Intellectual Property Forum Issue 123

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julian Burnside's Errors

_8462 SIQ 42 Vol 21:qxd8 17/09/13 11:04 AM Page 1 ISSUE 42 AUGUST 2013 ANNE HENDERSON – Learning from Calvin Coolidge STEPHEN MATCHETT on Lincoln’s White House, democracy and power at play ROSS FITZGERALD reviews books on Bill Woodfull, Old Xaverians Football Club, Footy Town and Madeleine St John Jim Griffin, Daniel Mannix & the ABD ANONYMOUS, a study on the American firearm Asylum Seekers and the Confusion of DAVID MARR & JULIAN BURNSIDE LINDA MOTTRAM & EMMA ALBERICI in the Conservative-Free-Zone MEDIA WATCH’S Sandalista Watch with the ABC’s “Whitlam: the Lyrical” Published by The Sydney Institute 41 Phillip St. with Gerard Henderson’s Sydney 2000 Ph: (02) 9252 3366 MEDIA WATCH Fax: (02) 9252 3360 _8462 SIQ 42 Vol 21:qxd8 17/09/13 11:04 AM Page 2 The Sydney Institute Quarterly Issue 42, August 2013 l CONTENTS LINDA MOTTRAM & EMMA ALBERICI REFLECT Editorial 2 ABC CONSENSUS ABC managing director and editor-in-chief Mark Scott Why the 1920s “Roared” - likes to present himself as a vibrant media manager with Calvin Coolidge and Debt a business plan that works. This glosses over the reality a that the ABC’s business plan involves travelling to - Anne Henderson 3 Canberra with an empty case and having it loaded up with taxpayers’ funds by an obliging government. A Study on the American Firearm Despite the current financial constraints, Mark Scott - Anonymous 7 managed to receive an extra $90 million for the ABC in this year’s budget. Some funds will be spent on a Fact i Checking Unit, which will ignore errors in ABC Book Reviews programs but will focus on the alleged errors made by - Ross Fitzgerald 11 business, political parties and other organisations. -

Justice Jottings

Australian Society of Presentation Sisters Spring 2014 Volume 7, Issue 3 Justice Jottings We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land on which we live. We acknowledge their deep spiritual connections to this land and we thank them for the care they have shown to Earth over thousands of years. Inside this issue: The Moses in my heart trembles, She hears God’s challenge: not quite willing to accept the prophet The ground of your being is holy. G20 and the Cries hidden in my being, Take off your shoes! of the Vulnerable 1 wondering how much it will cost Awaken your sleeping prophet. to allow the prophet to emerge. Believe in your Moses and go. Sydney Peace Prize 1 In these lines, Macrina Wiederkehr This edition shows some of today’s prophets acting captures the reluctance experienced by on their beliefs with compassion and courage. Justice Contacts’ Anne Shay, Peta Anne Molloy Meeting 1 prophets across the centuries. The Cry of the Poor and the Cry of the The Lord hears the cries Earth 2-3 of the vulnerable Reconciliation: More Bridges to Cross 4 The G20 leaders and their staffs Much less media attention focused have left, the barricades have been on Christian groups who, during Fraser Island - removed. Political analysts have several months before the Summit, Native Title Rights 4 commented on the outcomes of this met and planned ways to alert the forum and rejoiced in the peaceful- wider community to the vulnerable ness of the street rallies. Many civil people who will be most affected by society groups tried to influence the Julian Burnside AO QC the G20 outcomes. -

