Genetically Modified Organisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steward : 75 Years of Alberta Energy Regulation / the Sans Serif Is Itc Legacy Sans, Designed by Gordon Jaremko

75 years of alb e rta e ne rgy re gulation by gordon jaremko energy resources conservation board copyright © 2013 energy resources conservation board Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication ¶ This book was set in itc Berkeley Old Style, designed by Frederic W. Goudy in 1938 and Jaremko, Gordon reproduced in digital form by Tony Stan in 1983. Steward : 75 years of Alberta energy regulation / The sans serif is itc Legacy Sans, designed by Gordon Jaremko. Ronald Arnholm in 1992. The display face is Albertan, which was originally cut in metal at isbn 978-0-9918734-0-1 (pbk.) the 16 point size by Canadian designer Jim Rimmer. isbn 978-0-9918734-2-5 (bound) It was printed and bound in Edmonton, Alberta, isbn 978-0-9918734-1-8 (pdf) by McCallum Printing Group Inc. 1. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. Book design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. 2. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board — History. 3. Energy development — Government policy — Alberta. 4. Energy development — Law and legislation — Alberta. 5. Energy industries — Law and legislation — Alberta. i. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. ii. Title. iii. Title: 75 years of Alberta energy regulation. iv. Title: Seventy-five years of Alberta energy regulation. hd9574 c23 a4 j37 2013 354.4’528097123 c2013-980015-8 con t e nt s one Mandate 1 two Conservation 23 three Safety 57 four Environment 77 five Peacemaker 97 six Mentor 125 epilogue Born Again, Bigger 147 appendices Chairs 154 Chronology 157 Statistics 173 INSPIRING BEGINNING Rocky Mountain vistas provided a dramatic setting for Alberta’s first oil well in 1902, at Cameron Creek, 220 kilometres south of Calgary. -

International Review of Environmental History: Volume 5, Issue 1, 2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction James Beattie 1 Nature’s revenge: War on the wilderness during the opening of Brazil’s ‘Last Western Frontier’ Sandro Dutra e Silva 5 Water as the ultimate sink: Linking fresh and saltwater history Simone M. Müller and David Stradling 23 Climate change: Debate and reality Daniel R. Headrick 43 Biofuels’ unbalanced equations: Misleading statistics, networked knowledge and measured parameters Kate B. Showers 61 ‘To get a cargo of flesh, bone, and blood’: Animals in the slave trade in West Africa Christopher Blakley 85 Providing guideline principles: Botany and ecology within the State Forest Service of New Zealand during the 1920s Anton Sveding 113 ‘Zambesi seeds from Mr Moffat’: Sir George Grey as imperial botanist John O’Leary 129 INTRODUCTION JAMES BEATTIE Victoria University of Wellington; Research Associate Centre for Environmental History The Australian National University; Senior Research Associate Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg This first issue of 2019 speaks to the many exciting dimensions of environmental history. Represented here is environmental history’s great breadth, in terms of geographical scope (Brazil, the Atlantic world, Europe, global, Africa and New Zealand); topics (animal studies, biography, climatological analysis, energy and waste); and temporal span (from the early modern to the contemporary period). The first article, ‘Nature’s revenge: War on the wilderness during the opening of Brazil’s “Last Western Frontier”’, explores the ongoing trope of the frontier and ‘frontiersman’ in the environmental history of twentieth-century Amazonia, Brazil. The author, Sandro Dutra e Silva, does so by skilfully analysing the creation of the heroic image of the road-building engineer Bernardo Sayão, and his deployment by the state to underpin its aims of developing Amazonia. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Religion of Science-Fantasy Cults Martin Gardner

