Anselm Berrigan First Published by Background Publishing in 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

230-Newsletter.Pdf

$5? The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Macgregor Card Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Josef Kaplan Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Brett Price Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Stephen Rosenthal Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Courtney Frederick, Vanessa Garver, Jeffrey Grunthaner Interns/Volunteers: Nina Freeman, Julia Santoli, Alex Duringer, Jim Behrle, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Erica Wessmann, Susan Landers, Douglas Rothschild, Alex Abelson, Aria Boutet, Tony Lancosta, Jessie Wheeler, Ariel Bornstein Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), Rosemary Carroll (Treasurer), Kimberly Lyons (Secretary), Todd Colby, Mónica de la Torre, Ted Greenwald, Tim Griffin, John S. Hall, Erica Hunt, Jonathan Morrill, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly, Christopher Stackhouse, Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; and are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

227-Newsletter.Pdf

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.org APR/MAY 2011 #227 LETTERS POEM NATHANIEL MACKEY INTERVIEW CARLA HARRYMAN & LYN HEJINIAN TALK WITH CORINA COPP CALENDAR PATRICK JAMES DUNAGAN REVIEWS CHAPBOOKS BY ARIEL GOLDBERG, JESSICA FIORINI, JIM CARROLL, ALLI WARREN & NICHOLAS JAMES WHITTINGTON CATHERINE WAGNER REVIEWS ANDREA BRADY CACONRAD REVIEWS SUSIE TIMMONS FARRAH FIELD REVIEWS PAUL LEGAULT CARLEY MOORE REVIEWS EILEEN MYLES ERIK ANDERSON REVIEWS RENEE GLADMAN DAVID BRAZIL REVIEWS MINA PAM DICK STEPHANIE DICKINSON REVIEWS LEWIS WARSH MATT LONGABUCCO REVIEWS MIŁOSZ BIEDRZYCKI JAMIE TOWNSEND REVIEWS PAUL FOSTER JOHNSON ABRAHAM AVNISAN REVIEWS CAROLINE BERGVALL NICOLE TRIGG REVIEWS JULIANA LESLIE ERICA KAUFMAN REVIEWS KARINNE KEITHLEY $5? 02 APR/MAY 11 #227 THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Corina Copp DISTRIBUTION: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR: Arlo Quint PROGRAM ASSISTANT: Nicole Wallace MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Macgregor Card MONDAY NIGHT TALK SERIES COORDINATOR: Michael Scharf WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Joanna Fuhrman FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATORS: Brett Price SOUND TECHNICIAN: David Vogen VIDEOGRAPHER: Alex Abelson BOOKKEEPER: Stephen Rosenthal ARCHIVIST: Will Edmiston BOX OFFICE: Courtney Frederick, Kelly Ginger, Vanessa Garver INTERNS: Nina Freeman, Stephanie Jo Elstro, Rebecca Melnyk VOLUNTEERS: Jim Behrle, Rachel Chatham, Corinne Dekkers, Ivy Johnson, Erica Kaufman, Christine Kelly, Ace McNamara, Annie Paradis, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Lauren Russell, Thomas Seely, Erica Wessmann, Alice Whitwham, Dustin Williamson The Poetry Project Newsletter is published four times a year and mailed free of charge to members of and contributors to the Poetry Project. Subscriptions are available for $25/year domestic, $45/year international. -

New Director, New Era Begin at Poetry Project by GREG FUCHS He Poetry Project at St

