Activision: a New Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Grand Theft Archive': a Quantitative Analysis of the State of Computer

Gooding, P. and Terras, M. (2008) "„Grand Theft Archive‟: a quantitative analysis of the current state of computer game preservation". The International Journal of Digital Curation. Issue 2, Volume 3, 2008. http://www.ijdc.net/ijdc/article/view/85/90 1 ‘Grand Theft Archive’: A Quantitative Analysis of the Current State of Computer Game Preservation Paul Gooding, Librarian, BBC Sports Library, London Melissa Terras, School of Library, Archive and Information Studies, University College London November 2008 Abstract Computer games, like other digital media, are extremely vulnerable to long-term loss, yet little work has been done to preserve them. As a result we are experiencing large-scale loss of the early years of gaming history. Computer games are an important part of modern popular culture, and yet are afforded little of the respect bestowed upon established media such as books, film, television and music. We must understand the reasons for the current lack of computer game preservation in order to devise strategies for the future. Computer game history is a difficult area to work in, because it is impossible to know what has been lost already, and early records are often incomplete. This paper uses the information that is available to analyse the current status of computer game preservation, specifically in the UK. It makes a quantitative analysis of the preservation status of computer games, and finds that games are already in a vulnerable state. It proposes that work should be done to compile accurate metadata on computer games and to analyse more closely the exact scale of data loss, while suggesting strategies to overcome the barriers that currently exist. -

Activision Case Study

RIVERSTAR.COM ACTIVISION CASE STUDY Entertainment Publisher uses RiverStar to Streamline Returns CHALLENGE Activision inherited the Guitar Hero brand through their acquisition of ABOUT ACTIVISION RedOctane. Activision was unfamiliar with warranty replacements required Headquartered in Santa Monica, California, from hardware games and for that reason, relied on legacy processes Activision Blizzard, Inc. is the world’s developed by RedOctane. Because RedOctane’s processes were mostly largest pure-play interactive entertainment manual, with no troubleshooting, Activision customers would be referred to software publisher with leading market RedOctane’s website for warranty support. For some games, the customer had positions across all categories of the growing to email a copy of the receipt, further delaying the time to process the claim. interactive entertainment software industry. The customer could call RedOctane for warranty support, but due to limited Activision is the video game publisher that resources, call handle times were very high. The resulting outcome was a large is best known for game franchises such as number of dissatisfied customers with the RedOctane warranty process. World of Warcraft, Guitar Hero, Tony Hawk With the growing popularity of gaming products with hardware components Ride and Call of Duty. With global operations and a pipeline of new hardware games on the horizon, Activision was tasked in 13 countries, Activision has grown into a with creating a new process that would be automated throughout the $5 billion video game powerhouse. company to provide a better customer experience. The Guitar Hero franchise continues to In addition to working with new warranty support processes, the Guitar Hero redefine gaming by delivering innovative World Tour game was released just before the busy 2008 holiday season. -

Doom: Gráficos Avançados E Atmosfera Sombria

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL TECNOLOGIAS DE CONTATO: OS IMPACTOS DAS PLATAFORMAS DOS JOGOS DIGITAIS NA JOGABILIDADE SOCIAL CHRISTOPHER ROBERT KASTENSMIDT Professora Orientadora: Dra. Magda Rodrigues da Cunha Porto Alegre Dezembro/2011 CHRISTOPHER ROBERT KASTENSMIDT TECNOLOGIAS DE CONTATO: OS IMPACTOS DAS PLATAFORMAS DOS JOGOS DIGITAIS NA JOGABILIDADE SOCIAL Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação Social da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Orientadora: Dra. Magda Rodrigues da Cunha PORTO ALEGRE 2011 CHRISTOPHER ROBERT KASTENSMIDT Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) K19t Kastensmidt, Christopher Robert Tecnologias de contato: os impactos das plataformas dos jogos digitais na jogabilidade social. / Christopher Robert Kastensmidt. – Porto Alegre, 2011. 172 p. Dissertação (Mestrado) Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação Social – Faculdade de Comunicação Social, PUCRS. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Magda Rodrigues da Cunha 1. Comunicação Social. 2. Jogos Digitais. 3. Jogabilidade Social. 4. Jogos Eletrônicos. I. Cunha, Magda Rodrigues da. II. Título. CDD 794.8 Ficha elaborada pela bibliotecária Anamaria Ferreira CRB 10/1494 TECNOLOGIAS DE CONTATO: OS IMPACTOS DAS PLATAFORMAS DOS JOGOS DIGITAIS NA JOGABILIDADE SOCIAL Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação Social -

