Channel Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I Casualty Biographies

St Martins-Milford World War I Casualty Biographies This memorial plaque to WW1 is in St Martin’s Church, Milford. There over a 100 listed names due to the fact that St Martin’s church had one of the largest congregations at that time. The names have been listed as they are on the memorial but some of the dates on the memorial are not correct. Sapper Edward John Ezard B Coy, Signal Corps, Royal Engineers- Son of Mr. and Mrs. J Ezard of Manchester- Husband of Priscilla Ezard, 32, Newton Cottages, The Friary, Salisbury- Father of 1 and 5 year old- Born in Lancashire in 1883- Died in hospital 24th August 1914 after being crushed by a lorry. Buried in Bavay Communal Cemetery, France (12 graves) South Part. Private George Hawkins 1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry- Son of George and Caroline Hawkins, 21 Trinity Street, Salisbury- Born in 1887 in Shrewton- He was part of the famous Mon’s retreat- His body was never found- Died on 21st October 1914. (818 died on that day). Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 19. Private Reginald William Liversidge 1st Dorsetshire Regiment- Son of George and Ellen Liversidge of 55, Culver Street, Salisbury- Born in 1892 in Salisbury- He was killed during the La Bassee/Armentieres battles- His body was never found- Died on 22nd October 1914 Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 22. Corporal Thomas James Gascoigne Shoeing Smith, 70th Battery Royal Field Artillery- Husband of Edith Ellen Gascoigne, 54 Barnard Street, Salisbury- Born in Croydon in 1887-Died on wounds on 30th September 1914. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

Glsww1rev7.Pdf

THE GLOUCESTERSHIRE REGIMENT CENOTAPH AND MEMORIALS TO THE OTHER FALLEN IN WW1 & WW2 WHICH ARE SITUATED BEHIND THE CENOTAPH ON A SCREEN WALL SITUATED IN GLOUCESTER PARK, IN THE CITY OF GLOUCESTER To the memory of the Fallen of the 1/5th & 2/5th Battalions The Gloucestershire Regiment 1/5th Battalion ADAMS Edgar Archibald Pte 2481 died 25/1/1916 age 24. Son of Samuel and Elizabeth 4 Fleet St Derby. At rest in Hebuterne Military Cemetery France I.E.16 ADAMS Philip Pte 33158 died 30/9/1917 age 21 Son of Edwin & Agnes 64 Forman’s Road Sparkhill Birmingham At rest in Buffs Road Cemetery Belgium E.42 ALDER Francis Charles Pte 2900 ‘A’ Coy died 16/8/1916 age 22 Son of G F of Stroud, Glos . At rest in Cerisy-Gailly Military Cemetery Somme France III.D.4 ALESBURY Sidney T, Pte 4922 died 27/8/1916 age 28 Son of Tom & Miriam 22 Horsell Moor, Woking. Commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial Somme ALFORD Stanley Albert, Pte 40297 died 4/11/1918 age 19 nephew of Coris Sanders of Holemoor Brandis Corner Devon. At rest in Landrecies British Cemetery France A.52 ALLAWAY Albert E Pte 4018 ‘A’ Coy died 23/7/1916 age 20 Son of Albert W & Mary E 63 Great Western Road Gloucester Commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial Somme ALLEN Harry P, Pte 260091 died 19/8/1917 Commemorated at Tyne Cot Memorial Belgium AMERY Ernest John, Pte 3084 died 23/7/1916 age 20 Son of John Witfill & Lillie Amelia 31 All Saints Terrace Hewlett Rd Cheltenham Commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial AMES John, Pte 34319 died 4/10/1917 Commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial Belgium XIII.B.28 AMOS William,Pte 203687 died 30/9/1917 Son of H & H Wynns Green Much Cowarne Bromyard Worcs husband of Elizabeth Annie Green Livers Ocle Cottages Ocle Pychard Burley Gate Herefordshire. -

