"You Can't Have It on a Plate Forever": the English Class System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BWTB Nov. 13Th Dukes 2016

1 Playlist Nov. 13th 2016 LIVE! From DUKES in Malibu 9AM / OPEN Three hours non stop uninterrupted Music from JPG&R…as we broadcast LIVE from DUKES in Malibu…. John Lennon – Steel and Glass - Walls And Bridges ‘74 Much like “How Do You Sleep” three years earlier, this is another blistering Lennon track that sets its sights on Allen Klein (who had contributed lyrics to “How Do You Sleep” those few years before). The Beatles - Revolution 1 - The Beatles 2 The first song recorded during the sessions for the “White Album.” At the time of its recording, this slower version was the only version of John Lennon’s “Revolution,” and it carried that titled without a “1” or a “9” in the title. Recording began on May 30, 1968, and 18 takes were recorded. On the final take, the first with a lead vocal, the song continued past the 4 1/2 minute mark and went onto an extended jam. It would end at 10:17 with John shouting to the others and to the control room “OK, I’ve had enough!” The final six minutes were pure chaos with discordant instrumental jamming, plenty of feedback, percussive clicks (which are heard in the song’s introduction as well), and John repeatedly screaming “alright” and moaning along with his girlfriend, Yoko Ono. Ono also spoke random streams of consciousness on the track such as “if you become naked.” This bizarre six-minute section was clipped off the version of what would become “Revolution 1” to form the basis of “Revolution 9.” Yoko’s “naked” line appears in the released version of “Revolution 9” at 7:53. -

Proof That John Lennon Faked His Death

return to updates Proof that John Lennon Faked his Death Mark Staycer or John Lennon? by Miles Mathis This has been a theory from the very beginning, as most people know, but all the proof I have seen up to now isn't completely convincing. What we normally see is a lot of speculation about the alleged shooting in December of 1980. Many discrepancies have indeed been found, but I will not repeat them (except for a couple in my endnotes). I find more recent photographic evidence to be far easier and quicker to compile—and more convincing at a glance, as it were—so that is what I will show you here. All this evidence is based on research I did myself. I am not repeating the work of anyone else and I take full responsibility for everything here. If it appeals to you, great. If not, feel free to dismiss it. That is completely up to you, and if you don't agree, fine. When I say “proof” in my title, I mean it is proof enough for me. I no longer have a reasonable doubt. This paper wouldn't have been possible if John had stayed well hidden, but as it turns out he still likes to play in public. Being a bit of an actor, and always being confident is his ability to manipulate the public, John decided to just do what he wanted to do, covering it just enough to fool most people. This he has done, but he hasn't fooled me. The biggest clues come from a little indie film from Toronto about Lennon called Let Him Be,* released in 2009, with clips still up on youtube as of 2014. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

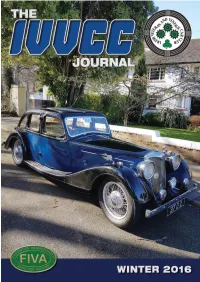

Ivvcc Winter 2016 Web

Classic Car insurance that comes with a well-polished service Your Classic Car insurance policy includes: Free agreed value1 Salvage retention rights1 Up to 15% off for membership of a recognised owners club1 Irish & European accident breakdown recovery, including Homestart assistance worth over €100 Up to €100,000 legal protection in the event of an accident which is not your fault European travel cover up to 45 days1 Dedicated Irish call centre2 1800Accept nothing less, call 930 for a Classic Car insurance801 quote Classic Bike Multi-Bike Custom Bike Performance Bike Scooter & Moped carolenash.ie / insidebikes @insidebikes 1 Subject to Terms & Conditions, call for details. 2 Whilst most calls are handled in Ireland sometimes your call may be answered by our UK call centre. Carole Nash Insurance consultants Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, firm reference number 307243. Carole Nash is a trading style of Carole Nash Insurance Consultants Ltd, registered in England and Wales No 2600841. In Ireland, it is subject to the Central Bank of Ireland’s conduct of business rules. EDITORIAL Dear Fellow Motoring Enthusiasts, elcome to the Winter edition of the IVVCC Journal. Once again I am an issue behind. I am sorry for the delay but am unable to get articles in which Wprevents publication of the Journal. If you can provide articles or pictures (or both), I would be grateful and be able to catch up! In this issue, Camillus Ryan shares his rare Riley with us. This is a time warp car, largely original and from a seldom seen era. -