The Golden Age of Video Games

The Golden Age of Video Games The Birth of a Multi-Billion Dollar Industry The Golden Age of Video Games The Birth of a Multi-Billion Dollar Industry Roberto Dillon CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2011 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Version Date: 20130822 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4398-7324-3 (eBook - PDF) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, trans- mitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright. com (http://www.copyright.com/) or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. -

The New Zork Times Dark – Carry a Lamp VOL

“All the Grues New Zork Area Weather: That Fit, We Print” The New Zork Times Dark – carry a lamp VOL. 3. .No. 1 WINTER 1984 INTERNATIONAL EDITION SORCERER HAS THE MAGIC TOUCH InfoNews Roundup New Game! Hint Booklets Sorcerer, the second in the In December, Infocom's long- Enchanter series of adventures in the awaited direct mail operation got mystic arts, is now available. The underway. Many of the functions game was written by Steve formerly provided by the Zork Users Meretzky, whose hilarious science Group were taken over by Infocom. fiction game, Planetfall, was named Maps and InvisiClues hint booklets by InfoWorld as the Best Adventure were produced for all 10 of Game of 1983. In Sorcerer, you are a Infocom's products. The games member of the prestigious Circle of themselves were also made available Enchanters, a position that you primarily as a service to those of you achieved in recognition of your in remote geographical areas and to success in defeating the Warlock those who own the less common Krill in Enchanter. computer systems. When the game starts, you realize Orders are processed by the that Belboz, the Eldest of the Circle, Creative Fulfillment division of the and the most powerful Enchanter in DM Group, one of the most the land, has disappeared. Perhaps he respected firms in direct mail. Their has just taken a vacation, but it facilities are in the New York metro- wouldn't be like him to leave without politan area, which explains the letting you know. You remember strange addresses and phone num- that he has been experimenting with bers you'll see on the order forms. -

Guitar Hero® Live Puts Fans in the Game with Crowd-Sourced Music Video for Ed Sheeran's "Sing"

Guitar Hero® Live Puts Fans in the Game with Crowd-Sourced Music Video for Ed Sheeran's "Sing" "Guitar Hero TV Star" Gives Fans the Chance to Star in the First User-Generated Music Video for Guitar Hero Live with the World Premiere Video Playable in the Game Fans to Submit Lip-Synching Clips through the Popular musical.ly Mobile App SANTA MONICA, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- In celebration of the highly anticipated return of Guitar Hero, Activision Publishing, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, Inc. (NASDAQ: ATVI), is partnering with crowd-sourced music video creation app musical.ly to kick off Guitar Hero TV Star, which will ask fans to submit clips of themselves singing and dancing along to Ed Sheeran's hit song "Sing." The end result will be a world premiere, user-generated music video in GHTV, Guitar Hero Live's playable music video network. "Guitar Hero Live gives you the thrill of being a rock star by playing in front of real crowds or awesome music videos, so we wanted to give fans the opportunity to become stars of their own music video that will be featured and playable in the game. This is something that has never been done before, and we believe it is the perfect way to celebrate the launch of the game," said Tim Ellis, CMO of Activision Publishing, Inc. "With GHTV, the game's online playable music video network, we can deliver all kinds of gameplay experiences that just weren't possible in the past. To put real fans into a video that people can play along to in the game is an expression of the innovation that we have built into Guitar Hero Live, and we're excited for fans to play along - and sing along - to the music." "Guitar Hero and musical.ly share a similar vision to make music more participatory and interactive," said Jun Zhu, co-founder and co-CEO of musical.ly. -

