Literacy Issues During Changing Times: a Call to Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

The Truth About Reading Recovery® Response to Cook, Rodes, & Lipsitz (2017) from the Reading Recovery Council of North America

The Truth About Reading Recovery® Response to Cook, Rodes, & Lipsitz (2017) from the Reading Recovery Council of North America In an article appearing in Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, authors Cook, Rodes, and Lipsitz (2017) make multiple misleading, misguided, and blatantly false claims about Reading Recovery® in yet another attack to discredit the most widely researched early reading intervention in the world. When you’re recognized as a leader with proven success, you often become the target for those with limited knowledge who apply broad strokes and twist the truth to fit their own perceptions of reality. The unfortunate reality, in this case, is that this article, “The Reading Wars and Reading Recovery: What Educators, Families, and Taxpayers Should Know,” is an affront to researchers, scholars, educators, and others who know the facts and a disservice to parents of children with reading difficulties. The authors claim to provide information necessary to make evidence-based decisions in support of struggling beginning readers. Like evidence-based medicine, these decisions can have a critical impact on children’s lives. As in the medical context, objective professionals can differ in their interpretations of the available evidence. The authors’ perspective is far from objective. They invoke the “reading wars” in their title and advocate for their ideological perspective in their biased, selective, and fallacy-full analysis of Reading Recovery and the research related to this early intervention approach. Dr. Timothy Shanahan, past president of the International Reading Association (now International Literacy Association) and a distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago, noted the effectiveness of Reading Recovery in a recent article examining the importance of replicability in reading research. -

Worried About Word Work? Why, When, and What?

11/2/2016 WORRIED ABOUT WORD WORK? WHY, WHEN, AND WHAT? ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGS Word work is necessary early in lessons for learning to look at print (LLAP) and embedded in continuous texts (reading and writing) in later lessons. What do the word work procedures LOOK LIKE for early and late lessons. Reading Writing WHAT TO DO AND WHEN TO DO IT? We will examine video tapings to see word work in action. We would expect echoes across the lesson. We will use the word work cheat sheet as a guide across this presentation, so please have it handy. 1 11/2/2016 MARIE CLAY WORDS OF WISDOM “If the child has to make a short sharp detour from reading continuous text to study something in isolation, what is learned should soon recur in the context of continuous text because this is what reading books and writing stories is about.” Clay, LLI, Part 1, p. 25 WHOLE TO PART AND BACK TO WHOLE “A detour may help the child to pay attention to some particular aspect of print but, clearly, the detail is of limited value on its own. It must in the end be used in the service of reading and writing continuous text.” Clay, LLI, Part 1, p. 25 A LITTLE BIT OF THEORY – WHY WORD WORK “You relate what you hear or see to things you already understand. The moment of truth is the moment of input, How you attend How much you care How you encode What you do with it And how you organize it. Clay, LLI , Part 2 2 11/2/2016 EARLY LEARNING THE JOURNEY OF A WORD New Only just known Successfully problem-solved Easily produced but easily thrown Well-known and recognized in most context Known in many variant forms. -

'Predicting the Patterns of Early Literacy Achievement

Predicting Patterns of Early Literacy Achievement: A Longitudinal Study of Transition from Home To School Author Young, Janelle Patricia Published 2004 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Cognition, Language and Special Education DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1354 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367304 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Predicting the Patterns of Early Literacy Achievement: A Longitudinal Study of Transition from Home to School VOLUME 1 Janelle Patricia Young DipTch; BEd; MEdSt A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Faculty of Education, School of Cognition, Language and Special Education, Griffith University, Brisbane. July 2003 ABSTRACT This is a longitudinal study of patterns of children's early literacy development with a view to predicting literacy achievement after one year of schooling. The study fits within an emergent/social constructivist theoretical framework that acknowledges a child as an active learner who constructs meaning from signs and symbols in the company of other more experienced language users. Commencing in the final month of preschool, the literacy achievement of 114 young Australian students was mapped throughout Year 1. Data were gathered from measures of literacy achievement with the students, surveys with parents and surveys and checklists with teachers. Cross-time comparisons were possible as data were gathered three times from the students and teachers and twice from parents. Parents’ perceptions of their children’s personal characteristics, ongoing literacy development and family home literacy practices were examined in relation to children’s measures of literacy achievement. -

