Tracing Ballet's Pedagogical Lineage in the Work of Maggie Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

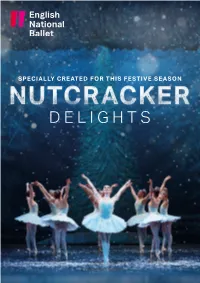

Nutcracker Delights

SPECIALLY CREATED FOR THIS FESTIVE SEASON DELIGHTS I A word from Tamara Rojo Welcome to Nutcracker Delights. I am And, finally, thank you to each of you joining us delighted that we are back on stage at the here for this festive celebration. We are so very This programme was designed for English London Coliseum and that we are once again happy to be able to share this space with you National Ballet’s planned season of Nutcracker able to share our work, live in performance, with again. I hope that you enjoy the performance. President Delights at the London Coliseum from you all. 17 December 2020 — 3 January 2021. Dame Beryl Grey DBE The extraordinary circumstances of 2020 have Chair As London moved into Tier 4 COVID-19 changed the way all of us work and live, and restrictions with the subsequent cancellation Sir Roger Carr I believe more strongly than ever in the power of all scheduled performances of Nutcracker Artistic Director of the arts to provide inspiration, shared Delights, the Company decided to film and Tamara Rojo CBE experience, hope, and solace. Tamara Rojo CBE share online, for free, a recording of this Artistic Director What a pleasure to mark our return to live specially adapted production as a gift to our Executive Director English National Ballet performance by continuing a Christmas fans at the close of our 70th Anniversary year. Patrick Harrison tradition we have held dear for 70 years. We have performed a version of Nutcracker Chief Operating Officer After a year that has been so difficult for so every year since the Company was founded, Grace Chan many, I am thrilled that we are able to bring and were determined to continue this much- Music Director some festive magic back to the stage. -

Old Owenians Newsletter June 2012 V2.Pdf

Old Owenians Newsletter Second Quarter 2012—27th June Edition 6 Welcome to our Old Owenians Newsletter—for all Old Owenians, with a message from our Head... “Dear Old Owenians With just over three weeks to go before the end of another school year, we say goodbye to some of our Year 11 and all our Year 13 students, wishing them best of luck and success with their results in August. We also welcome them as Old Owenians, hope they’ll keep in touch by reading our Old Owenians Newsletters and come back to join us at some of our 400th anniversary events next year. Perhaps they’ll revisit the school, as over 120 of you did for our highly successful first ever Old Owenians Coffee and Tour morning on Saturday 26th May—read more on pages 3 and 4! We were delighted that our school was represented on two significant Jubilee occasions by current and past students… ...our Deputy Head Girl, Alice Robinson, was honoured to be invited to attend the Westminster Hall celebration lunch with members of the Worshipful Company of Brewers (our school’s trustee), following the Diamond Jubilee Thanksgiving Service at St Paul’s Cathedral on Tuesday 5th June. It was hosted by the 108 Livery Companies of the City of London—around 700 guests and representatives of charities and the armed forces dined with members of the Royal Family. The Livery Companies originated in medieval times as Guilds responsible for trade regulation—today the Companies use their funds to undertake charitable and community work. Alice, whose name was drawn out of a hat for the opportunity to attend, comments on page 5. -

Alvin Ailey's Embodiment of African American Culture

DeFrantz.00 FM 10/20/03 2:50 PM Page ii Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture 1 2004 DeFrantz.00 FM 10/20/03 2:50 PM Page iii DANCING REVELATIONS THOMAS F. DEFRANTZ DeFrantz.00 FM 10/20/03 2:50 PM Page iv 1 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © 2004 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data DeFrantz, Thomas Dancing revelations : Alvin Ailey’s embodiment of African American culture / Thomas F. DeFrantz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-515419-3 1.Ailey, Alivn. 2. Dancers—United States—Biography. 3.Choreographers— United States—Biography. 4.Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. 5.African American dance. I. Title. GV1785.A38 D44 2003 792.8'028'092—dc21 2002156670 Credits: Photographs: frontispiece and pages 5, 8, 19, 47, 63, 95, 101 courtesy and copyright by Jack Mitchell; cover illustration and pages 11, 12,courtesy and copyright by J. -

