An Interim Report ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION of the EXTRAMURAL MONUMENTAL COMPLEX ('THE SOUTHERN CANABAE') at CAERLEON, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

Introducing Cadw INTRODUCING July 2019 Conwy Castle’S World Heritage Site Status Rightly Recognises It As a Masterpiece of Medieval Military Design

Introducing Cadw July 2019 INTRODUCING Conwy Castle’s World Heritage Site status rightly recognises it as a masterpiece of medieval military design. © Crown copyright (2019), Cadw, Welsh Government Cadw, Welsh Government Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed Parc Nantgarw Cardiff CF15 7QQ Tel: 03000 256000 Email: [email protected] Website: http://gov.wales/cadw Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown copyright 2019 WG37616 Digital ISBN 978-1-83876-520-0 Print ISBN 978-1-83876-522-4 Cover photograph: Caernarfon Castle and town show how the historic environment is all around us. In this small area you can see numerous scheduled monuments, listed buildings and a conservation area all within a World Heritage Site. © Crown copyright (2019), Cadw, Welsh Government 02 Introducing Cadw Introducing Cadw Dolwyddelan Castle, built by the Welsh prince, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, in the heart of Snowdonia. © Crown copyright (2019), Cadw, Welsh Government Cadw is the Welsh Government’s historic environment service. We are working for an accessible and well-protected historic environment for Wales. We do this by: • helping to care for our historic environment for the benefit of people today and in the future • promoting the development of the skills that are needed to look after our historic environment properly • helping people to cherish and enjoy our historic environment • making our historic environment work for our economic well-being • working with partners to achieve our common goals together. Cadw is part of the Welsh Government’s Culture, Sport and Tourism Department and is answerable to the Deputy Minister, Lord Dafydd Elis-Thomas AM. -

Print Finishers

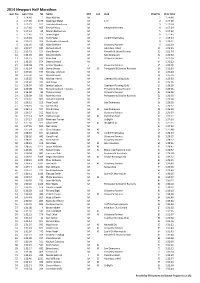

2014 Newport Half Marathon Gun Pos Gun Time No Name M/F Cat Club Chip Pos Chip Time 1 1:14:46 1 Ryan McFlyn M 1 1:14:46 2 1:17:09 1175 Matthew Welsh M 1 Tri 2 1:17:08 3 1:17:15 910 Leighton Rawlinson M 3 1:17:14 4 1:17:30 865 Emrys Penny M Newport Harriers 4 1:17:29 5 1:17:43 68 Maciej Bialogonski M 5 1:17:42 6 1:17:46 316 James Elgar M 6 1:17:45 7 1:19:35 372 Tom Foster M Cardiff Triathletes 7 1:19:34 8 1:20:33 926 Christopher Rennick M 8 1:20:31 9 1:21:10 425 Mike Griffiths M Lliswerry Runners 9 1:21:09 10 1:21:27 680 Richard Lloyd M Aberdare VAAC 10 1:21:25 11 1:21:52 117 Gary Brown M Penarth & Dinas Runners 11 1:21:50 12 1:22:03 801 Doug Nicholls M San Domenico 12 1:22:02 13 1:22:21 625 Alun King M Lliswerry Runners 13 1:22:18 14 1:22:25 574 Dean Johnson M 14 1:22:22 15 1:22:38 772 Emma Wookey F Lliswerry Runners 15 1:22:36 16 1:22:54 256 Steve Davies M 50 Pontypool & District Runners 16 1:22:52 17 1:25:26 575 Nicholas Johnson M 17 1:25:24 18 1:25:50 597 Richard Jones M 18 1:25:39 19 1:25:55 458 Michael Harris M Caerleon Running Club 19 1:25:53 20 1:26:02 163 Jack Casey M 20 1:25:56 21 1:26:07 162 James Casburn M Caerleon Running Club 22 1:26:05 22 1:26:08 541 Richard Jackson-Hookins M Penarth & Dinas Runners 23 1:26:06 23 1:26:09 82 Thomas Bland M Lliswerry Runners 24 1:26:06 24 1:26:09 531 Mark Hurford M Pontypool & District Runners 21 1:26:03 25 1:26:10 803 Daniel Oakenfull M 25 1:26:08 26 1:26:12 215 Pete Croall M San Domenico 26 1:26:10 27 1:26:15 57 Jon Belcher M 27 1:26:12 28 1:26:43 107 Phil Bristow M 50 San Domenico 28 1:26:40 -

