Chapter 1 the Warrior Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bamcinématek Presents a Brand New 40Th Anniversary Restoration of Robert Clouse’S Enter the Dragon, Starring Bruce Lee, in a Week-Long Run, Aug 30—Sep 5

BAMcinématek presents a brand new 40th anniversary restoration of Robert Clouse’s Enter the Dragon, starring Bruce Lee, in a week-long run, Aug 30—Sep 5 Series sidebar features five wing chun classics including Sammo Hung’s The Prodigal Son, Chang Cheh’s Invincible Shaolin, and Bruce Lee’s The Way of the Dragon, beginning Aug 29 “Bruce Lee was the Fred Astaire of martial arts.”—Pauline Kael, The New Yorker The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Aug 7, 2013—From Friday, August 30 through Thursday, September 5, BAMcinématek presents a week-long run of Robert Clouse’s Enter the Dragon, screening in a new DCP restoration for its 40th anniversary. In conjunction with the release of Wong Kar-wai’s Ip Man biopic The Grandmaster, this series revels in the lightning-fast moves of the revered kung fu tradition known as wing chun, featuring a five-film sidebar of martial arts rarities. Passed on through generations of martial artists, wing chun was popularized by icons like Sammo Hung and Ip’s movie-star disciple Bruce Lee—and has become an action movie mainstay. The first Chinese martial arts movie to be produced by a major Hollywood studio, Clouse’s Enter the Dragon features Bruce Lee in his final role before his untimely death (just six days before the film’s theatrical release). Shaolin master Mr. Lee (Lee) is recruited to infiltrate the island of sinister crime lord Mr. Han by going undercover as a competitor in a kung fu tournament. -

A Brief Analysis of China's Contemporary Swordsmen Film

ISSN 1923-0176 [Print] Studies in Sociology of Science ISSN 1923-0184 [Online] Vol. 5, No. 4, 2014, pp. 140-143 www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/5991 www.cscanada.org A Brief Analysis of China’s Contemporary Swordsmen Film ZHU Taoran[a],* ; LIU Fan[b] [a]Postgraduate, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, effects and packaging have made today’s swordsmen China. films directed by the well-known directors enjoy more [b]Associate Professor, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, China. personalized and unique styles. The concept and type of *Corresponding author. “Swordsmen” begin to be deconstructed and restructured, and the swordsmen films directed in the modern times Received 24 August 2014; accepted 10 November 2014 give us a wide variety of possibilities and ways out. No Published online 26 November 2014 matter what way does the directors use to interpret the swordsmen film in their hearts, it injects passion and Abstract vitality to China’s swordsmen film. “Chivalry, Military force, and Emotion” are not the only symbols of the traditional swordsmen film, and heroes are not omnipotent and perfect persons any more. The current 1. TSUI HARK’S IMAGINARY Chinese swordsmen film could best showcase this point, and is undergoing criticism and deconstruction. We can SWORDSMEN FILM see that a large number of Chinese directors such as Tsui Tsui Hark is a director who advocates whimsy thoughts Hark, Peter Chan, Xu Haofeng , and Wong Kar-Wai began and ridiculous ideas. He is always engaged in studying to re-examine the aesthetics and culture of swordsmen new film technology, indulging in creating new images and film after the wave of “historic costume blockbuster” in new forms of film, and continuing to provide audiences the mainland China. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

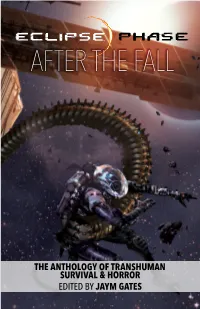

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

The Terena and the Caduveo of Southern Mato Grosso, Brazil

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION n INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOQY H PUBLICATION NO. 9 THE TERENA AND THE CADUVEO OF SOUTHERN MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL by KALERVO OBERG Digitalizado pelo Internet Archive. Disponível na Biblioteca Digital Curt Nimuendaju: http://biblio.etnolinguistica.org/oberg_1949_terena SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY PUBLICATION NO. 9 THE TERENA AND THE CADUVEO OF SOUTHERN MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL by KALERVO OBERG Prepared in Cooperation tiith the United States Department of State as a Project of the Interdrpartmental Committee on Scientific and Cultural Cooperation UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PIIINTING OFFICE-WASHINGTON:1949 For Bale by the Superintendent of Documenn, U.^S. Government Printing Office, WaohinBton 25, D. C. • Price 60 c LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Smithsonian Institution, Institute of Social Anthropology, WashinfftonSS, D. C, May 6, 1948 Sir: I have the honor to transmit herewith a manuscript entitled "The Terena and the Caduveo of Soutliern Mato Grosso, Brazil," by Kalervo Oberg, and to recommend that it be published as Publication Number 9 of the Institute of Social Anthropologj'. Very respectfully yours, George M. Foster, Director. Dr. Alexander Wetmore, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. CONTENTS PAGE The Terena—Continued page Introduction 1 The hfe cycle 38 The Terena 6 Birth (ipuhicoti-hiuki) 38 Terena economy in the Chaco 6 Puberty 39 Habitat 6 Marriage (koyendti) 39 Shelter 8 Burial 40 Clothing and ornaments 9 Collecting, hunting, and fishing 9 Modern changes 41 Agriculture 10 Religion 41 Domestic animals and birds 12 Rehgious beliefs 41 Manufactures 12 Shamanism 43 Raiding 13 Present-day religion 45 Property and inheritance 13 Secular entertainment 47 Organization of labor 13 Dances and games 47 Present-day economy of the Terena 13 General description 13 Football 51 Sources of income in a typical village. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Desajustamento: a Hermenêutica Do Fracasso E a Poética Do

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY E-ISSN 2237-2660 Misfitness: the hermeneutics of failure and the poetics of the clown – Heidegger and clowns Marcelo BeréI IUniversity of London – London, United Kingdom ABSTRACT – Misfitness: the hermeneutics of failure and the poetics of the clown – Heidegger and clowns – The article presents some Heideggerian ideas applied to the art of clowning. Four principles of practice of the clown’s art are analysed in the light of misfitness – a concept based on the clown’s ability not to fit into theatrical, cinematic and social conventions, thus creating a language of his own. In an ontological approach, this article seeks to examine what it means to be a clown-in-the-world. Following a Heideggerian principle, the clown is analysed here taking into account his artistic praxis; a clown is what a clown does: this is the basic principle of clown poetics. The conclusion proposes a look at the clown’s way of thinking – which is here called misfit logic – and shows the hermeneutics of failure, where the logic of success becomes questionable. Keywords: Heidegger. Clown. Phenomenology. Philosophy. Theatre. RÉSUMÉ – Misfitness (Inadaptation): l’herméneutique de l’échec et la poétique du clown – Heidegger et les clowns – L’article présente quelques idées heideggeriennes appliquées à l’art du clown. Quatre principes de pratique de l’art du clown sont analysés à la lumière de l’inadéquation – un concept basé sur la capacité du clown à ne pas s’inscrire dans les conventions théâtrales, cinématiques et sociales, créant ainsi son propre langage. Dans une approche ontologique, cet article cherche à examiner ce que signifie être un clown dans le monde. -

MIYAKI Yukio (GONG Muduo) 宮木幸雄(龔慕鐸)(B

MIYAKI Yukio (GONG Muduo) 宮木幸雄(龔慕鐸)(b. 1934) Cinematographer Born in Kanagawa Prefecture, Miyaki joined Ari Production in 1952 and once worked as assistant to cinematographer Inoue Kan. He won an award with TV programme Kochira Wa Shakaibu in Japan in 1963. There are many different accounts on how he eventually came to work in Hong Kong. One version has it that he came in 1967 with Japanese director Furukawa Takumi to shoot The Black Falcon (1967) and Kiss and Kill (1967) for Shaw Brothers (Hong Kong) Ltd. Another version says that the connection goes back to 1968 when he helped Chang Cheh film the outdoor scenes of Golden Swallow (1968) and The Flying Dagger (1969) in Japan. Yet another version says that he signed a contract with Shaws as early as 1965. By the mid-1970s, under the Chinese pseudonym Gong Muduo, Miyaki worked as a cinematographer exclusively for Chang Cheh’s films. He took part in over 30 films, including The Singing Thief (1969), Return of the One-armed Swordsman (1969), The Invincible Fist (1969), Dead End (1969), Have Sword, Will Travel (1969), Vengeance! (1970), The Heroic Ones (1970), The New One-Armed Swordsman (1971), The Anonymous Heroes (1971), Duel of Fists (1971), The Deadly Duo (1971), Boxer from Shantung (1972), The Water Margin (1972), Trilogy of Swordsmanship (1972), The Blood Brothers (1973), Heroes Two (1974), Shaolin Martial Arts (1974), Five Shaolin Masters (1974), Disciples of Shaolin (1975), The Fantastic Magic Baby (1975), Marco Polo (1975), 7-Man Army (1976), The Shaolin Avengers (1976), The Brave Archer (1977), The Five Venoms (1978) and Life Gamble (1979). -

Destabilizing Shakespeare: Reimagining Character Design in 1 Henry VI

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Self-Designed Majors Honors Papers Self-Designed Majors 2021 Destabilizing Shakespeare: Reimagining Character Design in 1 Henry VI Carly Sponzo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/selfdesignedhp Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Self-Designed Majors at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Self-Designed Majors Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Connecticut College Destabilizing Shakespeare: Reimagining Character Design in 1 Henry VI A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Student-Designed Interdisciplinary Majors and Minors in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree in Costume Design by Carly Sponzo May 2021 Acknowledgements I could not have poured my soul into the following pages had it not been for the inspiration and support I was blessed with from an innumerable amount of individuals and organizations, friends and strangers. First and foremost, I would like to extend the depths of my gratitude to my advisor, mentor, costume-expert-wizard and great friend, Sabrina Notarfrancisco. The value of her endless faith and encouragement, even when I was ready to dunk every garment into the trash bin, cannot be understated. I promise to crash next year’s course with lots of cake. To my readers, Lina Wilder and Denis Ferhatovic - I can’t believe anyone would read this much of something I wrote. -

New on DVD & Blu-Ray

New On DVD & Blu-Ray The Magnificent Seven Collection The Magnificent Seven Academy Award® Winner* Yul Brynner stars in the landmark western that launched the film careers of Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn. Tired of being ravaged by marauding bandits, a small Mexican village seeks help from seven American gunfighters. Set against Elmer Bernstein’s Oscar® Nominated** score, director John Sturges’ thrilling adventure belongs in any Blu-ray collection. Return of the Magnificent Seven Yul Brynner rides tall in the saddle in this sensational sequel to The Magnificent Seven! Brynner rounds up the most unlikely septet of gunfighters—Warren Oates, Claude Akins and Robert Fuller among them—to search for their compatriot who has been taken hostage by a band of desperados. Guns of the Magnificent Seven This fast-moving western stars Oscar® Winner* George Kennedy as the revered—and feared—gunslinger Chris Adams! When a Mexican revolutionary is captured, his associates hire Adams to break him out of prison to restore hope to the people. After recruiting six experts in guns, knives, ropes and explosives, Adams leads his band of mercenaries on an adventure that will pit them against their most formidable enemy yet! *1967: Supporting Actor, Cool Hand Luke. The Magnificent Seven Ride! This rousing conclusion to the legendary Magnificent Seven series stars Lee Van Cleef as Chris Adams. Now married and working for the law, Adams’ settled life is turned upside-down when his wife is killed. Tracking the gunmen, he finds a plundered border town whose widowed women are under attack by ruthless marauders. -

Hong Kong Filmmakers Search: Eric TSANG

Eric TSANG 曾志偉(b. 1953.4.14) Actor, Director, Producer A native of Wuhua, Guangdong, Tsang was born in Hong Kong. He had a short stint as a professional soccer player before working as a martial arts stuntman at Shaw Brothers Studio along with Sammo Hung. In 1974, he followed Lau Kar-leung’s team to join Chang Cheh’s film company in Taiwan, and returned to Hong Kong in 1976. Tsang then worked as screenwriter and assistant director for Lau Kar-leung, Sammo Hung and Jackie Chan in companies such as Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest. Introduced to Karl Maka by Lau, Tsang and Maka co-wrote the action comedy Dirty Tiger, Crazy Frog! in 1978. Tsang made his directorial debut next year with The Challenger (1979). In 1980, Tsang was invited by Maka to join Cinema City. He became a member of the ‘Team of Seven’, participating in story creation. He soon directed the record shattering Aces Go Places (1982) and Aces Go Places II (1983), while he also produced a number of movies that explored different filmmaking approaches, including the thriller He Lives by Night (1982), Till Death Do We Scare (1982), which applied western style make-up and special effects, and the fresh comedy My Little Sentimental Friend (1984). Tsang left Cinema City in 1985 and became a pivotal figure in Hung’s Bo Ho Films. He was the associate producer for such films as Mr. Vampire (1985) and My Lucky Stars (1985). In 1987, Tsang co-founded Alan & Eric Films Co. Ltd. with Alan Tam and Teddy Robin. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

Cultural Studies and the Un/Popular How the Ass-Kicking Work of Steven Seagal May Wrist- Break Our Paradigms of Culture Dietmar Meinel ‘Steven Seagal. Action Film. USA 2008.’ —German TV Guide The first foreigner to run an aikido dojo in Japan, declared the reincarna- tion of a Buddhist lama, blackmailed by the mob, environmental activist, small-town sheriff, owner of a brand of energy drinks, film producer, writer, musician, and lead in his first film (cf. Vern vii), 1980s martial arts action film star Steven Segal is a fascinating but often contradictory figure. Yet, Seagal is strikingly absent from the contemporary revival of seasoned action-film heroes such as Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Dolph Lundgren, and Chuck Norris in The Expendables (2010), The Expendables 2 (2012), and The Expendables 3 (2014). In contrast, ‘starring’ in up to four direct-to-video releases each year over the last decade, Seagal has become a successful entrepreneur of B movies. The (very) low production values of these films, however, highlight rather than conceal his physical demise as incongruent, confusing, and Godard-style editing replaces the fast-paced martial arts action of earlier movies. While his bulky body has become a disheartening memento of his glorious past, his uncompromising commitment to spiritual enlighten- ment and environmental protection arguably elevates him above the mere ridiculousness of his films. In this essay, I will explore Seagal and his oeuvre as he moved from ac- claimed martial arts action star to bizarre media figure in order to devise a framework for un/popular culture.