Integrating Physical and Behavioral Health Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AAFP Letter to CMS on Prior Authorizations in Medicare

February 28, 2019 The Honorable Seema Verma Administrator Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Hubert H. Humphrey Building, Room 445–G 200 Independence Avenue, SW Washington, DC 20201 Dear Administrator Verma: The undersigned organizations are writing to urge the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide guidance to Medicare Advantage (MA) plans on prior authorization (PA) processes through its 2020 Call Letter. CMS’ guidance should direct plans to target PA requirements where they are needed most. Specifically, CMS should require MA plans to selectively apply PA requirements and provide examples of criteria to be used for such programs, including, for example, ordering/prescribing patterns that align with evidence- based guidelines and historically high PA approval rates. At a time when CMS has prioritized regulatory burden reduction in the patient-provider relationship through its Patients Over Paperwork initiative, we believe such guidance will help promote safe, timely, and affordable access to care for patients; enhance efficiency; and reduce administrative burden on physician practices. A Consensus Statement on Improving the Prior Authorization Process, issued by the AMA, the American Hospital Association, America’s Health Insurance Plans, the American Pharmacists Association, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and the Medical Group Management Association in January 2018, identified opportunities to improve the prior authorization process, with the goals of promoting safe, timely, and affordable access to evidence-based care for patients; enhancing efficiency; and reducing administrative burdens.1 It notes that the PA process can be burdensome for all involved—health care providers, health plans, and patients—and that plans should target PA requirements where they are needed most. -

American Medical Association Resident and Fellow Section

MEDICAL SOCIETY OF DELAWARE COUNCIL Resolution: 01 (A-19) Introduced by: Psychiatric Society of Delaware Neil S. Kaye, MD, DLFAPA Subject: Commitment to Ethics Whereas, The medical profession has adhered to a Code of Ethics since the 5th Century BCE; and Whereas, Such Codes have included the Oath of Hippocrates and the Oath of Maimonides; and Whereas, In 1803 Thomas Percival introduced our country’s first medical ethics standards; and Whereas, These codes were adopted by the AMA in 1847; and Whereas, The Code of Medical Ethics has been revised continuously, most recently in 2016; and Whereas, Forces from both within the house of medicine and outside of the house of medicine continually try to influence the practice of medicine; and Whereas, What has never changed in any of these ethical codes is the requirement that physicians focus 100% of their efforts on healing; therefore be it RESOLVED, That the Medical Society of Delaware will continue to recognize the AMA Code of Medical Ethics as binding on all decisions made by the organization and its members; and be it further RESOLVED, That the Medical Society of Delaware will actively resist all attempts to lessen its ethical standards as enumerated in the AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Fiscal Note: Undetermined 1American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2017 MEDICAL SOCIETY OF DELAWARE COUNCIL Resolution: 02 (A-19) Introduced by: Robert J. Varipapa, MD Subject: MSD Support of Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) -

State Medical Society Membership Requirements

State Medical Society Membership Requirements State Medical Society Representation‐ Updated June 2013 Recently, ASAM staff contacted each state medical society requesting required procedures for ASAM chapters to obtain official membership in the medical society’s governing body. Below are the responses received – Alaska: ASMA’s current bylaws call for House of Delegate members to be elected by the local medical society. There is no representation of specialty societies within the House of Delegates. Arizona: A state specialty or subspecialty society with 250 or fewer members shall be entitled to representation in the House of Delegates by one delegate and a specialty or subspecialty society with more than 250 members shall be entitled to 2 delegates if (1) the specialty or subspecialty is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties; (2) the specialty or subspecialty society has a minimum of twenty members practicing in Arizona; (3) the specialty or subspecialty society maintains an existing organization or structure with a slate of periodically elected officers, a constitution and bylaws and a frequency of meeting at least once a year; (4) by a vote of the House it shall be deemed to be in the best interests of the Association. Specialty or subspecialty society delegates shall be the society president or designee(s) who shall be members of the Association (http://www.azmed.org/arma‐governance). California: Each statewide specialty organization recognized by the House of Delegates shall be entitled to one (1) delegate and one (1) alternate. Specialty organizations having five hundred (500) or more members who are regular active members of CMA shall have one (1) additional delegate and alternate, plus one additional delegate and alternate for each full five hundred (500) members thereafter who are regular active members of CMA. -