In Grateful Memory of the Men of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo And

In grateful memory of the Men of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo and of this district who lost their lives in the service of their country in the Great War and in World War Two, and of their comrades who returned, having done their duty manfully. It is not the critic that counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or whether the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena…. who strives…. who spends himself…. and who at worst, if he fails, at least he fails in daring, so that his place will never be with those timid souls who know nothing of either victory or defeat. At the going down of the sun, And in the morning We will remember them. A cross of sacrifice stands in all Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries on the Western Front. The War Memorial of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo. It is 2010. In far off Afghanistan young men and women of various nations are putting their lives at risk as they struggle to defeat a tenacious enemy. We receive daily reports of the violent death of some while still in their teens. Others, of whom we hear little, are horribly maimed for life. We here, in the relative safety of the countries we call The British Isles, are free to discuss from our armchair or pub stool the rights and wrongs of such a conflict. That right of free speech, whatever our opinion or conclusion, was won for us by others, others who are not unlike today’s almost daily casualties of a distant war. -

1914 Pte Arthur Bertram Workman Was Born in Minchinhampton In

1914 2Lt Christopher Hal Lawrence was born in Chelsea in 1893. He applied for his commission on the day war was declared, and was gazetted in the 6th Bn Kings Royal Rifle Corps. He went to France on 20 September and was killed in action during the Battle of Aisne on 13 October 1914 in France at the age of 20. He was shot by a sniper. He is remembered on The La Ferté-sous-Jouarre Memorial. The La Ferté-sous-Jouarre Memorial commemorates 3,740 officers and men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) who fell at the battles of Mons, Le Cateau, the Marne and the Aisne between the end of August and early October 1914 and have no known graves. The YPRES (MENIN GATE) MEMORIAL now bears the names of more than 54,000 officers and men whose graves are not known. The Menin Gate is one of four memorials to the missing in Belgian Flanders which cover the area known as the Ypres Salient. Broadly speaking, the Salient stretched from Langemarck in the north to the northern edge in Ploegsteert Wood in the south, but it varied in area and shape throughout the war. Pte Frederick Ellins was born in Minchinhampton in 1894. He was in the 1st Bn Gloucestershire Regt and killed in action on 7th November 1914 in Flanders at the First Battle of Ypres at the age of 20. He is remembered on the Menin Gate at Ypres. Pte Gilbert Browne was born in London in 1889. He was in the 1st Bn Gloucestershire Regt and died on 9th November 1914 in Flanders at the First Battle of Ypres at the age of 25. -

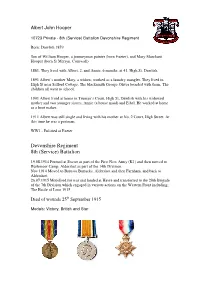

Devonshire Regiment 8Th (Service) Battalion

Albert John Hooper 10723 Private - 8th (Service) Battalion Devonshire Regiment Born: Dawlish 1879 Son of William Hooper, a journeyman painter (born Exeter), and Mary Marchant Hooper (born St Merryn, Cornwall) 1881, They lived with Albert, 2, and Annie, 6 months, at 41, High St, Dawlish. 1891 Albert’s mother Mary, a widow, worked as a laundry mangler. They lived in High St near Sidford Cottage. The blacksmith George Oliver boarded with them. The children all went to school. 1901 Albert lived at home in Truman’s Court, High St, Dawlish with his widowed mother and two younger sisters, Annie (a house maid) and Ethel. He worked at home as a boot maker. 1911 Albert was still single and living with his mother at No. 2 Court, High Street. At this time he was a postman. WW1 - Enlisted at Exeter Devonshire Regiment 8th (Service) Battalion 19.08.1914 Formed at Exeter as part of the First New Army (K1) and then moved to Rushmoor Camp, Aldershot as part of the 14th Division. Nov 1914 Moved to Barossa Barracks, Aldershot and then Farnham, and back to Aldershot. 26.07.1915 Mobilised for war and landed at Havre and transferred to the 20th Brigade of the 7th Division which engaged in various actions on the Western Front including; The Battle of Loos 1915 Died of wounds 25 th September 1915 Medals: Victory, British and Star Buried: Loos Memorial – panel 35 - 37 The Loos Memorial forms commemorates over 20,000 officers and men who have no known grave, who fell in the area from the River Lys to the old southern boundary of the First Army, east and west of Grenay. -