Coridor-Yr-M4-O-Amgylch-Casnewydd

PROSIECT CORIDOR YR M4 O AMGYLCH CASNEWYDD THE M4 CORRIDOR AROUND NEWPORT PROJECT Malpas Llandifog/ Twneli Caerllion/ Caerleon Llandevaud B Brynglas/ 4 A 2 3 NCN 4 4 Newidiadau Arfaethedig i 6 9 6 Brynglas 44 7 Drefniant Mynediad/ A N tunnels C Proposed Access Changes 48 N Pontymister A 4 (! M4 C25/ J25 6 0m M4 C24/ J24 M4 C26/ J26 2 p h 4 h (! (! p 0 Llanfarthin/ Sir Fynwy/ / 0m 4 u A th 6 70 M4 Llanmartin Monmouthshire ar m Pr sb d ph Ex ese Gorsaf y Ty-Du/ do ifie isti nn ild ss h ng ol i Rogerstone A la p M4 'w A i'w ec 0m to ild Station ol R 7 Sain Silian/ be do nn be Re sba Saint-y-brid/ e to St. Julians cla rth res 4 ss u/ St Brides P M 6 Underwood ifi 9 ed 4 ng 5 Ardal Gadwraeth B M ti 4 Netherwent 4 is 5 x B Llanfihangel Rogiet/ 9 E 7 Tanbont 1 23 Llanfihangel Rogiet B4 'St Brides Road' Tanbont Conservation Area t/ Underbridge en Gwasanaethau 'Rockfield Lane' w ow Gorsaf Casnewydd/ Trosbont -G st Underbridge as p Traffordd/ I G he Newport Station C 4 'Knollbury Lane' o N Motorway T Overbridge N C nol/ C N Services M4 C23/ sen N Cyngor Dinas Casnewydd M48 Pre 4 Llanwern J23/ M48 48 Wilcrick sting M 45 Exi B42 Newport City Council Darperir troedffordd/llwybr beiciau ar hyd Newport Road/ M4 C27/ J27 M4 C23A/ J23A Llanfihangel Casnewydd/ Footpath/ Cycleway Provided Along Newport Road (! Gorsaf Pheilffordd Cyffordd Twnnel Hafren/ A (! 468 Ty-Du/ Parcio a Theithio Arfaethedig Trosbont Rogiet/ Severn Tunnel Junction Railway Station Newport B4245 Grorsaf Llanwern/ Trefesgob/ 'Newport Road' Rogiet Rogerstone 4 Proposed Llanwern Overbridge -

Setting of Historic Assets in Wales

Setting of Historic Assets in Wales May 2017 MANAGING 01 Setting of Historic Assets in Wales Statement of Purpose Setting of Historic Assets in Wales explains what setting is, how it contributes to the significance of a historic asset and why it is important. Setting of Historic Assets in Wales also outlines the principles used to assess the potential impact of development or land management proposals within the settings of World Heritage Sites, ancient monuments (scheduled and unscheduled), listed buildings, registered historic parks and gardens, and conservation areas. These principles, however, are equally applicable to all individual historic assets, irrespective of their designation. The guidance is not intended to cover the setting of the historic environment at a landscape scale. This is considered by separate guidance.1 This best-practice guidance is aimed at developers, owners, occupiers and agents, who should use it to inform management plans and proposals for change which may have an impact on the significance of a historic asset and its setting. It should also help them to take account of Cadw’s Conservation Principles for the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment in Wales (Conservation Principles) to achieve high- quality sensitive change.2 Decision-making authorities and their advisers should also use this guidance alongside Planning Policy Wales,3 Technical Advice Note 24: The Historic Environment,4 Conservation Principles and other best-practice guidance to inform local policies and when considering individual applications for planning permission and listed building, scheduled monument and conservation area consent, including pre-application discussions. Welsh Government Historic Environment Service (Cadw) Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed Parc Nantgarw Cardiff CF15 7QQ Telephone: 03000 256000 Email: [email protected] First published by Cadw in 2017 Digital ISBN 978 1 4734 8700 0 © Crown Copyright 2017, Welsh Government, Cadw, except where specified. -

