Deleuze, Guattari and the Production of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

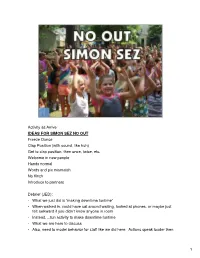

Activity As Arrive IDEAS for SIMON SEZ NO out Freeze Dance Clap Position (With Sound, Like Huh) Get to Clap Position, Then Once, Twice, Etc

Activity as Arrive IDEAS FOR SIMON SEZ NO OUT Freeze Dance Clap Position (with sound, like huh) Get to clap position, then once, twice, etc. Welcome in new people Hands normal Words and pix mismatch No flinch Introduce to partners Debrief (JED): - What we just did is “making downtime funtime” - When walked in, could have sat around waiting, looked at phones, or maybe just felt awkward if you didn’t know anyone in room - Instead….fun activity to make downtime funtime - What we are here to discuss - Also, need to model behavior for staff like we did here. Actions speak louder then 1 words….need to walk the talk! - Bonus Debrief! (ROZ) - Why great camp game? - For those that focus on building life skills or 21 st century skills, does it in a fun way…. - Listening Skills - Cooperation/ collaboration (instead of competition) - OK to laugh at yourself - Practice makes you better at everything! - Everyone can have a seat…. 1 ROZ 3:30 – 5 MRPA Thanks for joining us. Announcements from Conference…. Love this session because lots of play. ALSO….a fun benefit of technology…you are going to help determine the content in a few minutes. Going to talk about how you make every minute of the camp day a unique & special part of the experience. We will explore the different times in the camp day when staff can easily transition down-time into fun-time using creative games, activities, songs, dances and more. Can email presentation. Don’t waste paper…give cards at end to email or sign 3 sheet. -

Hume's Objects After Deleuze

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School March 2021 Hume's Objects After Deleuze Michael P. Harter Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Harter, Michael P., "Hume's Objects After Deleuze" (2021). LSU Master's Theses. 5305. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/5305 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUME’S OBJECTS AFTER DELEUZE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies by Michael Patrick Harter B.A., California State University, Fresno, 2018 May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Human beings are wholly dependent creatures. In our becoming, we are affected by an incredible number of beings who aid and foster our growth. It would be impossible to devise a list of all such individuals. However, those who played imperative roles in the creation of this work deserve their due recognition. First, I would like to thank my partner, Leena, and our pets Merleau and the late Kiki. Throughout the ebbs and flows of my academic career, you have remained sources of love, joy, encouragement, and calm. -

Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum

Language Arts Grades K-2: Reading Foundations Skills Block Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum K-2 Reading Foundations Skills Block: Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum is published by: EL Education 247 W. 35th Street, 8th Floor New York, NY 10001 www.ELeducation.org ISBN 978-1683622710 FIRST EDITION © 2016 EL Education Inc. Except where otherwise noted, EL Education’s Language Arts Curriculum is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/. Licensed third party content noted as such in this curriculum is the property of the respective copyright owner and not subject to the CC BY 4.0 License. Responsibility for securing any necessary permissions as to such third party content rests with parties desiring to use such content. For example, certain third party content may not be reproduced or distributed (outside the scope of fair use) without additional permissions from the content owner and it is the responsibility of the person seeking to reproduce or distribute this curriculum to either secure those permissions or remove the applicable content before reproduction or distribution. Common Core State Standards © Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights reserved. Common Core State Standards are subject to the public license located at http://www.corestandards.org/public-license/. Cover art from “First Come the Eggs,” a project by third grade students at Genesee Community Charter School. Used courtesy of Genesee Community Charter School, Rochester, NY. -

