“I Will Let My Art Speak Out”: Visual Narrations of Youth Combating Intolerance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Say Yes to the Text

Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, Vol. 5, No.1/2, 2015, pp. 42-49. Say Yes to the Text Jennifer Burg In this essay, the author describes her experience as a participant in the reality television show Say Yes to the Dress. She delves into the production aspects of the show and her own feelings of identification with the production staff. She also considers the multiple audiences, both present and not present, in applying for, producing, and par- ticipating in a reality television show. Keywords: Audience, Autoethnography, Bridal Rituals, Femininity, Reality Television, Wedding Rituals Proposal For years when we were single, my best friend Jackie and I would come home from late nights out in NYC, climb into her bed with bowls of cereal, and watch TV until we fell asleep. Our fa- vorites were shows that aired on TLC, and of those we most loved Say Yes to the Dress. We took great pleasure in watching the brides-to-be try on, reject and select their dream dresses in the sparkly showroom of Kleinfeld, in the heart of Manhattan. We critiqued every ensemble, mar- veled at every price point, and added our own snarky commentary to that of the friends and fami- ly who came along to assist the soon-to-be-wed. We scrutinized everything from the tiaras to the toe clips and the whole lot in between. We had our favorite designers, and we knew the Kleinfeld consultants by name. Never did we think that we might actually have the experience that we so often watched: Jackie has two kids and is divorced; I was engaged once years ago, but that didn’t work out. -

Wiarnon How Do You Cook Leg of Lamb?

A A. PAGE TWENTY-F0UR\ i ' THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 1969 ■ N ilanirlTPBtrr lEtiming fcralii ^ AviNage Dsily Net Press Run 9 m The W e e k M M Thp Weather VFW Auxiliary will hold a An open house will be held for A m 38, U M Cloudy with chance of drizzle About Town rummage sale next Wednesday Mi^ and Mrs. Thomas Albro, GOP Lead 35 Weiss Teaches at the poet home. Members may through Saturday noon. Low to formerly of 80 Winter St., on St. Bridget R o s a ^ Society bring articles for sAle to the Manchester • Democrats Course at MCC a s , 4 5 9 night in _the 60s. ’Tom onow’s will have its annual installation meeting Tuesday. Those wish Sunday from 2:30 to 8 p.m., at continue to cut Into the R e high in the 7Da. 'v Town Manager Robert Weiss banquet Sept. 16 , at 6:30 p.m. ing to have articles picked up tlve home of their daughter and publican lead in registered,, Manehemter— A City of Pillage Charm started teaching a class la.t at W illie’s Steak House. Reser may call Mrs. Florence Plltt of son-ln-Iaw, Mr. and MrSj_ Jack voters, and the GOP margin, 816 Main St. night at Manchester Community VOL. LXXXVm. NO. 286 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) vations will close Monday. The Krafjack, . 100 Meadow Lark as of today,; is dofVn to 35, How do You MANCHESTER, OONN, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 1969 / (C A M e m e M s m P li«e M ) College, and will conduct the PRICE TEN CENTS Rev. -

Observations About Leadership, Service, and Being a Human at Work

observations about leadership, service, and being a human at work FOREW0RD When Geoff asked me to write this, I accepted with delight and then immediately Googled “how to write a foreword.” The internet told me that it’s my job to introduce his work to the world, which seems like an awfully big responsibility. Geoff and I are unconventional friends, though, so I think it fitting that my contribution here sidesteps tradition a bit. I possess absolutely no authority that qualifies me to introduce the actual content of this book, so I won’t insult your intelligence by pretending I do. What I will do, with absolute confidence, is endorse its author. I could go on for an annoyingly long time about the kind of person he is, listing the many reasons I find him extraordinary until I’ve exhausted both you and all the known English superlatives. Instead of that, I’m going to tell you the most important thing you need to know about him before you start reading. Geoff is the most genuine person I’ve ever met. He passionately means every word you’re about to read and the tenets of his work are principles by which he actively lives. You’ll see some good examples of that throughout these pages, but I’m here to assure you that none of it is lip service – it’s legit. I’m lucky enough to get to witness it daily, so I could definitely tell you if he was faking. He’s not. I can’t guarantee that reading this will change your life as much as knowing Geoff has changed mine, but it’s a damn good place to start. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Desperate Housewives