Our Shared Passion for Music

Our Shared Passion for Music Philanthropy Impact Report 2018 —2019 Extending Music’s Extraordinary Impact Together Womenjika and welcome As we reach the coda of our landmark 10th Anniversary In 2018-19, more than 8,000 generous music lovers year, it’s wonderful to reflect on all that we have achieved joined you in making gifts of all types that have ensured to our 2018—2019 Philanthropy together over the past decade and offer our sincere the continued vibrancy of the musical, artist development Impact Report. thanks for your inspiring commitment to Melbourne and learning and access programs that form the core Recital Centre. Whether you have recently joined us, of our work here at the Centre. Your support also or have been a part of our generous community of played a crucial role in bringing to life several special supporters since we first opened our doors, your 10th Anniversary initiatives, including a suite of 10 new philanthropic gifts and sponsorship have enriched the music commissions, our $10 tickets access initiative for lives of so many people in our community; from first time attendees, and the purchase of a new Steinway musicians and seasoned concert-goers, to those Model C grand piano for the Primrose Potter Salon. who are discovering the joy of music for the first time. This past year also saw the launch of our new seat dedication program that provided 39 music lovers with a platform to express their deep connection to the Centre. We have come a long way in our first 10 years, and the firm footing you have helped us establish means that we now look forward to our second decade with Eda Ritchie AM Euan Murdoch Chair, Foundation CEO confidence and energy. -

SBF Overview

SECTION 02 Global Implementation of Mizu To Ikiru SBF Overview We are developing our five regional businesses by focusing on the needs of customers in each country and market. Number of employees Business overview Main products (as of December 31, 2018) Main company name (start year) Suntory Foods Limited (1972) We are strengthening the position of long-selling brands like Suntory Beverage Solution Limited (2016) Suntory Holdings Suntory Tennensui and BOSS, while offering a wide portfolio Suntory Beverage Service Limited (2013) that includes tea, juice drinks, and carbonated beverages. We JAPAN 9,682 Japan Beverage Holdings Inc. (2015) also develop integrated beverage services such as vending Suntory Foods Okinawa Limited (1997) machines, cup vending machines, and water dispensers. Suntory Products Limited (2009) Our business in Europe focuses on brands that have been Suntory Beverage & Food (SBF)* locally loved for many years. Alongside core brands like Orangina Schweppes Holding B.V. (2009) Orangina in France, and Lucozade and Ribena in the UK, EUROPE 3,798 Lucozade Ribena Suntory Limited (2014) we are also developing Schweppes carbonated beverages and a wide range of other products. Our business in Asia consists of soft drinks and health supplements. We have established joint venture companies Suntory Beverage & Food Asia Pte. Ltd. (2011) that manage the soft drink businesses in Vietnam, Thailand, BRAND’S SUNTORY INTERNATIONAL Co., Ltd. (2011) ASIA and Indonesia in a way that fits the specific needs of each 6,963 PT SUNTORY GARUDA BEVERAGE (2011) market. The health supplement business focuses on the Suntory PepsiCo Vietnam Beverage Co., Ltd. (2013) manufacture and sale of the nutritional drink, BRAND’S Suntory PepsiCo Beverage (Thailand) Co., Ltd. -

Volume 05 | 2017 the Age of Statutes Judicial College of Victoria Journal Volume 05 | 2017

Judicial College of Victoria Journal Volume 05 | 2017 The Age of Statutes Judicial College of Victoria Journal Volume 05 | 2017 Citation: This journal can be cited as (2017) 5 JCVJ. Guest Editor: The Hon Chief Justice Marilyn Warren AC ISSN: ISSN 2203-675X Published in Melbourne by the Judicial College of Victoria. About the Judicial College of Victoria Journal The Judicial College of Victoria Journal provides practitioners and the wider legal community with a glimpse into materials previously prepared for the Judicial College of Victoria as part of its ongoing role of providing judicial education. Papers published in this journal address issues that include substantive law, judicial skills and the interface between judges and society. This journal highlights common themes in modern judicial education, including the importance of peer learning, judicial independence and interdisciplinary approaches. Submissions and Contributions The Judicial College of Victoria Journal welcomes contributions which are aligned to the journal’s purpose of addressing current legal issues and the contemporary role of judicial education. Manuscripts should be sent electronically to the Judicial College of Victoria in Word format. The Judicial College of Victoria Journal uses the Australian Guide to Legal Citation: http://mulr.law.unimelb.edu.au/go/AGLC3. Disclaimer The views expressed in this journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Judicial College of Victoria and the Editor. While all care has been taken to ensure information is accurate, no liability is assumed by the Judicial College of Victoria and the Editor for any errors or omissions, or any consquences arising from the use of information contained in this journal. -