Dlr Libraries Adult Book Club Sets to Request Please Email: [email protected]

dlr Libraries Adult book club sets To request please email: [email protected] Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi: Purple hibiscus: 20 copies The limits of fifteen-year-old Kambili's world are defined by the high walls of her family estate and the dictates of her fanatically religious father. Her life is regulated by schedules: prayer, sleep, study, prayer. When Nigeria is shaken by a military coup, Kambili’s father, involved mysteriously in the political crisis, sends her to live with her aunt. In this house, noisy and full of laughter, she discovers life and love – and a terrible, bruising secret deep within her family. 2003, 307 pages Alexander, Aimee: The accidental life of Greg Millar: 10 copies Lucy Arigho’s first encounter with Greg Millar is far from promising, but she soon realises he possesses a charm that is impossible to resist. Just eight whirlwind weeks after their first meeting, level-headed career girl Lucy is seriously considering his pleas to marry him and asking herself if she could really be stepmother material. But before Lucy can make a final decision about becoming part of Greg’s world, events plunge her right into it. On holiday in the South of France, things start to unravel. Her future stepchildren won’t accept her, the interfering nanny resents her, and they’re stuck in a heat wave that won’t let up. And then there’s Greg. His behaviour becomes increasingly bizarre and Lucy begins to wonder whether his larger-than-life personality hides something darker—and whether she knows him at all. -

The 5Th Beatle Outline

THE FIFTH Outline for a Documentary Written by David Johnston “The Beatles are the most famous rock group that has ever existed or ever will exist. They are, in fact, the second-most-famous four- human collective within any context whatsoever (the four Gospel writers are No. 1; Notre Dame’s 1924 “Four Horsemen” backfield rank a distant third). Moreover, the Beatles are the only band whose population is central to their iconography: John, Paul, George and Ringo shall always be the Fab Four. And because that number is so important, pop historians have spent decades trying to decide who deserves classification as Beatle No. 5.” Chuck Klosterman, obituary of Quarryman and “Tenth Beatle” Eric Griffiths in The New York Times Magazine, December 25th, 2005 Many have aspired to it, some have claimed it for themselves, a rare few have had it bestowed upon them, but to date no one person has established an uncontested claim to the title of Fifth Beatle. The Fifth will take up and examine the debate and trace the growth of this unique pop cultural phenomenon. A handful of the Beatles’ fellow travellers hold a legitimate claim to Fifth Beatle status – early members such as bass player/fashion maven Stuart Sutcliffe and drummer Pete Best, manager and Beatlemania impresario Brian Epstein, producer/arranger George Martin and Billy Preston, the only musician to share a writing credit with the band (on “Get Back”) and who was asked by John Lennon to join the band shortly before its breakup. But it doesn’t stop there. Yoko Ono, Linda Eastman, tour managers Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans, Jimmy Nichol (the drummer who replaced Ringo for several weeks on tour in 1964), deejay Murray the K (who coined the term Fifth Beatle), and crazed mentor Tony Sheridan are among the usual suspects. -

