Indian-Occupied Kashmir? Written by Sahil Mathur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Film and Photography Industries

Join us for a fascinating panel discussion that traces the trajectory and evolution of the Film and Photography Industries For Immediate Release Avid Learning presents The Changing Face of the Image: The Evolution of the Film and Photography Industries – a live session on how the image making industries of film and photography have changed and evolved – over the years – with the advent of newer technologies and the emergence of fresh artistic perspectives, philosophies and concepts. Award-winning Photographer and Installation Artist Samar Singh Jodha, Award-winning Filmmaker and Photographer Sooni Taraporevala and Oscar-nominated and Two-time National Award-winning Filmmaker Ashvin Kumar will be in conversation with Media Expert and ex-head of the SCM (Social Communications Media) Post-Graduate Course at Sophia Polytechnic Jeroo Mulla. Please read on for more details: Photography and film are two genres that share many synergies and which have both had an interesting history, first being connected to science and the various iterations and adaptations of light, then struggling to be recognized as fine art, and now, with the digital age, the concept of what these two fields entail is constantly changing as are the practitioners themselves. Our cell phones are now packing image making tools that surpass the technology of most digital cameras from fifteen years ago. The shift from analogue to digital photography has elicited diverse reactions from media scholars. While some have written the obituary of photography as the dominant visual medium of the modern world, other scholars see digitisation as merely a means for the continuation or enhancement of this dominant medium. -

Top 200+ Current Affairs Monthly MCQ's September

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 1 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q1.India's first-ever sky cycling park to be opened in which city? (a) Manali (b) Mussoorie (c) Nainital (d) Shimla (e) None of these Ans.1.(a) Exp.To boost tourism and give and an all new experience to visitors, India's first-ever sky cycling park will soon open at Gulaba area near Manali in Himachal Pradesh. It is 350m long & is located at a height of 9000 Feet above sea level. Forest Department and Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Mountaineering and Allied Sports have jointly developed an eco-friendly park. AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 2 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q2.Which sportsperson has won the 2019 Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar? (a) Abhinav Bindra (b) Jeev Milkha Singh (c) Mary Kom (d) Gagan Narang (e) None of these Ans.2.(d) Exp.On 2019 National Sports Day (NSD), Gagan Narang and Pawan Singh have been honoured with the Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar for their Gagan Narang Sports Promotion Foundation (GNSPF) at the Arjuna Awards ceremony in Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi. The award recognizes their contribution in the growth of their favourite sport and a reward for sacrifices they have made to realize their dream. In 2011, Narang and co-founder Pawan Singh founded GNSPF to nurture budding talent -

WEEKLY Saturday, August 7 ! 2010 ! Issue No

Established in 1936 The Doon School WEEKLY Saturday, August 7 ! 2010 ! Issue No. 2253 FLOUNDER’S REGULARS COMMONWEALTH ART INTERVIEW 2 3 3 DAY 4 Editorial And The Leaves That Are Green Eighteen Holes We returned to a variety of brilliant shades of green, which and Counting... reflected the brightness on our many faces. The grass on the Main Shashvat Dhandhania reflects on the School’s perfor- Field and Skinner’s was dense and even. Trampled tracks and mance in The Doon School Golf Trophy, 2010, held in patches had grown back considerably. The whitewashing was Kathmandu, Nepal, on June 19 and 20. Since boys started playing golf in School quite re- washed away, here and there. Buildings were damp. Moss discoloured cently, we have not been playing regular fixtures! How- the bricks and concrete . The plants and trees, much like our hair, ever. after making a good start in Chandigarh last year, were not disciplined in their growth and grooming. These pristine made our hopes go up as we travelled with SJB to Nepal, fields of grass, sparkling smiles and audacious growth are nothing to play golf with the British School, Kathmandu. This a few days of term would not fix: a few days of football, classes, time the younger players in School were given a chance. PT and the rest of the routine. This was – at least in my eyes – a way to make new We found a few cosmetic changes around the campus. The acquaintances and expand our golfing circuit. HM’s office, for one. Not too many construction barricades re- The tournament was held between June 19 and 20. -

