River Axe, Weycroft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seaton Wetlands Sidmouth Seaton

How to find us © CROWN COPYRIGHT DATABASE RIGHTS 2012 ORDNANCE SURVEY 100023746 ORDNANCE SURVEY RIGHTS 2012 COPYRIGHT DATABASE © CROWN Lyme Regis Colyford Axe Estuary Axe Estuary WETLANDS WETLANDS A3052 Seaton Wetlands Sidmouth Seaton Seaton Road Wetlands Information Axe Estuary ENTRANCE Seaton Cemetery WETLANDS ◊ Free parking River Axe ◊ Toilets (including disabled toilet and baby changing) ◊ 5 bird hides Seaton Wetlands is located six miles west of ◊ Tramper off-road mobility scooter hire Lyme Regis and eight miles east of Sidmouth, ◊ Discovery hut between Colyford and Seaton. ◊ Picnic area In the middle of Colyford village on the A3052, take the Seaton road, signposted Axe Vale Static ◊ No dogs except assistance dogs Caravan Park. After half a mile turn left into ◊ Refreshments at weekends Seaton cemetery and continue through the ◊ Cycling welcomed on most of site cemetery car park to the Wetlands parking area. ◊ Wheelchair and buggy friendly paths ◊ Pond dipping equipment for hire Contact the countryside team: East Devon District Council ◊ Nearly 4 miles of trails/boardwalks Knowle Sidmouth EX10 8HL Tel: 01395 517557 Email: [email protected] www.eastdevon.gov.uk /eastdevoncountryside X2002 East Devon – an outstanding place Lyme Regis Colyford welcome to seaton wetlands N Swan Hill Road Sidmouth Entrance Popes Lane 1 Tram line Tram path Wheelchair friendly Footpath Colyford Seaton Road Common Hide 1 Water body Water Reserve Nature bed Reed colyford common Tidal salt marsh with broadwalk access to hide, viewing WC 2 platform and circular reedbed walk. Bus stop allowed Cyclists flooded area Seasonally Island Hide 3 Cemetery Entrance Marsh Lane Tower Hide Colyford Road Colyford 2 stafford marsh River Axe Ponds, reeds and the Stafford Brook make up the learning zone and wildlife garden. -

River Axe Draft Restoration Plan

Restoring the River Axe Site of Special Scientific Interest and Special Area of Conservation River Restoration Plan Draft for comment - 7 December 2015 to 17 January 2016 CONTENTS Chapter Page Executive Summary 1 Aim of the restoration plan 1 Working with others 2 How to comment on the draft plan 3 Delivering the restoration plan 3 1 Restoration of the River Axe 5 1.1 Introduction 5 1.2 The need for restoration 7 1.3 A restoration vision 7 1.4 How can we deliver this restoration? 8 1.5 Our approach 8 1.6 How to use this plan 10 1.7 Who is this plan for? 11 2 The River Axe Site of Special Scientific Interest 12 2.1 Geology and hydrology 12 2.2 Ecology 13 2.3 Conservation objectives for the River Axe SSSI 13 2.4 Condition of the River Axe SSSI 14 2.5 Water Framework Directive objectives 16 2.6 Land use and land use change 17 2.7 Water quality 17 2.8 Flood risk 18 2.9 Invasive non-native species and disease 19 2.10 Influences on geomorphology and channel change 20 3 River sector descriptions 23 3.1 Summary of sector descriptions 23 3.2 Upper sector 25 3.2.1 Physical characteristics 26 3.2.2 Historical change 26 3.2.3 Geomorphological behaviour 27 3.2.4 Significant issues 27 3.3 Mid sector 29 3.3.1 Physical characteristics 30 3.3.2 Historical change 30 3.3.3 Geomorphological behaviour 31 3.3.4 Significant issues 31 3.4 Lower sector 33 3.4.1 Physical characteristics 35 3.4.2 Historical change 35 3.4.3 Geomorphological behaviour 36 3.4.4 Significant issues 36 DRAFT FOR COMMENT 4 Channel modifications and restoration measures 38 4.1 Geomorphology -

South West River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment

South West river basin district Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment March 2016 Executive summary The Flood Risk Management Plan (FRMP) for the South West River Basin District (RBD) provides an overview of the range of flood risks from different sources across the 9 catchments of the RBD. The RBD catchments are defined in the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) and based on the natural configuration of bodies of water (rivers, estuaries, lakes etc.). The FRMP provides a range of objectives and programmes of measures identified to address risks from all flood sources. These are drawn from the many risk management authority plans already in place but also include a range of further strategic developments for the FRMP ‘cycle’ period of 2015 to 2021. The total numbers of measures for the South West RBD FRMP are reported under the following types of flood management action: Types of flood management measures % of RBD measures Prevention – e.g. land use policy, relocating people at risk etc. 21 % Protection – e.g. various forms of asset or property-based protection 54% Preparedness – e.g. awareness raising, forecasting and warnings 21% Recovery and review – e.g. the ‘after care’ from flood events 1% Other – any actions not able to be categorised yet 3% The purpose of the HRA is to report on the likely effects of the FRMP on the network of sites that are internationally designated for nature conservation (European sites), and the HRA has been carried out at the level of detail of the plan. Many measures do not have any expected physical effects on the ground, and have been screened out of consideration including most of the measures under the categories of Prevention, Preparedness, Recovery and Review. -