All Wales Comic Verse Competition

All Wales Comic Verse Competition Entry Form Name: Title of Poem: Poem No. Address: Tel: Mobile: Email: Please tick below:- 1/ I have read, and agree to abide by, all Rules, Terms and Conditions of The Competition. [ ] 2/ I state that all poetry submitted is my own work. [ ] Signed: Date: …/…/… Please send the appropriate entry fee (£3.00 per poem, maximum of three poems) to:- 27 Hawthorn Gardens, Caerleon. NP18 1NX Cheques should be made payable to:- Celf Caerleon Arts festival Rules 1/ Writers are permitted to enter a maximum of three previously unpublished poems in English (at £3.00 per entry for administrative costs). 2/ Each poem should not be more than 30 lines in length. 3/ The author’s name should not be written on the poem/s, but only on the accompanying entry documentation. 4/ The closing date for entries is shown on the Caerleon Festival website, Comic Verse page. Entries received after this date will not be deemed eligible. No refund will be given for late entry. 5/ Entries sent without the correct entry documentation will not be deemed eligible. No refund will be given for incorrect submission. 6/ All entries shall be judged blind on humorous content and poetic merit. Ten poems will be selected from the entries, and their authors asked to attend and read publically the chosen verse live at the competition in Caerleon on the date shown on the Festival website. The live competition shall be judged on humorous content, performance and poetic merit. 7/ All authors will be asked to bring along a second unpublished poem in English to read in the event of a tie. -

Cunetio Roman Town, Mildenhall Marlborough, Wiltshire

Wessex Archaeology Cunetio Roman Town, Mildenhall Marlborough, Wiltshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 71509 July 2011 CUNETIO ROMAN TOWN, MILDENHALL, MARLBOROUGH, WILTSHIRE Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared for: Videotext Communications Ltd 11 St Andrew’s Crescent CARDIFF CF10 3DB by Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 71509.01 Path: \\Projectserver\WESSEX\PROJECTS\71509\Post Ex\Report\71509/TT Cunetio Report (ed LNM) July 2011 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2011 all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Cunetio Roman Town, Mildenhall, Marlborough, Wiltshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results DISCLAIMER THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT WAS DESIGNED AS AN INTEGRAL PART OF A REPORT TO AN INDIVIDUAL CLIENT AND WAS PREPARED SOLELY FOR THE BENEFIT OF THAT CLIENT. THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT DOES NOT NECESSARILY STAND ON ITS OWN AND IS NOT INTENDED TO NOR SHOULD IT BE RELIED UPON BY ANY THIRD PARTY. TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMITTED BY LAW WESSEX ARCHAEOLOGY WILL NOT BE LIABLE BY REASON OF BREACH OF CONTRACT NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGE (WHETHER DIRECT INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL) OCCASIONED TO ANY PERSON ACTING OR OMITTING TO ACT OR REFRAINING FROM ACTING IN RELIANCE UPON THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT ARISING FROM OR CONNECTED WITH ANY ERROR OR OMISSION IN THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THE REPORT. LOSS OR DAMAGE AS REFERRED TO ABOVE SHALL BE DEEMED TO INCLUDE, BUT IS NOT LIMITED TO, ANY LOSS OF PROFITS OR ANTICIPATED PROFITS DAMAGE TO REPUTATION OR GOODWILL LOSS OF BUSINESS OR ANTICIPATED BUSINESS DAMAGES COSTS EXPENSES INCURRED OR PAYABLE TO ANY THIRD PARTY (IN ALL CASES WHETHER DIRECT INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL) OR ANY OTHER DIRECT INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL LOSS OR DAMAGE QUALITY ASSURANCE SITE CODE 71509 ACCESSION CODE CLIENT CODE PLANNING APPLICATION REF. -

Flooding and Historic Buildings in Wales

Flooding and Historic Buildings in Wales July 2019 TECHNICAL Statement of Purpose Flooding and Historic Buildings in Wales provides For information on specific historic buildings and guidance on ways to establish flood risk and prepare guidance on whether remedial treatments and repairs for possible flooding by installing protection measures. require consent, you should consult the conservation It also recommends actions to be taken during and officer in the local planning authority. after a flood to minimise damage and risks. Sources of further information and practical help are Aimed principally at home owners, owners of small listed at the end of the document. businesses and others involved with managing historic buildings, Flooding and Historic Buildings in Wales explains how to approach the protection of traditional buildings and avoid inappropriate modern repairs in the event of flood damage. Acknowledgement Cadw is grateful to Historic England for permission the express written permission of both Historic to base the text of this best-practice guidance on England and Cadw. All rights reserved. Historic Flooding and Historic Buildings, published in 2015. England does not accept liability for loss or damage arising from the use of the information contained The original material is ©Historic England 2015. in this work. www.historicengland.org.uk/images- Any reproduction of the original Work requires books/publications/flooding-and-historic-buildings- Historic England’s prior written permission and any 2ednrev reproduction of this adaptation of that Work requires Cadw Welsh Government Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed Parc Nantgarw Cardiff CF15 7QQ Telephone: 03000 256000 Email: [email protected] Website: https://cadw.gov.wales/ First published by Cadw in 2019 Digital ISBN 978-1-83876-805-8 © Crown Copyright, Welsh Government, Cadw, except where specified. -