Desperate Housewives Titre original Desperate Housewives Autres titres francophones Beautés désespérées Genre Comédie dramatique Créateur(s) Marc Cherry Musique Steve Jablonsky, Danny Elfman (2 épisodes) Pays d’origine États-Unis Chaîne d’origine ABC Nombre de saisons 5 Nombre d’épisodes 108 Durée 42 minutes Diffusion d’origine 3 octobre 2004 – en production (arrêt prévu en 2013)1 Desperate Housewives ou Beautés désespérées2 (Desperate Housewives en version originale) est un feuilleton télévisé américain créé par Charles Pratt Jr. et Marc Cherry et diffusé depuis le 3 octobre 2004 sur le réseau ABC. En Europe, le feuilleton est diffusé depuis le 8 septembre 2005 sur Canal+ (France), le 19 mai sur TSR1 (Suisse) et le 23 mai 2006 sur M6. En Belgique, la première saison a été diffusée à partir de novembre 2005 sur RTL-TVI puis BeTV a repris la série en proposant les épisodes inédits en avant-première (et avec quelques mois d'avance sur RTL-TVI saison 2, premier épisode le 12 novembre 2006). Depuis, les diffusions se suivent sur chaque chaîne francophone, (cf chaque saison pour voir les différentes diffusions : Liste des épisodes de Desperate Housewives). 1 Desperate Housewives jusqu'en 2013 ! 2La traduction littérale aurait pu être Ménagères désespérées ou littéralement Épouses au foyer désespérées. Synopsis Ce feuilleton met en scène le quotidien mouvementé de plusieurs femmes (parfois gagnées par le bovarysme). Susan Mayer, Lynette Scavo, Bree Van De Kamp, Gabrielle Solis, Edie Britt et depuis la Saison 4, Katherine Mayfair vivent dans la même ville Fairview, dans la rue Wisteria Lane. À travers le nom de cette ville se dégage le stéréotype parfaitement reconnaissable des banlieues proprettes des grandes villes américaines (celles des quartiers résidentiels des wasp ou de la middle class). -

The Bride in American Media: a Feminist Media Studies And

THE BRIDE IN AMERICAN MEDIA: A FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES AND CRITICAL ANALYSIS, 1831-2012 by EMILIA NOELLE BAK (Under the Direction of Janice Hume) ABSTRACT This dissertation examined the figure of the bride in American media. Today, the bride is a ubiquitous figure. She graces the covers of magazines, websites are devoted to her, and multiple television series star her. This study aimed to understand the American bride contemporarily and historically by examining magazine media from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as well as today’s reality television programming. Pulling from feminist media studies and critical cultural studies and proceeding from the standpoint that representations matter, portrayals of the bride were analyzed in terms of gender, class and race for ways in which these representations affirmed and/or resisted the dominant ideology. The bride was examined in media targeted at women to understand how media meant for women talked about the bride, a uniquely female figure. The nineteenth-century women’s magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book, the twentieth-century women’s magazine Ladies’ Home Journal and today’s most notorious reality bride show, Bridezillas, were all examined. INDEX WORDS: bride, Godey’s Lady’s Book, Ladies’ Home Journal, Bridezillas, feminist media studies, cultural studies, wedding THE BRIDE IN AMERICAN MEDIA: A FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES AND CRITICAL ANALYSIS, 1831-2012 by EMILIA NOELLE BAK AB, University of Georgia, 2007 MA, University of Georgia, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The -

[email protected] Hometown of P a S C a G O U L a , Miss

THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF MERCYHURST COLLEGE SINCE 1929 ARTS& ~LAKER ENTERTAINMENT Jimmy Carter accepts Nobel Peace Prize SPORTS StarTrek : Nemsis' boldly Men's Basketball pounds goes . Nowhere Page 2 Point Park 102-68 PAGE 9 PAGE 12 Vol. B B S 10 H^^^^^Hffi^B wtm m HSBWH HBafi wmmmimm m mm ^ Happy Chanukah What signals are you sending? MSG lecture on sex signals brings awareness to students # *6&it By Kelly Rose Duttine News Editor More than 250 Mercyhurst students packed into the Dr. Barrett and Catherine Walker Recital Hall in the new Hirt Academic Center t o talk about sex. G wen Druyor and Christian Murphy from Bass/Schuler Entertainment presented a 90 minute long presentation on Dec. 12 as part of Mercyhurst Happy Kwanza Student Government's 2002** 2003 Lecture Series. The dynamic pair presented a lively and energetic lecture about the sex signals we send and receive from others. The presentation included stereo- types about what typical men and women want, sexual in- nuendoes, and reversed roles in relationships. Druyor and JodyM- :od photographer Murphy used many funny KWANZAA pickup lines, jokes, and skits JodyM that took place at typical bar w/iwiwjiiwv'av 1 Gwen Druyor and Christian Murphy get "friendly" during MSG's lecture "Sex Signals' receives positive audience and party scenes, familiar to feedback. Please see signals on page 3on e of their skits. Merry Christmas MNE going after $1 t o $2 Students receive awards millionfederal grant Community service and dedication honored at open reception By Scott Mackar // wasn 't like this Assistant news editor 44 By Kristin Purdy Being the third year for this rec- "I got an invitation [to the re- grant came out of the sky, Editor-in-Chief ognition ceremony, the criteria for ception] in the mail and I was Mercyhurst North East received we had to work really hard eligible students is wide, yet in- surprised. -