Ladakh Studies 25

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES NR. 25 February 2010 Contents LETTER FROM THE EDITOR. Kim Gutschow. 2 ESSAYS: Climate Change in Ladakh. Sunder Paul 3 Conservation and livelihoods through Himalayan Homestays. Rinchen Wangchuk. x BOOK REVIEWS: Dieter Schuh. 2008. Herrscherurkunden und Privaturkunden aus Westtibet (Ladakh). Reviewed by John Bray x L. Berzenczey. 2007. Adventures in Central Asia. A Hungarian in the Great Game. Edited by Peter Marczell. Reviewed by John Bray x IALS NEWS & NOTES Conference Report, Monisha Ahmed and John Bray x Conference Program of the 14th IALS Colloquium x Publication Announcement, John Bray NEWS FROM LADAKH. Abdul Nasir Khan x LADAKH BIBLIOGRAPHY SUPPLEMENT No 20. John Bray x Letter from the Editor In July of 2009, the IALS held what appears to have been one of the largest conferences the organization has ever held, judging by number of papers and participants. I refer readers to the full conference report by Monisha Ahmed and John Bray, but wish to congratulate all in the IALS and on the ground in Ladakh as well as Jammu & Kashmir who helped make the conference such a success. The conference sparked lively debate in the IALS about topics including but not limited to the constitution, conference venues, future IALS commitments, and publications. As editor of Ladakh Studies and keenly interested in the future of IALS publications, I will mention some key concerns that arose during the conference and that will no doubt be subject of discussion at Aberdeen. The IALS Executive and Advisory Committee held a meeting before the conference began to discuss among other issues, sales of current IALS publications and Ladakh Studies in Ladakh, India, and the wider world. -

Transfer of Equity Shares to IE

UPL Limited Statement of Unclaimed dividend amount consecutively for 7 years, whose shares are to be transferred to IEPF Suspense Account Sr No FolioNo name Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Pincode IEPFHolding 1 0000280 ABHAYA KUMAR GUPTA J-7 HARIDWAR EVERSHINE NAGAR MALAD WEST BOMBAY 0 0 160 2 0000420 NEEMA BHUPENDRA PURI SHEETAL KUNJ CO OP HSG SOC PLOT NO 408 4 GIDC VAPI BULSAR 0 0 80 3 0000427 MAHESH K A PATHANIA MAHESH K A PATHANIA 117 UPL NO 1 GIDC ANKLESHWAR 0 0 80 4 0000428 MAHESH KUMAR A PATHANIA MAHESH KUMAR A PATHANIA 117 UPL NO 1 GIDC ANKLESHWAR 0 0 80 5 0000429 P N PARAMESWARAN MOOTHATHU 0 0 80 6 0000430 P N PARAMESWARAN MOOTHATHU 0 0 80 7 0000431 P N PARAMESWARAN MOOTHATHU 0 0 80 8 0000435 VIVEK VIJAY BHIDE VIVEK VIJAY BHIDE POST BOX NO 9 750 GIDC JHAGADIA DUSTT BHARUCH 0 0 80 9 0000667 JASVANTSINH S RANA 1761 A PANCHSHIL SOC SARDARNAGAR BHAVNAGAR 0 0 80 10 0000846 MARIA R DSILVA UNITED PHOSPHORUS LTD 9 CROFTS AVENUE HURSTVILLE (SYDENY) NSW 2220 0 0 80 11 0001150 ARIF KAYDAWALA P O BOX NO 22741 SAFAT 13088 KUWAIT 0 0 160 12 0001167 DINESH KURJI VITHLANI 138 POWYS LANE PALMERS GREEN LONDON N 13 UHN UK 0 0 410 13 0001253 SUNIL MALHOTRA P O BOX 51511 DUBAI UAE 0 0 4160 14 0001267 SUDESH SHARMA C/O ADCO ENGG & MAJOR PROJECTS O O BOX 270 ABU DHABI UAE 0 0 830 15 0001319 MARCIANO FRANCISCO RODRIGUES P O BOX 46111 ABU DHABI UAE 0 0 830 16 0001376 SANJAY MEHTA C/O AWLAD NASER CORP P O BOX 46611 ABU DHABI U A E 0 0 830 17 0001382 PUTHUSSERY DEVASSY JOSE FBI P B NO 812 DUBAI UAE 0 0 205 18 0001506 BHUPINDER NATH MALHOTRA P O BOX -