Visionner Les Qualités Propres À Chaque Site Ou Ensemble Mémoriel

N° D’IDEN SITE COMMUNE DEPARTEMENT (Fr) CRITERES TIFICAT PROVINCE (Be) DOMINANT ION WA01 Fort du Loncin Ans Liège Historique Architectural Identitaire Immatériel Original WA02 Carrés militaires de Liège Liège Robermont Historique Architectural Original WA03 Cimetière militaire français du Tintigny Luxembourg Plateau Historique WA04 Cimetière militaire français de Tintigny Luxembourg l’Orée de la Forêt Historique Architectural WA05 Cimetière militaire franco- Tintigny Luxembourg allemand du Radan Historique Architectural WA06 Enclos des fusillées à Tamines Sambreville Namur Historique Architectural Identitaire Original WA07 Cimetière militaire français de Fosses-la-Ville Namur la Belle Motte Historique WA08 Cimetière militaire allemand Mons Hainaut et du Commonwealth de Historique Saint-Symphorien Architectural Original WA09 Cimetière militaire du Comines-Warneton Hainaut Commonwealth "Hyde Park Historique Corner Cemetery" Immatériel Original WA10 Cimetière militaire et Comines-Warneton Hainaut monument aux disparus du Historique Commonwealth "Berks Immatériel Cemetery Extension" et Original "Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing" WA11 Cimetière militaire du Comines-Warneton Hainaut Commonwealth "Strand Historique Military Cemetery" Immatériel Original WA12 Cimetière militaire du Comines-Warneton Hainaut 2 Commonwealth "Prowse Point Historique Military Cemetery" Immatériel Original WA13 Cimetière militaire du Comines-Warneton Hainaut Historique Commonwealth "Mud Corner Immatériel Cemetery" Original WA14 Cimetière militaire du Comines-Warneton -

We Remember Those Members of the Lloyd's Community Who Lost Their

Surname First names Rank We remember those members of the Lloyd’s community who lost their lives in the First World War 1 We remember those who lost their lives in the First World War SurnameIntroduction Today, as we do each year, Lloyd’s is holding a But this book is the story of the Lloyd’s men who fought. Firstby John names Nelson, Remembrance Ceremony in the Underwriting Room, Many joined the County of London Regiment, either the ChairmanRank of Lloyd’s with many thousands of people attending. 5th Battalion (known as the London Rifle Brigade) or the 14th Battalion (known as the London Scottish). By June This book, brilliantly researched by John Hamblin is 1916, when compulsory military service was introduced, another act of remembrance. It is the story of the Lloyd’s 2485 men from Lloyd’s had undertaken military service. men who did not return from the First World War. Tragically, many did not return. This book honours those 214 men. Nine men from Lloyd’s fell in the first day of Like every organisation in Britain, Lloyd’s was deeply affected the battle of the Somme. The list of those who were by World War One. The market’s strong connections with killed contains members of the famous family firms that the Territorial Army led to hundreds of underwriters, dominated Lloyd’s at the outbreak of war – Willis, Poland, brokers, members and staff being mobilised within weeks Tyser, Walsham. of war being declared on 4 August 1914. Many of those who could not take part in actual combat also relinquished their This book is a labour of love by John Hamblin who is well business duties in order to serve the country in other ways. -

