A Historical Case Study of the Ohio Fellows: a Co-Curricular Program and Its Influence on Success Level of Review: EXEMPT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 President's Report | the Rise of OHIO's Third

K100 60 40 40 100 OHIO UNIVERSITY AT A GLANCE The place where you live, learn, and grow is important. Students come to OHIO for an excellent education. Here they become scholars, leaders, researchers, and engaged citizens. They study abroad, volunteer, and form friendships that last a lifetime. History Established in 1804, Ohio University is the oldest public institution of higher learning in the state of Ohio and the first in the Northwest Territory. Admission to Ohio University is granted to the best-qualified applicants as determined by a selective admission policy. University Profile • A four-year public institution located in Athens, Ohio • 17,500+ undergraduate students on the Athens Campus • More than 250 academic programs • More than 1,000 full-time faculty members (Athens Campus) • 18:1 student faculty ratio • 33-student average class size • 43 residence halls housing more than 8,000 students • 450+ registered student organizations • 34 fraternities and sororities • 16 NCAA Division I teams in the Mid-American Conference • Average freshman total gift aid: $5,640 Freshman Class Profile Fall 2016 middle 50 percent range • High school class rank: 68% • Composite ACT: 24 • Combined SAT (Math + Critical Reading): 1103 • Average GPA: 3.48 (4.0 Scale) Recognition Ohio University has been cited for academic quality and value by such publications as U.S. News and World Report, America’s 100 Best College Buys, Princeton Review’s Best Colleges, and Peterson’s Guide to Competitive Colleges. The John Templeton Foundation has recognized Ohio University as one of the top character-building institutions in the country. Additionally, OHIO is listed among the top producers in the country of Fulbright Award-winning students by The Chronicle of Higher Education. -

Download This PDF File

The Ohio Journal of Volume 116 No. 1 April Program ANSCIENCE INTERNATIONAL MULTIDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL Abstracts The Ohio Journal of SCIENCE Listing Services ISSN 0030-0950 The Ohio Journal of Sciencearticles are listed or abstracted in several sources including: EDITORIAL POLICY AcadSci Abstracts Bibliography of Agriculture General Biological Abstracts The Ohio Journal of Scienceconsiders original contributions from members and non-members of the Academy in all fields of science, Chemical Abstracts technology, engineering, mathematics and education. Submission Current Advances in Ecological Sciences of a manuscript is understood to mean that the work is original and Current Contents (Agriculture, Biology & unpublished, and is not being considered for publication elsewhere. Environmental Sciences) All manuscripts considered for publication will be peer-reviewed. Deep Sea Research and Oceanography Abstracts Any opinions expressed by reviewers are their own, and do not Environment Abstracts represent the views of The Ohio Academy of Science or The Ohio Journal of Science. Environmental Information Center Forest Products Abstracts Forestry Abstracts Page Charges Geo Abstracts Publication in The Ohio Journal of Science requires authors to assist GEOBASE in meeting publication expenses. These costs will be assessed at $50 per page for nonmembers. Members of the Academy do not Geology Abstracts pay page charges to publish in The Ohio Journal of Science. In GeoRef multi-authored papers, the first author must be a member of the Google Scholar Academy at the time of publication to be eligible for the reduced Helminthological Abstracts member rate. Papers that exceed 12 printed pages may be charged Horticulture Abstracts full production costs. Knowledge Bank (The Ohio State University Libraries) Nuclear Science Abstracts Submission Review of Plant Pathology Electronic submission only. -

2015 Ohiodance Fall Festival and Conference

2015 OhioDance Fall Festival and Conference Dance Matters: Moving Forward #ohiodancefest October 23-25, 2015 Special Guest Artist Kyle Abraham Co-sponsored by Ohio University, School of Dance, Film, and Theater, Division of Dance in Athens, Ohio Kyle Abraham Photo by Celeste Sloman Photo Courtesy of Kyle Abraham/AbrahamIn.Motion Photo Courtesy of Ohio University Division of Dance www.ohiodance.org BFA in Choreography and Performance BA in Dance Dance Minors in Choreography DANCE and Performance, Dance History and Theory, and Somatic Studies For more info contact us at: Ohio University Dance Division 137 Putnam Hall • Athens, OH 45701 Office: (740) 593-1826 Fax: (740) 593-0749 Email: [email protected] www.ohio.edu/finearts/dance Photo Credit: Larry Coleman 2 www.ohiodance.org Dance Matters: Moving Forward OhioDance, the leading state-wide organization supporting diverse dance practices, will hold its fall festival October 23-25, 2015. This event is co-hosted by Ohio University, School of Dance, Film, and Theater, Division of Dance in Athens, Ohio. The theme and title of the conference, Dance Matters: Moving Forward, encompasses the idea that no matter what future changes may occur, dance and the arts will always forge ahead creatively, kinesthetically, and intellectually. Special events include Guest Artist Kyle Abraham will offer a master class and lecture. Abraham.In.Motion company members will provide a lecture demonstration. Over the three day weekend there will be a dance performance, a variety of master classes, dance film showings, a regional roundtable centered around the OhioDance Virtual Dance Collection, discussion on social media law and Ohio University dance division faculty will provide information Kyle Abraham about the dance program at OU for PreProfessional dancers as well as an audition by OU faculty for high school seniors. -