How and Why Children Learn About Sounds, Letters, and Words in Reading Recovery Lessons

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 437 616 CS 013 828 AUTHOR Fountas, Irene C.; Pinnell, Gay Su TITLE How and Why Children Learn about Sounds, Letters, and Words in Reading Recovery Lessons. INSTITUTION Reading Recovery Council of North America, Columbus, OH. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 12p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) Journal Articles (080) Reports Research (143) JOURNAL CIT Running Record; v12 n1 p1-6,10-11,13-14 Fall 1999 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Beginning Reading; Classroom Research; *Classroom Techniques; Learning Activities; *Learning Processes; *Literacy; Primary Education; Word Recognition IDENTIFIERS Lesson Structure; *Orthography; Phonological Awareness; *Reading Recovery Projects; Word Learning ABSTRACT This article takes a look at Reading Recovery lesson elements to compare the teaching and learning within the lesson components to several areas of learning that have been identified at the national level as important to children's literacy learning. The lesson elements examined in the article are: (1) phonological awareness; (2) orthographic awareness; and (3) word learning in reading and writing. The article states that the first two areas of knowledge, and the way they are interrelated, contribute to young children's growth in the ability to solve words while reading for meaning, while the third area strongly supports learning in the first two areas and also helps to accelerate early learning in literacy. These elements together contribute to the child's development of a larger process in which the reader uses "in-the-head" strategies in an efficient way to access and orchestrate a variety of information, including meaning and language systems, with the visual and phonological information in print. -

A Tribute to Marie M. Clay

Marie Clay: An Honored Mentor, Colleague, and Friend A Tribute to Marie M. Clay: It is an awesome task to describe Marie Clay as a mentor, colleague and friend. She Searched for Questions In my attempt, words fail to capture the extensive and nuanced ways that she impacted and influenced those of us That Needed Answers who were privileged to be mentored and befriended by this remarkable Billie Askew, trainer emeritus, Texas Woman’s University humanitarian. The authors in this section provide insight When I consider Marie Clay’s influ- Marie’s perpetual state of inquiry had into the nature of her learning, thinking, ence on my life, I must return to a profound effect on me. At first, it encouraging, and challenging. We are the late 1960s, long before I knew was not always comfortable when reminded of her never ending search for what is possible. Sailing in new directions her. My advisor and mentor at I was the object of her inquiry and herself, she supported her colleagues to the University of Arizona, literacy wanted to respond with an ‘accept- travel to previously uncharted territory scholar Ruth Strang, talked of visiting able’ if not ‘right’ answer. I had to as well. She provided an outstanding with a young researcher from New abandon some ‘safe havens’ and be example of extraordinary research, borne Zealand at the World Congress in open to new ways of thinking, asking from her keen observations of children’s Copenhagen. Dr. Strang predicted new questions of my own. What a development. She employed unusual lenses to observe and capture change over that this extraordinary thinker would gift she gave me—both professionally time and to reveal to all of us what we contribute to world literacy in ways and personally. -

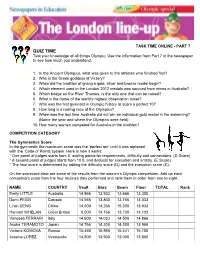

QUIZ TIME Test Your Knowledge of All Things Olympic

TASK TIME ONLINE - PART 7 QUIZ TIME Test your knowledge of all things Olympic. Use the information from Part 7 in the newspaper to see how much you understand. 1. In the Ancient Olympics, what was given to the athletes who finished first? 2. Who is the Greek goddess of Victory? 3. When did the tradition of giving a gold, silver and bronze medal begin? 4. Which element used in the London 2012 medals was sourced from mines in Australia? 5. Which bridge on the River Thames, is the only one that can be raised? 6. What is the name of the world’s highest observation tower? 7. Who was the first gymnast in Olympic history to score a perfect 10? 8. How long is a rowing race at the Olympics? 9. When was the last time Australia did not win an individual gold medal in the swimming? (Name the year and where the Olympics were held) 10. How many women competed for Australia in the triathlon? COMPETITION CATEGORY The Gymnastics Score In the gymnastic the maximum score was the ‘perfect ten’ until it was replaced with the ‘Code of Points system. Here is how it works: * One panel of judges starts from 0, adding points for requirements, difficulty and connections. (D Score) * A second panel of judges starts from 10.0, and deducts for execution and artistry. (E Score) * The final score is determined by adding the difficulty score (D) and the execution score (E). On the scorecard blow are some of the results from the women’s Olympic competition. -