Issue 10 October 2003 BOOG CITY Free New Director, New Era Begin at Poetry Project BY GREG FUCHS he Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery (131 East 10th St.), legendary for nurturing many radical TAmerican voices, including Kathy Acker, Richard Hell, Ed Sanders, and Patti Smith, has a new artistic director. Quietly this summer, Anselm Berrigan accepted the duties from Ed Friedman, who announced in February that he would step down to spend I’ve got a job to do—keep the place going, extend its good parts, adapt to the 21st century, and figure out exactly what The Poetry Project community is right now. more time with his family and to provide the next generation its opportunity to direct the Project. Following a search that lasted throughout the winter, Berrigan was offered the job by the Project’s board of directors in April. This appointment is logical and refreshing. Like all of the Project’s directors, Berrigan is a charming, iconoclastic, and Anselm Berrigan, St. Mark’s Church courtyard. sophisticated poet. After studying with Allen Ginsberg at Greg Fuchs photo Brooklyn College in the 1990s, Berrigan worked as the program assistant and coordinator of the Monday night reading series at the Project. His readings in New York City have become recently spawned movements like the When was the fire that burned the East Side. One at the 10th Street Café, increasingly popular and he’s published three terrific volumes of independent media renaissance to keep Project? and the other at Les Deux Magots, which poetry with Edge Books of Washington, D.C. -

The Poetry Project at 50

The Poetry Project december 2016 / january 2017 Issue #249 The Poetry Project december 2016 / January 2017 Issue #249 Director: Stacy Szymaszek Managing Director: Nicole Wallace Archivist: Will Edmiston Program Director: Simone White Archival Assistant: Marlan Sigelman Communications & Membership Coordinator: Laura Henriksen Bookkeeper: Carlos Estrada Newsletter Editor: Betsy Fagin Workshop/Master Class Leaders (Spring 2017): Lisa Jarnot, Reviews Editor: Sara Jane Stoner Pierre Joris, and Matvei Yankelevich Monday Night Readings Coordinator: Judah Rubin Box Office Staff: Micaela Foley, Cori Hutchinson, and Anna Wednesday Night Readings Coordinator: Simone White Kreienberg Friday Night Readings Coordinator: Ariel Goldberg Interns: Shelby Cook, Iris Dumaual, and Cori Hutchinson Friday Night Readings Assistant: Yanyi Luo Newsletter Consultant: Krystal Languell Volunteers Mehroon Alladin, Mel Elberg, Micaela Foley, Hadley Gitto, Jessica Gonzalez, Olivia Grayson, Cori Hutchinson, Raffi Kiureghian, Anna Kreienberg, Phoebe Lifton, Ashleigh Martin, Dave Morse, Batya Rosenblum, Isabelle Shallcross, Hannah Treasure, Viktorsha Uliyanova, and Shanxing Wang. Board of Directors Camille Rankine (Chair), Katy Lederer (Vice-Chair), Carol Overby (Treasurer), and Kristine Hsu (Secretary), Todd Colby, Adam Fitzgerald, Boo Froebel, Erica Hunt, Jonathan Morrill, Elinor Nauen, Laura Nicoll, Purvi Shah, Jo Ann Wasserman, and David Wilk. Friends Committee Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Will Creeley, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Viki Hudspith, -

235-Newsletter.Pdf

The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Simone White Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Corrine Fitzpatrick Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Matt Longabucco Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Lezlie Hall Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Aria Boutet, Courtney Frederick, Gabriella Mattis Interns/Volunteers: Mel Elberg, Phoebe Lifton, Jasmine An, Davy Knittle, Olivia Grayson, Catherine Vail, Kate Nichols, Jim Behrle, Douglas Rothschild Volunteer Development Committee Members: Stephanie Gray, Susan Landers Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), John S. Hall (Vice-President), Jonathan Morrill (Treasurer), Jo Ann Wasserman (Secretary), Carol Overby, Camille Rankine, Kimberly Lyons, Todd Colby, Ted Greenwald, Erica Hunt, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly and Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Will Creeley, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs and publications are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Poetry Project’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

University of Birmingham Space Occupied

University of Birmingham Space occupied Cran, Rona DOI: 10.1017/S0021875820001073 License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Cran, R 2020, 'Space occupied: women poet-editors and the mimeograph revolution in mid-century New York City', Journal of American Studies. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875820001073 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: This article has been published in a revised form in Journal of American Studies [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875820001073]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution or re-use. © Cambridge University Press 2020. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

