Rabbinic Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

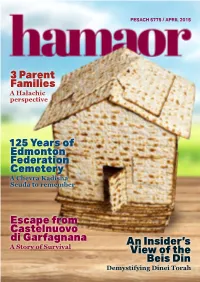

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

Understanding Mikvah

Understanding Mikvah An overview of Mikvah construction Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi S. Z. Lesches permission & comments: (514) 737-6076 4661 Van Horne, Suite 12 Montreal P.Q. H3W 1H8 Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Lesches, Schneur Zalman Understanding mikvah : an overview of mikvah construction ISBN 0-9689146-0-8 1. Mikveh--Design and construction. 2. Mikveh--History. 3. Purity, Ritual--Judaism. 4. Jewish law. I. Title. BM703.L37 2001 296.7'5 C2001-901500-3 v"c CONTENTS∗ FOREWORD .................................................................... xi Excerpts from the Rebbe’s Letters Regarding Mikvah....13 Preface...............................................................................20 The History of Mikvaos ....................................................25 A New Design.............................................................27 Importance of a Mikvah....................................................30 Building and Planning ......................................................33 Maximizing Comfort..................................................34 Eliminating Worry ......................................................35 Kosher Waters ...................................................................37 Immersing in a Spring................................................37 Oceans..........................................................................38 Rivers and Lakes .........................................................38 Swimming Pools .........................................................39 -

I. Maot Chitim II. Ta'anit Bechorim, Fast of the Firstborns III. Chametz

To The Brandeis Community, Many of us have fond memories of preparing for the holiday of Pesach (Passover), and our family's celebration of the holiday. Below is a basic outline of the major halakhic issues for Pesach this year. If anyone has questions they should be in touch with me at h[email protected]. In addition to these guidelines, a number of resources are available online from the major kashrut agencies: ● Orthodox Union: http://oukosher.org/passover/ ○ a pdf of the glossy magazine that’s been seen around campus can be found here ● Chicago Rabbinical Council: link ● Star-K: link Best wishes for a Chag Kasher ve-Sameach, Rabbi David, Ariel, Havivi, and Tiffy Pardo Please note: Since we are all spending Pesach all over the world (literally...I’m selling your chametz for you, I know) please use the internet to get appropriate halakhic times. I recommend m yzmanim.com or the really nifty sidebar on https://oukosher.org/passover/ I. Maot Chitim The Rema (Shulchan Aruch Orach Chayim 429) records the ancient custom of ma'ot chitim – providing money for poor people to buy matzah and other supplies for Pesach. A number of tzedka organizations have special Maot Chitim drives. II. Ta’anit Bechorim, Fast of the Firstborns Erev Pesach is the fast of the firstborns, to commemorate the fact that the Jewish firstborns were spared during m akat bechorot (the slaying of the firstborns). This year the fast is observed on Friday April 3 (14 Nissan) beginning at alot hashachar (i.e. -

TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning

TRANSITIONS & CELEBRATIONS: Jewish Life Cycle Guides E EW A TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning Written and compiled by Rabbi John L. Rosove Temple Israel of Hollywood INTRODUCTION The death of a loved one is so often a painful and confusing time for members of the family and dear friends. It is our hope that this “Guide” will assist you in planning the funeral as well as offer helpful information on our centuries-old Jewish burial and mourning practices. Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary (“Hillside”) has served the Southern California Jewish Community for more than seven decades and we encourage you to contact them if you need assistance at the time of need or pre-need (310.641.0707 - hillsidememorial.org). CONTENTS Pre-need preparations .................................................................................. 3 Selecting a grave, arranging for family plots ................................................. 3 Contacting clergy .......................................................................................... 3 Contacting the Mortuary and arranging for the funeral ................................. 3 Preparation of the body ................................................................................ 3 Someone to watch over the body .................................................................. 3 The timing of the funeral ............................................................................... 3 The casket and dressing the deceased for burial .......................................... -

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities by Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’S Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities By Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’s Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative A note on the content below: We acknowledge that this document invokes heavily gendered language due to the prevailing historic male voices in Jewish rabbinic and biblical perspectives, and the fact that Hebrew (the language in which these laws originated) is a gendered language. We also recognize some of these perspectives might be in contradiction with one another and with some of NCJW’s approaches to the issues of reproductive health, rights, and justice. Background Family planning has been discussed in Judaism for several thousand years. From the earliest of the ‘sages’ until today, a range of opinions has existed — opinions which can be in tension with one another and are constantly evolving. Historically these discussions have assumed that sexual intimacy happens within the framework of heterosexual marriage. A few fundamental Jewish tenets underlie any discussion of Jewish views on reproductive realities. • Protecting an existing life is paramount, even when it means a Jew must violate the most sacred laws.1 • Judaism is decidedly ‘pro-natalist,’ and strongly encourages having children. The duty of procreation is based on one of the earliest and often repeated obligations of the Torah, ‘pru u’rvu’, 2 to be ‘fruitful and multiply.’ This fundamental obligation in the Jewish tradition is technically considered only to apply to males. Of course, Jewish attitudes toward procreation have not been shaped by Jewish law alone, but have been influenced by the historic communal trauma (such as the Holocaust) and the subsequent yearning of some Jews to rebuild community through Jewish population growth. -