July 22, 2020 the Honorable Seema Verma Administrator Centers For

July 22, 2020 The Honorable Seema Verma Administrator Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Hubert H. Humphrey Building, Room 445-G 200 Independence Avenue, SW Washington, DC 20201 Dear Administrator Verma: The undersigned organizations represent the hundreds of thousands of physicians who provide care for our nation’s Medicare patients every day. We are writing to strongly support the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) decision to temporarily waive certain regulatory requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. These temporary waivers, in extraordinary circumstances, have empowered physicians and non-physician health care professionals to focus on their patients and prevented a collapse of the health care system in the hardest hit areas of the country. However, we urge CMS to sunset the waivers involving scope of practice and licensure when the public health emergency (PHE) concludes. To our dismay, it is our understanding that some organizations have already been advocating to make the temporary waivers permanent—permanently diminishing physician oversight and supervision of patient care. While we are greatly appreciative of CMS’ rapid and substantial removal of regulatory barriers to allow physicians to continue providing care during the PHE, we also strive to continue to work with CMS to support patient access to physician-led care teams during and after the PHE. Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, physicians, nurses, and the entire health care community have been working side-by-side caring for patients and saving lives. Now more than ever, we need health care professionals working together as part of physician-led health care teams. -

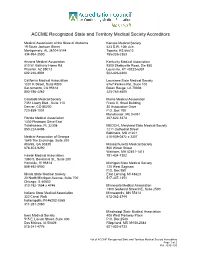

ACCME Recognized State and Territory Medical Society Accreditors

ACCME Recognized State and Territory Medical Society Accreditors Medical Association of the State of Alabama Kansas Medical Society 19 South Jackson Street 623 S.W. 10th Ave. Montgomery, AL 36104-5144 Topeka, KS 66612 334-954-2500 785-235-2383 Arizona Medical Association Kentucky Medical Association 2401 West Peoria Avenue, Suite 130 9300 Shelbyville Road, Ste 850 Phoenix, AZ 85029-4790 Louisville, KY 40222-6301 602-347-6900 502-426-6200 California Medical Association Louisiana State Medical Society 1201 K Street, Suite #800 6767 Perkins Rd., Suite 100 Sacramento, CA 95814 Baton Rouge, LA 70808 800-786-4262 225-763-8500 Colorado Medical Society Maine Medical Association 7351 Lowry Blvd., Suite 110 Frank O. Stred Building Denver, CO 80230 30 Association Drive 720-859-1001 P.O. Box 190 Manchester, ME 04351 Florida Medical Association 207-622-3374 1430 Piedmont Drive East Tallahassee, FL 32308 MEDCHI, Maryland State Medical Society 850-224-6496 1211 Cathedral Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Medical Association of Georgia 410-539-0872 x 3307 1849 The Exchange, Suite 200 Atlanta, GA 30339 Massachusetts Medical Society 678-303-9290 860 Winter Street Waltham, MA 02451-1411 Hawaii Medical Association 781-434-7302 1360 S. Beretania St., Suite 200 Honolulu, HI 96814 Michigan State Medical Society 808-692-0900 120 West Saginaw P.O. Box 950 Illinois State Medical Society East Lansing, MI 48823 20 North Michigan Avenue, Suite 700 517-337-1351 Chicago, IL 60602 312-782-1654 x 4746 Minnesota Medical Association 1300 Godward Street NE, Suite 2500 Indiana State Medical Association Minneapolis, MN 55413 322 Canal Walk 612-362-3744 Indianapolis, IN 46202-3268 317-261-2060 Mississippi State Medical Association Iowa Medical Society 408 West Parkway Place 515 E. -

