Letter from Trinidad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and Their Use for Composition

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and their Use for Composition submitted by Georg Boenn for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Bath Department of Computer Science February 2011 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author. This thesis may not be consulted, photocopied or lent to other libraries without the permission of the author for 3 years from the date of acceptance of the thesis. Signature of Author . .................................. Georg Boenn To Daiva, the love of my life. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Musical Time and the Problem of Musical Form . 17 1.2 Context of Research and Research Questions . 18 1.3 Previous Publications . 24 1.4 Contributions..................................... 25 1.5 Outline of the Thesis . 27 2 Background and Related Work 28 2.1 Introduction...................................... 28 2.2 Representations of Musical Rhythm . 29 2.2.1 Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 29 2.2.2 The Piano-Roll Notation . 33 2.2.3 Necklace Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 34 2.2.4 Adjacent Interval Spectrum . 36 2.3 Onset Detection . 36 2.3.1 ManualTapping ............................... 36 The times Opcode in Csound . 38 2.3.2 MIDI ..................................... 38 MIDIFiles .................................. 38 MIDIinReal-Time.............................. 40 2.3.3 Onset Data extracted from Audio Signals . 40 2.3.4 Is it sufficient just to know about the onset times? . 41 2.4 Temporal Perception . -

The Haec Dies Gradual the Formulas and the Structure Pitches

68 The Haec dies Gradual The formulas and the structure pitches The primary structure pitches for recitation and accentuation are A (the Final of the mode) and C (the Dominant and a universal structure pitch). Punctuation occurs: 1) on A (the Final); 2) on C (the Dominant and universal structure pitch); 3) on F (the other universal structure pitch) and 4) on D (as a suspended cadence on the fourth above the Final). The first phrase (unique to this gradual): The structure pitches: -cc6côccc8cccc8ccccccccccc6ccccc Haec di- es, The initial structure pitch A is given a great deal of emphasis, both by the large Uncinus in Laon 239 and by the t (tenete = lengthen, hold) in the Cantatorium of St. Gall. It is followed by a rapidly moving ornament that circles the A much like the motion of a softball pitcher, in order to add momentum and intensity to the final A before ascending to C. The ornament ends with an Oriscus on the final A that builds the intensity even further until it reaches the C, the 69 climax of the entire melodic line over the word Haec. The tension continues over the accented syllable of the word di-es by means of the rapid, triple pulsation of the C, the Dominant of the piece. The melody then descends to A (the Final of the piece) and becomes a rapid alternation between A and G that swings forcefully to the last A on that syllable. The A is repeated for the final syllable of the word to produce a simple redundant cadence. -

Singing the Prostopinije Samohlasen Tones in English: a Tutorial

Singing the Prostopinije Samohlasen Tones in English: A Tutorial Metropolitan Cantor Institute Byzantine Catholic Metropolia of Pittsburgh 2006 The Prostopinije Samohlasen Melodies in English For many years, congregational singing at Vespers, Matins and the Divine Liturgy has been an important element in the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox churches of Southwestern Ukraine and the Carpathian mountain region. These notes describes one of the sets of melodies used in this singing, and how it is adapted for use in English- language parishes of the Byzantine Catholic Church in the United States. I. Responsorial Psalmody In the liturgy of the Byzantine Rite, certain psalms are sung “straight through” – that is, the verses of the psalm(s) are sung in sequence, with each psalm or group of psalms followed by a doxology (“Glory to the Father, and to the Son…”). For these psalms, the prostopinije chant uses simple recitative melodies called psalm tones. These melodies are easily applied to any text, allowing the congregation to sing the psalms from books containing only the psalm texts themselves. At certain points in the services, psalms or parts of psalms are sung with a response after each verse. These responses add variety to the service, provide a Christian “pointing” to the psalms, and allow those parts of the service to be adapted to the particular hour, day or feast being celebrated. The responses can be either fixed (one refrain used for all verses) or variable (changing from one verse to the next). Psalms with Fixed Responses An example of a psalm with a fixed response is the singing of Psalm 134 at Matins (a portion of the hymn called the Polyeleos): V. -

