Linda Connor and Adrian Vickers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

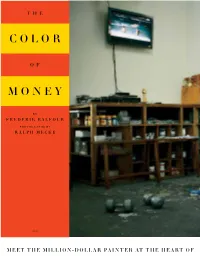

The-Color-Of-Money.Pdf

POURS TWO GLASSES FROM A BOTTLE OF 18-YEAR-OLD MACALLAN single-malt Scotch. He’s sitting poolside at his 1,000-square- meter villa on the outskirts of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, the eve- ning air rich with jasmine, frangipani and passion fruit, mingled with the sweet smoke from Masriadi’s clove cigarette. A shiny, new, 1,700-cubic-centimeter Harley-Davidson motor- cycle is parked at one end of his garden; a Balinese-style gazebo and shrine stand at the other. “Perhaps I have had success in my career,” the 40-year-old artist says. Masriadi is being modest. Fifteen years ago, he was hawking souvenir paintings to tourists in Bali for $20 a pop. Today, his canvases sell at blue-chip galleries for $250,000 to $300,000, and he’s the first living Southeast Asian artist whose work has topped $1 million at auction. Hence the Harley, the pool and the expensive Scotch. An obsessive and painstakingly slow painter, Masriadi turns out only eight to 10 canvases a year. His style is a cross between DC Comics (home to Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman), which he acknowledges as an inspiration, and the Colombian painter and sculptor Fernando Botero, whom he does not. Me- ticulously executed and ironic, his works feature preternatu- rally muscular figures with gleaming skin. His themes range from mobile phones and online gaming to political corruption and the pain of dieting. Deceptively simple at first glance, his works often evince trenchant political satire. Nicholas Olney, director of New York’s Paul Kasmin Gallery, recalls seeing an exhibition of the artist’s work for the first time at the Singapore Art Museum in 2008. -

Archival Pigment Print on Aluminum Protected with Transparent Acrylic 120 X 150 Cm Agan Harahap

Agan Harahap Old Master 2016 | Archival pigment print on aluminum protected with transparent acrylic 120 x 150 cm Agan Harahap Bounty Hunter 2016 | Archival pigment print on aluminum protected with transparent acrylic 155 x 100 cm Di era teknologi digital ini, citra menyebar di dunia maya secepat cahaya. Kecepatan, ilusi dan kesolidan realitas maya membuat kita kerap merasakannya sebagai realitas sesungguhnya. Tanpa pernah menyaksikan lukisan aslinya dan merasa berjarak dengan paradigma dunia seni ‘tinggi’ di Indonesia, Agan Harahap menemukan citra sosok-sosok karikatural yang dikenal sebagai identitas “blue-chip” lukisan Nyoman Masriadi. Lukisan- lukisan bercitra koboi-pemburu dan kesatria mirip samurai itu tahun lalu dipajang di sebuah galeri terkenal di New York. Agan Harahap “melukis” atau menafsir ulang citraan mashyur itu dengan perangkat lunak komputer. Kejanggalan yang ditemukan pada lukisan Masriadi diperbaiki menjadi citra fotografis yang lebih ‘sempurna’ dengan merekayasa sejumlah foto rujukan dan model citra temuan. Kendati tetap condong sebagai fiksi, karyanya memberi asosiasi tokoh yang benar-benar ada di dunia nyata. Karya olahan fotografinya menjadi parodi dari citra lukisan yang—entah dengan mekanisme apa—ditahbiskan sebagai “kandidat apresiasi” yang bernilai sangat tinggi. In this era of digital technology, an image multiplies in the virtual world in the speed of light. The speed, the illusion and the solidity of virtual world make us often feel it as a true reality. Since he never watched the real painting and still feels a distance from the paradigm of "high" art world in Indonesia, Agan Harahap found the image of caricature figures known as the "blue-chip" identity of Nyoman Masriadi's painting. -

Art Turns. World Turns

Art Turns. World Turns. Exploring the Collection of The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara 4 November 2017 — 18 March 2018 Daftar Isi Published for Art Turns. World Turns. Exploring the Collection of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara, an exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara ( Museum MACAN ) Content and held on 4 November 2017 to 18 March 2018 Publisher : The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (Museum MACAN) AKR Tower, Level MM Jl. Panjang No. 5 Kebon Jeruk Jakarta Barat 11530, Indonesia Phone. +62 21 2212 1888 10 96 Email. [email protected] www.museummacan.org Sekapur Sirih Karya Foreword Plates Curators: Charles Esche and Agung Hujatnika — Fenessa Adikoesoemo Copyright Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara, 2017 14 192 Buku ini memiliki hak cipta. Dilarang menerbitkan ulang sebagian atau seluruhnya tanpa ijin tertulis dari penerbit. Tidak ada ilustrasi dalam publikasi ini yang dapat Pengantar Katalog Karya diterbitkan ulang tanpa ijin pemilik hak cipta. Seluruh permintaan yang berkaitan Introduction Catalog of Works dengan penerbitan ulang dan hak cipta harus ditujukan kepada penerbit. — Aaron Seeto This work is copyright. No part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. No illustration in this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the copyright owners. Requests and inquiries concerning reproductions 20 200 and rights should be addressed to the publisher. Seni Berubah. Dunia Berubah. Ucapan Terima Kasih Hak cipta atas seluruh teks dalam publikasi ini dimiliki para penulis dan Museum MACAN. Art Turns. World Turns. -