March 25, 2015 the Honorable John A

March 25, 2015 The Honorable John A. Boehner The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives United States Senate H-232 U.S. Capitol S-230 U.S. Capitol Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20510 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Harry Reid Democratic Leader Democratic Leader U.S. House of Representatives United States Senate H-204 U.S. Capitol S-221 U.S. Capitol Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Speaker Boehner, Leader Pelosi, Majority Leader McConnell and Leader Reid: The American Medical Association and the undersigned state medical associations are pleased to offer our strong support for H.R. 2, the “Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act” (MACRA), and we urge all members of the House and Senate to support its immediate passage. This legislation represents years of bipartisan effort to eliminate the fatally flawed sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula and implement new payment and delivery models that will promote high-quality care while reducing costs. In addition to stabilizing the Medicare program for our nation’s seniors, MACRA takes a balanced approach to addressing the health care needs of children and low-income Americans while promoting the long-term sustainability of the Medicare program. We are encouraged by the bipartisan leadership and collaboration that produced this legislation, and urge all members of the House and Senate to support passage before the expiration of the current Medicare patch. Sincerely, American Medical Association Medical Association of the -

ACCME Recognized State Medical Societies

ACCME Recognized State Medical Societies Medical Association of the State of Alabama Arizona Medical Association 19 South Jackson Street 810 W. Bethany Home Rd. Montgomery, AL 36104-5144 Phoenix, AZ 85013 334-954-2500 602-246-8901 California Medical Association Colorado Medical Society Institute for Medical Quality 7351 Lowry Blvd. 180 Howard Street, Suite 210 Suite 110 San Francisco, CA 94105 Denver, CO 80230 415-882-5165 720-859-1001 Connecticut State Medical Society Florida Medical Association 127 Washington Ave. East Bldg, 3rd Fl 1430 Piedmont Drive East North Haven, CT 06473 Tallahassee, FL 32308 203-865-0587 850-224-6496 Medical Association of Georgia Hawaii Medical Association 1849 The Exchange 1360 S. Beretania St., Suite 200 Suite 200 Honolulu, HI 96814 Atlanta, GA 30339 808-692-0900 678-303-9290 Idaho Medical Association Illinois State Medical Society 305 Jefferson 20 North Michigan Avenue P.O. Box 2668 Suite 700 Boise, ID 83701 Chicago, IL 60602 208-344-7888 312-782-1654 x 4746 Indiana State Medical Association Iowa Medical Society 322 Canal Walk 515 E. Locust Street, Suite 400 Indianapolis, IN 46202-3268 Des Moines, IA 50309 317-261-2060 515-241-4776 Kansas Medical Society Kentucky Medical Association 623 S.W. 10th Ave. 9300 Shelbyville Road Topeka, KS 66612 Ste 850 785-235-2383 Louisville, KY 40222-6301 502-426-6200 August 14, 2017 Page 1 of 3 ACCME Recognized State Medical Societies Louisiana State Medical Society Maine Medical Association 6767 Perkins Rd. Frank O. Stred Building Suite 100 30 Association drive, P.O. Box 190 Baton Rouge, LA 70808 Manchester, ME 04351 225-763-8500 207-622-3374 MEDCHI, Maryland State Medical Society Massachusetts Medical Society 1211 Cathedral Street 860 Winter Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Waltham, MA 02451-1411 410-539-0872 x 3307 781-434-7302 Michigan State Medical Society Minnesota Medical Association 120 West Saginaw 1300 Godward Street NE P.O. -