Ohio University Undergraduate Catalog 2005-2006

Ohio University The fees, programs, and requirements contained in this catalog are effective with Undergraduate the 2005 fall quarter. They are necessarily subject to change at the discretion Catalog 2005-2006 of Ohio University. It is the student’s responsibility to know and follow current requirements and procedures at the departmental, College, and University levels. Ohio University is an af fir ma tive Produced by the Office Ohio University (USPS 405-380), Volume action institution. of University Publications CII, Number 2, July 2005. Published Editor: Brian W. Stemen, M.A., ‘98 by Ohio University, University Terrace, Editorial Assistant: Erin L. Stookey, B.S.J., ‘05 Athens, Ohio 45701-2979 in March, Cover Design: Katie E. Ingersoll, B.F.A., ’06 July, August, September, and October. Periodicals Postage Paid at Athens, Copyright 2005 Ohio. Ohio University Communications and Marketing 0136–46M 2 Extended Community Ohio University Mission State ment Ohio University serves an extended community. The public service mission Ohio University is a public uni ver si ty providing a broad range of ed u- of the University, expressed in such ca tion al programs and services. As an academic community, Ohio activities as public broadcasting and University holds the intellectual and personal growth of the in di vid u al to continuing education programs, reflects be a central purpose. Its programs are designed to broaden perspectives, the re spon si bil i ty of the University to enrich awareness, deepen un der stand ing, establish disciplined habits serve the ongoing ed uca tion al needs of thought, prepare for mean ing ful careers and, thus, to help develop of the region. -

New Faculty Reference Guide

2021-2022 New Faculty Reference Guide Ohio University 1 | P a g e Table of Contents About Ohio University ..........................................................................................................................................3 University Founding ...........................................................................................................................................3 Ohio University Today .......................................................................................................................................4 Mission and Vision ..............................................................................................................................................6 Students.................................................................................................................................................................6 Faculty and Staff ..................................................................................................................................................7 Teaching ................................................................................................................................................................8 Scholarship, Research, and Creative Activity ..................................................................................................8 Academic Governance ...........................................................................................................................................9 Faculty Senate ......................................................................................................................................................9 -

President's Report New Frontiers

2011 PRESIDENT’S REPORT New FroNtiers TogeTher, Braving a new FronTier every year at ohio University (ohio) is a new frontier where aspirations become achievements Each fall, the academic year begins with the First-Year Student Convocation at the Convocation Center. Commencement ceremonies also take place at “The Convo,” providing a symbolic beginning and ending to the student experience at OHIO. 2011 PRESIDENT’S REPORT ConqUering new FronTiers is an OHIO TradiTion From health care research that may help people around the globe to supporting innovations and initiatives that spur economic development in our region, OHIO continues to expand the frontiers of the possible. Since our founding in 1804, we have been working to fulfill our mission of advancing knowledge on the frontiers of discovery while serving as a beacon of learning and opportunity. Some notable achievements from the past year include: • Ohio University’s Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine was awarded a record-breaking $105 million gift (see opposite page) that will help us make a difference in lives across the region. • OHIO students have continued building a tradition of earning the nation’s most competitive academic honors. Our Fulbright Award tally ranks Ohio University among such excellent institutions as Duke and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). • A group of our students, faculty, and staff assisted tsunami relief efforts in Japan. • OHIO was named one of the nation’s most military-friendly academic institutions in recognition of our efforts to serve students who are veterans. • Alumni, students, faculty, staff, and friends watched on national television as the OHIO Bobcats won their first football bowl game in our 208-year history. -