Report on the AIIA Vic Study Tour to Indonesia June 2019

Report on the AIIA Vic Study Tour to Indonesia June 2019 Networking Reception in Yogyakarta Report - AIIA Study Tour to Indonesia June 2019 Dear Reader, We arrived in Indonesia with open minds. We came from all States in Australia, except South Australia. We were a very eclectic group of Australians with many different backgrounds, ages and interests. This meant that we saw the same things and heard the same things but through different lenses. This deepened our understanding of Indonesia. The list of all Delegates are appended to this report. We were very well received wherever we went. Our Australian Missions in Indonesia were most helpful. We met with numerous peoples and organisations. These too are listed in this report. Despite taking six internal flights, we saw very little of this very large and diverse country; seeing only Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Makassar and Toraja. And yet, from those visits, we gleaned so much about this most wonderful country. We were fortunate in having briefing materials prior to our departure. The headings of these are appended to this report. We came away from Indonesia optimistic about its future; marvelling at the opportunities it has and the challenges it faces. We nevertheless carry a disappointment in that Australians have a pitiful knowledge about Indonesia. We came away with the understanding that Australians must implement changes to ensure that Indonesia and Australia can only go into the future, hand in hand, if we, in Australia, are determined to inform ourselves better, much better, about our most important neighbour. I hope that this report does something towards achieving that. -

The Edge Auction Southeast Asian Art

THE EDGE AUCTION SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART SUNDAY, 20 MARCH 2016 ARTWORK DETAIL: LOT 129 | KEN YANG | THE MALAYSIAN MONA LISA | 2013 2016 SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART AUCTION PREVIEWS KUALA LUMPUR PENANG KUALA LUMPUR 20 MARCH 2016 | 1PM 5 & 6 MARCH 2016 | 10.30AM – 6.30PM 12 – 18 MARCH 2016 | 11AM – 7PM Hilton Kuala Lumpur THE LIGHT COLLECTION III Club House White Box @ Publika Shopping Gallery Ballroom A, 3 Jalan Stesen Sentral 1 Jalan Pantai Sinaran Level G2, Block A5, 1 Jalan Dutamas 1 50470, Kuala Lumpur 11700 Gelugor, Penang Solaris Dutamas, 50480 Kuala Lumpur G5-G6, Mont’Kiara Meridin, 19 Jalan Duta Kiara, Mont’Kiara, 50480 Kuala Lumpur T: +6-03-7721 8188 [email protected] www.theedgegalerie.com Supported by 1 MESSAGE REALISTIC PRICES Welcome to our fourth annual art auction this year, which off ers 150 lots, artists, such as Zulkifl i Yusoff , Ahmad Zakii Anwar, Jalaini Abu Hassan, including some of the choicest works available in Southeast Asia. On of- Chong Siew Ying, Yusof Majid, Ahmad Shukri Mohamed and Fauzul Yusri, fer is a mix of paintings, drawings, etchings and sculptures by stalwarts as not forgetting Southeast Asia’s leading watercolourist Chang Fee Ming, well as contemporary stars of the art world. who is based in Terengganu. Due to the prevailing cautious market sentiment in the region, auc- Th is year, we are also off ering sculptures by such established artists tion consignors are more realistic in assessing the value of their prized as Mali Ali Mat Som and Raja Shahriman Raja Aziddin. artworks. Such a situation in the last quarter of 2015 has led to more at- For collectors of portraiture, Paris-based Malaysian artist Ken tractive price estimates for major works by some of the most desirable Yang’s Th e Malaysian Mona Lisa is the top draw in this auction. -

