Internal Diseases Propedeutics (Part I). Diagnostics of Pulmonary Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap in Head and Neck Reconstruction

European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck diseases 132 (2015) 291–294 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com Technical note Supraclavicular artery island flap in head and neck reconstruction a b a,c a,∗,c S. Atallah , A. Guth , F. Chabolle , C.-A. Bach a Service de chirurgie ORL et cervico-faciale, hôpital Foch, 40 rue Worth, 92150 Suresnes, France b Service de radiologie, hôpital Foch, 40, rue Worth, 92150 Suresnes, France c Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, UFR de médecine Paris Ouest Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, 78280 Guyancourt, France a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Keywords: Due to the complex anatomy of the head and neck, a wide range of pedicled or free flaps must be available Supraclavicular artery island flap to ensure optimal reconstruction of the various defects resulting from cancer surgery. The supraclavi- Fasciocutaneous flap cular artery island flap is a fasciocutaneous flap harvested from the supraclavicular and deltoid regions. Head and neck cancer The blood supply of this flap is derived from the supraclavicular artery, a direct cutaneous branch of the Reconstructive surgery transverse cervical artery in 93% of cases or the supraclavicular artery in 7% of cases. The supraclavicular artery is located in a triangle delineated by the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle medi- ally, the external jugular vein posteriorly, and the median portion of the clavicle anteriorly. -

The Stethoscope: Some Preliminary Investigations

695 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The stethoscope: some preliminary investigations P D Welsby, G Parry, D Smith Postgrad Med J: first published as on 5 January 2004. Downloaded from ............................................................................................................................... See end of article for Postgrad Med J 2003;79:695–698 authors’ affiliations ....................... Correspondence to: Dr Philip D Welsby, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK; [email protected] Submitted 21 April 2003 Textbooks, clinicians, and medical teachers differ as to whether the stethoscope bell or diaphragm should Accepted 30 June 2003 be used for auscultating respiratory sounds at the chest wall. Logic and our results suggest that stethoscope ....................... diaphragms are more appropriate. HISTORICAL ASPECTS note is increased as the amplitude of the sound rises, Hippocrates advised ‘‘immediate auscultation’’ (the applica- resulting in masking of higher frequency components by tion of the ear to the patient’s chest) to hear ‘‘transmitted lower frequencies—‘‘turning up the volume accentuates the sounds from within’’. However, in 1816 a French doctor, base’’ as anyone with teenage children will have noted. Rene´The´ophile Hyacinth Laennec invented the stethoscope,1 Breath sounds are generated by turbulent air flow in the which thereafter became the identity symbol of the physician. trachea and proximal bronchi. Airflow in the small airways Laennec apparently had observed two children sending and alveoli is of lower velocity and laminar in type and is 6 signals to each other by scraping one end of a long piece of therefore silent. What is heard at the chest wall depends on solid wood with a pin, and listening with an ear pressed to the conductive and filtering effect of lung tissue and the the other end.2 Later, in 1816, Laennec was called to a young characteristics of the chest wall. -

Myocardial Hamartoma As a Cause of VF Cardiac Arrest in an Infant a Frampton, L Gray, S Bell

590 CASE REPORTS Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.2003.009951 on 26 July 2005. Downloaded from Myocardial hamartoma as a cause of VF cardiac arrest in an infant A Frampton, L Gray, S Bell ............................................................................................................................... Emerg Med J 2005;22:590–591. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.009951 ardiac arrests in children are fortunately rare and the patients. However a review by Young et al2 found that the presenting cardiac rhythm is often asystole. However, survival to hospital discharge in infants and children Cventricular fibrillation (VF) can occur and may respond presenting with VF/VT was of the order of 30%, compared favourably to defibrillation. with only 5% of patients whose initial presenting rhythm was asystole. VF has also been demonstrated to be relatively more CASE REPORT common in infants than any other paediatric age group A 7 month old girl was sitting in her high chair when she was (p,0.006).1 One study of over 500 000 children presenting to witnessed by her parents to collapse suddenly at 1707 hours. an ED over a period of 5 years found VF to be the third most They attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and the common presenting cardiac arrhythmia of any origin in ambulance crew arrived 7 minutes later, the cardiac monitor infants below the age of 1 year.1 It has been suggested that a displaying VF. No defibrillation or medications were admi- subgroup of patients (those ,1 year old) that would benefit nistered and she was rapidly transferred to her nearest from early defibrillation can be identified.2 emergency department (ED), arriving at 1723. -

