Hanford Cleanup: the First 20 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festive Funnies

December 14 - 20, 2019 Festive Funnies www.southernheatingandac.biz/ Homer from “The Simpsons” $10.00 OFF any service call one per customer. 910-738-70002105-A EAST ELIZABETHTOWN RD CARDINAL HEART AND VASCULAR PLLC Suriya Jayawardena MD. FACC. FSCAI Board Certified Physician Heart Disease, Leg Pain due to poor circulation, Varicose Veins, Obesity, Erectile Dysfunction and Allergy clinic. All insurances accepted. Same week appointments. Friendly Staff. Testing done in the same office. Plan for Healthy Life Style 4380 Fayetteville Rd. • Lumberton, NC 28358 Tele: 919-718-0414 • Fax: 919-718-0280 • Hours of Operation: 8am-5pm Monday-Friday Page 2 — Saturday, December 14, 2019 — The Robesonian ‘The Simpsons,’ ‘Bless the Harts,’ ‘Bob’s Burgers’ and ‘Family Guy’ air Christmas Specials By Breanna Henry “The Simpsons” is known for must be tracked down if there is overall, and having to follow a se- job at a post office. However, Lin- recognize the “Game of Thrones” TV Media its celebrity guest voices (many to be any hope of saving Christ- ries with 672 episodes (and a da discovers an undelivered pack- reference in this episode title, a celebs lend their own voices to a mas. In completely unrelated movie) under its belt might seem age and ends up going a little off- spin on the Stark family slogan uddle up for a festive, fun- storyline that’s making fun of news, this year’s Springfield Mall difficult if it weren’t for how book to ensure it reaches its in- “Winter is Coming.” Cfilled night on Fox, when the them). A special episode is the Santa is none other than famed much heart “Bless the Harts” has tended destination. -

Politics Core SPARTANS@I DERAT Wcnlom STATE UNIWSITT 2005

Politics Core SPARTANS@I DERAT wcnlom STATE UNIWSITT 2005 1NC Shells Links, Continued Bush Good - Energy Bill 3-5 Guantanamo Bay Bush Bad - Energy Bill 6-7 Bush Good - Partisan Uniqueness Bush Good - Tom Delay Energy Bill Will Pass Bush Bad Will Pass 8 Bush Bad - Specter AT: MTBE Blocks 9 Bush Bad - A2: GOP Lx AT: Won't Pass - Court Battle 10 Other Links Energy Bill Won't Include ANWR 11 Korematsu - Bush Bad Energy Bill Won't Pass Oversight Board - Bush Bad Won't Pass 12 Oversight Board - Bush Good Won't Pass - No MTBE Compromise 13 Carnivore - Bush Bad Generic Links Extraordinary Rendition - Bush Bad Bush Good Workplace Drug Testing - Bush Good 2NC 14 Courts Links - Bush Good Generic Bush Good 2NC 15 Agency Links - General Ext. Partisanship 16 Internal Links A2: Public Popularity 17 Political Capital Bush Bad Political Capital KeyIFinite Ext: Concession 18 A2: Political Capital Public 2NC 19 WinnersILosers Specific Links Losers Lose PATRIOT Act Winners Win Bush Bad 1NC 20 A2: Winners Win Bush Bad - Bipart 2 1 GOP and Democrats Bush Bad - Dems 22 Moderate GOP Key A2: GOP Backlash 23 GOP Base Key Bush Good - Loss 24 GOP Unity Key Bush Good - General 2 5 Democrats Key Racial Profiling Concessions Bush Bad - 1NC 2 6 A2: Concessions Bad Bush Bad - 2NC 2 7 A2: Concessions Ext; Bush Bad - Win 28 Flip Flop Ext: Bush Bad - Dems 2 9 Flip Flops Kill Agenda Bush Good - 1 NC 30 A2: Flip Flops Bush Good - 2NC 3 1 Focus Immigration Focus Key Bush Good 1NC A2: Focus Bush good - Political Capital Popularity Bush Good - GOP Backlash Popularity Key Bush -

Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I

Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4 - 7, 2002 Richland, WA FINAL REPORT A Collaborative Workshop: United States Fish & Wildlife Service The Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN) Hanford Reach National Monument 1 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group in collaboration with the United States Fish & Wildlife Service. CBSG. 2002. Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I. FINAL REPORT. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. 2 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4-7, 2002 Richland, WA TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1. Executive Summary 1 A. Introduction and Workshop Process B. Draft Vision C. Draft Goals 2. Understanding the Past 11 A. Personal, Local and National Timelines B. Timeline Summary Reports 3. Focus on the Present 31 A. Prouds and Sorries 4. Exploring the Future 39 A. An Ideal Future for Hanford Reach National Monument B. Goals Appendix I: Plenary Notes 67 Appendix II: Participant Introduction questions 79 Appendix III: List of Participants 87 Appendix IV: Workshop Invitation and Invitation List 93 Appendix V: About CBSG 103 Hanford Reach National Monument 3 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 4 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4-7, 2002 Richland, WA Section 1 Executive Summary Hanford Reach National Monument 5 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 6 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Executive Summary A. Introduction and Workshop Process Introduction to Comprehensive Conservation Planning This workshop is the first of three designed to contribute to the Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) of Hanford Reach National Monument. -

Sí Hay Tecnología Para Tratar Basura

Toma posesión Solicita Calderón Austria es a la gente: nuevo director SUPERADO de API Manzanillo DenuncIen A por Alemania DIARIO DE MANZANILLO delIncuenTes NACIONAL 10-A DEPORTES 1-C www.diariodecolima.com Colima, CoIima. Martes 17 de Junio de 2008 Año 55. No. 18,303 $5.00 RIESGO Las huellas de rodamiento de la avenida Ignacio Sandoval, en la zona norte de esta capital, representan un peligro para los automovilistas, pues el concreto tiene un marcado desnivel. A esto se agrega la mala iluminación, piedras sueltas y baches que existen en esta arteria vial. (Foto Horacio Medina) En México ¿A DÓNDE VA LA BASURA? Armería (El Campanario) Regularización aprobada Sí hay tecnología Villa de Álvarez Contempla clausura Cuauhtémoc (Cerro Colorado) para tratar basura Clausurado Semarnat: Ningún funcionario de Colima asistió a presentación de diver- Ixtlahuacán (San Gabriel) sos proyectos Regularizado Hugo RAMÍREZ PULIDO los diferentes proyectos de plan- para conocer el funcionamiento conviene”. tas de residuos sólidos, al cual no de una planta de tratamiento de Dijo que se tendrá que ser Manzanillo (Tapeixtles) El delegado de la Semarnat, Raúl asistió ningún funcionario estatal residuos sólidos. muy cuidadoso en ese aspecto, Arredondo Nava, afirmó que de Colima. Arredondo comentó que para ya que otras ciudades han tenido Realiza obras complementarias para tener mayores márgenes de México cuenta con la tecnología Tengo la información con ese tipo de plantas, Banobras ha malas experiencias al realizar eficiencia. necesaria aplicable a plantas de todas las propuestas, “hay ejem- ofrecido recursos a fondo perdi- estos procesos. tratamiento de residuos sólidos, plos de plantas que están funcio- do, “el proyecto lo paga la misma “En ocasiones los han dejado que se podría adaptar a las nece- nando, que podemos ver lo que institución cuando se solicita el con el producto sin procesar y han Minatitlán (Las Villas) sidades en la entidad. -

A New Land-Grant Mission for the 21St Century

ASPB News THE NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANT BIOLOGISTS Volume 37, Number 6 November/December 2010 President’s Letter Inside This Issue A New Land-Grant Mission for the 21st Century New Officers/Committees As I begin my term as president, I growth curve at which instabilities in Assume Posts express my appreciation for the op- food and energy security mount as portunity to serve the one society that resources of arable land and adequate Call for 2011 ASPB Award Nominations has molded my entire professional fresh water diminish. We are on a career. Over my 35 years as a member trajectory to reach 9 billion people Teaching Tools Featured of ASPB, I’ve seen the Society become a by 2030, increasing food, water, and at FESPB Congress truly global community that promotes energy demand by at least 50%, with- Call for Applications: SURF and serves plant biology research: out considering aggravating factors almost one-half of our membership of climate change, increased urban- currently resides outside the United ization, and increased demand from States. I also thank my immediate two Nick Carpita developing countries to attain Western predecessors, Tuan-hua David Ho and standards of living. Sally Assmann, for their superb job in strengthen- Developed countries have brought these issues ing focus on the role ASPB continues to play in into political focus as a basis of establishing new the globalization of plant biology. Together they funding priorities for the research needed to meet provided guidance for the formation last year of unprecedented needs. Not only is it a moral impera- the Global Plant Council (GPC), a new partnership tive for the most prosperous countries of the world of plant societies spanning six continents. -

