Paralanguage and the Beatles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surround Sound Auteurs and the Fragmenting of Genre

Alan Williams: Surround Sound Auteurs and the Fragmenting of Genre Proceedings of the 12th Art of Record Production Conference Mono: Stereo: Multi Williams, A. (2019). Surround Sound Auteurs and the Fragmenting of Genre. In J.-O. Gullö (Ed.), Proceedings of the 12th Art of Record Production Conference Mono: Stereo: Multi (pp. 319-328). Stockholm: Royal College of Music (KMH) & Art of Record Production. Alan Williams: Surround Sound Auteurs and the Fragmenting of Genre Abstract Multi-channel sonic experience is derived from a myriad of technological processes, shaped by market forces, configured by creative decision makers and translated through audience taste preferences. From the failed launch of quadrophonic sound in the 1970s, through the currently limited, yet sustained niche market for 5.1 music releases, a select number of mix engineers and producers established paradigms for defining expanded sound stages. Whe- reas stereophonic mix practices in popular music became ever more codified during the 1970s, the relative paucity of multi-channel releases has preserved the individual sonic fingerprint of mixers working in surround sound. More- over, market forces have constricted their work to musical genres that appeal to the audiophile community that supports the format. This study examines the work of Elliot Scheiner, Bob Clearmountain, Giles Martin, and Steven Wilson to not only analyze the sonic signatures of their mixes, but to address how their conceptions of the soundstage become associated with specific genres, and serve to establish micro-genres of their own. I conclude by ar- guing that auteurs such as Steven Wilson have amassed an audience for their mixes, with a catalog that crosses genre boundaries, establishing a mode of listening that in itself represents an emergent genre – surround rock. -

Badass Band 47- MAKAR

Badass Band 47- MAKAR (hps://badassbandsblog.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/makar.jpg) Jonesing for a dynamic guy/girl duo to add to your music repertoire? Look no further music lovers. Not only is this duo talented musically, they are after this music fiend’s own heart considering that the members are writers aside from their songwriting, Andrea is even a published poet. They are quite out of the ordinary as you will find in listening to their tunes, and their range is broad which offers ear solace to any kind of music lover. Badass Band 47 is New York’s MAKAR. MAKAR is another band that found me, and once their tunes hit my ears, I had a hard time deciding which of them I liked best. It was almost as if I went into super ADD mode, I was clicking on all their tracks trying to decide which I liked best right off the bat and they were all so different I couldn’t sele on one. I ended up forcing myself to just download them all and listen to them in order from start to finish. So, that being said, let’s start by talking about the vocals. Andrea’s vocals I can really only describe as light and refreshing. They have power, but not in the traditional sense, in the sense that they are so soft and singsongy that you just can help but listen. For me this is especially exemplified on songs like ‘I Wanna Know What I Don’t Know’ or ‘Belong Here’ As for Mark, his voice is deep but also keeps the more light, singsongy quality that Andrea’s has. -

Electric Light Orchestra – Secret

Electric Light Orchestra – Secret Messages [Double- Vinyl-Reissue] (34:06, 37:57; 2 LP,Sony Music/Legacy, 1983/2018) Immer wieder stolpert man als Musikliebhaber über skurrile Geschichten in Zusammenhang mit Veröffentlichungen berühmter Alben. Auch das im Juni 1983 erschienene Werk „Secret Messages“ vom „Electric Light Orchestra“ hat eine ungewöhnliche Entstehungsgeschichte. Jeff Lynne hatte im Vorfeld der Produktion eine besonders produktive Kompositionsphase, sodass während der Sessions zu „Secret Messages“ nicht weniger als 18 Songs aufgenommen wurden. Nichts lag näher als aus „Secret Messages“ ein Doppelalbum zu machen. Dass ELO in Sachen Doppelalben ein gutes Standing hatten, hatte bereits „Out Of The Blue“ eindrucksvoll bewiesen. Aber nix da – Der Boss von CBS legte wegen zu hoher Produktionskosten sein Veto ein, und so wurde aus „Secret Messages“ nur eine einfache LP/CD mit 10 bzw. 11 Stücken. Zwar wurden etliche gestrichene Stücke als Single-B- Seiten doch noch veröffentlicht, doch „Secret Messages“ war ein Kastrat und vielleicht auch deshalb deutlich weniger erfolgreich als sein Vorläufer. Dazu kam ein recht typischer Achtziger-PVC-Klang, der hie und da auch nicht dem Gusto der Fangemeinde entsprach. Zum Schutz Ihrer persönlichen Daten ist die Verbindung zu YouTube blockiert worden. Klicken Sie auf Video laden, um die Blockierung zu YouTube aufzuheben. Durch das Laden des Videos akzeptieren Sie die Datenschutzbestimmungen von YouTube. Mehr Informationen zum Datenschutz von YouTube finden Sie hier Google – Datenschutzerklärung & Nutzungsbedingungen. YouTube Videos zukünftig nicht mehr blockieren. Video laden 25 Jahre später erscheint das Album nun erstmals fast so wie ursprünglich geplant als Doppel-Album. „Fast“ deshalb, weil der Titel „Beatles Forever“ weiterhin ausgespart bleibt. -

