A Study of Psychological Reverberations in Walker Percy's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 “AMERICA on a SHELF” COLLECTION 101 American

“AMERICA ON A SHELF” COLLECTION 101 American Customs : Understanding Language and Culture Through Common Practices [Paperback] Harry Collis (Author) Publisher: McGraw-Hill; 1 edition (October 1, 1999) The Accidental Tourist: A Novel By Anne Tyler (Ballantine Reader's Circle) Across The River and Into the Trees Ernest Hemingway; Paperback The Adventures of Augie March (Penguin Classics) Saul Bellow; Paperback After This by Alice McDermott (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) Age of Innocence By Edith Wharton Al Capone and His American Boys: Memoirs of a Mobster's Wife William J. Helmer (Editor) Publisher: Indiana University Press (July 7, 2011) America The Story of Us: An Illustrated History [Paperback] Kevin Baker (Author), Prof. Gail Buckland (Photographer), Barack Obama (Introduction) Publisher: History (September 21, 2010) American Civilization: An Introduction [Paperback] David C. Mauk (Author), John Oakland (Author) Publisher: Routledge; 5 edition (August 16, 2009) The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation [Paperback] Jim Cullen (Author) Publisher: Oxford University Press, USA (June 14, 2004) American English: Dialects and Variation (Language in Society) [Paperback] Walt Wolfram (Author) Publisher: Wiley-Blackwell; 2nd Edition edition (September 12, 2005) American Values - Opposing Viewpoints Series Author David M. Haugen Publisher: Greenhaven (November 7, 2008) 1 American Ways: A Cultural Guide to the United States Gary Althen (Author) Publisher: Nicholas Brealey Publishing; 3 edition (February 16, 2011) American -

A Too-Brief, Incomplete, Unalphabetized List of Must-Read

A Too-Brief, Incomplete, Unalphabetized List of Must-Read that You Might Not Have Been Taught or Otherwise Made to Read Novels and Short Story Collections Written in the 20th and 21st Centuries Saul Bellow: Henderson the Rain King, Humboldt’s Gift, The Adventures of Augie March, Herzog Grace Paley: Collected Stories Flannery O’Conner: Collected Stories (especially the story from A Good Man is Hard to Find) Evan Connell: Mrs. Bridge, Mr. Bridge Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita, Pale Fire Ralph Ellison: Invisible Man Mary McCarthy: The Group, The Company She Keeps Nathanael West: Miss Lonelyhearts, The Day of the Locust Eudora Welty: Collected Stories Tess Slesinger: The Unpossessed Dagoberto Gilb: The Last Known Residence of Mickey Acuna Don DeLillo: End Zone, White Noise, Underworld Cormac McCarthy: Suttree, All the Pretty Horses, The Road, Blood Meridian Muriel Spark: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Memento Mori, The Comforters, Aiding and Abetting Kazuo Ishiguro: Never Let Me Go, The Unconsoled Zora Neale Hurston: Their Eyes Were Watching God Donald Barthelme: Sixty Stories, Forty Stories Thomas Pynchon: V, Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow Padgett Powell: Edisto, Edisto Revisited, Aliens of Affection Barry Hannah: Airships Steven Millhauser: Edwin Mullhouse, Martin Dressler Colson Whitehead, The Intuitionist Heidi Julavits: The Effects of Looking Backwards John Cheever: The Stories of John Cheever, The Wapshot Chronicle Judy Budnitz: Nice Big American Baby, Flying Leap Lee K. Abbott: Love is the Crooked Thing Angela Carter: The Company of -

Q.) the Journal of John Winthrop Is Also Known As the History of New America

Q.) The journal of John Winthrop is also known as The History of New America. A.) False Q.) Benjamin Franklin is known as the First American. A.) True Q.) Thomas Cook authored the United States Declaration of Independence. A.) False Q.) Charlotte Temple was originally published under the title Charlotte, A True Tale. A.) False Q.) Uncle Tom's Cabin is an anti-slavery novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe. A.) True Q.) Wieland is considered the first American gothic novel. A.) True Q.) The author of the famous short stories, Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is Washington Irving. A.) True Q.) The Leatherstocking Tales series contains six novels. A.) False Q.) The Valley of Utah is the first fiction of Virginia colonial life. A.) False Q.) Richard Henry Dana exclaimed about the poem Thanatopsis, "That was never written on this side of the water!" A.) True Q.) Edgar Allan Poe referred to followers of the Transcendental movement as Fish-Pondians. A.) False Q.) George Washington Harris is the creator of the character Sut Lovingood. A.) True Q.) Dennis Wendell Holmes, Sr. coined the term 'Brahmin Caste of New England.' A.) False Q.) Ralph Waldo Emerson delivered the famous Phi Beta Kappa address 'The American Scholar.' A.) True Q.) Henry David Thoreau penned the essay Civil Obedience. A.) False Q.) Mark Twain called The Scarlet Letter a "perfect work of the American imagination." A.) False Q.) Nathaniel Hawthorne's fiction had a profound impact on Herman Melville. A.) True Q.) H.W. Longfellow was the first American to translate Divine Comedy. -

