Britannia: from Conquest to Province, AD 43–C.84

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Criminal Trials in the Julio-Claudian Era

Women in Criminal Trials in the Julio-Claudian Era by Tracy Lynn Deline B.A., University of Saskatchewan, 1994 M.A., University of Saskatchewan, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Classics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) September 2009 © Tracy Lynn Deline, 2009 Abstract This study focuses on the intersection of three general areas: elite Roman women, criminal law, and Julio-Claudian politics. Chapter one provides background material on the literary and legal source material used in this study and considers the cases of Augustus’ daughter and granddaughter as a backdrop to the legal and political thinking that follows. The remainder of the dissertation is divided according to women’s roles in criminal trials. Chapter two, encompassing the largest body of evidence, addresses the role of women as defendants, and this chapter is split into three thematic parts that concentrate on charges of adultery, treason, and other crimes. A recurring question is whether the defendants were indicted for reasons specific to them or the indictments were meant to injure their male family members politically. Analysis of these cases reveals that most of the accused women suffered harm without the damage being shared by their male family members. Chapter three considers that a handful of powerful women also filled the role of prosecutor, a role technically denied to them under the law. Resourceful and powerful imperial women like Messalina and Agrippina found ways to use criminal accusations to remove political enemies. Chapter four investigates women in the role of witnesses in criminal trials. -

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

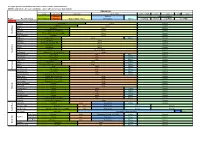

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Caratacus Errata

Caratacus Module Errata & Clarifications February, 2008 Components Counters There are 60 counters provided with the module. Corrections and additions to the counters include: •• The Briton MI should be BI instead •• Togudumnus counter is missing. Use any TC from Caesar/Gaul substituting the following ratings: Order/Line Range is 4/7; Initiative is 4; Charisma is 2 •• Cnaeus Sentius (commander of the Batavians) should have the following ratings: Command Range is 3; Initiative is 3; Line Command is 1; Charisma is 1; Strategy is 6. He is not a Cavalry commander, but the leader of the Batavians. The Briton army contains the following units: •• 2 Overall Commanders (Caratacus and Togodumnus) •• 3 Subordinate commanders (Taximagulus, Cingetorix, and Segovax chiefs of the Trinovantes, Atrebates and Cantii, respectively) •• 30 LI with 30 CH •• 20 BI (the MI counters) •• 4 LC Not all of the counters included in the module are used in the battles. There are 8 extra Briton BI (masquerading as MI, to be sure). Please use only 20 of these (you could always use the extras to alter play balance. Better more than too few). There is an extra Briton LI and CH, although including them is not exactly going to alter the game to any great extent. The extra CH counters are used for the extra Brit LI, which always used chariots to get around town. Since the original publication of the module, GMT has added 40 counters. This set includes: •• 20 Briton BI to replace the 20 Briton MI from the original counter set •• Togodumnus •• Cn. Sentius (ignore the Cav designation on the counter) •• 4 Batavian MI and 2 Batavian LI •• 12 Testudo/Harass & Disperse Markers Applicable Errata for Caesar: Conquest of Gaul Ignore this section when using the Caesar: Conquest of Gaul 2nd Edition rules. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Now the War Is Over

Pollard, T. and Banks, I. (2010) Now the wars are over: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields. International Journal of Historical Archaeology,14 (3). pp. 414-441. ISSN 1092-7697. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/45069/ Deposited on: 17 November 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Now the Wars are Over: the past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Tony Pollard and Iain Banks1 Suggested running head: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Centre for Battlefield Archaeology University of Glasgow The Gregory Building Lilybank Gardens Glasgow G12 8QQ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)141 330 5541 Fax: +44 (0)141 330 3863 Email: [email protected] 1 Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland 1 Abstract Battlefield archaeology has provided a new way of appreciating historic battlefields. This paper provides a summary of the long history of warfare and conflict in Scotland which has given rise to a large number of battlefield sites. Recent moves to highlight the archaeological importance of these sites, in the form of Historic Scotland’s Battlefields Inventory are discussed, along with some of the problems associated with the preservation and management of these important cultural sites. 2 Keywords Battlefields; Conflict Archaeology; Management 3 Introduction Battlefield archaeology is a relatively recent development within the field of historical archaeology, which, in the UK at least, has itself not long been established within the archaeological mainstream. Within the present context it is noteworthy that Scotland has played an important role in this process, with the first international conference devoted to battlefield archaeology taking place at the University of Glasgow in 2000 (Freeman and Pollard, 2001). -