DEBORAH THORNE, Ph.D

DEBORAH THORNE, Ph.D. Address: Department of Sociology and Anthropology Email: [email protected] Phinney Hall 314 Cell phone: 740-407-8094 University of Idaho Moscow, Idaho ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2016-Present Associate Professor Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Idaho 2009-2015 Associate Professor Department of Sociology and Anthropology Ohio University 2002-2008 Assistant Professor Department of Sociology and Anthropology Ohio University 2001-2002 Post-doctoral Fellow and Project Director Consumer Bankruptcy Project Harvard University EDUCATION Ph.D. Sociology, Washington State University, 2001 Dissertation: “Personal Bankruptcy through the Eyes of the Stigmatized: Insight into Issues of Shame, Gender, and Marital Discord” M.A. Sociology, Washington State University, 1996 B.A. Sociology, Washington State University, 1994 WSU Honors Program, summa cum laude Minor: Women’s Studies HONORS 2019 University of Idaho, Excellence in General Education Teaching Award, “Social and Behavioral Ways of Knowing” nominee 2018 Carnegie Fellowship University of Idaho nominee 2016 Athens (Ohio) Best Professor, Athens News, Athens, Ohio 2014 University Professor, Ohio University (university-wide teaching award) 2009-12 Eric Wagner Endowed Teaching Professor, Ohio University 2010 Outstanding University College Student Advocate, Ohio University 2004 University Professor, Ohio University (university-wide teaching award) 2001-02 Post-doctoral Fellow and Project Director, Consumer Bankruptcy Project, Harvard University 1997 Joseph R. DeMartini -

Ohio University Undergraduate Catalog 2006–2008

Ohio University The fees, programs, and requirements contained in this catalog are effective with Undergraduate the 2006 fall quarter. They are necessarily subject to change at the discretion Catalog 2006–2008 of Ohio University. It is the student’s responsibility to know and follow current requirements and procedures at the departmental, College, and University levels. Ohio University is an affirmative Produced by the Office Ohio University (USPS 405-380), action institution. of University Communications and Marketing Volume CIII, Number 2, July 2006. Editor: Brian W. Stemen, M.A., ‘98 Published biennially by Ohio University, Editorial Assistant: Michelle Rushinsky, B.S.Ed., ‘06 University Terrace, Athens, Ohio 45701- Cover Design: Katie E. Ingersoll, B.F.A., ’06 2979 in March, July, August, September, Content Layout: Shelly D. Sheets and October. Periodicals Postage Paid at Athens, Ohio. Copyright 2006 Ohio University Communications and Marketing 0247–45M societal issues and needs through such Ohio University Mission Statement scholarship, research, and creative activ- ity. The scholarly and artistic activity of Ohio University is a public university providing a broad range of edu- the faculty enhances the teaching cational programs and services. As an academic community, Ohio function at all levels of the student University holds the intellectual and personal growth of the individual to experience. be a central purpose. Its programs are designed to broaden perspectives, Extended Community enrich awareness, deepen understanding, establish -

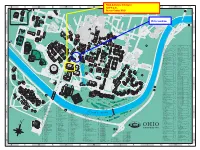

Athens Campus Map with Building Notes

Alphabetical Index Bldg. Grid Alphabetical Index...................Bldg. Grid 9 Factory Street...........................178 D-1 Lasher Hall.....................................21 G-3 35 Park Place .................................83 H-5 Lausche Heating Plant................108 D-3 63 South Green Drive. ................157 J-7 Library, Alden..................................5 H-4 Admissions, Office of......................9 G-3 Life Science Research Facility......149 F-3 Admissions, Visitor Parking..........56 H-4 Lin Hall ........................................201 C-7 AFSCME 1699...............................177 D-2 Lincoln Hall ...................................45 I-4 Airport, Directions to .................114 J-9 Lindley Hall ...................................17 G-4 Alden Library ..................................5 G-4 Mackinnon Hall.............................70 J-5 Alumni Center, Konneker.............60 H-5 Martzolff House..........................127 K-6 Alumni Gateway .........................176 H-3 McCracken Hall .............................42 J-3 Anderson Laboratory ...................77 G-4 McGuffey Hall .................................2 H-4 Aquatic Center..............................92 G-5 McKee House ................................59 I-4 Armbruster House ......................129 K-6 Morton Hall...................................78 I-5 Arts and Sciences, College Office...3 H-4 Nelson Commons ..........................72 J-6 Athena Cinema ...........................147 H-2 Oasis.......................................... -