The Inventory of the Alicia Markova Collection #1064

The Inventory of the Alicia Markova Collection #1064 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Markova, Alicia #1064 6/30/95 Preliminary Listing Box 1 I. Correspondence. [F. 1] A. Markova, Alicia. ANS to unknown, 1 p., n.d. B. Invitation to the annual meeting of the Boston University Friends of the Libraries where AM will speak, May 8, 1995. II. Printed Material. A. Newspaper clippings. 1. AMarkova Rounding Out 33 Years on Her Toes,@ by Art Buchwald, New York Herald Tribune, Nov. 22, 1953. [F. 2] 2. AThe Ballet Theatre,@ by Walter Terry, New York Herald Tribune, Apr. 16, 1955. 3. Printed photo of AM, Waterbury American, Nov. 25, 1957. 4. ATotal Role Recall,@ by Jann Parry, The Observer Review, Jan. 29, 1995. 5. AThe Nightingale Dances Again,@ by Ismene Brown, The Daily Telegraph, Feb. 3, 1995. 6. AA Step in Time,@ by David Dougill, The Sunday Times, Feb. 5, 1995. 7. AFanfare for Stars With a Place in Our Hearts,@ by Michael Owen, Evening Standard, Mar. 21, 1995. B. Photocopied pages from an unidentified printed source; all images of AM; 13 p. total. C. Promotional brochure for Yorkshire Ballet Seminars, July 29 - Aug. 26, 1995. D. Booklets. [F. 3] 1. AEnglish National Ballet,@ for a ARoyal gala performance in celebration of the 80th birthday of the President and co-founder of the company, Dame Alicia Markova ...,@ Nov. 27, 1990. 2. AA Dance Spectacular, in tribute to Dame Alicia Markova DBE, on the occasion of her 80th birthday ... in aid of The Dance Teachers= Benevolent Fund,@ Dec. 2, 1990. III. Photographs. -

Peter Brinson (Born Llandudno, Wales, 1923 - Died London, 1995)

IN MEMORIAM Peter Brinson (born Llandudno, Wales, 1923 - died London, 1995) Dance is.. .about the history of human movement, the history of human cul- ture and the history of human communication. Peter Brinson, lecturing in London at the Royal Society of Arts, March 1992 Those words, grand in scale yet spoken at the time with quiet modesty, serve now as an epitaph for what guided Peter Brinson. He was an idealist, an intellectual, and a man uniquely qualified by belief and experience to interact with dance (whether theoretical or practical), and dancers (whether professional or amateur). His mission, pursued through writing, lectur- ing and his prominence as a public figure, was to raise dance's status, and in doing so to help break down social, cultural and racial barriers. Believing all forms were valuable he made no distinction between high and low, for he wanted to take dance out of its ivory tower and make it a part of normal life. Dance, as he wrote in 1980, "does not take place in a vacuum: it arises from society expressing personal and social needs and is set in a real world of power, money, state structures, international influences and professional relationships" (1). Brinson was driven by convictions, first because he believed in the pursuit of knowledge as a means towards unlocking prejudice, and second because of the role he saw that the arts could play in bringing out the nobler side of mankind. Looking back now at his achievements, it is clear that in Britain his influence pervades dance's practices. -

Agnes De Mille Theatre Allet (1905 ~ 1993) Diana Byer, Artistic Directorbexquisite Little Ballets

N EW Y ORK Agnes de Mille theatre allet (1905 ~ 1993) diana byer, artistic directorbexquisite little ballets Agnes de Mille (September 18, 1905 – October 7, 1993) was an American dancer and choreographer. Her accomplishments to the the- ater have left an impression on the growth and resilience of theatrical dance as one sees it today. She developed her own style. She added lyricismN andEW comedy,Y ORK which is perceived as a divergence from the culturalthe dancea formstre of the era. Thosea aspectsll becameet her signature trademarksdiana byer, artistic seen indirector manyb of her best exquisiteknown littleand balletsbeloved works. de Mille was born in the Harlem section of New York City and Marked as her moved to Hollywood with her family. She aspired to become an most extensive phases Photo by Beryl actress, which seemed appropriate being that her uncle was the of dance training, her Towbin illustrious Hollywood filmmaker and director, Cecil B. de Mille. work with Marie Rambert at As it turned out, her desire to perform for the camera wasn’t Ballet Club proved to be highly significant. It was there that fully realized. She was told that she wasn’t “pretty enough.” she met emerging choreographers Frederick Ashton and Antony So, she studied and performed the piano and also staged drama Tudor who she’d later work with at American Ballet Theatre. productions. She then began studying dance, including ballet. Classical ballet was the most widely known form of dance at Throughout the 1930’s de Mille spent much of her time train- that time, but she lacked the physical attributes needed to have ing, but was never able to support herself as a dancer or cho- a career in classical ballet. -

From Dance Cultures to Dance Ecology: a Study of Developing Connections Across Dance Organisations in Edinburgh and North West England, 2000 to 2016