Changing Patterns of Southern Lady's Influence from the Old to the Contemporary South in Ellen Glasgow's and Walker Percy'

ROCZNIKI HUMANISTYCZNE Tom LIV-LV, zeszyt 5 – 2006-2007 URSZULA NIEWIADOMSKA-FLIS * CHANGING PATTERNS OF SOUTHERN LADY’S INFLUENCE FROM THE OLD TO THE CONTEMPORARY SOUTH IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S AND WALKER PERCY’S ŒUVRE In the antebellum times patriarchs believed that the Southern lady defined the image of the South itself, as she was inseparable from her background (GLASGOW, A Certain Measure, 82). The myth of the Southern lady, in- vented and sanctioned by Southern gentlemen, created an image of an aristo- cratic, pure, loving, and submissive lady. Her apparent duty was to play an ornamental role in her husband’s house; however, in a larger perspective, her maternal devotion and moral uprightness were to guarantee perpetration of white hegemony. Southern patriarchs did not want to waste all the virtues which they had been ascribing to their women through the myth of the Southern lady; there- fore, in order to create a practical reason for upholding the myth, they attrib- uted mysterious power and great significance to her demeanor — to her influence on a husband, family and society in general. The mythical image of woman as an innocent and inferior creature was enriched by her miraculous power to wield influence upon those less perfect around her. However, this imposed myth forced ladies to choose the “right” behavior in spite of themselves, or of their desires and hopes, “the Southern woman, who had borne the heaviest burden of the old slavery and the new freedom, was valued, in sentiment, chiefly as an ornament to civilization, and as a restraining influence over the nature of man” (GLASGOW, A Certain Mea- sure, 97-98). -

Doctoral Reading List American Literature 1865-1965 FICTION

Doctoral Reading List American Literature 1865-1965 FICTION (Novels and Short Story Collections) Alcott, Louisa May. Little Women Anderson, Sherwood. Winesburg, Ohio Baldwin, James. Go Tell it on the Mountain Barnes, Djuna. Nightwood Barth, John. The Floating Opera Bellow, Saul. The Adventures of Augie March Cahan, Abraham. The Rise of David Levinsky Cather, Willa. My Antonia; The Professor’s House Chesnutt, Charles. The Marrow of Tradition Chopin, Kate. The Awakening Crane, Stephen. Maggie; The Red Badge of Courage DeBurton, Maria Amparo Ruiz. The Squatter and the Don Dos Passos, John. 1919 (from The USA Trilogy) Dreiser, Theodore. Sister Carrie Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury; As I Lay Dying Fauset, Jessie Redmon. There Is Confusion Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby Glasgow, Ellen. Barren Ground Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins. Iola Leroy Heller, Joseph. Catch-22 Hemingway, Ernest. In Our Time; The Sun Also Rises Howells, William Dean. The Rise of Silas Lapham Hurston, Zora Neale. Their Eyes Were Watching God James, Henry. The Portrait of a Lady; Daisy Miller; The Golden Bowl Jewett, Sarah Orne. The Country of the Pointed Firs Kerouac, Jack. On the Road Kesey, Ken. One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest Larsen, Nella. Passing Lewis, Sinclair. Main Street Marshall, Paule. Brown Girl, Brownstones Nabokov, Vladimir. Lolita Norris, Frank. The Octopus O’Connor, Flannery. A Good Man Is Hard To Find: 10 Memorable Stories Paredes, Americo. George Washington Gomez Percy, Walker. The Moviegoer Petry, Ann. The Street Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye Stein, Gertrude. Three Lives Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath Toomer, Jean. -

Comedy of Redemption in Three Southern Writers. Carolyn Patricia Gardner Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Comedy of Redemption in Three Southern Writers. Carolyn Patricia Gardner Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Gardner, Carolyn Patricia, "Comedy of Redemption in Three Southern Writers." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5796. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5796 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Storytelling and Existential Despair in Walker Percy's 'The Moviegoer'