Jason Weeks Song List

High Energy A-Ha- Take on me Amy Winehouse- Valerie Beach Boys- Wouldn’t it be nice Beatles- I feel fine Blink 182- What’s my age again Blink 182- All the small things Blink 182- Dammit Coldplay- Viva la vida CCR- Proud Mary The Cure- Friday I’m in love Del Amitri- Roll to me Dion- Runaround Sue Eagles- Take it easy Eagles- Hotel CA Foo Fighters- Learn to fly Garth Brooks- Friends in low places Gin Blossoms- Hey Jealousy Gin Blossoms- Follow you down Goo Goo Dolls- Slide Green Day- When I come around Green Day- Basket case Jackson Browne- Somebody’s baby Jimmy Eat World- The middle Jimmy Eat World- Sweetness John Mayer Trio- Who did you think I was Killers- Mr. Brightside Lit- Own worst enemy Modern English- Melt with you Notorious B.I.G.- Big poppa Rihanna- Umbrella The Outfield- Your love Tal Bachman- She’s so high Third Eye Blind- Jumper Third Eye Blind- Never let you go Tom Petty- American girl Tom Petty- Break down Tom Petty- Mary Jane Tonic- If you could only see Van Morrison- Brown eyed girl Weezer- Surf wax america Wheatus- Teenage dirtbag Yellowcard- Ocean Ave Medium Energy Allen Stone- Brown eyed lover Beach Boys- God only knows Beatles- Norwegian Wood Beatles- Hey Jude Beatles- Across the universe Blink 182- I miss you medley Brooks and Dunn- Neon moon Chris Stapleton- Tennessee whiskey Dashboard confessional- Vindicated DMB- Crash into me Fleetwood Mac- Dreams Fleetwood Mac- Everywhere Fleetwood Mac- Never going back again Foo Fighters- My Hero Foo Fighters- Everlong Fuel- Shimmer Green Day- Good Riddance Green Day- Macy’s Day -

An Interview with C. Brett Bode Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission

An Interview with C. Brett Bode Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission C. Brett Bode was in private practice and was an assistant city attorney for East Peoria, from 1968-70, and then was a public defender in Tazewell County from 1970-72 while also maintaining a private practice. In 1972 he was elected State’s Attorney of Tazewell County and served in that position until 1976, when he returned to private practice. Bode also served as a public defender in Tazewell County after he was State’s Attorney from 1976-82. He became an Associate Judge in the Tenth Judicial Circuit in 1982 and served in that position until his retirement in 1999. Interview Dates: April 2nd, 2015; October 23rd, 2015; and December 15th, 2015 Interview Location: Judge Bode’s home, Pekin, Illinois Interview Format: Video Interviewer: Justin Law, Oral Historian, Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission Technical Assistance: Matt Burns, Director of Administration, Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission Transcription: Interviews One and Two: Benjamin Belzer, Research Associate/Collections Manager, Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission Interview Three: Audio Transcription Center, Boston Massachusetts Editing: Justin Law, and Judge Bode Total pages: Interview One, 65; Interview Two, 57; Interview Three, 60 Total time: Interview One, 02:49:07; Interview Two, 02:26:37; Interview Three, 02:48:38 1 Abstract C. Brett Bode Biographical: Carlton Brett Bode was born in Evanston, Illinois on July 9th, 1939, and spent his early life in Irving Park, Illinois and teenage years in Fox River Grove, Illinois. Graduating from Crystal Lake High School in 1957 he joined the Marine Corps and became a helicopter pilot. -