The Summer of Love: Hippie Culture and the Beatles in 1967

TCNJ JOURNAL OF STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP VOLUME XVI APRIL, 2014 THE SUMMER OF LOVE: HIPPIE CULTURE AND THE BEATLES IN 1967 Author: Kathryn Begaja Faculty Sponsor: David Venturo, Department of English ABSTRACT Though the hippie ideology had been brewing under the radar in San Francisco for many years, in June of 1967, the necessary catalyst appeared to advance the hippie movement to nationwide prominence, encouraging thousands of American youths to reject mainstream ideology. That catalyst, the record- topping Beatles’ album Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, conveyed the simplest principles of the counterculture: LSD, love, and rejection of the unhip establishment. Entering into “the zone of maximal contact,” the Beatles’ music inspired thousands to make a hippie pilgrimage to Haight-Ashbury.1 Known to its residents as “the Haight,” this San Francisco district adapted to the influx of hippies with the creation of an alternative social order, including functional counterinstitutions to serve the needs of the hippie community. Again, the Beatles’ enter into a dialogue with the revolutionary hippie lifestyle by developing their own counterinstitution: Apple Corps. The Beatles’ interaction with the hippie counterculture allowed the utopian visions of both groups to reach peak levels of intensity during the Summer of Love. INTRODUCTION For a few, brief months in 1967, the United States was shocked by a counterculture influence that was able to permeate the mainstream, influencing popular music and demanding media attention. Known as the Summer of Love, this era marked the peak of hippie influence on America. The hippie movement of the nineteen-sixties evolved from the Beatnik counterculture of the previous decade. -

Proof That John Lennon Faked His Death

return to updates Proof that John Lennon Faked his Death Mark Staycer or John Lennon? by Miles Mathis This has been a theory from the very beginning, as most people know, but all the proof I have seen up to now isn't completely convincing. What we normally see is a lot of speculation about the alleged shooting in December of 1980. Many discrepancies have indeed been found, but I will not repeat them (except for a couple in my endnotes). I find more recent photographic evidence to be far easier and quicker to compile—and more convincing at a glance, as it were—so that is what I will show you here. All this evidence is based on research I did myself. I am not repeating the work of anyone else and I take full responsibility for everything here. If it appeals to you, great. If not, feel free to dismiss it. That is completely up to you, and if you don't agree, fine. When I say “proof” in my title, I mean it is proof enough for me. I no longer have a reasonable doubt. This paper wouldn't have been possible if John had stayed well hidden, but as it turns out he still likes to play in public. Being a bit of an actor, and always being confident is his ability to manipulate the public, John decided to just do what he wanted to do, covering it just enough to fool most people. This he has done, but he hasn't fooled me. The biggest clues come from a little indie film from Toronto about Lennon called Let Him Be,* released in 2009, with clips still up on youtube as of 2014. -

WALK the REVOLUTION! Drink As Well As Live Music

elcome to Sixties London: a place and time celebrated 02 V&A ‘Revolutions’ Shop, It also hosted veteran star bands including The Mothers of 11 Saville Theatre, 135 Shaftesbury Avenue in the latest major exhibition at the Victoria and 56a Carnaby Street Invention, Pink Floyd and The Who (who referred to the club on In 1965, Beatles manager Brian Epstein leased this former CHELSEA Albert Museum You Say You Want a Revolution: The V&A shop has taken up their album ‘The Who Sell Out’). The Beatles threw a party for theatre as a venue for plays as well as rock and roll shows. The 01 Royal Court, Sloane Square WRecords and Rebels 1966–1970. Throughout the late sixties, Soho, residence at 56a Carnaby Street, The Monkees here during their 1967 visit to England. Jimi Hendrix Experience opened a set here on 4th June 1967 The Royal Court Theatre regularly came into conflict with the Chelsea, Kensington and Ladbroke Grove were hubs of creativity creating a temporary retail space with a cover of ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, from Lord Chamberlain’s Office (official censor of the London stage) and revolutions in music, fashion, food, politics and sex. themed around the exhibition 07 Regent Street Polytechnic, 309 Regent Street The Beatles album, released just three days earlier. A stunned throughout the 1960s. To evade censorship, the Royal Court In Soho, a thriving centre of the popular music industry You Say You Want a Revolution? Founding members of the revolutionary rock group Pink Floyd: Paul McCartney and George Harrison looked on in the audience. -