Allt Yr Yn Profile 2019 Population

2019 Community Well-being Profile Allt-yr-yn Population Final July 2019 v1.0 Table of Contents Table of Contents Population ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Population make up .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Population Density .............................................................................................................................................10 Population Changes ............................................................................................................................................11 Supporting Information ......................................................................................................................................13 Gaps ....................................................................................................................................................................15 Allt-yr-yn Community Well-being Profile – Population Page 1 Allt-yr-yn Population Population Overview Population 8,966 % of the Newport Population 5.92% Population Density 2,338.5 Ethnic Minority Population 13.9% (population per km2) Area (km2) 3.83 Lower Super Output Areas 6 % of -

Allt-Yr-Yn Profile

2017 Community Well-being Profile Allt-yr-yn Final May 2017 Table of Contents Table of Contents Preface ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Section 1: Allt-yr-yn Community Overview .............................................................................................................. 5 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 The population of the community ........................................................................................................................ 7 What is the make-up of the population? ............................................................................................................. 9 What will the population be in the future? ........................................................................................................12 Section 2: Economic well-being ..............................................................................................................................13 What is the economic well-being of our community? .......................................................................................13 Job Seeker’s Allowance ......................................................................................................................................17 What do we know about the economic well-being of -

Understanding Traditional (Pre-1919) and Historic Buildings for Construction and Built Environment Courses Contents ¬

Understanding Traditional (pre-1919) and Historic Buildings for Construction and Built Environment Courses TEACHING RESOURCE TEACHING Who should use this teaching resource? Princes Foundation Building Crafts Trainee Miriam Johnson gaining hands-on experience working with thatch. The programme involves working on a range of historic buildings using traditional materials and techniques. For more on the Building Crafts programme visit www.princes-foundation.org/education/building-craft- programme-heritage-skills-nvq-level-3. © Princes Foundation This teaching resource will help anyone who is It has been written as an introduction to traditional or will be teaching an understanding of traditional (pre-1919) and historic buildings and presents key (pre-1919) buildings as part of construction and terminology and approaches. built environment courses and qualifications. It will be useful for learners who will work on and It is designed for teachers, construction lecturers plan to work on a range of existing buildings. and assessors at schools, further education colleges and independent training providers. Further information and links to useful resources on careers in the heritage construction sector are provided in the Find out more section, as well as options for further study and training. Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown copyright 2019 WG37560 Digital ISBN 978-1-83876-519-4 This teaching resource has been written by Cadw and Historic England. © Crown copyright (2019), Cadw, Welsh Government and © Historic England. Version 1, July 2019. Cover photograph: Conservation works in 2018 to repair the chimneys at Castell Coch, a grade I listed building and scheduled monument in south Wales. -

Ministers Priorities for the Historic Environment

Priorities for the Historic Environment of Wales Lord Elis-Thomas AM, Minister for Culture, Tourism and Sport September 2018 AMBITION Our industrial monuments tell how Wales helped to shape the modern world. Here, in the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape World Heritage Site, Big Pit, part of the National Museum of Wales, stands only a short distance away from Cadw’s Blaenavon Ironworks. © Crown copyright (2018), Visit Wales Cadw, Welsh Government Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed Parc Nantgarw Cardiff CF15 7QQ Tel: 03000 256000 Email: [email protected] Website: http://cadw.gov.wales Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown copyright 2018 WG35767 Digital ISBN 978-1-78937-950-1 Print ISBN 978-1-78937-952-5 Cover photograph: Criccieth Castle and town looking across Cardigan Bay towards Snowdonia. © Crown copyright (2018), Visit Wales 02 Priorities for the Historic Environment in Wales Introduction Wales as a nation has emerged from a shared cultural inheritance over thousands of years. However, at the end of the twentieth century our nation came of age with the devolution settlement and once again it now has law-making powers. It was fitting that one of the first pieces of legislation that was passed by the National Assembly for Wales was for the better protection of the historic environment. As a consequence of the Historic Environment (Wales) Act 2016, many observers, both inside and outside Wales, have hailed us for now having the most progressive legislation for the protection and management of the historic Lord Elis-Thomas at Castell y Bere, environment anywhere in the United Kingdom.