March 29, 2008 the Free-Content News Source That You Can Write! Page 1

March 29, 2008 The free-content news source that you can write! Page 1 Top Stories Wikipedia Current Events Governor of Puerto Rico Popular soap opera 'The •Eamon Sullivan (Australia) indicted in campaign finance Young and the Restless' breaks the 50m Freestyle World probe celebrates 35 years on the air Record, his time 21.28 seconds. Aníbal Acevedo Vilá, the Governor Wikinews interviews of the Commonwealth of Puerto three actresses of Zimbabwe prepares for Rico, was indicted the popular U.S. election with 19 counts daytime soap opera A parliamentary election will be related to The Young and the held in Zimbabwe tomorrow, along irregularities found Restless to commemorate the with a presidential election on the in the financing of serial's 35th anniversary, which same day. The election is for both his campaigns for was celebrated Wednesday. the House of Assembly and the public offices on Actresses Melody Thomas Scott, Senate. Voice of America has and off the island. Michelle Stafford, and Tricia Cast reported that analysts in took part in the largest Wikinews Zimbabwe have predicted a victory United States Army suspends interview to date. for Robert Mugabe. ammo contract for Afghan security forces Wikipedia Current Events With the last parliamentary The United States Army has Dwain Chambers: BBC, Sky election having been held in 2005, suspended their nearly $300 Sports & The Sun newspaper are the subsequent election was million contract with a Miami- all carrying reports that initially planned to be held in based company run by a 22 year- Chambers is to announce he is to 2010, but after an abortive plan to old that delivered old and become an English rugby league delay the 2008 presidential corroding ammunition from China player with Castleford Tigers. -

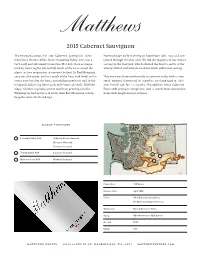

Cabernet Sauvignon

���� Cabernet Sauvignon The vineyard sources for our Cabernet Sauvignon come Harvest began early morning on September 10th, 2015 and con- from three distinct AVAs. In the Columbia Valley, 2015 was a tinued through October 20th. We did the majority of our cluster very early and extremely warm year. Hot days were accompa- sorting in the vineyard, which allowed the fruit to arrive at the nied by warm nights, but luckily much of the heat caused the winery chilled and without need for much additional sorting. plants to slow respiration to survive the heat. In Red Mountain, 2015 was also warm, and as a result of the heat, acid levels in the This wine was fermented mostly in concrete tanks with a very wines were low, but the heat created photosynthetic stall in the small amount fermented in stainless steel and aged in 80% vineyards, balancing lower acids with lower alcohols. Wahluke new French oak for 21 months. The addition of 6% Cabernet Slope, which is typically a more moderate growing area for Franc adds aromatic complexity and a touch dryer tannin that Washington, had better acid levels than Red Mountain to help helps with length and persistence. keep the wines fresh and ripe. CANADA ������ ��������� Bellingham Port Angeles 1 Columbia Valley AVA Stillwater Creek Vineyard, LAKE CHELAN I Woodinville COLUMBIA VALLEY Seattle D Dionysus Vineyard, Spokane A Wenatchee Bacchus Vineyard H OLYMPICS ANCIENT LAKES O Olympia CASCADES 2 Red Mountain AVA Canyons Vineyard NACHES HEIGHTS WAHLUKE SLOPE 3 Pullman Yakima LEWIS-CLARK SNIPES MOUNTAIN 1 VALLEY RATTLESNAKE HILLS RED MOUNTAIN 3 Wahluke Slope AVA Weinbau Vineyard Prosser Tri-Cities YAKIMA VALLEY 2 WALLA WALLA HORSE Walla Walla VALLEY HEAVEN HILLS COLUMBIA GORGE OREGON PACIFIC OCEAN PACIFIC Vancouver Portland N W E S Production 235 Cases Release Date April 2018 Blend 86% Cabernet Sauvignon, 8% Merlot, 6% Cabernet Franc Vinification Mostly Concrete Tanks Aging 80% New French Oak Barrels Alcohol 14.1% Retail $57 �������� ������ ����� ����� �� ��, �����������, �� ����� ��������������.���. -