Court Green Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2015 Court Green: Dossier: On the Occasion Of Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: On the Occasion Of" (2015). Court Green. 12. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Read good poetry!” —William Carlos Williams COURT GREEN 12 COURT 12 EDITORS CM Burroughs and Tony Trigilio MANAGING EDITOR Cora Jacobs SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Jacob Victorine EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Cameron Decker, Patti Pangborn, Taylor Pedersen, and Andre Price Court Green is published annually in association with Columbia College Chicago, Department of Creative Writing. Our thanks to Matthew Shenoda, Interim Chair, Department of Creative Writing; Suzanne Blum-Malley, Interim Dean, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Stanley T. Wearden, Provost; and Kwang-Wu Kim, President and CEO of Columbia College Chicago. Court Green was founded in 2004 by Arielle Greenberg, Tony Trigilio, and David Trinidad. Acknowledgments for this issue can be found on page 209. Court Green is distributed by Ingram Periodicals and Media Solutions. Copyright © 2015 by Columbia College Chicago. ISSN 1548-5242. Magazine cover design by Hannah Rebernick, Columbia College Chicago Creative Services. -

BERRIGAN, TED. Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley Collection, 1954-1983

BERRIGAN, TED. Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley collection, 1954-1983 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Berrigan, Ted. Title: Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley collection, 1954-1983 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1135 Extent: 2.5 linear feet (5 boxes), 1 oversized papers boxes, and 1 bound volume (BV) Abstract: Artificially created collection relating to New York poet Ted Berrigan, including writings, photographs, and printed material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Ted Berrigan papers, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut; Ted Berrigan papers, Syracuse University; and Ted Berrigan papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library. Source Purchased from James S. Jaffe Rare Books, 2010. Additions were purchased from 2011 to 2015. Custodial History Purchased from dealer, provenance unknown. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley collection, 1970-1980 Manuscript Collection No. 1135 Appraisal Note Acquired by Curator of Literary Collections and the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library, Kevin Young, as part of the Rose Library's holdings in American literature. -

The Poetry Project Newsletter #206, February/March 2006

#206 FEBRUARY/MARCH 2006 IDLE REMOTE SHREWD DANGEROUS DRINKER LONER FARMBORN HOTHEAD ACADEMIC BITTER AMBITIOUS OBSCURE GAMBLER CELEBRATED LIAR OBSESSIVE HARMLESS INSCRUTABLE AMUSING CLIMBER PRICE $5.00 ST. MARK’S CHURCH IN-THE-BOWERY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 www.poetryproject.com #206 FEBRUARY / MARCH 2006 NEWSLETTER EDITOR Brendan Lorber 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 FROM THE DIRECTOR NEW YEAR’S THANK YOUS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. STAFF FROM THE EDITOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Anselm Berrigan AN APPRECIATION OF OUR TOKEN PROGRAM COORDINATOR Stacey Szymaszek PROGRAM ASSISTANT Corrine Fitzpatrick FAREWELL TORY DENT MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Corina Copp MONDAY NIGHT TALK SERIES COORDINATOR Renee Gladman FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Regie Cabico 7 WORLD NEWS SOUND TECHNICIANS Corrine Fitzpatrick, Arlo Quint, David Vogen BREAKING REPORTS JUST IN FROM BOOKKEEPER Stephen Rosenthal ALBANY / AUSTIN / BOSTON / BROOKLYN DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANT Stephanie Gray BUFFALO / THE CATSKILLS / ITALY / ITHACA BOX OFFICE Charles Babinski, Courtney Frederick, Erica Kaufman, Michael Nicoloff, Joanna Sondheim PETALUMA / PHILADELPHIA / SAN DIEGO / INTERNS Kathryn Coto, Stacy Garrett, Laura Humpal, Evan Kennedy, Stefania Marthakis, Erika Recordon VOLUNTEERS David Cameron, Miles Champion, Jess Fiorini, Colomba Johnson, Eugene Lim, Sirius SEATTLE / SLOVAKIA / SPAIN / THE TWIN CITIES McLorbotague, Perdita Morty Rufus, Jessica Rogers, Lauren Russell, Bethany Spiers, Joy Surles-Tirpak, Pig Weiser-Berrigan 16 EVENTS THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER is published four times a year and mailed free of charge FEBRUARY & MARCH to members of and contributors to the Poetry Project. Subscriptions are available for $25/year domestic, $35/year international. Checks should be made payable to The Poetry Project, St. -