For Immediate Release CONTEMPORARY INDONESIA Private View

For Immediate Release CONTEMPORARY INDONESIA Private view: 18 June 2012, 6-8pm Running Dates: 19 June– 4 August 2012 This exhibition is held in collaboration with Matthias Arndt. Ben Brown Fine Arts, London, is proud to present Contemporary Indonesia, a group exhibition of Indonesia’s most seminal and talented artists. The artistic production and innovation emanating from Indonesia, one of the most culturally and religiously diverse countries in the world, is staggering. In the last two decades, Indonesia has experienced major political change and globalization, resulting in more provocative, challenging and critical work from its artists. While Indonesia has always had a rich artistic tradition, with many artists forming collaboratives and exhibition spaces on the islands of Java and Bali in particular, it is only the last two decades that the market and audience for their work have expanded globally. The artists included in this exhibition are FX Harsono, Nyoman Masriadi, Eko Nugroho, J. Ariadhitya Pramuhendra, Agus Suwage, Ugo Untoro, Entang Wiharso and Yunizar. FX Harsono (born 1949) is known for critically addressing Indonesian political and social issues and is particularly interested in notions of self-identity. Born in the village of Blitar to Chinese-Indonesian parents, Harsono reflects upon the history and injustices of Chinese-Indonesian minorities in his powerful body of work, which includes painting, installations and videos. His latest works focus on writing his Chinese name, in response to a series of laws President Suharto enacted during his regime (1967-1998) that restricted the practice of Chinese customs and religion to private domains and forced Chinese-Indonesians to change their names to Indonesian-sounding names. -

16 February 2020 Rooted in Bali

During Sukarno’s era, the direction of artists who studied outside Bali were same kind of feeling can also be found be different in their artistic approaches Cyanotype. Using images he found on Balinese art has a different agenda, I Made Wianta, Nyoman Gunarsa, in his other painting entitled Dream as well as the narratives, but they do the Internet, he composes them on not in the direction of art history. I Wayan Sika, Pande Gede Supada, Island. Through Wianta’s composition have one thing in common that really his computer and transfers them onto “That agenda was to present a positive and I Nyoman Arsana. They were of colors and dots, we could sense the caught my attention. It is the fact that a large film, which he uses to create image of Indonesia as a new nation on the pioneers of Sanggar Dewata spirit of Bali. both artists do not show any sense his cyanotype print on canvas. Finally, the international stage ... For Sukarno, Indonesia. As recorded by Richard of perspective in their paintings. The he lays acrylic paint onto the canvas the Mooi Indië view was easier to Horstman, “These artists were Similar sensibilities are also evident in composition of their paintings are flat to colour parts of his cyanotype print. integrate into the national story young and dynamic and they loved the works of I Made Djirna presented which is similar to Balinese ornaments As part of the Hindu community, he than complicated and challenging to experiment with new techniques in this exhibition, entitled Men and or the traditional Kamasan paintings. -

BKI 169 04 565-568 BR13 Van Der Meij.Indd

Book Reviews 565 Adrian Vickers, Balinese Art: Paintings and Drawings of Bali 1800-2010. Tokyo/ Rutland, Vermont/Singapore: Tuttle, 2012, 256 pp. ISBN 9780804842488. Price: AUD 54.99 (hardback). Balinese art, and especially Balinese paintings cannot complain of not having received much attention in the past or today. Books and articles on Balinese paintings, both those produced in Bali and abroad give us some- times a clear and insightful picture of what this art is about whereas many others continue the dreamlike notions of the unspoiled Balinese who are all artists and paint in a way that take us away from reality to a utopian otherworld. Illustrations of Balinese paintings are, of course, to be found in books on this kind of art and especially nowadays for modern paintings and old paintings alike in the many auction catalogues ranging from Chris- ties and Sotheby’s to Borobudur and Siddharta’s Affordable Art Auctions in Jakarta. Balinese paintings, regardless when they were made may make huge prices in the international art market and have thus now entered a completely new world. From predominantly having been housed in muse- ums of ethnography and in private collections of connoisseurs, they now more and more enter the international commercial art market. Few authors are brave enough to measure Balinese art for what it really is: 90 per cent, and probably more, is produced for ignorant tourists who want to buy something affordable they can easily take home. They want to buy something recognizably Balinese and thus tourist paintings portray ceremonies, naked female torsos and depictions of the Balinese landscape. -

Socio-Political Criticism in Contemporary Indonesian Art

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 Socio-Political Criticism in Contemporary Indonesian Art Isabel Betsill SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Art and Design Commons, Art Practice Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Graphic Communications Commons, Pacific Islands Languages and Societies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Betsill, Isabel, "Socio-Political Criticism in Contemporary Indonesian Art" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3167. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3167 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOCIO-POLITICAL CRITICISM IN CONTEMPORARY INDONESIAN ART Isabel Betsill Project Advisor: Dr. Sartini, UGM Sit Study Abroad Indonesia: Arts, Religion and Social Change Spring 2019 1 CONTEMPORARY INDONESIAN ART ABOUT THE COVER ART Agung Kurniawan. Very, Very Happy Victims. Painting, 1996 Image from the collection of National Heritage Board, Singapore Agung Kurniawan is a contemporary artist who has worked with everything from drawing and comics, to sculpture to performance art. Most critics would classify Kurniawan as an artist-activist as his art pieces frequently engages with issues such as political corruption and violence. The piece Very, Very happy victims is about how people in a fascist state are victims, but do not necessarily realize it because they are also happy. -