People Property Places

Stotehayes Membury, Honiton, Devon People Property Places A quintessential stone and thatched Devon cottage dating back to the fourteenth century and being Listed Grade II, set within beautiful countryside with fishing rights on the River Yarty. Features • Entrance Porch • Flagstone Hall • Drawing Room • Sitting Room with Inglenook • Well Fitted Kitchen / Breakfast Room with Aga • Cloakroom • Utility Room • Principal En Suite Bedroom • Three Further Bedrooms • Family Bathroom • Thatched Linhay • Summerhouse / Garden Room • Double Garage • Delightful Gardens • Paddock • Riverside Meadow • Three Quarters of a Mile of Single and Double Bank Fishing on the Yarty River • In all about 2.39 hectares (5.905 acres) The Location Stotehayes occupies a delightful country setting, within the Yarty Valley which is considered by many to be one of the most beautiful areas in East Devon, where the landscape has remained unchanged for centuries. Whilst quiet and secluded, glorious views are enjoyed from all areas of the gardens and house making this a very special property. The village of Stockland is within easy reach with its highly respected primary school, playing fields, church, village hall and thriving tennis club. Membury , a couple of miles away, has an Award Winning Post Office / Store, village hall and a church. For day-to-day amenities both Axminster and Chard are easily accessible, Axminster also having the well-known Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall ‘s ‘River Cottage Canteen & Deli’ and there is a good Tesco store in Chard. There is also an excellent Farm Shop at Kilmington. Honiton is in the opposite direction towards Exeter and is famous for its long, wide high street with specialist shops as well as the more well-known stores. -

South West River Basin Management Plan, Including Local Development Documents and Sustainable Community Strategies (Local Authorities)

River Basin Management Plan South West River Basin District Contact us You can contact us in any of these ways: • email at [email protected] • phone on 08708 506506 • post to Environment Agency (South West Region), Manley House, Kestrel Way, Exeter EX2 7LQ The Environment Agency website holds the river basin management plans for England and Wales, and a range of other information about the environment, river basin management planning and the Water Framework Directive. www.environment-agency.gov.uk/wfd You can search maps for information related to this plan by using ‘What’s In Your Backyard’. http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/maps SW River Basin Management Plan Erratum The following changes were made to this document in January 2011. Table 1 updated to reflect reduction by two in number of heavily modified river water bodies and increase by two in number of natural river water bodies. Figure 15 for Tamar catchment updated to reflect change in two river water bodies from heavily modified to natural (see erratum sheet in Annex B for water body specific details). Published by: Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD tel: 08708 506506 email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency Some of the information used on the maps was created using information supplied by the Geological Survey and/or the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and/or the UK Hydrographic Office All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior -

K – Water Framework Directive Assessment Report

Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Appendix K ––– Water Framework Directive Assessment South Devon and DoDoDorsetDo rset Coastal AAAdvisoryAdvisory Group ((SDADSDADSDADCAGCAGCAG)))) Shoreline Management Plan Review ((SMP2SMP2SMP2)))) Durlston Head to Rame Head Appendix K – Water Framework Directive Assessment Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Appendix K ––– Water Framework Directive Assessment The Supporting Appendices These appendices and the accompanying documents provide all of the information required to support the Shoreline Management Plan. This is to ensure that there is clarity in the decision-making process and that the rationale behind the policies being promoted is both transparent and auditable. The appendices are: A: SMP Development This reports the history of development of the SMP, describing more fully the plan and policy decision-making process. B: Stakeholder Engagement All communications from the stakeholder process are provided here, together with information arising from the consultation process. C: Baseline Process Understanding Includes baseline process report, defence assessment, NAI and WPM assessments and summarises data used in assessments. D: SEA Environmental Baseline This report identifies and evaluates the environmental features Report (Theme Review) (human, natural, historical and landscape). E: Issues & Objectives Evaluation Provides information on the issues and objectives identified as part of the Plan development, including appraisal of their importance. F: Initial Policy Appraisal & Scenario Presents the consideration of generic policy options for each frontage, Development identifying possible acceptable policies, and their combination into ‘scenarios’ for testing. Also presents the appraisal of impacts upon shoreline evolution and the appraisal of objective achievement. G: Preferred Policy Scenario Testing Presents the policy assessment and appraisal of objective achievement towards definition of the Preferred Plan (as presented in the Shoreline Management Plan document). -