Recovering the Creature: Storytelling and Existential Despair in Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer Ari N. Schulman [email protected] Submitted in partial requirement for Special Honors in the Department of English The University of Texas at Austin May 2009 Professor James Garrison Department of English Supervising Faculty Professor Coleman Hutchison Department of English Second Reader “The effort to understand the universe is one of the very few things that lifts human life a little above the level of farce, and gives it some of the grace of tragedy.” Steven Weinberg, epilogue to The First Three Minutes “What follows is a work of the imagination.” Walker Percy, preface to The Moviegoer TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. “The Essential Loneliness of Man” 9 2. The Loss of the Creature 19 3. The Fourth Man 34 4. The Singularities of Time And Place 57 5. Recovering the Creature 86 Bibliography 103 Schulman 1 Introduction In 1954, seven years before his first novel, The Moviegoer , was published and won the National Book Award, Walker Percy penned a stunning essay on modern man’s experience of alienation. The topic itself was hardly novel at the time. A cottage industry of cultural commentators was bemoaning the conformity and false optimism of the era, suggesting that beneath it lay a deep discontent. Holden Caulfield had been rallying angst-ridden teens against the phonies for three years. And the existentialists Camus and Sartre had long before argued that, worse than simply concealing some discontent, this rampant phoniness was really a means of denying the truth that life is absurd and meaningless. -

Sartrean Reading of American Novelist Walker Percy's The

Intercultural Communication Studies XXI: 2 (2012) Z. WANG Undefined Man: Sartrean Reading of American Novelist Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer Zhenping WANG Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Abstract: This paper is an exploration of the cross-cultural influence of Jean-Paul Sartre on Walker Percy, through a detailed analysis of the novel The Moviegoer. Jean-Paul Sartre was a twentieth century French existentialist philosopher whose theory of existential freedom is regarded as a positive thought that provides human beings infinite possibilities to hope and to create. It is specifically significant when the world is facing global crisis in economics, politics, and human behavior. The Moviegoer was the first novel by Walker Percy, one of the few philosophical novelists in America, who was very much influenced by Jean-Paul Sartre. Binx Bolling, the existentialist hero in the novel, must decide how to live his life in this world. He does not feel comfortable when Aunt Emily makes family stories to transfigure him, and when she preaches Stoicism as instructions in how to become a man. As an intentional consciousness, he feels he loses all the ability to think and to act. He starts a metaphysical search hinted by a new way of looking at the world around him to transcend “everydayness.” The paper is an attempt to apply Sartre’s theory of existential freedom as an approach to see how Binx resists, falls into, and resists again Aunt Emily’s tricks and traps of confinement and becomes a man undefined. Keywords: Being-in-itself, being-for-itself, being-for-others, existential freedom, undefined 1. -

Viewing of Authors Such As William

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 The Dislocation of Man in the Modern Age: The Pilgrim Condition and Mid-Twentieth Century American Catholic Literature Thomas Bevilacqua Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES “THE DISLOCATION OF MAN IN THE MODERN AGE”: THE PILGRIM CONDITION AND MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN CATHOLIC LITERATURE By THOMAS BEVILACQUA A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thomas Bevilacqua defended this dissertation on April 16, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Timothy Parrish Professor Co-Directing Dissertation S.E. Gontarski Professor Co-Directing Dissertation Martin Kavka University Representative Andrew Epstein Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of numerous people. First and foremost, I wish to thank my dissertation director, Timothy Parrish. One could not ask for a better dissertation director and I am forever grateful for his encouragement and guidance throughout this project. I would also like to thank S.E. Gontarski, not only being a thoughtful committee member but also for assuming dissertation co-director duties. I also wish to thank Andrew Epstein, Christina Parker-Flynn, and Martin Kavka for serving on my dissertation committee and providing helpful insights and assistance throughout this process. -