Scouting Games. 61 Horse and Rider 54 1

The MacScouter's Big Book of Games Volume 2: Games for Older Scouts Compiled by Gary Hendra and Gary Yerkes www.macscouter.com/Games Table of Contents Title Page Title Page Introduction 1 Radio Isotope 11 Introduction to Camp Games for Older Rat Trap Race 12 Scouts 1 Reactor Transporter 12 Tripod Lashing 12 Camp Games for Older Scouts 2 Map Symbol Relay 12 Flying Saucer Kim's 2 Height Measuring 12 Pack Relay 2 Nature Kim's Game 12 Sloppy Camp 2 Bombing The Camp 13 Tent Pitching 2 Invisible Kim's 13 Tent Strik'n Contest 2 Kim's Game 13 Remote Clove Hitch 3 Candle Relay 13 Compass Course 3 Lifeline Relay 13 Compass Facing 3 Spoon Race 14 Map Orienteering 3 Wet T-Shirt Relay 14 Flapjack Flipping 3 Capture The Flag 14 Bow Saw Relay 3 Crossing The Gap 14 Match Lighting 4 Scavenger Hunt Games 15 String Burning Race 4 Scouting Scavenger Hunt 15 Water Boiling Race 4 Demonstrations 15 Bandage Relay 4 Space Age Technology 16 Firemans Drag Relay 4 Machines 16 Stretcher Race 4 Camera 16 Two-Man Carry Race 5 One is One 16 British Bulldog 5 Sensational 16 Catch Ten 5 One Square 16 Caterpillar Race 5 Tape Recorder 17 Crows And Cranes 5 Elephant Roll 6 Water Games 18 Granny's Footsteps 6 A Little Inconvenience 18 Guard The Fort 6 Slash hike 18 Hit The Can 6 Monster Relay 18 Island Hopping 6 Save the Insulin 19 Jack's Alive 7 Marathon Obstacle Race 19 Jump The Shot 7 Punctured Drum 19 Lassoing The Steer 7 Floating Fire Bombardment 19 Luck Relay 7 Mystery Meal 19 Pocket Rope 7 Operation Neptune 19 Ring On A String 8 Pyjama Relay 20 Shoot The Gap 8 Candle -

Throbbing Gristle 40Th Anniv Rough Trade East

! THROBBING GRISTLE ROUGH TRADE EAST EVENT – 1 NOV CHRIS CARTER MODULAR PERFORMANCE, PLUS Q&A AND SIGNING 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEBUT ALBUM THE SECOND ANNUAL REPORT Throbbing Gristle have announced a Rough Trade East event on Wednesday 1 November which will see Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti in conversation, and Chris Carter performing an improvised modular set. The set will be performed predominately on prototypes of a brand new collaboration with Tiptop Audio. Chris Carter has been working with Tiptop Audio on the forthcoming Tiptop Audio TG-ONE Eurorack module, which includes two exclusive cards of Throbbing Gristle samples. Chris Carter has curated the sounds from his personal sonic archive that spans some 40 years. Card one consists of 128 percussive sounds and audio snippets with a second card of 128 longer samples, pads and loops. The sounds have been reworked and revised, modified and mangled by Carter to give the user a unique Throbbing Gristle sounding palette to work wonders with. In addition to the TG themed front panel graphics, the module features customised code developed in collaboration with Chris Carter. In addition, there will be a Throbbing Gristle 40th Anniversary Q&A event at the Rough Trade Shop in New York with Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, date to be announced. The Rough Trade Event coincides with the first in a series of reissues on Mute, set to start on the 40th anniversary of their debut album release, The Second Annual Report. On 3 November 2017 The Second Annual Report, presented as a limited edition white vinyl release in the original packaging and also on double CD, and 20 Jazz Funk Greats, on green vinyl and double CD, will be released, along with, The Taste Of TG: A Beginner’s Guide to Throbbing Gristle with an updated track listing that will include ‘Almost A Kiss’ (from 2007’s Part Two: Endless Not). -

Deleuze and the Simulacrum Between the Phantasm and Fantasy (A Genealogical Reading)

Tijdschrift voor Filosofie, 81/2019, p. 131-149 DELEUZE AND THE SIMULACRUM BETWEEN THE PHANTASM AND FANTASY (A GENEALOGICAL READING) by Daniel Villegas Vélez (Leuven) What is the difference between the phantasm and the simulacrum in Deleuze’s famous reversal of Platonism? At the end of “Plato and the Simulacrum,” Deleuze argues that philosophy must extract from moder- nity “something that Nietzsche designated as the untimely.”1 The his- toricity of the untimely, Deleuze specifies, obtains differently with respect to the past, present, and future: the untimely is attained with respect to the past by the reversal of Platonism and with respect to the present, “by the simulacrum conceived as the edge of critical moder- nity.” In relation to the future, however, it is attained “by the phantasm of the eternal return as belief in the future.” At stake, is a certain dis- tinction between the simulacrum, whose power, as Deleuze tells us in this crucial paragraph, defines modernity, and the phantasm, which is Daniel Villegas Vélez (1984) holds a PhD from the Univ. of Pennsylvania and is postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Philosophy, KU Leuven, where he forms part of the erc Research Pro- ject Homo Mimeticus (hom). Recent publications include “The Matter of Timbre: Listening, Genea- logy, Sound,” in The Oxford Handbook of Timbre, ed. Emily Dolan and Alexander Rehding (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2018), doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190637224.013.20 and “Allegory, Noise, and History: TheArcades Project Looks Back at the Trauerspielbuch,” New Writing Special Issue: Convo- luting the Dialectical Image (2019), doi: 10.1080/14790726.2019.1567795. -

