaftliche, institutionelle und allgemein kulturelle Umfeld, in der die administrative und künstlerische Arbeit des Kapellmeisters angesiedelt ist. Die Wirkung und Ausstrahlungskraft, welche die Protagonisten hierbei entfalten, sind wichtige Gradmesser für die Bedeutung sowohl der Person als auch der Institution im regionalen wie überregionalen Maûstab. Für die Frühzeit der kurbrandenburgischen Hofkapelle sind zumindest die Namen einiger Kapellmeister überliefert, die als empirische Individualitäten fassbar werden. Dem ersten namentlich bekannte Amtsträger Johann Wesalius, der bereits in den 1570er Jahren an der Spitze des Ensembles stand, kommt in diesem Zusammenhang Aufmerksamkeit und Interesse zu, desgleichen Musikern wie Johannes Eccard und Nikolaus Zangius, die in den ersten beiden Jahrzehnten des 17. Jahrhunderts zu den respektablen, im Falle von Eccard sogar zu den prominenten, bis heute immer noch wertgeschätzten deutschen Komponisten ihrer Zeit zählten. Obwohl sie an jeweilige Rahmenbedingungen materieller wie personeller Art gebunden waren, besaûen sie doch ausreichend Räume zur eigenen Entfaltung, um sich künstlerisch zu profilieren. Auf der anderen Seite steht eine strenge Reglementierungen der Aufgaben und Aktivitäten von Seiten der Regenten, die nicht selten einengend wirkten, zumal die Ressourcen über den betrachteten Zeitraum von 1570 bis ca. -

Download Booklet

572433bk Byrd EU_572433bk Byrd 21/07/2011 12:10 Page 4 notes, sometimes in two strands at once, against arrangement in Nevell. The noble final theme – the same counterpoints that seem a throwback to an earlier as that of the finest fugue in The Well-Tempered Clavier William generation. For that reason, most authorities consider – appears in doubled note values, wrought in Byrd’s this a youthful effort, but there is mastery here that goes most mature style. Here is what I think: this is Byrd’s far beyond Byrd’s early cantus firmus exercises in the memorial for Mary, Queen of Scots, and the BYRD style of Tallis and Blitheman. The notation in quarter- augmentation at the end is the prolongation of her line note (crotchet) beats, the division into clearly separated with her son James I, the ancestor of all subsequent variations, and the unique late source all point to this British monarchs.! Complete Fantasias for Harpsichord being the last of the fantasias!– Byrd, perhaps on a Byrd addressed a plea for careful execution of his winter’s night at Stondon Place, indulging in nostalgia works to “all true lovers of Musicke”, which closes thus: for the improvisational ecstasies of times past. “As I have done my best endeavor to give you content, so Glen Wilson The other hexachord piece # is the most modest I beseech you satisfie my desire in hearing them well and playful of the set. The theme in long single notes is expressed: and then I doubt not, for Art and Ayre both of to be played from beginning to end in the treble by a skillful and ignorant they will deserve liking. -

Heritage Hymn of the Month JANUARY 1

Heritage Hymn of the Month In Jesus’ Name JANUARY 1. In Jesus’ name Our work must all be done “In Jesus’ Name” If it shall compass our true good and aim, ELH 4 And not end in shame alone; For ev’ry deed “And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of Which in it doth proceed, the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through Him” Success and blessing gains (Colossians 3:17, ESV). It is important to begin in the name of Jesus. Till it the goal attains. The Norwegian immigrants used this hymn at the beginning of Thus we honor God on high important endeavors – emigrating to America, building their homes, And ourselves are blessed thereby; starting churches and schools. It was in every Norwegian and Danish Wherein our true good remains. hymnal from the time it was first published in 1645, and often was the first hymn in the book. This is a good hymn for the New Year, and as 2. In Jesus’ name we emphasize Christian education and missions. We praise our God on high, He blesses them who spread abroad His fame, The three stanzas can be remembered from the first two lines in each. And we do His will thereby. “In Jesus’ name/Our work must all be done” – serving in our vocations E’er hath the Lord not for our self-interest, but in Jesus’ name. “In Jesus’ name/We praise Done great things by His Word, our God on high” – as we “spread abroad His fame” in missions, And still doth bare His arm remembering that it is not our burden but the Lord who does “great His wonders to perform; things by His Word.” To conclude: “In Jesus’ name/We live and we Hence we should in ev’ry clime will die” – for to live is Christ and to die is gain.