Valencia Niega Su Implicación En ‘Imelsa’ Betoret Ve Una «Venganza» De Benavent Las Acusaciones Sobre ‘Mordidas’ Que Podrían Propiciar Su Imputación

Dinero gratis del BCE para reactivar la economía europea El Banco Central Europeo reducirá el interés de referencia al 0% y ampliará de 60.000 a 80.000 millones al mes el programa de compra de deuda soberana, aunque los expertos dudan que la eurozona se ‘reanime’ con más medidas monetarias. El euríbor podría bajar, pero no se notarán grandes efectos a pie de calle. 2 VIERNES 11 de marzo de 2016 Año XVII. Número 3679 174.000 PERSONAS SIGUEN SIN PODER VOLVER A FUKUSHIMA Ecologistas alertan de que la zona contaminada seguirá inhabitable durante décadas. Hoy se cumplen 5 años del peor accidente nuclear desde Chernóbil. 5 EN PRIMERA PERSONA «LO QUE ESTÁN HACIENDO ES ‘BARRER’ 5 CM DE SUELO» KIMIMASA MAYAMA / EFE MAYAMA KIMIMASA El presidente del PP ĉ10 a 12 de Valencia niega su implicación en ‘Imelsa’ Betoret ve una «venganza» de Benavent las acusaciones sobre ‘mordidas’ que podrían propiciar su imputación. 6 La crisis está Crimen de Carrasco: obligando Monsterrat y Triana, 22 a exprostitutas y 20 años; Raquel Gago, a volver a la calle 4 5 por encubrimiento 4 JESÚS CARRASCO: «MI MIRADA ES AL EL VALENCIA CAE EN BILBAO CAMPO, Y SÉ QUE @CASTLESOFEUROPE ĉ VA A LA CONTRA» 8 y 9 (1-0), PERO PUDO SER PEOR LA CHAPUZA DEL ‘ECCE HOMO’ DE BORJA, EN VERSIÓN CASTILLO 4 ĉ| 2 | 20MINUTOS VIERNES, 11 DE MARZO DE 2016 ¼ºÓÓ Nueva víctima mortal de violencia machista en Valencia Una mujer de 51 años fa- lleció ayer en Catarroja (Valencia) presuntamente a manos de su pareja, que se entregó a la Guardia Ci- vil con heridas en la cara y extremidades y confesó el crimen, según informa- ron fuentes cercanas a la investigación. -

Vma Championships and Vrwc Races, Dolomore Oval, Mentone, Sunday 10 April 2011

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2010/2011 Number 28 11 April 2011 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours : Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au/ VMA CHAMPIONSHIPS AND VRWC RACES, DOLOMORE OVAL, MENTONE, SUNDAY 10 APRIL 2011 It was cool, overcast and intermittently windy at Mentone for the annual VMA 5000m track walk championships last Sunday morning but the rain held off and our walkers raced well. Kelly Ruddick 23:23 and Stuart Kollmorgen 22:13 won their respective races and there were a whole swag of walkers over the 80% Age Graded Performance mark. The best were Heather Carr with 92.66% (26:59 for W60) and Bob Gardiner 90.31% (29:36 for M75). It was great to see Tony Johnson back in walking mode and doing it in fine style to win the M70 with 30:41. We also welcomed Croatian walker Sasha Radotic, currently in Australia for next weekend's Coburg 24 Hour Run – he took third in the M40 division with 27:15. VMA 5000M CHAMPIONSHIPS – WOMEN W35 1 Ruddick, Kelly 37 23:23 86.19% W45 1 Shaw, Robyn 49 29:58 73.80% W50 1 Elms, Donna 50 32:02 69.65% W55 1 Thompson, Alison 58 29:25 82.14% W60 1 Carr, Heather 61 26:59 92.66% W60 2 Feldman, Liz 62 31:17 80.88% W60 3 Johnson, Celia 63 33:59 75.37% W65 1 Steed, Gwen 68 33:31 81.67% W70 1 Beaumont, Margaret 73 42:05 68.76% W75 1 Browning, Betty 79 45:06 67.67% W75 -