Par Richard Baillargeon

par Richard Baillargeon Pour la 3 e fois à Québec, la 2 e fois dans mon cas, et pour la première fois dans une prestation à l'intérieur, Paul McCartney nous offrait un généreux périple à travers son imposan- te production d'un demi-siècle en musique-chanson populaire. L'événement lançait sa nouvelle tournée Freshen Up , le lundi soir 17 septembre 2018, dix jours seulement après le lancement, dûment célébré par les fans de Beatles Québec, de son album Egypt Station . Pour ceux qui avaient opté pour la version VIP de l'événement, la fête avait commencé en milieu d'après-midi. Mais c'est plutôt en tant que fan 'simple citoyen' que je m'approchai du Centre Vidéotron vers 18h 30, billet de la section 209 en main. Déjà, des files de spectateurs se formaient et déambulaient lentement en direction de l'angle sud-est de l'amphithéâtre, là où se trouve l'accès principal. Sur la Place Jean-Béliveau, il était impossible de ne pas remarquer le bus à impériale (double-decker bus) aux couleurs de l'exposition Ici Londres du Musée de la civilisation. Au second étage du véhicule, le groupe Les Respectables créait l'ambiance avec leur mélange de mélodies beatlesques, de standards pop et de quelques-uns de leurs propres succès. Je décidai cependant de ne pas trop m'attarder, ayant déjà perçu des mouvements de foule du côté des portes. L'entrée se fit aisément, la quantité des postes de contrôle facilitant l'exercice. Ce fut une excellente idée d'entrer sur-le-champ car le flot des spectateurs allait dès lors se faire constant jusqu'au début du spectacle qui eut lieu vers 20h 10. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Sweat: the Exodus from Physical and Mental Enslavement to Emotional and Spiritual Liberation

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation Aqueelah Roberson University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Roberson, Aqueelah, "Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3319. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3319 SWEAT: THE EXODUS FROM PHYSICAL AND MENTAL ENSLAVEMENT TO EMOTIONAL AND SPIRITUAL LIBERATION by AQUEELAH KHALILAH ROBERSON B.A., North Carolina Central University, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2007 © 2007 Aqueelah Khalilah Roberson ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to showcase the importance of God-inspired Theatre and to manifest the transformative effects of living in accordance to the Word of God. In order to share my vision for theatre such as this, I will examine the biblical elements in Zora Neale Hurston’s short story Sweat (1926). I will write a stage adaptation of the story, while placing emphasis on the biblical lessons that can be used for God-inspired Theatre. -

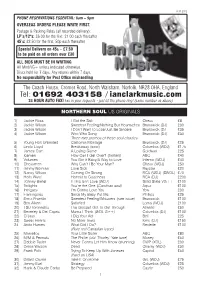

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Was Original Whom He Liked, Though He's Not Too Keen on Originally As Nobody Ever Asked Me to Play Live

HARRY NILSSON r.,I3 ej ictor "We thought it had a sense of humour. I don't know... things that the studio has to offer which you can't do in I guess I'm just bitter about it. I think that sense of g a live situation. I did some TV shows in America a long humour is the single most lacking thing in popular time ago -the Johnny Carson show, the Mike Douglas music. It's also the single most lacking quality in the show -with just me and a piano. people that present popular music to the public. It hurts, "I was once advised to do live shows and appear on TV. because that's what rock'n'roll is all about -fun. I agreed to the TV. 'Everybody's Talkin" had just come out and "'Acting lilce a man on a fuzzy tree. .'It's humour. How serious can you it was a hit, so I went on this TV show. I didn't have a suit to wear so I get about'your baby, my baby'?Lots of musicians take it too seriously and borrowed my manager's suit, which didn't fit. As soon as it was over it's dull and boring, and that's what's killing pop music. I like humour and I realised I was making a mistake and stopped doing it. My reputation I like songs that have humour. That's why I'm arguing with RCA. is now unscathed. "They don't get the joke aboutGod's Greatest Hits.I asked them whether "I've talked about it with the band that I use on the albums but I don't they'd have turned downJesus Christ Superstarfor the same reason. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 77 JANUARY 28TH, 2019 Welcome to Copper #77! I hope you had a better view of the much-hyped lunar-eclipse than I did---the combination of clouds and sleep made it a non-event for me. Full moon or no, we're all Bozos on this bus---in the front seat is Larry Schenbeck, who brings us music to counterbalance the blah weather; Dan Schwartz brings us Burritos for lunch; Richard Murison brings us a non-Python Life of Brian; Jay Jay French chats with Giles Martin about the remastered White Album; Roy Hall tells us about an interesting day; Anne E. Johnson looks at lesser-known cuts from Steely Dan's long career; Christian James Hand deconstructs the timeless "Piano Man"; Woody Woodward is back with a piece on seminal blues guitarist Blind Blake; and I consider comfort music, and continue with a Vintage Whine look at Fairchild. Our reviewer friend Vade Forrester brings us his list of guidelines for reviewers. Industry News will return when there's something to write about other than Sears. Copper#77 wraps up with a look at the unthinkable from Charles Rodrigues, and an extraordinary Parting Shot taken in London by new contributor Rich Isaacs. Enjoy, and we’ll see you soon! Cheers, Leebs. Stay Warm TOO MUCH TCHAIKOVSKY Written by Lawrence Schenbeck It’s cold, it’s gray, it’s wet. Time for comfort food: Dvořák and German lieder and tuneful chamber music. No atonal scratching and heaving for a while! No earnest searches after our deepest, darkest emotions. What we need—musically, mind you—is something akin to a Canadian sitcom. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964