Summer 1987 Vol. 7, No. 3 .40,11 Was the Universe Created? Victor Stenger The New Religion of Science-Fantasy Cults Martin Gardner The Relativity of Biblical Ethics Joe Edward Barnhart Plus "Pearlygate" Morality • New Directions for Humanism • Personal Paths to Humanism with Joseph Fletcher, Anne Gaylor, Rita Mae Brown, Ashley Montagu, and Mario Bunge • Tyranny of the Creed by John Allegro _- FreeC SUMMER 1987, VOL. 7, NO. 3 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 9 PERSPECTIVE 10 ON THE BARRICADES 61 IN THE NAME OF GOD 62 CLASSIFIED 6 EDITORIALS "Pearlygate" Morality Paul Kurtz / New Directions for Humanism / Catholic Consistency at Any Cost Tom Flynn 12 The Tyranny of the Creed John Allegro BELIEF AND UNBELIEF AROUND THE WORLD 14 Japan and Biblical Religion Richard L. Rubenstein 21 Letter to a Missionary Ronn Nadeau ARTICLES 22 The Relativity of Biblical Ethics Joe Edward Barnhart 25 Xenoglossy and Glossolalia Don Laycock 26 Was the Universe Created? Victor Stenger 31 Science-Fantasy Religious Cults Martin Gardner PERSONAL PATHS TO HUMANISM 36 A Secular Humanist Confession Joseph Fletcher 37 Free from Religion Anne Nicol Gay!or 38 Surrender to Life Rita Mae Brown 40 As if Living and Loving Were One Ashley Montagu 42 Growing Up Agnostic in Argentina Mario Bunge 46 The Case Against Reincarnation (Part 4) Paul Edwards BOOKS 54 The Cult of Objectivism Nathaniel Branden 55 Propaganda Before Education Gordon Stein 56 Critiquing the Old Unities Robert Basil Rita Mae Brown's and Ashler Montagu's articles are adapted by permission from The Courage of Conviction, edited by Philip Berman, published in hardcover by Dodd, Mead, and Company and in paperback by Ballantine Books. -

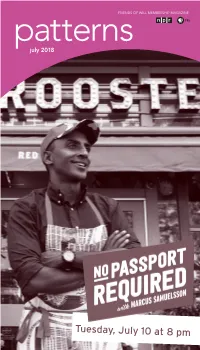

PDF Version of July 2018 Patterns

FRIENDS OF WILL MEMBERSHIP MAGAZINE patterns july 2018 Tuesday, July 10 at 8 pm WILL-TV TM patterns Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 july 2018 Volume XLVI, Number 1 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801-2316 Mailing List Exchange Donor records are proprietary and confidential. WILL does not sell, rent or trade its donor lists. Patterns Friends of WILL Membership Magazine Editor/Art Designer: Sarah Whittington Printed by Premier Print Group. Printed with SOY INK on RECYCLED, TM Trademark American Soybean Assoc. RECYCLABLE paper. Radio 90.9 FM: A mix of classical music and NPR information programs, including local news. (Also heard at 106.5 in Danville and with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See pages 4-5. 101.1 FM and 90.9 FM HD2: Locally produced music programs and classical music from C24. (101.1 The month of July means we’ve moved into a is available in the Champaign-Urbana area.) See page 6. new fiscal year here at Illinois Public Media. 580 AM: News and information, NPR, BBC, news, agriculture, talk shows. (Also heard on 90.9 FM HD3 First and foremost, I want to give a big thank with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See page 7. you to everyone who renewed or increased your gift to Illinois Public Media over the last Television 12 months. You continue to show your love and WILL-HD All your favorite PBS and local programming, in high support for what we do time and again. I am definition when available. -

Spring 2008 Volume 109, Number 1 WISCONSIN

Spring 2008 Volume 109, Number 1 WISCONSIN Reluctant Star 18 The UW scientist who first brought stem cells into the scientific spotlight — a discovery that sparked a volatile debate of political and medical ethics — doesn’t seek fame for himself. So when you are the go-to guy for everybody who wants access to James Thomson, a man who’d much rather be in the lab than in the media’s glare, you learn to say no more often than you’d like. By Terry Devitt ’78, MA’85 Seriously Funny 22 Some thought that Ben Karlin ’93 was walking away from success when he left his job as executive producer for TV’s The Daily 18 Show and The Colbert Report. But, as he explains in this conversation with On Wisconsin, he was simply charting a comedic path that includes a new book and his own production company. By Jenny Price ’96 Can of Worms 28 Graduate students have more to worry about than grades — there’s also research, funding, and, as the students working in one lab discovered, their mentor’s ethics. While PhD candidate Amy Hubert x’08 aims to overcome scandal and put the finishing touches on her degree, the UW struggles to protect the students who will create the future of science. 22 By John Allen INSIDE Campus on $5 a Day LETTERS 4 34 If a bill featuring Abe’s face is burning a hole in your pocket, SIFTING & WINNOWING 9 you’d be amazed to learn what it can buy on campus. Don some comfort- DISPATCHES 10 able shoes and discover what you can eat, see, and do at bargain prices. -