Media in India &Censorship in India. Media in India

Media in India &Censorship in India. Media in India Media has played a significant role in establishing democracy throughout the world. Since the 18th century, the media has been instrumental in reaching the masses and equipping them with knowledge, especially during the American Independence movement and French Revolution. Media is considered as “Fourth Pillar” in democratic countries along with Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary, as without a free media democratic system cannot cease to exist. Media became a source of information for the citizens of colonial India, as they became aware of the arbitrariness of the British colonial rule. Thus, gave a newfound force to India’s Independence movement, as millions of Indians joined the leaders in their fight against the British imperialism. The role of media in Indian democracy has undergone massive changes, from the days of press censorship during Emergency in 1975 to being influential in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. Transition from print to electronic Indian media has traveled a long way, from the days of newspaper and radio to present-day age of Television and Social Media. The liberalisation of Indian economy in the 1990s saw an influx of investment in the media houses, as large corporate houses, business tycoons, political elites, and industrialists saw this as an opportunity to improve their brand image. The news channels were now involved in the showbiz industry, as TRPs became a cause of rivalry amongst news houses. News that was seen as medium to educate the people on issues that were of utmost important for the society, became a source of biased viewpoints. -

BJP, Cong Spar Over Family in Chargesheet Says Won’T Fight

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 WORLD 11 SPORT 16 Published From GET REAL ABOUT US, CHINA CLOSE TO KINGS XI FACE CHENNAI DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL BHUBANESWAR STRIKING A DEAL: TRUMP RANCHI RAIPUR CHANDIGARH REAL ESTATE SUPER KINGS IN IPL DEHRADUN HYDERABAD VIJAYWADA Late City Vol. 155 Issue 92 LUCKNOW, SATURDAY APRIL 6, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable ANUPAM KHER LAUDS RANBIR KAPOOR} } 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com Sumitra makes BJP ‘worry-free’, BJP, Cong spar over Family in chargesheet says won’t fight ED Agusta charges raise political storm: Modi slams * The Congress called the ED LS poll this time chargesheet as “cheap political stunt” to divert people’s attention from the Family; Cong calls agency move cheap political stunt ‘imminent defeat’ of the BJP in polls PNS n NEW DELHI/DEHRADUN “panic-stricken” Modi and fair trial rights override * Arun Jaitley insisted that the Government is using “rehashed media rights and the court can Opposition party must answer as to he ED’s supplementary insinuations” through its “pup- temporarily curtail the freedom who are ‘RG’, ‘AP’ and ‘FAM’ in the Tchargesheet in the pet” ED, which it dubbed as of the media to ensure that. documents cited by the probe agency AgustaWestland chopper scam “Election Dhakosla” (sham) * Modi claimed that Michel whom his case raised the political tem- for “manufacturing lies”. Government had brought from Dubai perature ahead of the Lok “A single uncertified had disclosed two Sabha polls with Prime page leaked by ED of a names to his Minister Narendra Modi on purported chargesheet is a interrogators DEEPAK K UPRETI n NEW DELHI Arun Jaitley addresses the media in New Delhi on Friday PTI Friday bringing it up to attack cheap election stunt to divert * One was ‘AP’ the Congress even as alleged attention from imminent and the other mid speculation about her middleman Christian Michel defeat of the Modi was ‘FAM’. -