MONS GRAUPIUS Alternative Names: None Late 83 Or 84 CE Date Published: July 2016 Date of Last Update to Report: N/A

Inventory of Historic Battlefields Research report This battle was researched and assessed against the criteria for inclusion on the Inventory of Historic Battlefields set out in Historic Environment Scotland Policy Statement June 2016 https://www.historicenvironment.scot/advice-and- support/planning-and-guidance/legislation-and-guidance/historic-environment- scotland-policy-statement/. The results of this research are presented in this report. The site does not meet the criteria at the current time as outlined below (see reason for exclusion). MONS GRAUPIUS Alternative Names: None Late 83 or 84 CE Date published: July 2016 Date of last update to report: N/a Overview The Battle of Mons Graupius is the best documented engagement between the Roman forces, stationed in southern Britannia, and the Caledonian tribes of the northern part of the island. It marked the culmination of multiple years of campaigning by the Roman governor of the province, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, against the “barbarian” tribes and he inflicted a resounding defeat on the confederacy of Caledonians arrayed against him. Much of what is known about the battle is contained within the Agricola, written in 97-98 CE by Agricola’s son in law, the Roman historian Tacitus. This is a heavily biased and only partially surviving account which amounts to a veneration of Agricola. There are no indigenous accounts of the battle and no archaeological evidence has been confirmed as connected to the conflict. Although the site has drawn attention from academics since antiquarian times, the precise date, location and the vast majority of details of the engagement remain unconfirmed. Reason for exclusion There is no certainty about the location of the battle, and there are also significant questions about the accuracy of the accounts describing it. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

Summary of Motions California State Retirees (Csr) Board of Directors Meeting

SUMMARY OF MOTIONS CALIFORNIA STATE RETIREES (CSR) BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING Holiday Inn, Sacramento February 22, 2018 7. Approval of October 26, 2017 Board Meeting Minutes CSR 1/18/1 MOTION: Oliveira, second by Hueg - that the CSR Board of Directors approve the minutes of the October 26, 2017 meeting as printed. CARRIED. 11. Program Reports - HQ CSR 2/18/1 MOTION: Fountain, second by Hueg – that the CSR Board of Directors buy the three promotion items, hats, totes and lapel pins, in bulk and send out numbers to chapters. CARRIED. 12. Political Action Committee CSR 3/18/1 MOTION: Oliveira, second by Fountain – that the CSR Board of Directors endorse incumbents Controller Betty Yee and Secretary of State Alex Padilla for reelection. CARRIED. CSR 4/18/1 MOTION: Umemoto, second by Jimenez – that the CSR Board of Directors endorse Treasurer Fiona Ma. CARRIED. CSR 5/18/1 MOTION: Jimenez, second by Oliveira – that the CSR Board of Directors endorse the following Assembly incumbents seeking reelection: AD 01 Brian Dahle (R-Bieber), AD 02 Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg), AD 03 James Gallagher (R-Nicolaus), AD 04 Cecilia Aguiar-Curry (D-Napa), AD 05 Frank Bigelow (R-O’Neals), AD 06 Kevin Kiley (R-El Dorado Hills), AD 07 Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento), AD 08 Ken Cooley (D-Rancho Cordova), AD 09 Jim Cooper (D-Elk Grove), AD 10 Marc Levine (D-San Rafael), AD 11 Jim Frazier (D-Oakley), AD 12 Heath Flora (R-Modesto), AD 13 Susan Eggman (D-Stockton), AD 14 Tim Grayson (D-Concord), AD 16 Catharine Baker (D-Dublin), AD 17 David Chiu (D-San Francisco), AD 18 Rob Bonta (D-Alameda), AD 19 Phil Ting (D-San Francisco), AD 20 Bill Quirk (D- Hayward), AD 21 Adam Gray (D-Merced). -