Protest and Pop Music SAMPLE

Protest and Pop Music First Year Seminar SAMPLE SYLLABUS THIS WILL NOT BE EXACTLY THE SAME Robert Bell Office: Bobet 115 Office Hours: MTW 9-10am [email protected] 865.3094 Brief Course Description: This course will look at the intersection of popular music and politics. From the earliest English ballads to today’s gangsta rap, protest music has played a central thematic role in popular culture. This class will explore the historical context of different time periods, songs and artists, and show how something apparently as benign as pop music actually expresses an underlying political dimension and identity. Texts: Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song , David Margolick [Ecco Press, 2001] Other readings TBD through Blackboard Goals and Learning Outcomes: Goal 1: Creative/Critical Thinking A: Define a problem B: Compile and assess evidence C: Build / refute arguments D: Draw evidence-based conclusions Goal 2: Effective Communication: Written Assignments & Oral Presentations A: Effectively present information B: Form conclusions based on pertinent information Goal 3: You and the Community A: Understand how the choices one makes work towards creating a community identity B: Help others understand how consummation relates to identity formation Requirements: 20 % Participation 5% Quizzes and homework 20% Blog 15% Paper 1—Protest Song in Praxis (The song as symptom) 15% Service Learning Project or Class Presentation 25% Final/Paper 2—Protest or just Pop? Participation —This class is discussion based; you will be required to participate actively in the class discussion and have read and/or listened to all the material assigned. Often you will be asked to do research before class and present that research to the class. -

Get Me Bodied Mp3

Get me bodied mp3 Get Me Bodied. Artist: Beyonce. MB · Get Me Bodied. Artist: Beyonce. MB · Get Me Bodied. Artist: Beyonce. Beyoncé's official video for 'Get Me Bodied' ft. Kelly Rowland, Michelle Williams and Solange Knowles. Buy Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix): Read 28 Digital Music Reviews - Nine, four, eight, one. B-Day Verse 1 mission one. Imma put this on. When he see me in the dress I'ma get me some (hey) mission two. Gotta make that call. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Beyoncé – Get Me Bodied for free. Get Me Bodied appears on the album B'Day. Discover more music, gig and. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Beyoncé – Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix) for free. Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix) appears on the album B'Day. Fabolous & NMC Feat. Beyonce Get Me Bodied free mp3 download and stream. Watch Get Me Bodied (Timbaland Remix) by Beyoncé online at Discover the latest music videos by. Beyonce – Get Me Bodied (Acapella). Artist: Beyonce, Song: Get Me Bodied (Acapella), Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, Type: mp3. Beyoncé's official video for 'Get Me Bodied' ft. Kelly Rowland, Michelle Williams and Solange Knowles (Timbaland Remix). Click to listen to Beyoncé on Spotify. Lyrics to song "Get Me 3" by Beyonce: Get Me Bodied by Beyonce 9 - 4- B-Day Verse 1 Mission One I'ma put this on When he see me in this dress. Beyonce – Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix) – 98 BPM. Categories: s, BPM, Pop. Audio Player. /audio/3. -

Music for a While’ (For Component 3: Appraising)

H Purcell: ‘Music for a While’ (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances Henry Purcell (1659–95) was an English Baroque composer and is widely regarded as being one of the most influential English composers throughout the history of music. A pupil of John Blow, Purcell succeeded his teacher as organist at Westminster Abbey from 1679, becoming organist at the Chapel Royal in 1682 and holding both posts simultaneously. He started composing at a young age and in his short life, dying at the early age of 36, he wrote a vast amount of music both sacred and secular. His compositional output includes anthems, hymns, services, incidental music, operas and instrumental music such as trio sonatas. He is probably best known for writing the opera Dido and Aeneas (1689). Other well-known compositions include the semi-operas King Arthur (1691), The Fairy Queen (1692) (an adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and The Tempest (1695). ‘Music for a While’ is the second of four movements written as incidental music for John Dryden’s play based on the story of Sophocles’ Oedipus. Dryden was also the author of the libretto for King Arthur and The Indian Queen and he and Purcell made a strong musical/dramatic pairing. In 1692 Purcell set parts of this play to music and ‘Music for a While’ is one of his most renowned pieces. The Oedipus legend comes from Greek mythology and is a tragic story about the title character killing his father to marry his mother before committing suicide in a gruesome manner. -