Msu Mfa Fiction Reading List 1

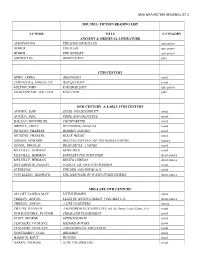

MSU MFA FICTION READING LIST 1 MSU MFA: FICTION READING LIST AUTHOR TITLE CATEGORY ANCIENT & MEDIEVAL LITERATURE ANONYMOUS THE SONG OF ROLAND epic poem HOMER THE ILIAD epic poem HOMER THE ODYSSEY epic poem SOPHOCLES OEDIPUS REX play 17TH CENTURY BEHN, APHRA OROONOKO novel CERVANTES, MIGUEL DE DON QUIXOTE novel MILTON, JOHN PARADISE LOST epic poem SHAKESPEARE, WILLIAM KING LEAR play 18TH CENTURY & EARLY 19TH CENTURY AUSTEN, JANE SENSE AND SENSIBILITY novel AUSTEN, JANE PRIDE AND PREJUDICE novel BALZAC, HONORE DE. COUSIN BETTE novel BRONTE, EMILY WUTHERING HEIGHTS novel DICKENS, CHARLES DOMBEY AND SON novel DICKENS, CHARLES BLEAK HOUSE novel GIBBON, EDWARD DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE history GOGOL, NIKOLAI DEAD SOULS: A NOVEL novel MELVILLE, HERMAN MOBY DICK novel MELVILLE, HERMAN BARTLEBY THE SCRIVENER short stories MELVILLE, HERMAN BENITO CERENO short stories RICHARDSON, SAMUEL PAMELA: OR VIRTUE REWARDED novel STENDHAL THE RED AND THE BLACK novel VON KLEIST, HEINRICH THE MARQUISE OF O AND OTHER STORIES short stories MID-LATE 19TH CENTURY ALCOTT, LOUISA MAY LITTLE WOMEN novel CHEKOV, ANTON TALES OF ANTON CHEKOV, VOLUMES 1-13 short stories CHEKOV, ANTON A LIFE IN LETTERS letters CRAFTS, HANNAH A BONDWOMAN’S NARRATIVE (ed. by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.) novel DOSTOYEVSKY, FYODOR CRIME AND PUNISHMENT novel ELIOT, GEORGE MIDDLEMARCH novel FLAUBERT, GUSTAVE MADAME BOVARY novel FLAUBERT, GUSTAVE A SENTIMENTAL EDUCATION novel GONCHAROV, IVAN OBLOMOV novel HAMSUN, KNUT HUNGER novel HARDY, THOMAS JUDE THE OBSCURE novel MSU MFA FICTION READING -

Books and Stories Read So Far in Books and Belief Since 1997

Books and stories read so far in Books and Belief/Faithful Readers since 1997* A Green Journey--Jon Hassler Beloved-- Toni Morrison Therapy–David Lodge Power and the Glory—Graham Greene The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe—C.S. Lewis Screwtape Letters—C.S. Lewis Sophie’s Choice—William Styron The Second Coming—Walker Percy The Plague—Albert Camus In the Beauty of the Lilies—John Updike The Sound and the Fury—William Faulkner Stones from the River—Ursula Hegi Mere Morality—Lewis Smedes Traveling Mercies—Anne Lamott The End of the Affair—Graham Greene The Sunflower—Simon Wiesenthal Things Fall Apart--Chinua Achebe Mr. Ives’ Christmas--Oscar Hijuelos A Burnt Out Case--Graham Greene Dawn--Elie Wiesel Night--Elie Wiesel The Poisonwood Bible--Barbara Kingsolver Virgin Time--Patricia Hampl Postville: Clash of Cultures--Stephen Bloom Listening for God—volumes 1, 2, 3, and 4, edited by Carlson and Hawkins A Celestial Omnibus: Short Fiction on Faith--edited by J.P. Maney and Tom Hazuka Son of Laughter by Frederick Buechner How to Be Good by Nick Hornsby The Hiding Place by Corrie Ten Boom The Fixer by Bernard Malamud Jayber Crow by Wendell Berry Gilead by Marilynne Robinson Martin Luther by Martin Marty Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton The Tempest by William Shakespeare Motherland by Fern Schumer Chapman Empire Falls by Richard Russo Life of Pi by Yann Martel The New Woman by Jon Hassler Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World by Tracy Kidder In My Hands: Memories of a Holocaust Rescuer by Irene Gut Opkyke Morte D’Urban by J.F. -

A Political Companion to Walker Percy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 7-19-2013 A Political Companion to Walker Percy Peter Augustine Lawler Berry College Brian A. Smith Montclair State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lawler, Peter Augustine and Smith, Brian A., "A Political Companion to Walker Percy" (2013). Literature in English, North America. 75. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/75 A Political Companion to Walker Percy A Political Companion to Walker Percy Edited by PETER AUGUSTINE LAWLER and BRIAN A. SMITH Copyright © 2013 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A political companion to Walker Percy / edited by Peter Augustine Lawler and Brian A.