G20070600/Ltr-07-0569/Edats

EDO Principal Correspondence Control FROM: DUE: / / EDO CONTROL: G20070600 DOC DT: 08/16/07 FINAL REPLY: Samuel W. Bodman, DOE TO: Chairman Klein FOR SIGNATURE OF : ** GRN ** CRC NO: 07-0569 DESC: ROUTING: Intelligence Program at DOE - Safeguarding Reyes (EDATS: SECY-2007-0301) Virgilio Kane Ash Ordaz Cyr/Burns DATE: 08/30/07 Hagan, ADM Sheron, RES ASSIGNED TO: CONTACT: Dyer, NRR Weber, NMSS NSIR Zimmerman Laufer, OEDO SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS OR REMARKS: For Appropriate Action. EDATS Number: SECY-2007-0301 Source: SECY GeealIfrmto Assigned To: NSIR OEDO Due Date: NONE Other Assignees: SECY Due Date: NONE Subject: Intelligence Program at DOE - Safeguarding Description: CC Routing: ADM; RES; NRR; NMSS ADAMS Accession Numbers - Incoming: NONE Response/Package: NONE I.Ote norain Cross Reference Number: G20070600, LTR-07-0569 Staff Initiated: NO Related Task: Recurring Item: NO File Routing: EDATS Agency Lesson Learned: NO Roadmap Item: NO Action Type: Appropriate Action Priority: MediumL Sensitivity: None Signature Level: No Signature Required Urgency: NO OEDO Concurrence: NO OCM Concurrence: NO OCA Concurrence: NO Special Instructions: For Appropriate Action. Originator Name: Samuel W. Bodman Date of Incoming: 8/16/2007 Originating Organization: DOE Document Received by SECY Date: 8/29/2007 Addressee: Chairman Klein Date Response Requested by Originator: NONE Incoming Task Received: Letter Page 1 of l OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY CORRESPONDENCE CONTROL TICKET Date Printed: Aug 28, 2007 12:16 PAPER NUMBER: LTR-07-0569 LOGGING DATE: 08/27/2007 ACTION OFFICE: EDO AUTHOR: Samuel Bodman AFFILIATION: DOE ADDRESSEE: Dale Klein SUBJECT: Capabilities of the DOE and its contractors bring to bear on national security challenges ACTION: Appropriate DISTRIBUTION: LETTER DATE: 08/16/2007 ACKNOWLEDGED No SPECIAL HIANDLING: NOTES: FILE LOCATION: ADAMS DATE DUE: DATE SIGNED: EDO -- G20070600 The Secretary of Energy Washington, D.C. -

Alumni Columns, an Incomplete List of Past Student Government Presidents Was Printed

— -1— ce years and was dedicated this president Dr. Rene J. Bienvenu. Bienvenu served NSU for 32 biological sciences building at Northwestern was formally NSU The 1983. in memory of former president from 1978 through 1982. He died in spring as the Rene J. Bienvenu Hall for Biological Sciences NSU Biological Sciences Building Dedicated In Memory of Former University President and Louisiana Board of successful in industry and in academic conducted Feb. 8 the former research scientist, depart- Natchitoches, Ceremonies were and medical schools." chairman, dean and NSU Trustees for Colleges and Universities Northwestern State University to ment at J. Barkate noted, "Dr. Bienvenu was in were held executive director Dr. William Rene J. Bienvenu president who died 1983, formally dedicate the an outstanding teacher who left you with the 59th annual Junkin Jr. for Biological Sciences. in conjunction Hall the ceremonies for with the feeling that this fellow was meeting of the Louisiana Academy of Responding to The naming of the three-story person as a the family was the late NSU president's interested in you as a and biological sciences building, which Sciences. and he wanted to son, Shreveport pediatrician Dr. Steve microbiologist, was approved this Guest speakers were distinguished opened in 1970, was dean of the produce the very best students of Alumnus Dr. John Barkate, Bienvenu. His father winter by the Louisiana Board NSU he felt it would College of Science and Technology possible, because State Colleges and associate director of the U.S. Trustees for building reflect on his character." Department of Agriculture's Southern when the biological sciences Universities. -