2018 World Masters Championships Women / August 17 - 25, 2018 Age Group W70 Weight Category 58 Body Snatch Clean & Jerk SMF T Name Nat

2018 World Masters Championships Women / August 17 - 25, 2018 Age Group W70 Weight Category 58 Body Snatch Clean & Jerk SMF T Name Nat. Wt. Age 1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd Total Total 1 HUUSKONEN Terttu FIN 54.62 74 29 31 32 39 41 42 73 216.410 2 MCSWAIN Dagmar AUT 57.35 74 23 25 25 28 30 31 55 157.680 Age Group W70 Weight Category 69 Body Snatch Clean & Jerk SMF T Name Nat. Wt. Age 1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd Total Total 1 DOLMAN Lynn GBR 66.72 70 25 26 27 30 32 34 61 144.320 Age Group W70 Weight Category 75 Body Snatch Clean & Jerk SMF T Name Nat. Wt. Age 1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd Total Total 1 QUINN Judy CAN 74.35 70 29 31 33 39 41 41 74 165.290 Age Group W65 Weight Category 48 Body Snatch Clean & Jerk SMF T Name Nat. Wt. Age 1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd Total Total 1 BOURGE Christine FRA 46.18 66 27 29 30 37 39 41 69 191.690 Age Group W65 Weight Category 53 Body Snatch Clean & Jerk SMF T Name Nat. Wt. Age 1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd Total Total 1 BERENDSEN Maria NED 51.42 67 33 35 35 39 41 41 74 193.360 2 DAVIS Julie AUS 51.76 66 26 27 28 35 37 39 65 165.220 3 MATSUZAKI Junko AUS 52.18 69 23 24 25 40 41 42 65 176.230 Age Group W65 Weight Category 58 Body Snatch Clean & Jerk SMF T Name Nat. -

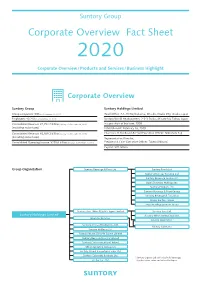

Corporate Overview Fact Sheet 2020

Suntory Group Corporate Overview Fact Sheet 2020 Corporate Overview/ Products and Services / Business Highlight Corporate Overview Suntory Group Suntory Holdings Limited Group companies: 300 (as of December 31, 2019) Head Office: 2-1-40 Dojimahama, Kita-ku, Osaka City, Osaka, Japan Employees: 40,210 (as of December 31, 2019) Suntory World Headquarters: 2-3-3 Daiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan Consolidated Revenue: ¥2,294.7 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) Inauguration of business: 1899 (excluding excise taxes) Establishment: February 16, 2009 Consolidated Revenue: ¥2,569.2 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) Chairman of the Board & Chief Executive Officer: Nobutada Saji (including excise taxes) Representative Director, Consolidated Operating Income: ¥259.6 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) President & Chief Executive Officer: Takeshi Niinami Capital: ¥70 billion Group Organization Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd. Suntory Foods Ltd. Suntory Beverage Solution Ltd. Suntory Beverage Service Ltd. Japan Beverage Holdings Inc. Suntory Products Ltd. Suntory Beverage & Food Europe Suntory Beverage & Food Asia Frucor Suntory Group Pepsi Bottling Ventures Group Suntory Beer, Wine & Spirits Japan Limited Suntory Beer Ltd. Suntory Holdings Limited Suntory Wine International Ltd. Beam Suntory Inc. Suntory Liquors Ltd.* Suntory (China) Holding Co., Ltd. Suntory Spirits Ltd. Suntory Wellness Ltd. Suntory MONOZUKURI Expert Limited Suntory Business Systems Limited Suntory Communications Limited Other operating companies Suntory Global Innovation Center Ltd. Suntory Corporate Business Ltd. * Suntory Liquors Ltd. sells alcoholic beverage Sunlive Co., Ltd. (spirits, beers, wine and others) in Japan. Suntory Group Corporate Overview Fact Sheet Products and Services Non-alcoholic Beverage and Food Business/Alcoholic Beverage Business Non-alcoholic Beverage and Food Business We deliver a wide range of products including mineral water, coffee, tea, carbonated drinks, sports drinks and health foods. -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