ACCME Recognized State and Territory Medical Society Accreditors

ACCME Recognized State and Territory Medical Society Accreditors Medical Association of the State of Alabama Kansas Medical Society 19 South Jackson Street 623 S.W. 10th Ave. Montgomery, AL 36104-5144 Topeka, KS 66612 334-954-2500 785-235-2383 Arizona Medical Association Kentucky Medical Association 810 W. Bethany Home Rd. 9300 Shelbyville Road, Ste 850 Phoenix, AZ 85013 Louisville, KY 40222-6301 602-246-8901 502-426-6200 California Medical Association Louisiana State Medical Society 1201 K Street, Suite #800 6767 Perkins Rd., Suite 100 Sacramento, CA 95814 Baton Rouge, LA 70808 800-786-4262 225-763-8500 Colorado Medical Society Maine Medical Association 7351 Lowry Blvd., Suite 110 Frank O. Stred Building Denver, CO 80230 30 Association Drive 720-859-1001 P.O. Box 190 Manchester, ME 04351 Florida Medical Association 207-622-3374 1430 Piedmont Drive East Tallahassee, FL 32308 MEDCHI, Maryland State Medical Society 850-224-6496 1211 Cathedral Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Medical Association of Georgia 410-539-0872 x 3307 1849 The Exchange, Suite 200 Atlanta, GA 30339 Massachusetts Medical Society 678-303-9290 860 Winter Street Waltham, MA 02451-1411 Hawaii Medical Association 781-434-7302 1360 S. Beretania St., Suite 200 Honolulu, HI 96814 Michigan State Medical Society 808-692-0900 120 West Saginaw P.O. Box 950 Illinois State Medical Society East Lansing, MI 48823 20 North Michigan Avenue, Suite 700 517-337-1351 Chicago, IL 60602 312-782-1654 x 4746 Minnesota Medical Association 1300 Godward Street NE, Suite 2500 Indiana State Medical Association Minneapolis, MN 55413 322 Canal Walk 612-362-3744 Indianapolis, IN 46202-3268 317-261-2060 Mississippi State Medical Association Iowa Medical Society 408 West Parkway Place 515 E. -

July 16, 2019 the Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr. the Honorable Greg

July 16, 2019 The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr. The Honorable Greg Walden Chairman Ranking Member Committee on Energy and Commerce Committee on Energy and Commerce 2125 Rayburn House Office Building 2322A Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Chairman Pallone and Ranking Member Walden: The undersigned organizations believe a fair and equitable independent dispute resolution (IDR) process is an essential component of any surprise billing solution and should be included in any final bill coming out of the House Energy and Commerce Committee to ensure the legislation is balanced and does not result either in unfair payments to physicians or unreasonable bills to health plans. We fully support the central goal of the No Surprises Act to protect patients from surprise medical bills when they unknowingly receive services from out-of-network providers in in-network facilities. We also support the provisions in the No Surprises Act that would ensure patients are only responsible for in-network cost-sharing in these situations, and that their cost-sharing count toward in-network deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums. We also agree that patients should be taken out of any payment disputes between physicians and insurers that arise from these situations. However, once the patient is protected from surprise medical bills, it is equally important to ensure that the legislation does not create new imbalances in the private health care marketplace by undermining the ability of doctors to secure fair reimbursement for their services. The health insurance marketplace is already heavily consolidated. Instituting a federal government rate-setting scheme that allows private insurers to force discounted rates on physicians, hospitals and other health care providers based on their median 2019 in-network rates puts both network and non-network providers at a disadvantage and will result in sudden drops in reimbursement for emergency and nonemergency hospital-based care. -