Spectrum GREEN Volume 77 HIO UNIVERSITY^

Contents Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/spectrumgreen77ohio ENAGERIE ^ — — rf Spectrum GREEN Volume 77 HIO UNIVERSITY^ ^Aihens, bhio^5701 « Class Menagerie What is a menagerie? David DeNoma Dume yV. Fletcher " ebster's defines it as "a collection of live wild animals on exhibition, a place where animals are kept and trained. Some people might say this captures Ohio University and it's students perfectly . Sucey Kolhr Dujne W. Fletcher mixture/' a collection of unusual and unique things. This is O.U. A collection of events, of opportunities for learning, of methods of personal growth, and of course, a collection of individuals. Dvane W. Fletcher Djvid DeNomj We are a collection of classes — fresh- man, sophomore, junior and senior; black, white and in-between; rich, poor and "middle-class" — each with diverse moods, interests, likes and dislikes. We make up this collection, this mena- gerie, that is Ohio University. Rick E. Runion Campus Life ens — a city or contrasts Sandra Haggerty, a Athens is a transient city. The Farmer, owner of Parleys, and a macy," said professor, "People tend total population is 19,801 and 1978 O.U. graduate. "The students journalism 14,400 are college students, this are the bread and butter of this to get to know each other. Life in makes them an integral part of the town," Farmer added. Athens is a sense of community. I community. Athens is a city of contrasts. work here and live here, it's all According to Kenny Kerr, owner Tranquil hills surround busy rolled into one," she said. -

THE OHIO UNIVERSITY Cusipno

PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED JANUARY 27, 2017 NEW ISSUE – BOOK ENTRY ONLY Rating: Moody’s: Aa3 S&P: A+ (See “RATINGS” herein) In the opinion of Dinsmore & Shohl LLP, Bond Counsel, under existing law (i) assuming continuing compliance with certain covenants and the accuracy of certain representations, interest on the Series 2017A Bonds is excludible from gross income for federal income tax purposes and is not an item of tax preference for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals and corporations under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, and (ii) the Series 2017A Bonds, the transfer thereof, and the income therefrom, including any profit made on the sale thereof, are free from all Ohio state and local taxation, except the estate tax, the domestic insurance company tax, the dealers in intangibles tax, the tax levied on the basis of the total equity capital of financial institutions, and the net worth base of the corporate franchise tax. Interest on the Series 2017A Bonds may be subject to certain federal taxes imposed only on certain corporations, including the corporate alternative minimum tax on a portion of that interest. See “TAX EXEMPTION” herein. $148,295,000* THE OHIO UNIVERSITY (A State University of Ohio) General Receipts Bonds, Series 2017A Dated: Date of Initial Delivery Due: December 1, as shown below The $148,295,000* The Ohio University (A State University of Ohio) General Receipts Bonds, Series 2017A (the “Series 2017A Bonds”) are special obligations of The Ohio University (the “University”) pursuant to certain resolutions of the Board of Trustees of the University and a Trust Agreement dated as of May 1, 2001 (the “Master Trust Agreement”), as supplemented to date and as further supplemented by the Fourteenth Supplemental Trust Agreement dated as of March 1, 2017 (the “Fourteenth Supplemental Trust Agreement,” and together with the Master Trust Agreement as supplemented, the “Trust Agreement”), each between the University and U.S. -

Download 1 File

••'. , '.><r. Reflections OHIO UNIVERSITY -uC^K' REFLECTIONS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/athena88ohio The Athena Ohio University Athens, Ohio 45701 Volunne 88 Student Interests Student Life Issues Academics Sports Qreef^s Student Organizations Seniors 2 • TABLE OF CONTENTS The Athena yearbook reflects the attitude, atmosphere and soda climate of the university and the year. All aspects of student life, from classes to Uptown, are captured here, keeping the spirit of Ohio University 1 993 alive for decades. TABLE OF CONTENTS • 3 Reflections OHIO UNIVERSITY ERIC LOCSDON ABOVE LEFT: Rain and umbrellas on Morton ABOVE: Jim Melone and Mark E. Marquis share Hill show what the typical Athens weather is like, warm thoughts while strolling down E. Union LEFT: A lonely serenading guitarist celebrates Street, one of the few nice winter days. KEVIN KRECK 4 • OPENING RIGHT: Betsy Friedlander and her dog Marlee await her book-buying friend. BELOW: Kevin Jeray serves coffee to students as they diligently study for midterms al Another Fool's Cafe. ERIC LOCSDON ABOVE: Reflections of Biddle Hall on East Green. OPENING • 5 College Green RtTJL^ MONUMENT KEVIN KRECK ABOVE: A student rests in the shade of a tree on College Green. ERIC LOCSDON ABOVE: Seniors eat lunch and chat in the sun- shine of College Green, a pleasant alternative to uptown restaurants and dining halls. RIGHT: Three long-haired retrievers investigate crevices in the brick paths and walk their owner, junior Julia Lane. 6 • COLLEGE GREEN LEFT: Curious students use the monument as a vantage point tocatchaglimpse of Hillary Clinton.