Final 40 Page Jan 2012.Qxd

VOL. 9 NO. 7 MAY 2012 www.civilsocietyonline.com `50 CIVIC ACTIVISM AND OUR CITIES WWWhhhEEERRREEE IIISSS TTThhhEEE RRRIIISSSIIINNNggg MMMIIIDDDDDDlllEEE CCClllAAASSSSSS??? ITI s GET A BAlA In GAME cHAnGERs REBEl fIlM GAIns GROund MAKEOVER As Pages 6-7 Pages 31-32 RAdIcAl nREGA unIOn BOAT RIdE TO sEE sRInAGAR cOMpAnIEs Pages 8-9 Pages 32-33 sEEK sKIlls sTORM In JARAwA BuffER ‘THE sHORT sTORy lIBERATEs’ Pages 27-28 Page 12 Pages 34-35 CONTENTs READ U S. WE READ YO U. Cities and citizens his magazine’s coverage of both the middle class and our cities goes back many years now. Our second cover story in 2003 was on tBhagidari and sheila Dikshit and from then on we have closely tracked Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) and other such formations in urban environments across the country. it has always been obvious to us that india’s future is closely tied to how well it manages its cities. Unfortunately the decay we are witness - COVER STORY ing is unnerving. Clearly new values and ideas are needed and as has happened elsewhere in the world they will come from a rising middle class. where is the rising middle class? it is important to go in search of best practices and see how solutions People from the middle class come out from time to time to are being found as the rest of the world also grapples with urban chal - protest bad roads, crime and corruption. They have also learnt lenges. This is as necessary with regard to green technologies as with sys - to demand better civic services. -

WEEKLY Saturday, October 30 ! 2010 ! Issue No

Established in 1936 The Doon School WEEKLY Saturday, October 30 ! 2010 ! Issue No. 2265 OLYMPIAN FOUNDER’S REGULARS BASKI REPORT 2 3 PROSPECTS 5 SPEECH- I 6 DS-75 ROUND-UP Editorial Shatam Ray reports on the celebrations of the DS-75 Founder’ s At the end of a much celebrated Platinum Jubi- Day lee, the Publication Room bore a desolate air: until Sir, your identity card please. Thursday evening! While all publications have done Huh? What identity? their bit for the term, the Weekly is going to start The identity card School must have issued to you? afresh with a new Board and a change in editorial Oh right. I forgot. policy. And Founder’s had begun. Almost overnight the campus was In my article titled ‘Beyond Boundaries’ in the transformed. The raw woodwork was made into an impos- Founder’s Day Special Edition, I pointed out that ing stage. The naked bamboo poles were transformed into the Weekly needed to address comtemporary issues to elegant shamianas. Even the bajri felt a little softer, or maybe a greater extent. I also elaborated on our plan to do not. DS75 celebrations were the most anticipated event since so in the future. Every week we will have a section the beginning of the term and personally, since this was my that will be addressing some topical issue. For in- first Founder’s, I was looking forward to the event with ex- stance, this week we have featured a debate about citement. To write a review for the four days that were to whether India should host the Olympics or not. -

WEEKLY Saturday, November 25, 2006 ! Issue No

Established in 1936 The Doon School WEEKLY Saturday, November 25, 2006 ! Issue No. 2137 ’S C FOUNDER FILM ROSSWORD REGULARS2 22 5 4 SPEECH3 FOCUS 6 Live from the Battlefield Shikhar Singh and Ashish Mitter interviewed the eminent journalist Ajai Shukla on his recent visit The Doon School Weekly (DSW): Just how independent is the In- dian media? Ajai Shukla (AJS): I would say that it is fairly independent: at least far more so than it has been before. In fact, while the government might be able to influence the print media, it has limited control over the electronic media. Television channels, for example, earn most of their revenue from private advertising. There are really very few government advertisements on TV. In India today, editorial pressures are from within. The government really has very little say. DSW: You had mentioned briefly in your talk that the way the Indian media had covered the Kargil conflict was far from satisfactory. But is it really possible to remain unbiased at such a time? AJS: It is really difficult to divorce yourself from a bias while reporting. But a personal bias is no excuse for not reporting real, hard facts. Let me give you an example. In conflict areas such as Jammu & Kashmir or Nagaland, the army tries to make the entire country believe that we are in a perpetual state of war. But often we are not. In J&K in particular, the army is almost completely engaged in operations against local Kashmiris, who are, at the end of day, Indian citizens. -