Fs and Ethical with No Clear Consensus

Medical Professional Associations that Recognize Medical Aid in Dying A growing number of national and state medical organizations have endorsed or adopted a neutral position regarding medical aid in dying as an end-of-life option for mentally capable, terminally ill adults. Physician Support for Medical Aid in Dying Is Strong Medscape Poll, December 20161 A December 2016 Medscape poll of more than 7,500 U.S. physicians from more than 25 specialties demonstrated a significant increase in support for medical aid in dying from 2010. lethal doses of medications,”31% “strongly” Today well over half (57%) of the physicians supported this end-of-life care option. surveyed endorse the idea of medical aid in dying, agreeing that “Physician assisted death should be allowed for terminally ill patients.” The Maryland State Medical Society (MedChi) survey, June-July 20163 The Colorado Medical Society Member ➔ Six out of 10 Maryland physicians (60%) Survey, February 20162 supported changing the Maryland State ➔ Overall, 56% of CMS members are in favor of Medical Society’s position on Maryland’s “physician-assisted suicide, where adults in 2016 aid-in-dying legislation from opposing Colorado could obtain and use prescriptions the bill to supporting it (47%) or adopting a from their physicians for self-administered, neutral stance (13%). ➔ Among the physicians surveyed who were current members of the Maryland State Medical Society, 65 percent supported 1 Medscape Ethics Report 2016: Life, Death, and Pain, changing the organization’s position to December 23, 2016. Available from supporting the aid-in-dying bill (50.2%) or http://www.medscape.com/features/ slideshow/ethics2016-part2#page=2 adopting a neutral stance (14.6%). -

State Medical Associations and National Medical Specialty Societies

STATE MEDICAL ASSOCIATIONS AND NATIONAL MEDICAL SPECIALTY SOCIETIES April 15, 2021 President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20500 RE: Support for Richard Pan, M.D., for Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Administrator Dear President Biden, The undersigned State Medical Associations and National Specialty Societies are writing to offer our strong support for physician and State Senator Richard Pan’s candidacy for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Administrator position. As a practicing pediatrician and current state Senator in the California Legislature, Dr. Pan is a highly respected national health care leader who has championed public health and worked to improve health care disparities his entire career. Dr. Pan’s accomplishments and experience with the programs under HRSA make him uniquely qualified to lead the agency. Moreover, he would be a great asset to the Biden-Harris Administration’s initiatives to ensure that all Americans, particularly those in underserved communities of color, have access to the COVID-19 vaccine. As a physician, Dr. Pan cares for Medicaid and uninsured families and continues to practice at a community clinic while serving in California’s full-time state Legislature. As an educator and researcher, he has focused his efforts on addressing health care disparities and social determinants of health, including the creation of a medical training program that requires physicians and other health professionals to partner with communities to address health care disparities. He has also promoted health care workforce diversity to serve traditionally underserved communities. As a state Senator, Dr. Pan authored the nation’s first law to eliminate non-medical exemptions for childhood vaccines required for school. -

Neurosurgery Joins Multi-Specialty Letter Objecting to CMS Proposal

June 11, 2020 The Honorable Seema Verma Administrator Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Hubert H. Humphrey Building, Room 445-G 200 Independence Avenue, SW Washington, DC 20201 Re: File Code CMS-1729-P Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System for Federal Fiscal Year 2021 Proposal to Allow Non-physician Practitioners to Perform Certain IRF Coverage Requirements that Are Currently Required to Be Performed by a Rehabilitation Physician Dear Administrator Verma: The undersigned organizations write in response to a proposal included in the Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF) Prospective Payment System (PPS) proposed rule. In this rule, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) proposes to amend regulations to allow the use of non-physician practitioners (NPPs) to perform the IRF services and documentation requirements currently required to be performed by rehabilitation physicians under 42 CFR § 412.622. As representatives of the patients who require high-quality IRF-level care, as well as the clinicians and institutions that furnish services to the broader Medicare population, the undersigned organizations write to express our concerns that this proposal will undermine delivery of and access to physician-led team-based care in the IRF setting, which is critical for both ensuring the health and safety of patients receiving specialized rehabilitation care and differentiating the services that IRFs provide. We also are concerned that this sets a dangerous precedent for removing physician supervision requirements across all health care settings. For the reasons we further outline below, we strongly oppose this proposal to expand the scope of services NPPs furnish in IRFs, and we urge CMS to uphold the role of the rehabilitation physician in delivering and overseeing care for patients in IRF settings.