Anselm Berrigan and John Godfrey Readings in Contemporary Poetry Thursday, September 22, 2011, 6:30 Pm

Dia Art Foundation Anselm Berrigan and John Godfrey Readings in Contemporary Poetry Thursday, September 22, 2011, 6:30 pm Introduction by Vincent Katz Anselm Berrigan Anselm Berrigan was born on August 14, 1972 in Chicago, where his parents, Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley, where living. Anselm is the author of several books of poetry, including Free Cell (City Lights Spotlight, 2009) and the just-published book-length poem Notes from Irrelevance (Wave, 2011). From 2003 to 2007, he was Artistic Director of The Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church. He currently teaches at Pratt Institute and Wesleyan University and co-chairs Writing at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts. He is the poetry editor for The Brooklyn Rail. Reading Anselm Berrigan’s poetry gives one the feeling of being swept along by a current, in whose waves and ripples the reader is comfortably conveyed. Comfortable, because your guide has taken care to make your trip a lively one, entertaining, verbally playful, emotionally intense, seemingly revealing of the poet who wrote these poems — but how much, after all, do we know about Anselm? The I in these poems is well-versed in the New York School gambit of the fluctuating narrator. You could say it’s in his DNA. In a poem entitled “Not all there,” dedicated to Alice Notley, from his first book, the poet wanders around the subject, the way O’Hara wandered around midtown, before revealing that he saw a New York Post with her face on it. Anselm in this poem wanders from Buffalo to New York to San Francisco to Paris. -

Front Matter

The Stamp of Class The Stamp of Class Re›ections on Poetry & Social Class Gary Lenhart THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2006 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2009 2008 2007 2006 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lenhart, Gary. The stamp of class : reflections on poetry and social class / Gary Lenhart. p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-0-472-09917-7 (acid-free paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-09917-5 (acid-free paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-06917-0 (pbk. : acid-free paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-06917-9 (pbk. : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Working class in literature. 3. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892—Political and social views. 4. Yearsley, Ann, 1753–1806—Criticism and interpretation. 5. Duck, Stephen, 1705–1756—Criticism and interpretation. 6. Literature and society—English-speaking countries. 7. Working class writings—History and criticism. 8. Social classes in literature. I. Title. PS310.W67.L46 2006 2005016613 To my parents, who provided me with board and plenty of room, tempered my excesses with their love, and continue to serve as models of generosity; and my forbearing daughter and wife, who are my abiding loves and inspiration. -

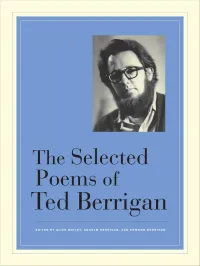

Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan

The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Jamie and David Wolf and the Rosenthal Family Foundation as members of the Publisher’s Circle of the University of California Press Foundation. The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan Edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished univer- sity presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2011 by The Regents of the University of California Poems from The Sonnetsby Ted Berrigan, copyright © 2000 by Alice Notley, Literary Executrix of the Estate of Ted Berrigan. Used by per- mission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Berrigan, Ted. [Poems. Selections] The selected poems of Ted Berrigan / edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn: 978-0-520-26683-4 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn: 978-0-520-26684-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Notley, Alice 1945– II. Berrigan, Anselm. III. Berrigan, Edmund, 1974– IV. Title.