Cc100712cba Severe Weather Event 7Th July 2012

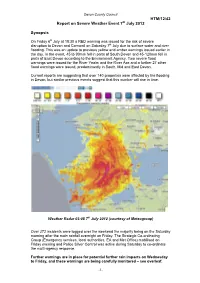

Devon County Council HTM/12/42 Report on Severe Weather Event 7 th July 2012 Synopsis On Friday 6 th July at 18:30 a RED warning was issued for the risk of severe disruption to Devon and Cornwall on Saturday 7 th July due to surface water and river flooding. This was an update to previous yellow and amber warnings issued earlier in the day. In the event, 45 to 90mm fell in parts of South Devon and 45-120mm fell in parts of East Devon according to the Environment Agency. Two severe flood warnings were issued for the River Yealm and the River Axe and a further 27 other flood warnings were issued, predominantly in South, Mid and East Devon. Current reports are suggesting that over 140 properties were affected by the flooding in Devon, but similar previous events suggest that this number will rise in time. Weather Radar 03:05 7 th July 2012 (courtesy of Meteogroup) Over 272 incidents were logged over the weekend the majority being on the Saturday morning after the main rainfall overnight on Friday. The Strategic Co-ordinating Group (Emergency services, local authorities, EA and Met Office) mobilised on Friday evening and Police Silver Control was active during Saturday to co-ordinate the multi-agency response. Further warnings are in place for potential further rain impacts on Wednesday to Friday, and these warnings are being carefully monitored – see overleaf. -1- Devon County Council DCC’s Flood Risk Management, Highways and Emergency Planning Teams are working closely with the District Councils and the Environment Agency to coordinate a full response. -

Download Annex A

Landscape Character Assessment in the Blackdown Hills AONB Landscape character describes the qualities and features that make a place distinctive. It can represent an area larger than the AONB or focus on a very specific location. The Blackdown Hills AONB displays a variety of landscape character within a relatively small, distinct area. These local variations in character within the AONB’s landscape are articulated through the Devon-wide Landscape Character Assessment (LCA), which describes the variations in character between different areas and types of landscape in the county and covers the entire AONB. www.devon.gov.uk/planning/planning-policies/landscape/devons-landscape-character- assessment What information does the Devon LCA contain? Devon has been divided into unique geographical areas sharing similar character and recognisable at different scales: 7 National Character Areas, broadly similar areas of landscape defined at a national scale by Natural England and named to an area recognisable on a national scale, for example, ‘Blackdowns’ and ‘Dartmoor’. There are 159 National Character Areas (NCA) in England; except for a very small area in the far west which falls into the Devon Redlands NCA, the Blackdown Hills AONB is within Blackdowns NCA. Further details: www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-character-area-profiles-data-for-local- decision-making/national-character-area-profiles#ncas-in-south-west-england 68 Devon Character Areas, unique, geographically-specific areas of landscape. Each Devon Character Area has an individual identity, but most comprise several different Landscape Character Types. Devon Character Areas are called by a specific place name, for example, ‘Blackdown Hills Scarp’ and ‘Axe Valley’. -

Remembering the Men of Buckland St Mary Who Fought in WWI

Buckland St Mary Mary Buckland St who fought in WWI Remembering the men of Vanished Lives Vanished VANISHED LIVES ROSANNA BARTON BUCKLAND ST MARY PARISH COUNCIL Futility In Memory Of The Brave Men Move him into the sun— Gently its touch awoke him once, Of Buckland St Mary At home, whispering of fields half-sown. Who Gave Their Lives Always it woke him, even in France, In The Great War Until this morning and this snow. 1914-1919 If anything might rouse him now The kind old sun will know. Think how it wakes the seeds— Woke once the clays of a cold star. Are limbs, so dear-achieved, are sides Full-nerved, still warm, too hard to stir? Was it for this the clay grew tall? —O what made fatuous sunbeams toil To break earth’s sleep at all? Wilfred Owen Base of the War Memorial in Buckland St Mary churchyard ‘From Buckland St Mary there went into HM’s forces about seventy men from a population of about 450. Of these sixteen joined voluntarily all the remainder, except those underage at the time attested under Lord Derby’s scheme …1 … On the outbreak of war several ladies of the village took a course of sick nursing and ambulance work and being thus qualified they did most useful work at the V.A.D.2 hospital at Ilminster. The women of the parish were organised by Mesdames Lance and Pott and met weekly for the purpose of making pillowcases and moss bags for splints, several hundred of which, were sent to a collection station.’ (The Western Gazette) 1 See page 7. -