Adrian Vickers, Balinese Art: Paintings and Drawings of Bali 1800-2010

Book Reviews 565 Adrian Vickers, Balinese Art: Paintings and Drawings of Bali 1800-2010. Tokyo/ Rutland, Vermont/Singapore: Tuttle, 2012, 256 pp. ISBN 9780804842488. Price: AUD 54.99 (hardback). Balinese art, and especially Balinese paintings cannot complain of not having received much attention in the past or today. Books and articles on Balinese paintings, both those produced in Bali and abroad give us some- times a clear and insightful picture of what this art is about whereas many others continue the dreamlike notions of the unspoiled Balinese who are all artists and paint in a way that take us away from reality to a utopian otherworld. Illustrations of Balinese paintings are, of course, to be found in books on this kind of art and especially nowadays for modern paintings and old paintings alike in the many auction catalogues ranging from Chris- ties and Sotheby’s to Borobudur and Siddharta’s Affordable Art Auctions in Jakarta. Balinese paintings, regardless when they were made may make huge prices in the international art market and have thus now entered a completely new world. From predominantly having been housed in muse- ums of ethnography and in private collections of connoisseurs, they now more and more enter the international commercial art market. Few authors are brave enough to measure Balinese art for what it really is: 90 per cent, and probably more, is produced for ignorant tourists who want to buy something affordable they can easily take home. They want to buy something recognizably Balinese and thus tourist paintings portray ceremonies, naked female torsos and depictions of the Balinese landscape. -

Balinese Art Versus Global Art1 Adrian Vickers 2

Balinese Art versus Global Art1 Adrian Vickers 2 Abstract There are two reasons why “Balinese art” is not a global art form, first because it became too closely subordinated to tourism between the 1950s and 1970s, and secondly because of confusion about how to classify “modern” and “traditional” Balinese art. The category of ‘modern’ art seems at first to be unproblematic, but looking at Balinese painting from the 1930s to the present day shows that divisions into ‘traditional’, ‘modern’ and ‘contemporary’ are anything but straight-forward. In dismantling the myth that modern Balinese art was a Western creation, this article also shows that Balinese art has a complicated relationship to Indonesian art, and that success as a modern or contemporary artist in Bali depends on going outside the island. Keywords: art, tourism, historiography outheast Asia’s most famous, and most expensive, Spainter is Balinese, but Nyoman Masriadi does not want to be known as a “Balinese artist”. What does this say about the current state of art in Bali, and about Bali’s recognition in global culture? I wish to examine the post-World War II history of Balinese painting based on the view that “modern Balinese” art has lost its way. Examining this hypothesis necessitates looking the alternative path taken by Balinese 1 This paper was presented at Bali World Culture Forum, June 2011, Hotel Bali Beach, Sanur. 2 Adrian Vickers is Professor of Southeast Asian Studies and director of the Australian Centre for Asian Art and Archaeology at the University of Sydney. A version of this paper was given at the Bali World Culture Forum, June 2011. -

An Examination of the Significance of Soviet Socialist Realist Art and Practice in the Asia Pacific Region

An examination of the significance of Soviet Socialist Realist art and practice in the Asia Pacific region. Alison Carroll Student Number: 196621690 ORCID Number: 0000-0001-8068-2694 Thesis Submission for Doctor of Philosophy degree October 2016 This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the degree. School of Culture and Communication University of Melbourne Supervisors: Associate Professor Alison Inglis (University of Melbourne) Professor Anthony Milner (University of Melbourne and Australian National University) 1 An examination of the significance of Soviet Socialist Realist art and practice in the Asia Pacific region. Table of contents: 2 Abstract 4 Declaration 5 Acknowledgements 6 List of illustrations 7 Preface 20 Introduction: Western art historical practice and recent Asian art; some alternative ways of thinking. 22 1. Art and politics: Soviet Socialist Realism and art history in the Asia Pacific region. 46 2. Policy and practice: The significance of the new policies and practices created in the Soviet Union in the direction for art in Asia. 70 1. Political leaders on art 70 2. Arts leaders on politics 77 3. The Soviet practice of art in Asia: organisation 80 4. The Soviet practice of art in Asia: ideological innovations 95 5. The transmission of information from West to East 103 3. The Art: The influence of Soviet Socialist Realism on the art of the Asia Pacific region, 1917-1975. 113 1. Social realism in the Asia Pacific region 114 2. Socialist Realism in the Asia Pacific region 1. Russia and China: (a) Socialist in content 121 Russia and China: (b) Realist in style 131 2.