3–27–00 Vol. 65 No. 59 Monday Mar. 27, 2000 Pages 16117–16296

3±27±00 Monday Vol. 65 No. 59 Mar. 27, 2000 Pages 16117±16296 VerDate 20-MAR-2000 17:38 Mar 24, 2000 Jkt 190000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\27MRWS.LOC pfrm11 PsN: 27MRWS 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 59 / Monday, March 27, 2000 The FEDERAL REGISTER is published daily, Monday through SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, PUBLIC Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Subscriptions: Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of Paper or fiche 202±512±1800 the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Assistance with public subscriptions 512±1806 Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. General online information 202±512±1530; 1±888±293±6498 Single copies/back copies: The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 512±1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 512±1803 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 523±5243 Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 523±5243 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

First Quarter Hanford Seismic Report for Fiscal Year 2011

PNNL-20302 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy Under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 First Quarter Hanford Seismic Report for Fiscal Year 2011 AC Rohay RE Clayton MD Sweeney JL Devary March 2011 PNNL-20302 First Quarter Hanford Seismic Report for Fiscal Year 2011 AC Rohay RE Clayton MD Sweeney JL Devary March 2011 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Richland, Washington 99352 Summary The Hanford Seismic Assessment Program (HSAP) provides an uninterrupted collection of high- quality raw and processed seismic data from the Hanford Seismic Network for the U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors. The HSAP is responsible for locating and identifying sources of seismic activity and monitoring changes in the historical pattern of seismic activity at the Hanford Site. The data are compiled, archived, and published for use by the Hanford Site for waste management, natural phenomena hazards assessments, and engineering design and construction. In addition, the HSAP works with the Hanford Site Emergency Services Organization to provide assistance in the event of a significant earthquake on the Hanford Site. The Hanford Seismic Network and the Eastern Washington Regional Network consist of 44 individual sensor sites and 15 radio relay sites maintained by the Hanford Seismic Assessment Team. The Hanford Seismic Network recorded 16 local earthquakes during the first quarter of FY 2011. Six earthquakes were located at shallow depths (less than 4 km), seven earthquakes at intermediate depths (between 4 and 9 km), most likely in the pre-basalt sediments, and three earthquakes were located at depths greater than 9 km, within the basement. -

Inmate Dies After Found Unconscious Family Member Claims Sumter Man Was Found with Needle in Arm, SLED Investigating

SPORTS Baron Classic Wilson Hall hosts rival Thomas Sumter, other regional teams in hoops tournament B1 SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2018 $1.75 LOCAL: Morris College named Purple Heart College A2 Inmate dies after found unconscious Family member claims Sumter man was found with needle in arm, SLED investigating BY ADRIENNE SARVIS sponsive with a needle in his arm" at She said nurses in the emergency The family member said Browder [email protected] about 3 a.m. Thursday. room who looked after Browder said had gastrointestinal bleeding, which She made these statements Friday Narcan had been administered, but he could indicate that he ingested, or ate, A Sumter-Lee Regional Detention morning. did not respond to it. something harmful, she said. Center inmate was pronounced dead She said she was told of Browder’s That indcates that it was not opioids A second family member said Saturday morning after he was found condition at 6:22 a.m. after he had nor heroin in his system, she said. Browder told his father he’d stopped unconscious Thursday morning, ac- gone into cardiac arrest three times. Browder only tested positive for eating cafeteria food at the jail after cording to Sumter County Sheriff's Of- “I should have been notified as soon marijuana, she said, and no one has hearing a rumor that someone fice. as he was found unresponsive,” she said what was in the syringe. planned to poison him. According to an immediate family said. No one knows how the needle got He only ate food from the vending member, Daniel Browder Jr., 38, was The family member said before into the prison, the family member machine, he said.