Investor Presentation

Investor presentation May 2021 Disclaimer In this strategic presentation, the terms "Atari“ and/or the "Company" mean Atari. The term "Group" means the group of companies belonging to the parent Company and all companies within its consolidation’s scope. This strategic presentation contains statements relating to ongoing or future projects, future financial and operating results and other statements about Atari’s managements’ future expectations, beliefs, goals, plans or prospects that are based on current expectations, estimates, forecasts and projections about Atari, as well as company’s future performance and the industries in which Atari operate will operate, in addition to managements’ assumptions. Words such as “expects,” “anticipates,” “targets,” “goals,” “projects,” “intends,” “plans,” “believes,” “seeks,” “estimates,” variations of such words and similar expressions are intended to identify such forward-looking statements which are not statements of historical facts. These forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and involve certain risks, uncertainties and assumptions that are difficult to assess. Therefore, actual outcomes and results may differ materially from what is expressed or forecasted in such forward-looking statements. These risks and uncertainties are based upon a number of important factors including, among others: political and economic risks of our respective global operations; changes to existing regulations or technical standards; existing and future litigation; difficulties and costs in protecting intellectual property rights and exposure to infringement claims by others summarized in chapter 5 of the company’s annual financial report for the financial year ended March 31, 2020 available on the investor relations website of Atari at www.atari- investisseurs.fr. -

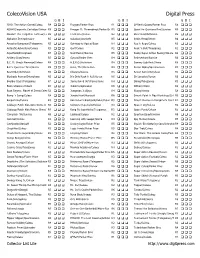

Dp Guide Lite Us

ColecoVision USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 2010: The Action Game/Coleco R4 Frogger/Parker Bros R1 Q*Bert's Qubes/Parker Bros R8 ADAM Diagnostic Cartridge/Coleco R9 Frogger II: Threeedeep!/Parker Br R5 Quest for Quintana Roo/Sunrise R5 Alcazar: The Forgotten Fortress/Te R2 Front Line/Coleco R2 River Raid/Activision R2 Alphabet Zoo/Spinnaker R5 Galaxian/Atarisoft R5 Robin Hood/Xonox R6 Amazing Bumpman/Telegames R5 Gateway to Apshai/Epyx R4 Roc ‘n Rope/Coleco R3 Antarctic Adventure/Coleco R3 Gorf/Coleco R2 Rock 'n Bolt/Telegames R2 Aquattack/Interphase R7 Gust Buster/Sunrise R5 Rocky Super Action Boxing/Coleco R2 Artillery Duel/Xonox R5 Gyruss/Parker Bros R4 Rolloverture/Sunrise R6 B.C. II: Grog's Revenge/Coleco R4 H.E.R.O./Activision R4 Sammy Lightfoot/Sierra R8 B.C.'s Quest for Tires/Sierra R3 Heist, The/Micro-Fun R4 Sector Alpha/Spectravision R7 Beamrider/Activision R4 Illusions/Coleco R5 Sewer Sam/Interphase R5 Blockade Runner/Interphase R6 It's Only Rock 'n Roll/Xonox R6 Sir Lancelot/Xonox R6 Boulder Dash/Telegames R7 James Bond 007/Parker Bros R4 Skiing/Telegames R5 Brain Strainers/Coleco R5 Jukebox/Spinnaker R6 Slither/Coleco R2 Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom/Colec R2 Jumpman Jr./Epyx R4 Slurpy/Xonox R8 Bump 'n Jump/Coleco R4 Jungle Hunt/Atarisoft R6 Smurf: Paint 'n Play Workshop/Col R5 Burgertime/Coleco R3 Ken Uston's Blackjack/Poker/Colec R3 Smurf: Rescue in Gargamel's Castl R1 Cabbage Patch Kids Adventures in R3 Keystone Kapers/Activision R3 Space Fury/Coleco R2 Cabbage Patch -