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report General Committees

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT GENERAL COMMITTEES Public Bill Committee RATING (CORONAVIRUS) AND DIRECTORS DISQUALIFICATION (DISSOLVED COMPANIES) BILL First Sitting Tuesday 6 July 2021 (Morning) CONTENTS Programme motion agreed to. Written evidence (Reporting to the House) motion agreed to. Motion to sit in private agreed to. Examination of witnesses. Adjourned till this day at Two o’clock. PBC (Bill 11) 2021 - 2022 No proofs can be supplied. Corrections that Members suggest for the final version of the report should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Saturday 10 July 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1 Public Bill Committee6 JULY 2021 Rating (Coronavirus) and Directors 2 Disqualification (Dissolved Companies) The Committee consisted of the following Members: Chairs: DAVID MUNDELL,†CHRISTINA REES † Baker, Duncan (North Norfolk) (Con) † Scully, Paul (Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State † Baynes, Simon (Clwyd South) (Con) for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy) † Grant, Peter (Glenrothes) (SNP) † Smith, Jeff (Manchester, Withington) (Lab) † Hall, Luke (Minister for Regional Growth and Local Tomlinson, Michael (Lord Commissioner of Her Government) Majesty’s Treasury) † Hunt, Jane (Loughborough) (Con) † Webb, Suzanne (Stourbridge) (Con) † Jenkinson, -

Lumbricus Rubellus)

An investigation of genetic heterogeneity in a biological sentinel species (Lumbricus rubellus) Robert Kevin Donnelly A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy This research programme was carried out in collaboration with Cardiff University September 2011 Summary Studies have indicated the existence of several possible sources of genetic heterogeneity within the sentinel species Lumbricus rubellus that could compromise its suitability for ecotoxicological assessment. The species appears to consist of two genetically divergent cryptic lineages and has been demonstrated to display genetic adaptation towards contaminants within some populations. In order to investigate the cryptic lineages of L rubellus further a combined morphological and DNA barcoding approach was undertaken, with both the mitochondria! COI gene being sequenced and external morphological characters being assessed. Combined barcoding and morphological analysis confirmed the existence of the previously described genetic lineages of L. rubellus and highlighted a potential lineage-specific morphological trait. The effectiveness of this trait in field identification of the two lineages was tested in a blind trial. This indicated that the trait may be particularly effective in successfully identifying the individuals of one of these lineages. The two cryptic lineages were also analysed in a second study featuring cross-amplifying microsatellite loci. Both the sequencing and fragment analysis of these microsatellite loci strongly supported the existence of a high degree of reproductive isolation between the two lineages. Finally microsatellite markers were applied to test the hypothesis of genetic adaptation within L. rubellus populations located along an aerially-deposited nickel contamination gradient. -

Copyright and Collective Authorship

Copyright and Collective Authorship As technology makes it easier for people to work together, large-scale collaboration is becoming increasingly prevalent. In this context, the question of how to determine authorship – and hence ownership – of copyright in collaborative works is an important question to which cur- rent copyright law fails to provide a coherent or consistent answer. In Copyright and Collective Authorship, Daniela Simone engages with the problem of how to determine the authorship of highly collaborative works. Employing insights from the ways in which collaborators under- stand and regulate issues of authorship, the book argues that a recalibra- tion of copyright law is necessary, proposing an inclusive and contextual approach to joint authorship that is true to the legal concept of authorship but is also more aligned with creative reality. Dr. Daniela Simone is a Lecturer in Law at University College London, where she is also a Co-Director of the Institute of Brand and Innovation Law. Dr Simone holds BCL, MPhil and DPhil degrees from the University of Oxford. Prior to moving to the UK, she was awarded a BA/LLB (Hons I) degree from the University of Sydney, Australia, was admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales and worked as a lawyer for a global commercial law firm in Sydney. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Access paid by the UC Merced Library, on 02 May 2019 at 20:00:56, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108186070 Cambridge Intellectual Property and Information Law As its economic potential has rapidly expanded, intellectual property has become a subject of front-rank legal importance. -