Membury Parish Council Draft Neighbourhood Plan 2016 − 2031

Membury Parish Council Draft Neighbourhood Plan 2016 − 2031 Draft version 3.35.7 March 2016 Draft 3.35.7 − March 2016 1 Vision, Aims and Objectives Our Vision for the parish represents our view of what we would like the parish to be like in the future by the time that the Plan reaches its end date in 2031. The Vision is a representation of the Aims of our Plan, the things we would like to achieve, which have been derived from local community consultation and other evidence. Membury Neighbourhood Plan Vision Statement TO MAINTAIN AND ENHANCE THE UNIQUE CHARACTER AND SENSE OF COMMUNITY WITHIN MEMBURY PARISH WHILST PERMITTING SMALL SCALE SUSTAINABLE GROWTH THAT IS IN LINE WITH THE NEEDS AND WISHES OF THE COMMUNITY. Our Aims The Aims of our Plan have been set following extensive community consultation and discussion. They are set out under a set of topic areas. These topics are: • Natural Environment • Built and Historic Environment • Housing and Population • Community Facilities and Services • Flooding • Transport and Access • Economy and Employment • Energy and Low Carbon Our Objectives Our Objectives (how we are going to achieve the Aims) are set out in each topic section in the Plan and it is from these Objectives that our policies and community actions have been developed. Appendices 1. Summary table of our Aims, Objectives, Policies and Community Actions 2. Membury Design Statement and Supplementary Planning Guidance 3. Blackdown Hills AONB Design Guide for Houses 4. Membury Housing Specific Questionnaire 5. Membury and Rock Flooding history and data source 2 Draft 3.35.7 − March 2016 Natural Environment Aim 1 Protect and enhance the natural environment, including the distinctive landscape and ecology. -

The Evolution of the Rivers of East Devon and South Somerset, UK

R.W. Gallois THE EVOLUTION OF THE RIVERS OF EAST DEVON AND SOUTH SOMERSET , UK R.W.G ALLOIS Gallois, R.W. 2006. The evolution of the rivers of east Devon and south Somerset, UK. Geoscience in south-west England, 11 , 205-213. With the exception of the River Tone, which appears to have been separated at an early stage from its neighbours to the south by a major fault, the rivers of south Somerset and east Devon were initiated on a southward dipping Tertiary planation surface. The evolutionary histories of the present-day catchments of the rivers Exe and Otter are complex and inter-related. Those of the adjacent Axe and Teign appear to be less complex and may have evolved relatively independently from the Exe-Otter system. The differences in the histories of the catchments are most clearly demonstrated by their terrace systems. The Exe-Otter catchment has 10 or more terrace levels at heights of up to 140 m above the modern floodplain. In contrast, the Axe, Teign and Tone catchments contain only one or two terrace levels all of which are less than 20 m above the present-day valley floor. The explanation suggested here for the difference involves a sequence of river captures that changed the forerunner of the present-day Otter from a major river capable of producing a 3-km wide gravelly braidplain into a minor stream. 92 Stoke Valley Road, Exeter, EX4 5ER, U.K. (E-mail: [email protected]). INTRODUCTION The middle and lower reaches of the River Exe and the There are too few age data to determine the period of time adjacent catchments of the Axe, Otter, Teign and Tone drain an during which the terrace sequences in south-west England area with a complex topographical relief that ranges from over evolved, but comparison with the denudation chronology of 300 m above Ordnance Datum (O.D.) in the Blackdown Hills southern England as a whole suggests that all the terraces to a few metres above O.D. -

Directions to Furley Cottages

Directions to Furley Cottages Furley Cottages, Goodmans House, Membury, Axminster. EX13 7TU 01404 881447 Sat Nav: N 50 50 26.4, W 03 02 17.8 or N 50 50.440, W 03 02.297 What3Words https://w3w.co/worlds.workflow.merchant We hope the following may be helpful ................ Goodmans House & Furley Cottages are on “Casehayes Lane” and the postcode is EX13 7TU. Although there are many different ways of getting here, there are some roads in the local area which are only suitable for agricultural vehicles, so our directions offer the most practical and straightforward route. If you are arriving via the A30 – your SatNav may suggest a turn left off the road after James Lane or the Ferne Animal Sanctuary. This lane is signed to Godworthy Farm. Don’t. Just before the junction at Furley, your SatNav may suggest a sharp left turn into a very narrow lane. Again don’t. It may be a good idea to check the route on Google Maps and familiarise yourself where we are located prior to setting off. Depending on the time of year, the lanes can seem narrower than they actually are, as the farmers are not permitted to cut the hedges at certain times of year. Be prepared to reverse if you encounter farm vehicles as some are unable to reverse. Take your time, we live at a different pace here and no one will rush you. You may encounter wildlife on the lanes, again take your time they will go in the hedges, eventually! From the Midlands and the North.