KLOS June 22Nd 2014

1 1 2 PLAYLIST JUNE 22ND 2014* *So…If ya missed it. On yesterday’s’ show played a Beatles song that nobody’s ever played before on the radio. It’s the full version of the song coming out of Ringo’s radio in the film A Hard Day’s Night. We would like to thank Dave Morrell for bringing it in and for being such a Fab guest. Dave’s new book as called Horse – Doggin` and you should buy it now. http://www.amazon.com/Horse-Doggin-The-Morrell-Archives- Volume/dp/149734607X 2 3 9AM The Beatles - A Day In The Life - Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocals: John and Paul Work began on January 19, 1967, for what is quite possibly the finest Lennon- McCartney collaboration of their songwriting career. On this evening, following some rehearsal, Lennon rolled tentatively through four takes, drawing a road map for the other Beatles and George Martin to follow. Lennon on vocals and Jumbo acoustic guitar, McCartney on piano, Harrison on maracas and Starr on congas. Sections were incomplete and to hold their space Mal Evans stood by a microphone and counted from one to 24, marking the time. To cue the end of the middle eight overdub section an alarm clock was sounded. There was no Paul McCartney vocal yet, merely instruments at this point where his contribution would be placed. On January 20, Paul added his section, which he would re-recorded on February 3. Lennon told Beatles biographer Hunter Davies that the first verse was inspired by a story in the January 17, 1967, edition of the Daily Mail about the car accident that killed Guinness heir Tara Browne. -

Blog Globs "None Are More Hopelessly Enslaved Than Those Who Falsely Believe They Are Free" -Goethe

Blog Globs "None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free" -Goethe. If you like this blog, please add it to your favourites, and share it with others. Corporate controlled media is 90% misleading. The Canadian government is one of the best in the world, but only when they're honest. For some real news and radio shows, I recommend you check this out: http://www.conspiracyculture.com/ For questions about God, try here: http://www.gotquestions.org/ SUNDAY, JULY 18, 2010 What's Wrong with the Beatles? Alot. Occult Symbols on Beatles Album Covers I used to be a huge Beatles fan. Let's face it, they were super-talented and charismatic. They were always presented as being sweet, innocent, harmless, and fun. Yet over the years, I've noticed more and more negative influences they've had on society. The Beatles' debut. They're already "looking down on us from above". The balconies are a hidden 6/6/6. The group's name looks like it's at the bottom of an abyss. Their handlers probably designed this one. Even this early album cover has occult imagery. They have the "One Eye of Horus" showing, which is epidemic on cd covers today, 46 years later. They are also half in the shadows (in masonry and taoism, the balance of dark and light=the balance of good and evil)). Their faces are "illuminated" by the sun. On the US version, Meet the Beatles, John's dark eye was obscured more. Once again, their handlers probably designed this one, not the boys. -

Yoko Ono and John Lennon's 1969 Year Of

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MASS MEDIA IS THE MESSAGE: YOKO ONO AND JOHN LENNON’S 1969 YEAR OF PEACE Martha Ann Bari, PhD., 2007 Directed By: Assistant Professor Renée Ater, Department of Art History and Archaeology In 1969, against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, multimedia artist Yoko Ono and rock star John Lennon instigated a series of idiosyncratic artistic events designed to spread a universal message of peace. What all these events had in common was the couple’s keen desire to act as catalysts for change and their willingness to exploit their own celebrity to do so. They had just survived a scandalous year in London in a fishbowl of publicity where the popular press savaged Ono and Lennon’s love affair and resulting separate divorces. Dealing with the insatiable media had become part of their everyday lives. Why not use this pervasive attention to publicize their own cause and carry their message of peace throughout the world? This simple premise launched a private peace campaign whose artistic message has achieved cult status in our popular culture. This dissertation examines how Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s 1969 Year of Peace unfolded, how the media covered it at the time, and how people remember it today. By considering the couple's art events within the context of the 1960s and then following the path of certain images as they wend their way to the present, Ono and Lennon’s art acts as a core sample of sixties culture and its legacy. My study situates this artwork against the backdrop of Lennon’s megawatt rock star celebrity, within the spirit of Fluxus (of which Ono was a founding member), and in the context of the anti-war movement of the time.