Linking Phenotype to Genotype. Craig Anderson 2012

Mechanistic bases of metal tolerance: linking phenotype to genotype. Craig Anderson 2012 PhD Thesis Cardiff University School of Biological Sciences Abstract Ecotoxicology is currently undergoing a revolution as the result of new technological advances in molecular biology, capable of finely resolving metabolic mechanisms associated with exposure. These high-throughput analyses can detail the evolutionary and ecological implications of exposure in non-model organisms, such as the earthworm, Lumbricus rubellus. This terrestrial sentinel has been observed across former mine sites that are highly contaminated with arsenic and have been found to mitigate toxicity at soil concentrations that cause mortality in unadapted populations. This is indicative of the adaptive capacity of natural populations recently exposed to persistent and strong selection pressure. However, mechanisms surrounding adaptation to arsenic in L. rubellus have yet to be characterised, and so the effects of exposure are broadly reported with the aim of distinguishing resistance from phenotypic plasticity in natural populations. Unadapted earthworms were initially used to derive basal phenotypic variation associated with arsenic exposure. Variation in life-history parameters was observed among adult and juvenile L. rubellus, establishing relative sensitivity and population- level inferences. A systems biology approach was employed to describe molecular mechanisms associated with arsenic metabolism, encompassing transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses, underpinned by arsenic speciation. Insight into the genetic bases of arsenic resistance, which enable persistence of L. rubellus at highly contaminated sites, was sought. Recombinant inbred lineages derived from adapted populations, were cultivated and their phenotypes relative to arsenic exposure determined. Phylogeographic analyses were used to interrogate genetic variation among populations inhabiting former mine sites as well as proximal control sites. -

Filozofické Aspekty Technologií V Komediálním Sci-Fi Seriálu Červený Trpaslík

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Teorie interaktivních médií Dominik Zaplatílek Bakalářská diplomová práce Filozofické aspekty technologií v komediálním sci-fi seriálu Červený trpaslík Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Martin Flašar, Ph.D. 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracoval samostatně a použil jsem literárních a dalších pramenů a informací, které cituji a uvádím v seznamu použité literatury a zdrojů informací. V Brně dne ....................................... Dominik Zaplatílek Poděkování Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat panu PhDr. Martinu Flašarovi, Ph.D za odborné vedení této bakalářské práce a podnětné a cenné připomínky, které pomohly usměrnit tuto práci. Obsah Úvod ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Seriál Červený trpaslík ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Vyobrazené technologie ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Android Kryton ....................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1. Teologická námitka ........................................................................................................ 15 2.1.2. Argument z vědomí ....................................................................................................... 18 2.1.3. Argument z -

A Glossary of Northwest Acronyms and Terms

A Glossary of Northwest Acronyms and Terms A Mighty Fortress Is Our God - Christian hymn originally written in German by Martin Luther. The national anthem of the Northwest American Republic. ASU - Active Service Unit. The basic building block of the NVA paramilitary structure. Generally speaking, an active service unit was any team or affinity group of Northwest Volunteers engaged in armed struggle against the United States government. The largest active service units during the War of Independence were the Flying Columns (q.v.) that moved across the countryside in open insurrection. These could sometimes number as many as 75 or even 100 men. More usual was the urban team or crew ranging from four or five to no more than a dozen Volunteers. After a unit grew larger than seven or eight people, the logistics of movement and supply and also the risk of betrayal reached unacceptably high levels, and the cell would divide in two with each half going its separate way. Command and coordination between the units was often tenuous at best. The success and survival of an active service unit was often a matter of the old Viking adage: “Luck often enough will save a man. if his courage hold.” Aztlan - A semi-autonomous province of Mexico consisting of the old American states of southern and western Texas. Arizona. New Mexico. Utah, parts of Colorado, and southern California below a line roughly parallel with the Mountain Gate border post. BATF - Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms division of the United States Treasury Department. Used by the government in Washington D.