Summary of Consolidated Financial Results for the Fiscal Year Ended

English Translation February 14, 2019 Summary of Consolidated Financial Results for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2018 <IFRS> (UNAUDITED) Company name: Suntory Beverage & Food Limited Shares listed: First Section, Tokyo Stock Exchange Securities code: 2587 URL: https://www.suntory.com/sbf/ Representative: Saburo Kogo, President and Chief Executive Officer Inquiries: Yuji Yamazaki, Director, Senior Managing Executive Officer, Division COO, Corporate Strategy Division TEL: +81-3-3275-7022 (from overseas) Scheduled date of ordinary general meeting of shareholders: March 28, 2019 Scheduled date to file securities report: March 29, 2019 Scheduled date to commence dividend payments: March 29, 2019 Preparation of supplementary material on financial results: Yes Holding of financial results presentation meeting (for institutional investors and analysts): Yes (Millions of yen with fractional amounts discarded, unless otherwise noted) 1. Consolidated financial results for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 (from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018) (1) Consolidated operating results (Percentages indicate year-on-year changes) Revenue Operating income Profit before tax Profit for the year Fiscal year ended (Millions of yen) (%) (Millions of yen) (%) (Millions of yen) (%) (Millions of yen) (%) December 31, 2018 1,294,256 4.9 113,557 (3.7) 111,813 (2.3) 88,833 3.1 December 31, 2017 1,234,008 2.1 117,955 5.4 114,442 6.2 86,175 9.7 Profit for the year Comprehensive income attributable to owners of for the year the Company Fiscal year ended -

Former CJ Spigelman Appointed to HK Court of Final Appeal FINAL

Issued 9 April 2013 Former NSW Chief Justice appointed to Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal Former NSW Chief Justice James Spigelman has been appointed to the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. The appointment was announced yesterday in Hong Kong, jointly by the court’s Chief Justice, Mr Geoffrey Ma Tao-li, and the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, Mr C Y Leung. The Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal is the highest appellate court in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Established in 1997, it has the power of final adjudication with respect to the civil and criminal laws of Hong Kong. It comprises permanent Hong Kong judges, non-permanent Hong Kong judges and non- permanent common law judges from other jurisdictions. The Honourable Mr Justice Spigelman has been appointed a non-permanent judge from another common law jurisdiction. He will sit on appeals for a period of time each 12 to 18 months. He joins other distinguished Australian jurists previously appointed including three former Chief Justices of Australia, Sir Anthony Mason, Sir Gerard Brennan and Murray Gleeson, and, also announced yesterday, Justice William Gummow. The Honourable Mr Justice Spigelman was appointed NSW Chief Justice in May 1998 and served until May 2011. He is currently Chair of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (since April 2012). NSW Chief Justice Tom Bathurst congratulated his predecessor on this most recent appointment. "In addition to his significant contribution to the law in this state and country, Mr Spigelman was responsible for engaging with our legal colleagues throughout the Asian region in a way that had never been done before," Chief Justice Bathurst said.