Respiratory Examination Cardiac Examination Is an Essential Part of the Respiratory Assessment and Vice Versa

Respiratory examination Cardiac examination is an essential part of the respiratory assessment and vice versa. # Subject steps Pictures Notes Preparation: Pre-exam Checklist: A Very important. WIPE Be the one. 1 Wash your hands. Wash your hands in Introduce yourself to the patient, confirm front of the examiner or bring a sanitizer with 2 patient’s ID, explain the examination & you. take consent. Positioning of the patient and his/her (Position the patient in a 3 1 2 Privacy. 90 degree sitting position) and uncover Exposure. full exposure of the trunk. his/her upper body. 4 (if you could not, tell the examiner from the beginning). 3 4 Examination: General appearance: B (ABC2DEVs) Appearance: young, middle aged, or old, Begin by observing the and looks generally ill or well. patient's general health from the end of the bed. Observe the patient's general appearance (age, Around the bed I can't state of health, nutritional status and any other see any medications, obvious signs e.g. jaundice, cyanosis, O2 mask, or chest dyspnea). 1 tube(look at the lateral sides of chest wall), metered dose inhalers, and the presence of a sputum mug. 2 Body built: normal, thin, or obese The patient looks comfortable and he doesn't appear short of breath and he doesn't obviously use accessory muscles or any heard Connections: such as nasal cannula wheezes. To determine this, check for: (mention the medications), nasogastric Dyspnea: Assess the rate, depth, and regularity of the patient's 3 tube, oxygen mask, canals or nebulizer, breathing by counting the respiratory rate, range (16–25 breaths Holter monitor, I.V. -

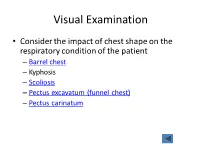

Visual Examination

Visual Examination • Consider the impact of chest shape on the respiratory condition of the patient – Barrel chest – Kyphosis – Scoliosis – Pectus excavatum (funnel chest) – Pectus carinatum Visual Assessment of Thorax • Thoracic scars from previous surgery • Chest symmetry • Use of accessory muscles • Bruising • In drawing of ribs • Flail segment www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm0904437 • Paradoxical breathing /seesaw breathing • Pursed lip breathing • Nasal flaring Palpation • For vibration of secretion • Surgical emphysema • Symmetry of chest movement • Tactile vocal fremitus • Check for a tracheal tug • Palpate Nodes http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK368/ https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=uzgdaJCf0Mk Auscultation • Is there any air entry? • Differentiate – Normal vesicular sounds – Bronchial breathing – Wheeze – Distinguish crackles • Fine • Coarse • During inspiration or expiration • Profuse or scanty – Absent sounds – Vocal resonance http://www.easyauscultation.com/lung-sounds.aspx Percussion • Tapping of the middle phalanx of the left middle finger with the right middle finger • Sounds should be resonant but may be – Hyper resonant – Dull – Stony Dull http://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/the25/pulmonary.html Pathological Expansion Mediastinal Percussion Breath Further Process Displacement Note Sounds Examination Consolidation Reduced on None Dull Bronchial affected side breathing Vocal resonance Whispering pectoriloquy Collapse Reduced on Towards Dull Reduced None affected side affected side Pleural Reduced on Towards Stony dull Reduced/ Occasional rub effusion affected side opposite side Absent Empyema Asthma Reduced None Resonant Normal/ Wheeze throughout Reduced COPD Reduced None Resonant/ Normal/ Wheeze throughout Hyper-resonant Reduced Pulmonary Normal or None Normal Normal Bibasal crepitations Fibrosis reduced throughout Pneumothorax Reduced on Towards Hyper-resonant Reduced/ None affected side opposite side Absent http://www.cram.com/flashcards/test/lung-sounds-886428 sign up and test yourself.. -