From dance cultures to dance ecology: a study of developing connections across dance organisations in Edinburgh and North West England, 2000 to 2016 Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Jamieson, Evelyn Citation Jamieson, E. C. (2016). From dance cultures to dance ecology: a study of developing connections across dance organisations in Edinburgh and North West England, 2000 to 2016 (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Download date 06/10/2021 00:37:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/620561 FROM DANCE CULTURES TO DANCE ECOLOGY: A STUDY OF DEVELOPING CONNECTIONS ACROSS DANCE ORGANISATIONS IN EDINBURGH AND NORTH WEST ENGLAND, 2000 TO 2016 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Evelyn Carnduff Jamieson 15th December 2016 FROM DANCE CULTURES TO DANCE ECOLOGY: A STUDY OF DEVELOPING CONNECTIONS ACROSS DANCE ORGANISATIONS IN EDINBURGH AND NORTH WEST ENGLAND, 2000 TO 2016 ABSTRACT The first part of this thesis provides an autobiographical reflection and three contextualising histories to illustrate the increasing codification of late twentieth century UK contemporary dance into discrete cultures. These are professional contemporary dance and professional performance, dance participation and communitarian intervention, and dance as subject for study and training. The central section of the thesis examines post-millennial reports and papers by which government, executives and public sector arts organisations in both England and Scotland have sought to construct and steer dance policy toward greater collaborative connections on financial and ideological grounds. This is contrasted with a theoretical consideration of collaboration drawing on a range of academic approaches to consider the realities and ideals of creative and artistic collaboration and organisational collaboration. -

Patricia Ruanne: a Conversation with a Ballet Répétiteur by Bill Bissell

QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE Patricia Ruanne: A Conversation with a Ballet Répétiteur By Bill Bissell THE PEW CENTER FOR ARTS & HERITAGE / PCAH.US / @PEWCENTER_ARTS Patricia Ruanne: A Conversation with a Ballet Répétiteur AN INTERVIEW BY BILL BISSELL Introduction Patricia Ruanne is concerned with the abiding aesthetic and ethical values that constitute ballet as an art form. In this world, artistic values are informed by aesthetics as well as ethics. Her impressive record as a dance artist—as performer, coach, ballet mistress, répétiteur—has yielded a remarkable career. Ruanne’s articulate assessment of the European ballet scene is framed by her early years spent in the Royal Ballet schools and companies, the 1960s through the early 1980s—a period marked by prolific creativity and strong performing personalities—as well as by her long and formative working association with Rudolf Nureyev. Patricia Ruanne’s dance pedigree was attained at England’s Royal Ballet schools at White Lodge and Baron’s Court. Her career ranges over an impressive roster of performing credits that includes contracts with the Royal Ballet and Royal Ballet Touring companies, London Festival Ballet (now English National Ballet), and many guest appearances on numerous projects and tours, several of which were gathered together as vehicles for Nureyev. A turning point in Ruanne’s career as a dancer came dance advance when Nureyev selected her to create the role of Juliet in his landmark production of Romeo and Juliet. Patricia Ruanne in a performance with London Festival Ballet, no date or information 2002 marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of this on production, possibly Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty. -

Interview with Gillian Lynne

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Gillian Lynne – interview transcript Interviewer: Sue Barbour 22 March 2010 Dancer and Choreographer. Acting; David Albery; A Midsummer Night's Dream; BBC; Broadway; Rudolph Cartier; Cats; choreography; Cone Ripman School; Bernard Delfont; digs; Five Past Eight; Errol Flynne; Margot Fonteyn; John Gilpin; Pauline Grant; Robert Helpmann; jazz ballet; Molly Lake; Jacques Lecoq; Andrew Lloyd Webber; London Palladium; Leonide Massine; David Merrick; modern dance; Dudley Moore; musicals; opera; Peter and the Wolf; repertory; revue; Sadler's Wells Ballet; Symphonic Variations; The Three-cornered Hat; Dame Ninette de Valois; variety. SB: This is Sue Barbour with the University of Sheffield. I’m interviewing Gillian Lynne, and first of all Gillian I’d like to ask you if you are in agreement with this interview being used for the British Library Theatre Project and for future generations to learn about Variety Theatre? GL: Yes, I’m very, very proud. Very proud. SB: First of all I’d like to ask you where you were born and brought up? GL: I was born in Bromley, Kent and my ancestors had all been living in Kent and I was brought up all over the place because when we got to 1939, when I was, I think, twelve, and my mother was killed in a terrible car crash, so that I had… Very quickly the war came and my Dad – I was an only child – and suddenly I had nothing because my Dad, like everybody who had been in the First World War, was immediately sucked up into the army and he had been a Captain in the First World War, caught, kept prisoner and all that sort of thing. -