曲名 アルバム アーティスト 再生日時 Who Did You Think I Was? Try

曲名 アルバム アーティスト 再生日時 出発 Who Did You Think I Was? Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 3:45 Good Love Is On The Way Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 x:xx Wait Until Tomorrow Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 x:xx Gravity Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 x:xx Vultures Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 x:xx Out Of My Mind Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 x:xx Another Kind Of Green Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 x:xx I Got A Woman Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 4:24 Something's Missing Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 4:31 Daughters Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 4:37 Try Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 4:44 Who Did You Think I Was? Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 4:47 Good Love Is On The Way Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 4:52 Wait Until Tomorrow Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 4:56 Gravity Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 5:02 Vultures Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 5:07 Out Of My Mind Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 5:15 Another Kind Of Green Try! John Mayer Trio 06/08/13 5:19 双葉SA@中央道 Beat It Upright Untouchables KORN 06/08/13 6:01 The Deathless Horsie You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore, Vol. 1 Frank Zappa 06/08/13 6:06 Bad Case Of Loving You (Doctor Doctor) Some Guys Have All The Luck Robert Palmer 06/08/13 6:09 Keep on Pushing A Tribute to Curtis Mayfield Tevin Campbell 06/08/13 6:13 midnight peepin' BARBEE BOYS BARBEE BOYS 06/08/13 6:17 しようよ (Let's do it) 007 Gold Singer SMAP 06/08/13 6:22 Little Blue River LIVE The Bears 06/08/13 6:26 The Ring (Hypnotic Seduction of Dale) Flash Gordon Queen 06/08/13 6:27 So What Jeff Jeff Beck 06/08/13 6:31 And You And I Close To The Edge Yes -

COMPARE BUY Imagine Paying 10%, 20%, Or 25% Per Month on Short Term Loans

FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 4, 2017 3:09:00 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of March 12 - 18, 2017 Right and wrong Felicity Huffman stars in “American Crime” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 The anthology crime drama created by “12 Years a Slave” (2013) writer John Ridley may not be a ratings beast, but “American Crime” has garnered much critical acclaim for its raw portrayal of difficult subjects. Season 3 puts a spotlight on American labor issues and exploitation, with Felicity Huffman (“Desperate Housewives”), Regina King (“Ray,” 2004) and the rest of the core cast falling admirably into their new roles. The new season of “American Crime” premieres Sunday, March 12, on ABC. WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS COMPARE BUY Imagine paying 10%, 20%, or 25% per month on short term loans. Sounds absurd! Well, people do at pawn shops all the time. Mass pawn shops charge 10% per month SELL WINTER ALLERGIES plus fees. NH Pawn shops charge 20% and more. Example: A $1,000 short term loan TRADE ARE HERE! means you pay back $1,400-$1,800 depending on where you do business. Bay 4 DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN PARTS & ACCESSORIES Group Page Shell SALES & SERVICE We at CASH FOR GOLD SALEM, NH charge Motorsports Alleviate your mold allergies this season. 5 x 3” MASS. 0% interest. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” Call or schedule your appointment INSPECTIONS online with New England Allergy today. THAT’S RIGHT! NO INTEREST for the same 4 months Borrow $1000 - Pay back $1000. -

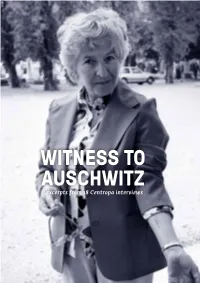

WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews

WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ excerpts from 18 Centropa interviews WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews As the most notorious death camp set up by the Nazis, the name Auschwitz is synonymous with fear, horror, and genocide. The camp was established in 1940 in the suburbs of Oswiecim, in German-occupied Poland, and later named Auschwitz by the Germans. Originally intended to be a concentration camp for Poles, by 1942 Auschwitz had a second function as the largest Nazi death camp and the main center for the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. Auschwitz was made up of over 40 camps and sub-camps, with three main sec- tions. The first main camp, Auschwitz I, was built around pre-war military bar- racks, and held between 15,000 and 20,000 prisoners at any time. Birkenau – also referred to as Auschwitz II – was the largest camp, holding over 90,000 prisoners and containing most of the infrastructure required for the mass murder of the Jewish prisoners. 90 percent of Auschwitz’s victims died at Birkenau, including the majority of the camp’s 75,000 Polish victims. Of those that were killed in Birkenau, nine out of ten of them were Jews. The SS also set up sub-camps designed to exploit the prisoners of Auschwitz for slave labor. The largest of these was Buna-Monowitz, which was established in 1942 on the premises of a synthetic rubber factory. It was later designated the headquarters and administrative center for all of Auschwitz’s sub-camps, and re-named Auschwitz III. All the camps were isolated from the outside world and surrounded by elec- trified barbed wire.