Age-Related Pulmonary Crackles (Rales) in Asymptomatic Cardiovascular Patients

Age-Related Pulmonary Crackles (Rales) in Asymptomatic Cardiovascular Patients 1 Hajime Kataoka, MD ABSTRACT 2 Osamu Matsuno, MD PURPOSE The presence of age-related pulmonary crackles (rales) might interfere 1Division of Internal Medicine, with a physician’s clinical management of patients with suspected heart failure. Nishida Hospital, Oita, Japan We examined the characteristics of pulmonary crackles among patients with stage A cardiovascular disease (American College of Cardiology/American Heart 2Division of Respiratory Disease, Oita University Hospital, Oita, Japan Association heart failure staging criteria), stratifi ed by decade, because little is known about these issues in such patients at high risk for congestive heart failure who have no structural heart disease or acute heart failure symptoms. METHODS After exclusion of comorbid pulmonary and other critical diseases, 274 participants, in whom the heart was structurally (based on Doppler echocar- diography) and functionally (B-type natriuretic peptide <80 pg/mL) normal and the lung (X-ray evaluation) was normal, were eligible for the analysis. RESULTS There was a signifi cant difference in the prevalence of crackles among patients in the low (45-64 years; n = 97; 11%; 95% CI, 5%-18%), medium (65-79 years; n = 121; 34%; 95% CI, 27%-40%), and high (80-95 years; n = 56; 70%; 95% CI, 58%-82%) age-groups (P <.001). The risk for audible crackles increased approximately threefold every 10 years after 45 years of age. During a mean fol- low-up of 11 ± 2.3 months (n = 255), the short-term (≤3 months) reproducibility of crackles was 87%. The occurrence of cardiopulmonary disease during follow-up included cardiovascular disease in 5 patients and pulmonary disease in 6. -

Anatomical Variants in the Termination of the Cephalic Vein Stoyan Novakov1*, Elena Krasteva2

Institute of Experimental Morphology, Pathology and Anthropology with Museum Bulgarian Anatomical Society Acta morphologica et anthropologica, 25 (3-4) Sofia • 2018 Anatomical Variants in the Termination of the Cephalic Vein Stoyan Novakov1*, Elena Krasteva2 1 Department of Anatomy, Histology and Embryology, 2Department of Propaedeutics of Surgical Di- seases, Medical Faculty, Medical University of Plovdiv * Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Jugulocephalic vein is atavistic structure which is very rare. The low incidence of the variations of the cephalic vein in deltopectoral triangle and its position on the anterior surface of the clavicle and the neck doesn’t make it less important for the clinical practice. Phylo- and ontogenesis explain the formation of the above mentioned variations. We followed the pattern of the cephalic vein in its proximal part and termination to describe possible variations. In this long term study on 140 upper limbs of 70 cadavers, 4 or 2,9% of the cephalic veins were variable. The direct empting of the cephalic vein into internal jugular is an exception with few descriptions at the moment. The rareness of this anatomical variation doesn’t make it less important for clinical practice. It is described as a possible obstacle in catheter implantation, clavicle fractures and creation of arteriovenous fistula in patients on hemodialysis. Key words:cadavers, human anatomy variation, cephalic vein, external jugular vein, jugulocephalic vein Introduction Cephalic vein (CV) belongs to the group of superficial veins of the upper limb. It usually forms over the anatomical snuff-box on the radial side of the wrist from the radial end of the dorsal venous plexus. -