War Casualties, List of All Ver. 11 02.10.08

The Friends of Welford Road Cemetery, Leicester. A List of the Casualties of War who are either A. buried or B. commemorated in Welford Road Cemetery, Leicester All with rank, name, distinction, service number, date of death, age, place of burial Also other casualties in other conflicts buried or commemorated in WRC with [grave numbers] in square brackets. Voluntary £2 Donation Filename WRCWarCasAll11.DOC - page 1 – (originally created by C. E. John ASTON) updated 11/05/2018 18:26:00 The Friends of Welford Road Cemetery, Leicester. List of the Casualties of War who are A. buried or B. commemorated in Welford Road Cemetery with [grave number] in square brackets DANNEVOYE, Sergeant Joseph Jules, 54737, 09.11.14 [Uo1.202 WM between 10 & 11.4] A. Casualties buried in WRC,L DAVIES, Pte. T. H, S/6073, 03.11.1915 (37) [uO1.275 WM.17.3] DAVIS, Sergt. Joseph Samuel, 5397, 30.08.1919 (39) [uO1.388 WM.39.3] De GOTTE, Soldat Jules Joseph 23530, 31.10.1914 Casualties of the First World War [uO1.202 WM between 10 & 11.1] *Repatriated to Belgium 1923 04.08.1914 to 31.08.1921 DEACON, Pte. John William, 4204, 05.10.1915 (25) [uO.1066] De TOURNEY, Soldat Charles Albert 53121, 05.11.1914 ABBOTT, Pte. Alfred, 201748, 03.02.1917 (25) [cE1.406] [uO1.202 WM between 10 & 11.3] ALLARD, Pte. 3684, 12.10.1918 (21) [cD.240] DOYLE, Pte. John, 23593, 10.09.1918 [uO1.208 WM.5.1] ALLEN, Pte. Edward, 21438, 05.04.1919 (28) [uO1.367 WM.38.2] DUNK, Rfn. -

PRESS GALLERY MEMORIAL FIRST WORLD WAR Name

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Press Gallery, First World War PRESS GALLERY MEMORIAL FIRST WORLD WAR Name (as on memorial) Full name MP/Peer/Son of... Newspaper Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death Additional information Sources Son of W. H. Brayden, O.B.E., and Ethel 23/12/1917 London Regiment, Irish Rifles Buried at the Jerusalem War Cemetery, Mary Brayden (nee Shiell), of 28, Parliamentary Archives HC/SA/SJ/12/7; Brayden, K. Kevin Brayden Press Freeman's Journal (aged 26) 2nd Lieutenant 2nd/18th Battalion Israel Adelaide Rd., Dublin. CWGC Son of Mrs. H. Goldsworthy, of Ilfracombe; husband of Isabelle 19/06/1917 London Regiment, London Rifle Buried at Guemappe British Cemetery, Goldsworthy, of 23, Little Ealing Lane, Parliamentary Archives HC/SA/SJ/12/7; Goldsworthy, L.H. Linden Henry Goldsworthy Press Pall Mall Gazette (aged 38) Rifleman Brigade 5th Battalion Wancourt, France South Ealing, London. CWGC Buried at Hancourt British Cemetery, Parliamentary Archives HC/SA/SJ/12/7; McCallum, J. James McCallum Press Press Association 21/09/1918 Gunner Royal Field Artillery France CWGC Drowned during the sinking of Hired Transport 'Transilvania' off Cape Vado; commemorated on the Savona Parliamentary Archives HC/SA/SJ/12/7; Prior, E.J. Edward John Prior Press Central News 04/05/1917 Corporal Army Service Corps (Canteens) Memorial, Italy CWGC 01/07/1916 Wiltshire Regiment, General List and Buried at Carnoy Military Cemetery, Son of Mrs Martha A. Crompton, of 22, Parliamentary Archives HC/SA/SJ/12/7; Rushton, F.G. Frank Gregson Rushton Press Daily Dispatch (aged 30) 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Bn. -

MOTTINGHAM WAR MEMORIAL the Men of Mottingham Who Gave Their Lives in the Great War 1914-1918