Bris Or Brit Milah (Ritual Circumcision) According to Jewish Law, a Healthy Baby Boy Is Circumcised on the Eighth Day After His Birth

Bris or Brit milah (ritual circumcision) According to Jewish law, a healthy baby boy is circumcised on the eighth day after his birth. The brit milah, the ritual ceremony of removing the foreskin which covers the glans of the penis, is a simple surgical procedure that can take place in the home or synagogue and marks the identification of a baby boy as a Jew. The ceremony is traditionally conducted by a mohel, a highly trained and skilled individual, although a rabbi in conjunction with a physician may perform the brit milah. The brit milah is a joyous occasion for the parents, relatives and friends who celebrate in this momentous event. At the brit milah, it is customary to appoint a kvater (a man) and a kvaterin (a woman), the equivalent of Jewish godparents, whose ritual role is to bring the child into the room for the circumcision. Another honor bestowed on a family member is the sandak, who is most often the baby’s paternal grandfather or great-grandfather. This individual traditionally holds the baby during the circumcision ceremony. The service involves a kiddush (prayer over wine), the circumcision, blessings, a dvar torah (a small teaching of the Torah) and the presentation of the Jewish name selected for the baby. During the brit milah, a chair is set aside for Elijah the prophet. Following the ceremony, a seudat mitzvah (celebratory meal) is available for the guests. Please take note: Formal invitations for a bris are not sent out. Typically, guests are notified by phone or email. The baby’s name is not given before the bris. -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

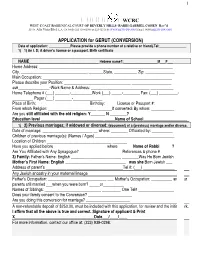

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

Britain's Orthodox Jews in Organ Donor Card Row

UK Britain's Orthodox Jews in organ donor card row By Jerome Taylor, Religious Affairs Correspondent Monday, 24 January 2011 Reuters Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has ruled that national organ donor cards are not permissable, and has advised followers not to carry them Britain’s Orthodox Jews have been plunged into the centre of an angry debate over medical ethics after the Chief Rabbi ruled that Jews should not carry organ donor cards in their current form. London’s Beth Din, which is headed by Lord Jonathan Sacks and is one of Britain’s most influential Orthodox Jewish courts, caused consternation among medical professionals earlier this month when it ruled that national organ donor cards were not permissible under halakha (Jewish law). The decision has now sparked anger from within the Orthodox Jewish community with one prominent Jewish rabbi accusing the London Beth Din of “sentencing people to death”. Judaism encourages selfless acts and almost all rabbinical authorities approve of consensual live organ donorship, such as donating a kidney. But there are disagreements among Orthodox leaders over when post- mortem donation is permissible. Liberal, Reform and many Orthodox schools of Judaism, including Israel’s chief rabbinate, allow organs to be taken from a person when they are brain dead – a condition most doctors consider to determine the point of death. But some Orthodox schools, including London’s Beth Din, have ruled that a person is only dead when their heart and lungs have stopped (cardio-respiratory failure) and forbids the taking of organs from brain dead donors. As the current donor scheme in Britain makes no allowances for such religious preferences, Rabbi Sacks and his fellow judges have advised their followers not to carry cards until changes are made. -

Report of the Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Arica

REPORT OF THE REGULATORY BOARD OF BRIT MILAH IN SOUTH AFRICA (“THE REGULATORY BOARD”) 2016 - 2018 1 Background The Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Africa was established by Chief Rabbi Dr Warren Goldstein in 2016. The Regulatory Board acts in terms of the delegated authority of the Chief Rabbi and Head of the Beth Din (Court of Jewish Law), Rabbi Moshe Kurtstag. This report covers the activities of the Regulatory Board since inception in April 2016. The number of Britot reported are for the calendar years 2016 and 2017. The Regulatory Board is responsible for: 1.1 Ensuring the very highest standards of care and safety for all infants undergoing a Brit Milah and ensuring that this sacred and holy procedure is conducted according to strict Halachic principles (Jewish law); 1.2 The development of standardised guidelines, policies and procedures to ensure that the highest standards of safety in the performance of Brit Milah are maintained in South Africa; 1.3 Ensuring the appropriate registration, training, accreditation and continuing education of practising Mohalim (plural for Mohel, a person who is trained to perform a circumcision according to Jewish law); 1.4 Maintaining all records of Brit Milahs performed in South Africa; and 1.4 Fully investigating any concerns or complaints raised regarding Brit 1 Milah with the authority to recommend and to institute the appropriate remedial action. The current members of the Regulatory Board are: Dr Richard Friedland (Chairperson). Rabbi Dr Pinhas Zekry (Expert Mohel). Rabbi Anton Klein (Beth Din Representative). Dr Reuven Jacks (Medical Officer). Dr Joseph Spitzer (Mohel and Medical Adviser). -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth