The Airline Maintenance Mechanic Educational Infrastructure: Supply, Demand, and Evolving Industry Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vendors by Managing Organization

Look up by Vendor, then look at managing dispatch. This dispatch center holds the virtual ownership of that vendor. When the vendor obtains their NAP user account, the vendor would then call this dispatch center for Web statusing permissions. You can run this list in ROSS reports: use the search function, type "vendors" or "managing" then search. Should show up. You can filter and sort as necessary. Managing Org Name Org Name Northwest Coordination Center 1-A Construction & Fire LLP Sacramento Headquarters Command Center 10 Tanker Air Carrier LLC Northwest Coordination Center 1A H&K Inc. Oregon Dept. of Forestry Coordination Center 1st Choice Contracting, Inc Missoula Interagency Dispatch Center 3 - Mor Enterprises, Inc. Southwest Area Coordination Center 310 Dust Control, LLC Oregon Dept. of Forestry Coordination Center 3b's Forestry, Incorporated State of Alaska Logistics Center 40-Mile Air, LTD Northern California Coordination Center 49 Creek Ranch LLC Northern California Coordination Center 49er Pressure Wash & Water Service, Inc. Helena Interagency Dispatch Center 4x4 Logging Teton Interagency Dispatch Center 5-D Trucking, LLC Northern California Coordination Center 6 Rivers Construction Inc Southwest Area Coordination Center 7W Enterprises LLC Northern California Coordination Center A & A Portables, Inc Northern California Coordination Center A & B Saw & Lawnmowers Shop Northern Rockies Coordination Center A & C Construction Northern California Coordination Center A & F Enterprises Eastern Idaho Interagency Fire Center A & F Excavation Southwest Area Forestry Dispatch A & G Acres Plus Northern California Coordination Center A & G Pumping, Inc. Northern California Coordination Center A & H Rents Inc Central Nevada Interagency Dispatch Center A & N Enterprises Northern California Coordination Center A & P Helicopters, Inc. -

Airliner Census Western-Built Jet and Turboprop Airliners

World airliner census Western-built jet and turboprop airliners AEROSPATIALE (NORD) 262 7 Lufthansa (600R) 2 Biman Bangladesh Airlines (300) 4 Tarom (300) 2 Africa 3 MNG Airlines (B4) 2 China Eastern Airlines (200) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (200) 1 Equatorial Int’l Airlines (A) 1 MNG Airlines (B4 Freighter) 5 Emirates (300) 1 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300) 5 Int’l Trans Air Business (A) 1 MNG Airlines (F4) 3 Emirates (300F) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300F) 1 Trans Service Airlift (B) 1 Monarch Airlines (600R) 4 Iran Air (200) 6 Uzbekistan Airways (300) 3 North/South America 4 Olympic Airlines (600R) 1 Iran Air (300) 2 White (300) 1 Aerolineas Sosa (A) 3 Onur Air (600R) 6 Iraqi Airways (300) (5) North/South America 81 RACSA (A) 1 Onur Air (B2) 1 Jordan Aviation (200) 1 Aerolineas Argentinas (300) 2 AEROSPATIALE (SUD) CARAVELLE 2 Onur Air (B4) 5 Jordan Aviation (300) 1 Air Transat (300) 11 Europe 2 Pan Air (B4 Freighter) 2 Kuwait Airways (300) 4 FedEx Express (200F) 49 WaltAir (10B) 1 Saga Airlines (B2) 1 Mahan Air (300) 2 FedEx Express (300) 7 WaltAir (11R) 1 TNT Airways (B4 Freighter) 4 Miat Mongolian Airlines (300) 1 FedEx Express (300F) 12 AIRBUS A300 408 (8) North/South America 166 (7) Pakistan Int’l Airlines (300) 12 AIRBUS A318-100 30 (48) Africa 14 Aero Union (B4 Freighter) 4 Royal Jordanian (300) 4 Europe 13 (9) Egyptair (600R) 1 American Airlines (600R) 34 Royal Jordanian (300F) 2 Air France 13 (5) Egyptair (600R Freighter) 1 ASTAR Air Cargo (B4 Freighter) 6 Yemenia (300) 4 Tarom (4) Egyptair (B4 Freighter) 2 Express.net Airlines -

Sea King Salute P16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley Looks at the Operational History of the Westland Sea King in UK Military Service

UK SEA KING SALUTE NEWS N N IO IO AT NEWS VI THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF FLIGHT Incorporating A AVIATION UK £4.50 FEBRUARY 2016 www.aviation-news.co.uk Low-cost NORWEGIAN Scandinavian Style AMBITIONS EXCLUSIVE FIREFIGHTING A-7 CORSAIR II BAe 146s & RJ85s LTV’s Bomb Truck Next-gen Airtankers SUKHOI SUPERJET Russia’s Rising Star 01_AN_FEB_16_UK.indd 1 05/01/2016 12:29 CONTENTS p20 FEATURES p11 REGULARS 20 Spain’s Multi-role Boeing 707s 04 Headlines Rodrigo Rodríguez Costa details the career of the Spanish Air Force’s Boeing 707s which have served 06 Civil News the country’s armed forces since the late 1980s. 11 Military News 26 BAe 146 & RJ85 Airtankers In North America and Australia, converted BAe 146 16 Preservation News and RJ85 airliners are being given a new lease of life working as airtankers – Frédéric Marsaly explains. 40 Flight Bag 32 Sea King Salute p16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley looks at the operational history of the Westland Sea King in UK military service. 68 Airport Movements 42 Sukhoi Superjet – Russia’s 71 Air Base Movements Rising Star Aviation News Assistant Editor James Ronayne 74 Register Review pro les the Russian regional jet with global ambitions. 48 A-7 Corsair II – LTV’s Bomb Truck p74 A veteran of both the Vietnam con ict and the rst Gulf War, the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7 Corsair II packed a punch, as Patrick Boniface describes. 58 Norwegian Ambitions Aviation News Editor Dino Carrara examines the rapid expansion of low-cost carrier Norwegian and its growing long-haul network. -

FUEL SURCHARGE EX JAPAN --- NOTE --- 1) * : All Regions Or All Regions Except Those Listed 2) the FSC of Below Carriers Is Also Applied for Minimum Charge

FUEL SURCHARGE EX JAPAN --- NOTE --- 1) * : All regions or All regions except those listed 2) The FSC of below carriers is also applied for Minimum charge. ・AF,AY,EK,KM,KL, LH,LY,MK,MU,VN: Minimum charge is 0.5kg. LH from Sep.01 ・AC,DL,ET,HY,TN,UA,WE: Minimum charge is 1kg. ・M6: Minimum FSC is \1,000.(need confirm with M6 everytimes) 3) 7L,BR,C8,CV,HX,KE,LO,MF,MU,PR,TK,YG 's effective date : date on the list + 1day (based on FLT DATE) 4) EK,TG: There are other rates for perishable cargo. 5) KE's HNL rate: only applicapable on NRT-HNL rate. Updated: Sep.01, 2021 REGION/COUNTRY/CITY EFFECTIVE DATE EXPIRE DATE RATE CODE NO AIRLINES CITY APPLIED TO REGION COUNTRY 【YYYY/MM/DD】 【YYYY/MM/DD】 (JPY/KG) CODE 3U 876 Sichuan Airlines * 20210801 99999999 55 Chargeable Weight 4B 210 AVIASTAR-TU * 20200825 99999999 0 4W 574 Allied Air * 20210701 99999999 100 Chargeable Weight 4X 805 Mercury World Cargo * 20160914 99999999 100 Chargeable Weight 5C 700 5C/C.A.L. CARGO AIRLINES * 20140815 99999999 140 Chargeable Weight 5J 203 Cebu Pacific Air * 20120418 99999999 0 5X 406 UPS Airlines * 20210801 99999999 58 Chargeable Weight 5X 406 UPS Airlines Asia 20210801 99999999 29 Chargeable Weight 5X 406 UPS Airlines Asia China 20210801 99999999 20 Chargeable Weight 5X 406 UPS Airlines Asia Hong Kong 20210801 99999999 20 Chargeable Weight 5X 406 UPS Airlines Asia Philippines 20210801 99999999 20 Chargeable Weight 5X 406 UPS Airlines Asia South Korea 20210801 99999999 20 Chargeable Weight 5X 406 UPS Airlines Asia Taiwan 20210801 99999999 20 Chargeable Weight 5X 406 -