MOTTINGHAM WAR MEMORIAL The Men of Mottingham who gave their lives in the Great War 1914-1918 The Grade II listed Mottingham War Memorial at the junctions of Grove Park Road, Mottingham Road and West Park was unveiled on 26th March 1920 to commemorate the 44 men of Mottingham, including three pairs of brothers, who gave their lives for God, King and Country in the First World War Surname & Initials (as shown on memorial) BLAKE C.S Given Names Charles Stanley Rank & Service Number Captain (T) Commissioned Regiment or Unit Prince of Wales's Volunteers (South Lancashire) Regt. 10th Battalion Date, Age And Circumstances of Death Killed in Action 7th August 1915, aged 35 Place of Death Gallipoli, Turkey Cemetery or Memorial Helles Memorial, Gallipoli, Turkey Significant Address (and source) Oakhurst, 9 Clarence Road, Mottingham (Source:1911 Census/Probate) Occupation Building Surveyor for London County Council Notes Brother of Francis Seymour Blake Previously 15th City of London Regt. Regt. No.397 Surname & Initials (as shown on memorial) BLAKE F.S Given Names Francis Seymour Rank & Service Number Captain (T) Commissioned Regiment or Unit The King's Liverpool Regt., 15th Battalion Attached to 2nd Battn South Wales Borderers Date, Age And Circumstances of Death Killed in Action 1st July 1916, aged 38 Place of Death Somme, France Cemetery or Memorial Thiepval Memorial, Somme, France Significant Address (and source) 11 Avondale Road, Mottingham (Source:Probate) Occupation Actuarial Assistant in L.C.C Notes Brother of Charles Stanley Blake Previously 15th City of London Regt. Regt. No 398 Surname & Initials (as shown on memorial) BRIGNALL F. -

Men of Ashdown Forest Who Fell in the First World War and Are

Men of Ashdown Forest who Fell in the First World War and are Commemorated at Forest Row, Hartfield and Coleman’s Hatch A Collection of Case Studies 1 Published by Ashdown Forest Research Group The Ashdown Forest Centre Wych Cross Forest Row East Sussex RH18 5JP website: http://www.ashdownforest.org/enjoy/history/AshdownResearchGroup.php email: [email protected] First published August 2014 This revised edition published October 2015. © Ashdown Forest Research Group 2 CONTENTS Click on the person’s name to jump to his case study 05 INTRODUCTION 06 Bassett, James Baldwin 08 Biddlecombe, Henry George 11 Brooker, Charles Frederick 13 Edwards, Frederick Robert 17 Fisher, George Kenneth Thompson 19 Fry, Frederick Samuel 21 Heasman, George Henry 23 Heasman, Frederick James 25 Kekewich, John 28 Lawrence, Michael Charles 31 Lawrence, Oliver John 34 Luxford, Edward James 36 Maskell, George 38 Medhurst, John Arthur 40 Mellor, Benjamin Charles 42 Mitchell, Albert 44 Page, Harry 45 Polehampton, Frederick William 50 Robinson, Cyril Charles 51 Robson, Robert Charles 3 53 Sands, Alfred Jesse 55 Sands, William Thomas 57 Shelley, Ewbert John 59 Simmons, James 61 Sippetts, Jack Frederick 63 Sykes, William Ernest 65 Tomsett, Albert Ernest Standen 67 Upton, Albert James 69 Vaughan, Ernest Stanley 70 Waters, Eric Gordon 72 Weeding, George 74 Weeding, John 75 Wheatley, Harry 76 Wheatley, Doctor 78 Wheatley, William James 80 SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 Introduction This collection of case studies of Ashdown Forest men who fell during the Great War was first published by Ashdown Forest Research Group to mark the 100th anniversary of the declaration of war by Great Britain on Germany on 4 August 1914, a war which was to have a devastating impact on the communities of Ashdown Forest as it was on the rest of the country.