Overturning the Paradigm of Identity with Gilles Deleuze's Differential

A Thesis entitled Difference Over Identity: Overturning the Paradigm of Identity With Gilles Deleuze’s Differential Ontology by Matthew G. Eckel Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy Dr. Ammon Allred, Committee Chair Dr. Benjamin Grazzini, Committee Member Dr. Benjamin Pryor, Committee Member Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2014 An Abstract of Difference Over Identity: Overturning the Paradigm of Identity With Gilles Deleuze’s Differential Ontology by Matthew G. Eckel Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy The University of Toledo May 2014 Taking Gilles Deleuze to be a philosopher who is most concerned with articulating a ‘philosophy of difference’, Deleuze’s thought represents a fundamental shift in the history of philosophy, a shift which asserts ontological difference as independent of any prior ontological identity, even going as far as suggesting that identity is only possible when grounded by difference. Deleuze reconstructs a ‘minor’ history of philosophy, mobilizing thinkers from Spinoza and Nietzsche to Duns Scotus and Bergson, in his attempt to assert that philosophy has always been, underneath its canonical manifestations, a project concerned with ontology, and that ontological difference deserves the kind of philosophical attention, and privilege, which ontological identity has been given since Aristotle. -

Primal Scream Juntam-Se Ao Cartaz Do Nos Alive'19

COMUNICADO DE IMPRENSA 02 / 04 / 2019 NOS apresenta dia 12 de julho PRIMAL SCREAM JUNTAM-SE AO CARTAZ DO NOS ALIVE'19 Os escoceses Primal Scream são a mais recente confirmação do NOS Alive’19. A banda liderada por Bobby Gillespie, figura incontornável da música alternativa, sobe ao Palco NOS dia 12 de julho juntando-se assim aos já anunciados Vampire Weekend, Gossip e Izal no segundo dia do festival. Com mais de 30 anos de carreira, Primal Scream trazem até ao Passeio Marítimo de Algés o novo álbum com data de lançamento previsto a 24 de maio, “Maximum Rock N Roll: The Singles”, trabalho que reúne os singles da banda desde 1986 até 2016 em dois volumes. A compilação começa com “Velocity Girl”, passando por temas dos dois primeiros álbuns como são exemplo "Ivy Ivy Ivy" e "Loaded". A banda que tinha apresentado em outubro de 2018 a mais recente compilação de singles originais do quarto álbum de 1994 com “Give Out But Don’t Give Up: The Original Memphis Recordings”, juntando-se ao lendário produtor Tom Dowd, a David Hood (baixo) e Roger Hawkins (bateria) no Ardent Studios em Memphis, está de volta às gravações e revelam algo nunca antes ouvido e uma banda que continua a surpreender. Primal Scream foi uma parte fundamental da cena indie pop dos anos 80, depois do galardoado disco "Screamadelica" vencedor do Mercury Prize em 1991, considerado um dos maiores de todos os tempos, a banda seguiu por influências de garage rock e dance music até ao último trabalho discográfico “Chaosmosis” lançado em 2016. -

Gilles Deleuze's

Gilles Deleuze’s Empiricism and Subjectivity 55194_Roffe194_Roffe andand Deleuze.inddDeleuze.indd i 115/10/165/10/16 4:574:57 PPMM Leopards break into the temple and drink all the sacrifi cial vessels dry; it keeps happening; in the end, it can be calculated in advance and is incorporated into the ritual. Franz Kafka 55194_Roffe194_Roffe andand Deleuze.inddDeleuze.indd iiii 115/10/165/10/16 4:574:57 PPMM Gilles Deleuze’s Empiricism and Subjectivity A Critical Introduction and Guide JON ROFFE 55194_Roffe194_Roffe andand Deleuze.inddDeleuze.indd iiiiii 115/10/165/10/16 4:574:57 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: www.edinburghuniversitypress.com © Jon Roffe, 2016 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11.5/15 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 0582 9 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0584 3 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0583 6 (paperback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0585 0 (epub) The right of Jon Roffe to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. -

Wiseman-Trowse20134950

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Book Section Title: The singer and the song: Nick Cave and the archetypal function of the cover version Creators: Wiseman-Trowse, N. J. B. R Example citation: Wiseman-Trowse, N. J. B. (2013) The singer and the song: Nick Cave and the archetypal function oAf the cover version. In: Baker, J. (ed.) The Art of Nick Cave: New Critical Essays. Bristol: Intellect. pp. 57-84. T Version: Final draft C NhttEp://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/4950/ The singer and the song: Nick Cave and the archetypal function of the cover version Nathan Wiseman-Trowse The University of Northampton A small proscenium arch of red light bulbs framing draped crimson curtains fills the screen. It is hard to tell whether the ramshackle stage is inside or outside but it appears to be set up against a wall made of corrugated metal. All else is black. The camera cuts to a close-up of the curtains, which are parted to reveal a pale young man with crow’s nest hair wearing a sequined tuxedo and a skewed bow tie. The man holds a lit cigarette and behind him, overseeing proceedings, is a large statue of the Virgin Mary. As the man with the crow’s nest hair walks fully through the arch he opens his mouth and sings the words ‘As the snow flies, on a cold and grey Chicago morn another little baby child is born…’. The song continues with the singer alternately shuffling as if embarrassed by the attention of the camera and then holding his arms aloft in declamation or fixing the viewer with a steely gaze. -

CONSTITUTIONAL COURT of SOUTH AFRICA Case CCT 311/17 in the Matter Between: GELYKE KANSE First Applicant DANIËL JOHANNES ROSSOU

CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA Case CCT 311/17 In the matter between: GELYKE KANSE First Applicant DANIËL JOHANNES ROSSOUW Second Applicant PRESIDENT OF THE CONVOCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Third Applicant BERNARDUS LAMBERTUS PIETERS Fourth Applicant MORTIMER BESTER Fifth Applicant JAKOBUS PETRUS ROUX Sixth Applicant FRANCOIS HENNING Seventh Applicant ASHWIN MALOY Eighth Applicant RODERICK EMILE LEONARD Ninth Applicant and CHAIRPERSON OF THE SENATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH First Respondent CHAIRPERSON OF THE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Second Respondent UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Third Respondent Neutral citation: Gelyke Kanse and Others v Chairperson of the Senate of the University of Stellenbosch and Others [2019] ZACC 38 Coram: Mogoeng CJ, Cameron J, Froneman J, Jafta J, Khampepe J, Madlanga J, Mathopo AJ, Mhlantla J, Theron J, Victor AJ Judgments: Cameron J (unanimous): [1] to [51] Mogoeng CJ (concurring): [52] to [63] Froneman J (concurring): [64] to [98] Heard on: 8 August 2019 Decided on: 10 October 2019 Summary: Section 29(2) of the Constitution — “reasonably practicable” — constitutionality of the language policy of the University of Stellenbosch — Afrikaans as a medium of instruction – access to higher education Section 6 of the Constitution — protection and promotion of indigenous minority languages — diminished use and status ORDER On direct appeal from the High Court of South Africa, Western Cape Division, Cape Town: 1. Leave to appeal is granted. 2. The appeal is dismissed, with no order as to costs in this Court. 3. The costs orders in the High Court are set aside. 4. In their place is substituted: “There is no order as to costs.” 2 JUDGMENT CAMERON J (Mogoeng CJ, Froneman J, Jafta J, Khampepe J, Madlanga J, Mathopo AJ, Mhlantla J, Theron J and Victor AJ concurring): Introduction [1] At issue is the 2016 Language Policy (2016 Language Policy) of Stellenbosch University, the third respondent. -

Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010 1

© Lizzie Thynne, 2010 Indirect Action: Politics and the Subversion of Identity in Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s Resistance to the Occupation of Jersey Lizzie Thynne Abstract This article explores how Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore translated the strategies of their artistic practice and pre-war involvement with the Surrealists and revolutionary politics into an ingenious counter-propaganda campaign against the German Occupation. Unlike some of their contemporaries such as Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon who embraced Communist orthodoxy, the women refused to relinquish the radical relativism of their approach to gender, meaning and identity in resisting totalitarianism. Their campaign built on Cahun’s theorization of the concept of ‘indirect action’ in her 1934 essay, Place your Bets (Les paris sont ouvert), which defended surrealism in opposition to both the instrumentalization of art and myths of transcendence. An examination of Cahun’s post-war letters and the extant leaflets the women distributed in Jersey reveal how they appropriated and inverted Nazi discourse to promote defeatism through carnivalesque montage, black humour and the ludic voice of their adopted persona, the ‘Soldier without a Name.’ It is far from my intention to reproach those who left France at the time of the Occupation. But one must point out that Surrealism was entirely absent from the preoccupations of those who remained because it was no help whatsoever on an emotional or practical level in their struggles against the Nazis.1 Former dadaist and surrealist and close collaborator of André Breton, Tristan Tzara thus dismisses the idea that surrealism had any value in opposing Nazi domination.