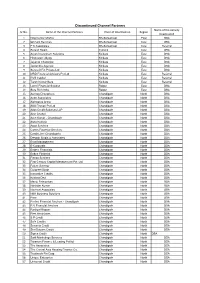

List of Discontinued Channel Partners As on June 30, 2018 Sr.No

List of Discontinued Channel Partners As On June 30, 2018 Sr.No. Name of the Channel Partners Place of Deactivation Region Name of the Activity Deactivated 1 Susheel T Dubey Mumbai West DSA 2 Dyana Grover Noida North DSA 3 Satish Amale Mumbai West Referral 4 New Heights Financial Planners Pvt. Ltd. Delhi North DSA 5 Deepak Kumar Ghaziabad North Referral 6 V P Associates Jaipur North DSA 7 Satish Amale Mumbai West Referral 8 Neeraj Sharma Delhi North Referral 9 Abhishek Pradhan Noida North DSA 10 Destimoney Financial Services Pvt. Ltd Mumbai Pan India DSA 11 Trust One Capital Partners Pvt. Ltd. Delhi North DSA 12 Dynamic Solutions Delhi North DSA 13 Orimark Services Bhubaneshwar East DSA 14 Jayanta Chatterjee Kolkata East DSA 15 Safe Credits Chandigarh North DSA 16 Raba Fincorp Chennai South DSA 17 Cortes Financial Services Chandigarh North DSA 18 Lalit Sharma Mumbai West DSA 19 Arya Finance Mumbai West DSA 20 Arya Associate Mumbai West DSA 21 Kutub S Rassiwala Mumbai West DSA 22 Prime Capital Solutions Mumbai West DSA 23 Ripa Kakkad Mumbai West DSA 24 Step Up Business Services P Ltd Mumbai West DSA 25 AMS Financial and Realtors Mumbai West DSA 26 Shankar Rajapkar Financial Advisory Mumbai West DSA 27 Varsha Ashvin Kumar Sheth Mumbai West DSA 28 Green Channel Financial Consultancy Services Ltd Mumbai West DSA 29 Anita D Mejari Mumbai West DSA 30 Vindhya Sankpal Mumbai West DSA 31 Palache Capital Mumbai West DSA 32 Global Solutions Ahmedabad West DSA 33 Sunrise Fincorp Bangalore South DSA 34 Eclat Management Chandigarh North DSA 35 NBK -

Discontinued Channel Partners Name of the Activity Sr.No

Discontinued Channel Partners Name of the Activity Sr.No. Name of the Channel Partners Place of Deactivation Region Deactivated 1 Dilip Kumar Mishra Bhubaneshwar East DSA 2 Orimark Services Bhubaneshwar East DSA 3 P K Associates Bhubaneshwar East Referral 4 Suresh Swain Cuttack East DSA 5 Aryan Investment Solutions Kolkata East DSA 6 Hindustan Udyog Kolkata East DSA 7 Jayanta Chatterjee Kolkata East DSA 8 Jeetendra Agarwal Kolkata East DSA 9 Servo-O Fin Private Ltd Kolkata East DSA 10 MRD Financial Advisory Pvt Ltd Kolkata East Referral 11 RVS Capital Kolkata East Referral 12 Tarun Kumar Bera Kolkata East Referral 13 Laxmi Financial Solution Raipur East DSA 14 Sure Rich Infra Raipur East DSA 15 Aar kay Enterprises Chandigarh North DSA 16 Aeon Associates Chandigarh North DSA 17 Aishwarya Arora Chandigarh North DSA 18 AKS Finman Pvt Ltd Chandigarh North DSA 19 Align Credit Solutions LLP Chandigarh North DSA 20 Amit Chahal Chandigarh North DSA 21 Arun Kumar - Chandigarh Chandigarh North DSA 22 Asha Kukreja Chandigarh North DSA 23 Astar Services Chandigarh North DSA 24 Cortes Financial Services Chandigarh North DSA 25 Credit Line (Chandigarh) Chandigarh North DSA 26 Deepak Singla & Associates Chandigarh North DSA 27 Eclat Management Chandigarh North DSA 28 E-Corporate Chandigarh North DSA 29 Embee Financials Chandigarh North DSA 30 Enbee Financial Chandigarh North DSA 31 Finnox Services Chandigarh North DSA 32 First Century Capital Management Pvt. Ltd. Chandigarh North DSA 33 Future Synergy Chandigarh North DSA 34 Gurpreet Singh Chandigarh