The Blood Crows Kindle

THE BLOOD CROWS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Simon Scarrow | 512 pages | 08 May 2014 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755353828 | English | London, United Kingdom The Blood Crows PDF Book But unable to find him, unable to stop the murders, Anderson is forced to follow the only lead he has - Skelpie Fairbairn. Details if other :. I've always had scarrow as the most enjoyable Roman series, and a return to Britain for macro and Cato takes them back to more familiar ground. Read more Once again it's been two years since I last read one in this series so at times it took me a minute or two to recall "recent" event in the lives of some of the characters. Once again I found the characters likeable with the dynamics between them being convincing. It could have literally been written in pages instead of Historical novel. All 4. Come on, there are other options! May 14, Bill Ward rated it it was amazing. One of the solid books from the Eagle series. This book picks up six years later — following adventures across the entire Roman Empire — with the only difference being the reversal in roles, Now, Cato is the higher in rank — a Prefect, whilst Macro still remains a Centurion. The ending was quite good, but still so boring. Oct 19, Pat rated it did not like it. Brothers in Blood Eagles of the Empire This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged. That's okay. Talk about being gutted!!! They were loads of fun with a well meaning young man in bad circumstances, a wise cracking older, wise side kick, and lots of twists and turns - oh, and plenty of good old fashioned Roman on Barbarian Briton, German, Dacian, Palestinian, Syrian, etc battles. -

Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: H Interdisciplinary Volume 15 Issue 8 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate Reasons for the Invasion of Britain by Claudius By Tomoyo Takahashi University of California, United States Abstract- In 43 AD, the fourth emperor of Imperial Rome, Tiberius Claudius Drusus, organized his military and invaded Britain. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the legitimate reasons for The Invasion of Britain led by Claudius. Before the invasion, his had an unfortunate life. He was physically distorted, so no one gave him an official position. However, one day, something unimaginable happened. He found himself selected by the Praetorian Guard to be the new emperor of Roma. Many scholars generally agree Claudius was eager to overcome his physical disabilities and low expectations to secure his position as new Emperor in Rome by military success in Britain. Although his personal motivation was understandable, it was not sufficient enough for Imperial Rome to legitimize the invasion of Britain. It is important to separate personal reasons and official reasons. Keywords: (1) roman, (2) britain, (3) claudius, (4) roman emperor, (5) colonies, (6) slavery, (7) colchester, (8) veterans, (9) legitimacy. GJHSS-H Classification: FOR Code: 180114 HumanRightsSocialWelfareandGreekPhilosophyLegitimateReasonsfortheInvasionofBritainbyClaudius Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2015. Tomoyo Takahashi. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

CN May 37-44.Indd

In focus CHRIS RUDD Same king in two places? Or two kings with the same name? ID the same Celtic king rule in East Anglia and the West Midlands? If so, when did he go west and why? Or were there two kings with the same name, ruling at roughly the same time? If so, why did they inscribe their names in the same way? Who copied whom? And who was Arviragus? Was he the same person as Antedrigus? Was he the second Dson of Cunobelinus? Or was the chronicler Geoff rey of Monmouth fi bbing? I can’t answer all these questions. But I can tell you a bit about the controversial coin which is causing them to be asked again. In 1994/95 Terry Howard, a professional musician, went On the obverse there is a branched symbol sprouting from metal detecting and found an exceedingly rare gold coin near a ringed pellet, which I interpret as a druidic “Tree of Life” South Cerney, Gloucestershire, not far from where he also symbol growing out of the sun. Turn it upside down and it found an enamelled “horse brass” of regal quality. He reported looks like a stylised skull and rib cage—a symbol of mortality. his fi nds to the Corinium Museum in Cirencester. Terry’s coin, On the reverse we see a stylised and somewhat disjointed which is coming up for auction in May this year, is a gold stater horse with three tails, not unlike the Uffi ngton White Horse that was struck in the late Iron Age by Anted, a king of the carved out of a chalk hillside over 2,500 years ago (only around Dobunni tribe in the West Midlands, some time around AD 18 miles from where this coin was found).