Learning Disabilities-United States

LEARNING The Learning Disabilit Controversy and Composition Studies LEARNING RE-AILED LEARNING RE-AILED The Learning Disability Controversy and Composition Studies Patricia A. Dunn Utica College of Syracuse University Boynton/Cook Publishers HEINEMANN Portsmouth, NH Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc. A subsidiary of Reed Elsevier Inc. 361 Hanover Street Portsmouth, NH 03801-3912 Offices and agents throughout the world © 1995 by Patricia A. Dunn. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders and students for permission to reprint borrowed material. We regret any oversights that may have occurred and would be happy to rectify them in future printings of this work. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunn, Patricia A. Learning re-abled : the learning disability controversy and composition studies / Patricia A. Dunn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-86709-360-9 (alk. paper) 1. Learning disabled-Education (Higher)-United States. 2. Learning disabilities-United States. 3. Dyslexics-Education teaching-United States. I. Title. LC4818.5.D85 1995 371.91-dc20 95-19316 CIP Editor: Peter R. Stillman Production Editor: Renee M. Nicholls Cover Designer: T. Watson Bogaard Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. 99 -

London Matters 02 2013

European Medallists (Junior and Senior) MAG: Daniel Keatings, Max Whitlock, Brinn Bevan, Sam Oldham, Jay Thompson, Frank Baines, Courtney Tulloch, Nile Wilson, Sam Oldham, Daniel Purvis, Theo Seager, Reiss Beckford, Cameron Mackenzie, Samuel Hunter WAG: Beckie Downie, Jocelyn Hunt, Niamh Rippin, Hannah Whelan The English Gymnastics Championships 2013 was Commonwealth Medallists hosted this year at The Europa Gymnastics Centre. MAG: Reiss Beckford, Max Whitlock Len and Yvonne Arnold OBE and their strong volun- WAG: Laura Edwards, Charlotte Lindsley, teer team certainly know how to put on an event. The Niamh Rippin, Beckie Downie championships this year spanned three days and had a huge entry from London Gymnastics Clubs. Scores Youth Olympic Medallists from the event can be found on MAG: Courtney Tulloch, James Hall, Sam Oldham, http://www.gymdata.co.uk/comps.asp Dominick Cunningham, Nile Wilson, Reiss Beckford, Ashley Watson With two World Class gymnasts competing in the WAG: Tyesha Mattis, Teal Grindle, Catherine Lyons American Cup (Kristian Thomas and Gabby Jupp) we were still left with an array of talent. One World, European multi medallist (Louis Smith MBE) off Strictly dancing, another World, European and Commonwealth medallist (Beth Tweddle MBE) off ice skating and flying around you’d think there wouldn’t be much talent left to see but how very wrong you would be. Who would have thought even 10 years ago that we would be hosting an English Championships with so much depth of talent? The calibre of gymnasts really demonstrated the strides forward made by British Gymnastics and their work in partnership with coaches and clubs. -

Introduction and Overview

Introduction Literacy Lessons™ program is an intervention initiative developed by Marie Clay, internationally known researcher in early literacy learning and the prevention of reading and writing difficulties . The Literacy Lessons trademarks are registered and owned in the U .S . by The Ohio State University, which monitors the trademark requirements and issues annual authorization to use the Literacy Lessons trademark to Reading Recovery university training centers and sites in compliance with these standards . Literacy Lessons may also be referred to as LL™ . Note that the logos are registered marks of The Ohio State University and should be accompanied with the circle R (®)symbol . The words Literacy Lessons and the abbreviation LL should be followed by TM (™) . Only licensed sites can use the logos and the name Literacy Lessons to describe their work . Dr . Clay’s four required elements for a recognized Literacy Lessons implementation follow: 1 . Individually designed and individually delivered instruction for students from special populations who are struggling to develop an early literacy processing system 2 . A recognized course for qualified teachers with ongoing professional development 3 . Ongoing data collection, research, and evaluation 4 . Establishment of an infrastructure and standards to sustain the implementation and maintain quality control Standards and Guidelines of Literacy Lessons in the United States {00203356-1} — Updated June 2015 3 This document presents standards (requirements) and guidelines (recommendations) for implementing Literacy Lessons . Implementations in English and in Spanish are collaborative efforts between Reading Recovery/Descubriendo la Lectura university training centers and Reading Recovery/Descubriendo la Lectura teacher leaders 1. It is intended that Literacy Lessons will only be implemented in schools that include Reading Recovery as an early literacy intervention . -