Canty, Graham To

INSIDE THIS ISSUE .. • Philip Hart Memoriam ... page 5 • Affirmative Action Challenge .. , .. page 2 • Hoyas Walk Navy's Plank. page 8. 57th Year, No. 14 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D.C. Friday, January 14, 1977 Ex -G UProf Carroll Ouigley Bailey Named Speaker Dies of Heart Attack at 66 . by Tracey Hughes Princeton and as a goyernment, Carter Will Be Invited Retired Georgetown University history and politics tutor at Harvard Spokesmen for Carter say that the Bailey was not on the poll of History Professor Dr. Carroll Quigley before coming to Georgetown. by Bart Saitta president-elect is not yet considering senior choices for graduation speaker died January 3rd at University He is survived by his wife Lillian Entertainer Pearl Bailey and pas· invitations speak at universities taken by the Senior Week committee Hospital after suffering a heart and two sons, Dennis and Thomas. sibly, Jimmy Carter will address ihis to and that he will not determine his which was led by Art Buchwald and attack. Dr. Quigley, who was 66, A fund to endow a professorship year's graduating class at the May May schedule "for a couple of Woody Allen. Buchwald and Allen retired last June after 35 years of in Quigley's name was founded this 22nd commencement. months." The chances of Carter declined to speak as did Barbara teaching at Georgetown. fall and the family requests that The University is sending a formal spealting at Georgetown are not Jordan, the students' third choice. expressions of sympathy be made in invitation to Carter according to Quigley, who came to George Commenting on the fact that the form of contributions to the Charles Men assistant to the Univer considered likely by those close to town in 1941, was awarded the the selection of the graduation Bailey was not one of the poll University's Vicennial Medal in 1961 fund, now entitled the Carroll Quig. -

Restaging the Ballets of Antony Tudor A

PRESERVING A LEGACY, PRESERVING BALLET HISTORY: RESTAGING THE BALLETS OF ANTONY TUDOR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF DANCE COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY CHRISTINE KNOBLAUCH-O’NEAL A.B., M.A.L.S. DENTON, TEXAS MAY 2013 [Type a quotei from the document or the summary of an interesting point. You can position the text box anywhere in the Copyright © Christine Knoblauch-O’Neal, 2013 all rights reserved iii DEDICATION To Grant and Kathleen Knoblauch, they were the best parents. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to gratefully acknowledge the many individuals who have contributed to this dissertation. I would like to thank my committee chair Dr. Linda Caldwell for her continued interest in this research. I want to thank Sally Bliss executor of the Tudor will and Trustee of the Antony Tudor Ballet Trust for allowing me full access to the Trust and to the Répétiteurs of the Trust who participated in my research. The research could not have been completed without her continued interest and support of this project. I am grateful to both Dr. Janet Brown and Betty Skinner for their continued encouragement and guidance during my beginning efforts to create a document worthy of the topic. In particular, I want to thank my sister Karen Brewington for her continued support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies. All scholars should be fortunate enough to have sisters like Karen. And, finally, I want to thank Mike Lang for being there for me during every moment of my doctoral studies, listening to me, challenging me, and encouraging me to feel confident in my work. -

Baller Fontey Specia

FONTEYN Ballerina assoluta, fashion heroine and RAD President, Margot ICONFonteyn was the ultimate ballet icon. To open our centenary special, Anna Winter traces her unique impact on dance. FONTEYN Ballerina assoluta, fashion heroine and RAD President, Margot ICONFonteyn was the ultimate ballet icon. To open our centenary special, Anna Winter traces her unique impact on dance. Peggy Hookham was a solemn little girl with a thick page-boy haircut, a pet chipmunk and a penchant for vigorous character dance. Born 100 years ago in Reigate, Surrey, she was no starry-eyed Pavlova-in-waiting. While Frederick Ashton proclaimed that the itinerant Russian ballerina ‘injected me with her poison’ at first sight and compelled him to dance, a Pavlova performance made little impression on the grave-eyed girl who would become Britain’s prima ballerina assoluta. Yet by her teenage years, Peggy Hookham had been singled out by the formidable Ninette de Valois as the prized practitioner of the fledgling British ballet. Her identity changed at de Valois’ bidding – the more glam- orous moniker filched from a London hairdresser, one entry along in the telephone book from Mrs Hookham’s Brazilian maiden name of Fontes. Since Peggy’s mother had been born illegitimately to an Irish mother, the well-to-do Fontes family refused to lend their name to the burgeoning bal- lerina of the Vic-Wells company. So Peggy Hookham became Margot Fonteyn, transforming over the years into Ashton’s muse, custodian of the Petipa classics and an interna- tional star known way beyond balletic enclaves. What was it that made this dancer in particular – and not her talent- ed peers – such an icon? After all, her ‘bad feet’ and relative lack of virtuos- ity have been written about at length.