Lockheed P-38 Lightning

Last updated 1 July 2021 |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| LOCKHEED P-38 LIGHTNING |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| Considerable confusion exists over civilian P-38 identities. When purchased from military disposals immediately after WWII, the USAAF serial number and Lockheed c/n were quoted on the Bill of Sale. Subsequent research reveals that those sold from Kingman AZ often quoted a mis-matched c/n, probably based a listing that differs from the official company Lockheed number/USAAF serial tie-ups. This dubious c/n was then given to CAA as part of the registration paperwork, and accompanied the aircraft for its civil life. Because P-38s were delivered without a Lockheed manufacturers plate, it can not be easily clarified. 5266 P-38E 41-2048 Lockheed Aircraft Co, Burbank CA 43/46 RP-38E (test aircraft, modified cockpit area) NX91300 Lockheed Aircraft Co, Burbank CA 3.46/54 (test aircraft for Lockheed XF-90 program) N91300 Hycon Aerial Surveys, Ontario CA 8.54/62 (survey conv. at Ontario CA .54: P-38L engines and components, extended survey nose; magnetometer survey ops. in South America) (last FAA inspection 11.57, wfu, open storage Las Vegas NV 59/62) Don M. May, Phoenix AZ 25.6.62 Kucera & Associates, Cleveland OH: not del. 10.62 crashed on takeoff, Phoenix AZ (May k) 24.10.62 ________________________________________________________________________________________ 5757 • P-38F 41-7630 forced landing Greenland, on del. to England 15.7.42 (with 5 other P-38s & B-17: all buried by snow) Pat Epps/ Greenland Expedition Society .81/94 (recov. from under 260 feet of ice .90/92) N5757 Roy Shoffner/ Greenland Expedition Society, Atlanta GA 12.1.94/02 (recov. -

Section 9 MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT 9.0

Section 9 MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT 9.0 Introduction The long-range plan includes both long-range and short-range strategies/actions that lead to the development of an integrated intermodal transportation system that facilitates the efficient movement of people and goods. Intermodalism attempts to help all modes work better by providing cross-modal connections to the transportation system. Currently, the urban area has excellent linkage between the Huntsville International Airport and the highway system via I-565. The International Intermodal Center (IIC) is located at the airport and is connected by spur to a main line of the Norfolk Southern Railroad. There is currently no direct connection to the Tennessee/Tombigbee Waterway approximately 5.5 miles south of the airport at the Tennessee River. A River Port Development Study was conducted during 2000 identifying potential locations for river terminal sites in Huntsville, important to capture additional economic markets. As a result of this study, property was acquired for future port development. Cargo waterway service is available in nearby Decatur offering barge service for bulk commodities and general cargo providing access for customers to the IIC and I-565. A major concern in the Tennessee Valley has been the lack of limited access interstate highway facilities connecting the Huntsville urban area with major cities to the east and west, Memphis, Atlanta and Chattanooga. The area has been essentially left out of the interstate system since the system was designed before Huntsville grew to become a major urban area. Studies have been conducted to determine the best feasible route to connect the Huntsville urban area with Memphis, Atlanta and Chattanooga. -