Billboard 1974-08-24

NEWSPAPER Bill The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly August 24, 1974 $1.25 A Billboard Publication Nixon Furore Slows Davis Calls Texaco Sued In Copyright Movement Promo Slot Tape Piracy Test By MILDRED HALL A Hot Seat By STEPHEN Panasonic Sets By IS HOROWITZ TRAIMAN WASHINGTON -The aftermath NEW YORK -In what may develop as a precedent- setting piracy test case, NEW YORK -Promotion is of the Nixon resignation has set in now Custom Publishing Co. and Camad Music Co. have filed suit against Texaco, Expansion Move second only to aecr as the "hot seal" motion a new series of delays in alleging copyright infringement on songs appearing on tapes alleged to be of the rc nrd industry. Clive Davis Congress for all pending copyright Hy RADCLIFFE JOE bootleg reproductions and sold at an Illinois Texaco station. The oil firm has told an audience of mire than at bills -including the general revision NEW YORK -Panasonic Au- 600 denied the allegations. the opening session of Billboard's bill 5.1361, the House antipiracy bill tomotive Products Dept. will utilize A ruling for the plaintiffs could seventh Annual International Radio H.R. 13364. and the hoped -for ex- network television, as well as trade UA Restructures establish the important precedent in Programming Forum here Wednes- tension legislation to save expiring and consumer print media- in a mas- piracy litigation of a parent com- copyrights. sive promotion campaign that Cal day (14). Into 5 Divisions pany being held liable for actions of Released from the harrowing job Shore, vice president and general The acting Bell Records chief, in By NAT ERI'EDI.AND its agents -in this' case, an ail com- of impeaching a president, both manager of Panasonic's special his first major address to an industry LOS ANGELES- United Artists pany held accountable for activities a the Senate and House began lengthy products division, tails a major in- audience since leaving presi- bas reorganized its non -film oper- of its franchised stations. -

MEDIA GUIDE BRITISH GYMNASTICS MEDIA GUIDE 45Th WORLD ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS Nanning CHN, 3-12 October 2014

45th WORLD ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS Nanning CHN 3rd - 12th October 2014 MEDIA GUIDE BRITISH GYMNASTICS MEDIA GUIDE 45th WORLD ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS Nanning CHN, 3-12 October 2014 Table of Contents: 1 Introduction 2 2014 Artistic Gymnastics World Championships Nanning, CHN Dates, Competition venue, Contacts 3 Media Accreditation Media Contacts Media Updates 4 GBR Team 5 Competition Schedule 6 The Ascent to Glory - A decade of British Gymnastics (1999-2013) 9 The British World Medal Tally 12 Best Individual achievements 12 Best Team achievements men & women 12 The London 2012 Olympic Games – GB Team Results 12 Artistic Gymnastics – apparatus, scoring and judging 13 Recent Results 17 2013 World Championships Antwerp (BEL) 2014 European Championships Sofia (BUL) 2011 World Championships Tokyo (JPN) 18 2012 Olympic Games London (GBR) 23 1 Introduction: British Gymnastics is pleased to present its 2014 Media Guide – Artistic Gymnastics which has been compiled to assist the press and media in covering the performances of British gymnasts at the Artistic Gymnastics World Championships in Nanning (CHN). Any comments, suggestions or feedback on this guide can be provided to: Vera Atkinson Media Specialist British Gymnastics E: [email protected] Nanning 2014 – First Olympic Qualifications round for Rio 2016 Halfway between London 2012 and Rio 2016 these World Championships will serve as the first “sieve” through to the next Olympic Games in Brazil. With rejuvenated teams from all over the world and new International Codes of Points for men and for women, this event will indicate what could happen in Rio in two years’ time. Only the top 24 teams for men and for women in Nanning will qualify to the second Olympic Qualification stage – the World Championships in Glasgow in 2015 where the top eight men's and women's teams will qualify automatically for the Rio Olympics.