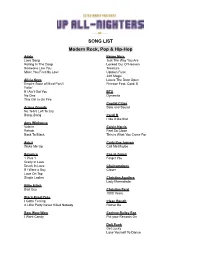

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

By Beyonce Knowles

© 2018 JETIR September 2018, Volume 5, Issue 9 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) ANALYSIS OF COMPLAINING STRATEGIES IN THE HOLLYWOOD SONG “IF I WERE A BOY” BY BEYONCE KNOWLES Dr. Amrita Tyagi Assistant Professor, Department of English, Galgotias University, Greater Noida Dr. Vijay Kumar Associate Professor, Department of English, Galgotias University, Greater Noida ABSTRACT -In this digital era, complaining has become so pervasive that it creeps into our conversations from the dinner table to our workplace. A complaint is incomplete without three main elements: a speaker, a listener, and a signaling system or language. Language plays a crucial part in our lives to inform people around us of what we feel, what we desire and question or understand the world around us. The fundamental function of language is communication. Songs are one of the greatest creations of human kind in the course of history. It is creativity in a pure and undiluted form and format. The speech act is an utterance considered as an action, particularly with regards to its intention, purpose or effect. Jane Austin claims that many utterances are equivalent to actions which means without performing an action by mere words action can be performed. Songs reflect the society, what’s present in the society creates an impact on the songs written by various songwriters and hence songs are incomplete without complaints, be it any romantic song, sad song or an inspiring one. Complaints can be found in every song about the lover, the world or the people. In this study, the lyrics of a Hollywood song “If I were a boy” by an American singer Beyonce Knowles has been used for the analysis of complaining act. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

The Derailment of Feminism: a Qualitative Study of Girl Empowerment and the Popular Music Artist

THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST A Thesis by Jodie Christine Simon Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2010 Bachelor of Arts. Wichita State University, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts July 2012 @ Copyright 2012 by Jodie Christine Simon All Rights Reserved THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. __________________________________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Chair __________________________________________________________ Jeff Jarman, Committee Member __________________________________________________________ Chuck Koeber, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my husband, my mother, and my children iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Jodie Hertzog, for her patient and insightful advice and support. A mentor in every sense of the word, Jodie Hertzog embodies the very nature of adviser; her council was very much appreciated through the course of my study. v ABSTRACT “Girl Power!” is a message that parents raising young women in today’s media- saturated society should be able to turn to with a modicum of relief from the relentlessly harmful messages normally found within popular music. But what happens when we turn a critical eye toward the messages cloaked within this supposedly feminist missive? A close examination of popular music associated with girl empowerment reveals that many of the messages found within these lyrics are frighteningly just as damaging as the misogynistic, violent, and explicitly sexual ones found in the usual fare of top 100 Hits. -

Various Artists: These Are the Breaks for Information and Soundclips of Our Titles, Go to Street Date: 02/14/2012

UBIQUITY RECORDS PRESENTS VARIOUS ARTISTS: THESE ARE THE BREAKS FOR INFORMATION AND SOUNDCLIPS OF OUR TITLES, GO TO WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM/PRESS STREET DATE: 02/14/2012 Jed and Lucia HELIUM EP “These Are The Breaks” is a collection of 1) Searching For Soul Part 1 – 2:39 12 original tracks from the Luv N’ Haight and 2) There's Nothing I Can Do About It – 2:34 Ubiquity catalogs that have been sampled by 3) Africana – 2:54 4) Gettin' Down – 2:40 well-known artists ranging in diversity from 5) Sweetest Thing In The World – 2:22 Beyonce to Beck. 6) Boys With Toys – 2:46 Jake Wade and The Soul Searchers (Searching For Soul) 7) Spread The News – 4:14 Searching For Soul Part 1 - Sampled by both Rich Harrison for 8) Hang On In There – 8:57 Beyonce’s “Suga Mama” and Madlib for Percee P’s “Legendary Lyricist” 9) Plenty Action – 2:53 10) Do Whatever Turns You On pt.2 – 2:40 Mike And The Censations (Don’t Sell Your Soul) There’s Nothing I 11) We Know We Have To Live Together – Can Do About It - Sampled and re-edited by Nicolas Jaar for his track “What My Last Girl Put Me Through” on his Bluewave Edits 5:49 12) Hold You Close – 6:17 The Propositions (Funky Disposition) Africana - Sampled on the “Outro” of the classic Souls of Mischief album ‘93 Til’ Infinity. Do Whatever Turns you On Pt.2 - Sampled on the Lupe Fiasco track “Gold Watch” Eugene Blacknell (We Can’t Take Life For Granted) Getting Down - CATALOG UBR11295-2 CATALOG UBR11295-1 Sampled by DJ Shadow on his track “Influx”. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co.