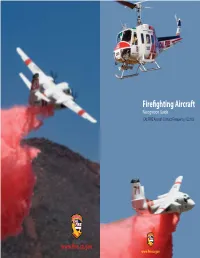

Firefighting Aircraft

Firefi ghting Aircraft Recognition Guide CAL FIRE Aircraft Contact Frequency 122.925 www.fi re.ca.gov Glossary Firefi ghting Aircraft means support of the fi refi ghters on the ground from aircraft in the air. Aircraft can access steep, rocky or unsafe areas before ground forces are able to gain entry. CAL FIRE has the largest state owned fi refi ghting air fl eet including 23 airtankers, 11 helicopters and 14 air attack aircraft. Air Attack or Air Tactical Aircraft is an airplane that fl ies over an incident, providing tactical coordination with the incident commander on the ground, History and directing airtankers and helicopters to critical areas of a fi re for retardant and water drops. CAL FIRE uses OV-10As for its air attack missions. The CAL FIRE Air Program has long been the premier fi refi ghting aviation program in the world. CAL FIRE’s fl eet of over 50 fi xed wing and rotary wing, Airtanker is a fi xed-wing aircraft that can carry fi re retardant or water and make it the largest department owned fl eet of aerial fi refi ghting equipment in drop it on or in front of a fi re to help slow the fi re down. CAL FIRE uses Grum- the world. CAL FIRE’s aircraft are strategically located throughout the state at man S-2T airtankers for fast initial attack delivery of fi re retardant on wildland CAL FIRE ‘s 13 airbases and nine helicopter bases. fi res. The S-2T carries 1,200 gallons of retardant and has a crew of one – the pilot. -

Recent Developments in Aviation Law Donald R

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 78 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 Recent Developments in Aviation Law Donald R. Andersen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Donald R. Andersen, Recent Developments in Aviation Law, 78 J. Air L. & Com. 219 (2013) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol78/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN AVIATION LAW DONALD R. ANDERSEN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. MONTREAL CONVENTION .................. 220 II. FOREIGN SOVEREIGN IMMUNITIES ACT ....... 224 III. FEDERAL AVIATION ACT OF 1958............... 227 IV. AIRLINE DEREGULATION ACT-FEDERAL PREEMPTION .............................. 232 V. FEDERAL PREEMPTION-OTHER FEDERAL STATUTES ................................ 239 A. AIR CARRIER ACCESs ACT OF 1986- DISCRIMINATION IN BOARDING .................. 239 B. FAA AUTHORIZATION ACT OF 1994 ........... 243 C. 49 U.S.C. §44112 ........................ 244 VI. FEDERAL TORT CLAIMS ACT................ 246 VII. PRODUCTS LIABILITY....................... 251 A. FLIGHT TRAINING ............................... 251 B. GENERAL AVIATION REVITALIZATION ACT ........ 255 VIII. JURISDICTION AND PROCEDURE ............. 263 A. PERSONAL JURISDICTION......................... 263 1. Jurisdiction over Non-U.S. Manufacturersfor Accidents in the -

DRAW Decal Pricelist Price List, Effective 03-05-16 2016 Releases

DRAW Decal Pricelist Price List, effective 03-05-16 2016 Releases Scale Set Description 24 24-P51-4 Bob Hoover "Rockwell" P-51D ¥5,000 24 24-P51-5 "Miracle Maker" P-51D ¥4,000 24 24-P51-9 "Bardahl Special" P-51D 1964 version ¥3,000 24 24-P51-10 "Geraldine" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends ¥4,000 24 24-P51-11 "Glamorous Gal" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends ¥4,000 24 24-P51-12 "Cloud Dancer" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends ¥6,000 24 24-P51-13 "Dakota Kid II" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends ¥4,000 24 24-P51-14 "American Beauty" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends ¥8,000 24 24-P51-15 "Slender, Tender and Tall" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends¥4,000 24 24-P51-16 "Quick Silver" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends ¥3,000 24 24-P51-17 "Sparky" P-51D Gathering of Mustangs and Legends ¥7,000 32 32-Cobra-1 USFS Firewatch Cobras ¥3,000 32 32-Corsair-1 "Lancer Two" F4U-4 Corsair Reno 1968-69 ¥3,000 32 32-Corsair-2 "Korean War Hero" Tobul F4U-4 Corsair ¥3,000 32 32-F6F-1 "Little Nugget" Hellcat Racer, Alaska Golden Nugget Scheme ¥3,000 32 32-F6F-2 Blue Angels Hellcat ¥2,400 32 32-F8F-1 Blue Angels Bearcats ¥2,400 32 32-F8F-2 Blue Angels "Beetle Bomb" Bearcat ¥2,000 32 32-F8F-3 "Smirnoff" F8F-2 Bearcat, Mira Slovak 1964-1965 Reno ¥2,400 32 32-Huey-1 NASA UH-1D Huey's ¥2,400 32 32-Huey-2 HELiPRO New Zealand Huey ¥2,000 32 32-Huey-3 National Science Foundation Hueys ¥2,400 32 32-Huey-4 North Carolina Forestry Service UH-1H Huey ¥2,000 32 32-Huey-6 Multinational Force & Observers UH-1V Hueys ¥2,000 32 32-OV10-1 -