Elec~Ronic Gantes Formerly Arcade Express

Elec~ronic Gantes Formerly Arcade Express Tl-IE Bl-WEEKLY ELECTRONIC GAMES NEWSLETTER VOLUME TWO, NUMBER NINE DECEMBER 4, 1983 SINGLE ISSUE PRICE $2.00 ODYSSEY EXITS The company that created the home arcading field back in 1970 has de VIDEOGAMING cided to pull in its horns while it takes its future marketing plans back to the drawing board. The Odyssey division of North American Philips has announced that it will no longer produce hardware for its Odyssey standard programmable videogame system. The publisher is expected to play out the string by market ing the already completed "War Room" and "Power Lords" cartridges for ColecoVision this Christmas season, but after that, it's plug-pulling time. Is this the end of Odyssey as a force in the gaming world? Only temporarily. The publisher plans to keep a low profile for a little while until its R&D department pushes forward with "Operation Leapfrog", the creation of N.A.P. 's first true computer. 20TH CENTURY FOX 20th Century Fox Videogames has left the game business, saying, THROWS IN THE TOWEL "Enough is enough!" According to Fox spokesmen, the canny company didn't actually experience any heavy losses. However, the foxy powers-that-be decided that the future didn't look too bright for their brand of video games, and that this is a good time to get out. The company, whose hit games included "M*A*S*H", "MegaForce", "Flash Gordon" and "Alien", reportedly does not have a large in ventory of stock on hand, and expects to experience no large financial losses as it exits the gaming business. -

Gamasutra - Features - the History of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM

Gamasutra - Features - The History Of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM The History Of Activision By Jeffrey Fleming The Memo When David Crane joined Atari in 1977, the company was maturing from a feisty Silicon Valley start-up to a mass-market entertainment company. “Nolan Bushnell had recently sold to Warner but he was still around offering creative guidance. Most of the drug culture was a thing of the past and the days of hot-tubbing in the office were over,” Crane recalled. The sale to Warner Communications had given Atari the much-needed financial stability required to push into the home market with its new VCS console. Despite an uncertain start, the VCS soon became a retail sensation, bringing in hundreds of millions in profits for Atari. “It was a great place to work because we were creating cutting-edge home video games, and helping to define a new industry,” Crane remembered. “But it wasn’t all roses as the California culture of creativity was being pushed out in favor of traditional corporate structure,” Crane noted. Bushnell clashed with Warner’s board of directors and in 1978 he was forced out of the company that he had founded. To replace Bushnell, Warner installed former Burlington executive Ray Kassar as the company’s new CEO, a man who had little in common with the creative programmers at Atari. “In spite of Warner’s management, Atari was still doing very well financially, and middle management made promises of profit sharing and other bonuses. Unfortunately, when it came time to distribute these windfalls, senior management denied ever making such promises,” Crane remembered. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Jay Simon 3/18/2002 STS 145 Case Study Zork: a Study of Early

Jay Simon 3/18/2002 STS 145 Case Study Zork: A Study of Early Interactive Fiction I: Introduction If you are a fan of interactive fiction, or have any interest in text-based games from the early 1980’s, then you are no doubt familiar with a fascinating series known as Zork. For the other 97 percent of the population, the original Zork games are text-based adventures in which the player is given a setting, and types in a command in standard English. The command is processed, and sometimes changes the state of the game. This results in a new situation that is then communicated to the user, restarting the cycle. This type of adventure game is classified as belonging to a genre called “interactive fiction”. Zork is exceptional in that the early Zork games are by far the most popular early interactive fiction titles ever released. It is interesting to examine why these games sold so well, while most other interactive fiction games could not sell for free in the 1980’s. As we will see, this is a result of many different technological and stylistic aspects of Zork that separate it from the rest of the genre. Zork is a unique artifact in gaming history. II: MIT and Infocom – The Prehistory of Zork Zork was not a modern project developed under a strict timeline by a designated team of programmers, but credit is given to two MIT phenoms named Marc Blank and Dave Lebling. Its history can be traced all the way back to the invention of a medium-sized machine called the PDP-10, in the 1960’s.