AIA CONFERENCE May 2014

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN AVIATION LAW AIA CONFERENCE May 2014 Donald R. Andersen Taylor English Duma LLP Atlanta, Georgia 404.291.3429 [email protected] . 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. MONTREAL CONVENTION .............................................................................. 1 B. FOREIGN SOVEREIGN IMMUNITIES ACT..................................................... 5 C. FEDERAL AVIATION ACT OF 1958 ................................................................. 9 D. AIRLINE DEREGULATION ACT (“ADA”) – FEDERAL PREEMPTION .................................................................................................... 15 E. FEDERAL PREEMPTION – OTHER FEDERAL STATUTES ........................ 24 1. Air Carrier Access Act of 1986 – Discrimination in Boarding ............... 24 2. FAA Authorization Act of 1994 .............................................................. 28 3. 49 U.S.C. § 44112 .................................................................................... 30 F. FEDERAL TORT CLAIMS ACT ....................................................................... 31 G. PRODUCT LIABILITY ...................................................................................... 38 1. Flight Training ......................................................................................... 38 2. General Aviation Revitalization Act ........................................................ 43 H. JURISDICTION AND PROCEDURE ................................................................ 52 1. Personal Jurisdiction ............................................................................... -

Japan Export Air Freight Security Surcharge

Updated September 16, 2021 Effective Carrier Destination Security Surcharge JPY Date 5C C.A.L. Cargo All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 18/kg 21-Apr-09 5J Cebu Pacific Air All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 5X UPS All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 15/kg 1-Mar-20 6R Aero Union All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 7C Jeju Air All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Aug-18 7L Silk Way West Airlines LLC All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Jun-19 AA American Airlines All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 15/kg 1-Mar-20 AC Air Canada All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 AI Air India All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 AM Aeromexico All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 AF Air France All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 6/kg 1-Feb-20 AY Finnair All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 AZ Alitalia All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 1/kg 01-Apr-18 BA British Airways All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 15/kg 1-Mar-20 BR EVA AIR All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 CA Air China International All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 CF China Air Cargo All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 CI China Airlines All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 15/kg 1-Mar-20 CK China Cargo Airlines All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 CV Cargolux Airlines International All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 CX Cathay Pacific Airways All Destinations Min. JPY260 or 15/kg 1-Mar-20 CZ China Southern Airlines All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 EK Emirates Airlines All Destinations JPY260/HAWB 01-Nov-16 ET Ethiopian Airline All Destinations Min. -

Fairchild At-21 Gunner

Last updated 3 November 2019 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| FAIRCHILD AT-21 GUNNER ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 2 AT-21 - NX63432 C. G. Reavis, Downey CA 7.2.47/55 (photo painted in civilian scheme) struck-off USCR 14.11.55 ________________________________________________________________________________________ - AT-21 42-48071 N53540 reg. CC-LNG reg. ________________________________________________________________________________________ - AT-21 42-48075 NX33690 Donald A. Hackett, CA .46 ________________________________________________________________________________________ - AT-21 42-48081 N53541 reg. CC-CEB reg. LV-RZD reg. 13.7.49 ________________________________________________________________________________________ - AT-21 42-48084 CC-PLAS (1 reg. ________________________________________________________________________________________ - AT-21 42-48440 N64468 Clyde Sturgell, Tuscola IL 64 ________________________________________________________________________________________ - AT-21 42-76641 CC-PLAS (2 reg. ________________________________________________________________________________________ 19 AT-21 N64469 Clyde Sturgell, Tuscola IL 64 ________________________________________________________________________________________