A Pocket Manual of Percussion And

r — TC‘ B - •' ■ C T A POCKET MANUAL OF PERCUSSION | AUSCULTATION FOB PHYSICIANS AND STUDENTS. TRANSLATED FROM THE SECOND GERMAN EDITION J. O. HIRSCHFELDER. San Fbancisco: A. L. BANCROFT & COMPANY, PUBLISHEBS, BOOKSELLEBS & STATIONEB3. 1873. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, By A. L. BANCROFT & COMPANY, Iii the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. TRAN jLATOR’S PREFACE. However numerou- the works that have been previously published in the Fi 'lish language on the subject of Per- cussion and Auscultation, there has ever existed a lack of a complete yet concise manual, suitable for the pocket. The translation of this work, which is extensively used in the Universities of Germany, is intended to supply this want, and it is hoped will prove a valuable companion to the careful student and practitioner. J. 0. H. San Francisco, November, 1872. PERCUSSION. For the practice of percussion we employ a pleximeter, or a finger, upon which we strike with a hammer, or a finger, producing a sound, the character of which varies according to the condition of the organs lying underneath the spot percussed. In order to determine the extent of the sound produced, we may imagine the following lines to be drawr n upon the chest: (1) the mammary line, which begins at the union of the inner and middle third of the clavicle, and extends downwards through the nipple; (2) the paraster- nal line, which extends midway between the sternum and nipple ; (3) the axillary line, which extends from the centre of the axilla to the end of the 11th rib. -

Chest Mobilization Techniques for Improving Ventilation and Gas Exchange in Chronic Lung Disease

We are IntechOpen, the world’s leading publisher of Open Access books Built by scientists, for scientists 5,400 133,000 165M Open access books available International authors and editors Downloads Our authors are among the 154 TOP 1% 12.2% Countries delivered to most cited scientists Contributors from top 500 universities Selection of our books indexed in the Book Citation Index in Web of Science™ Core Collection (BKCI) Interested in publishing with us? Contact [email protected] Numbers displayed above are based on latest data collected. For more information visit www.intechopen.com 20 Chest Mobilization Techniques for Improving Ventilation and Gas Exchange in Chronic Lung Disease Donrawee Leelarungrayub Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University Thailand 1. Introduction The clinical treatment and rehabilitation of chronic lung disease such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is very challenging, as the chronic and irreversible condition of the lung, and poor quality of life, causes great difficulty to the protocol for intervention or rehabilitation. Most of the problems are, for example, air trapping and destroyed parenchymal lung, which cause chest wall abnormalities and respiratory muscle dysfunction that relate to dyspnea and decreased exercise tolerance (ATS/ERS 2006). Many intergrated problems such as increased airflow resistance, impaired central drive, hypoxemia, or hyperinflation result in respiratory muscle dysfunction, for instance, lack of strength, low endurance level, and early fatigue. Lung hyperinflation in COPD increases the volume of air remaining in the lung and reduces elastic recoil, thus giving rise to air trapping, which results in alveolar hypoventilation (Ferguson 2006). -

Infraclavicular Topography of the Brachial Plexus Fascicles in Different Upper Limb Positions

Int. J. Morphol., 34(3):1063-1068, 2016. Infraclavicular Topography of the Brachial Plexus Fascicles in Different Upper Limb Positions Topografía Infraclavicular de los Fascículos del Plexo Braquial en Diferentes Posiciones del Miembro Superior Daniel Alves dos Santos*; Amilton Iatecola*; Cesar Adriano Dias Vecina*; Eduardo Jose Caldeira**; Ricardo Noboro Isayama**; Erivelto Luis Chacon**; Marianna Carla Alves**; Evanisi Teresa Palomari***; Maria Jose Salete Viotto**** & Marcelo Rodrigues da Cunha*,** ALVES DOS SANTOS, D.; IATECOLA, A.; DIAS VECINA, C. A.; CALDEIRA, E. J.; NOBORO ISAYAMA, R.; CHACON, E. L.; ALVES, M. C.; PALOMARI, E. T.; SALETE VIOTTO, M. J. & RODRIGUES DA CUNHA, M. Infraclavicular topography of the brachial plexus fascicles in different upper limb positions. Int. J. Morphol., 34 (3):1063-1068, 2016. SUMMARY: Brachial plexus neuropathies are common complaints among patients seen at orthopedic clinics. The causes range from traumatic to occupational factors and symptoms include paresthesia, paresis, and functional disability of the upper limb. Treatment can be surgical or conservative, but detailed knowledge of the brachial plexus is required in both cases to avoid iatrogenic injuries and to facilitate anesthetic block, preventing possible vascular punctures. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the topography of the infraclavicular brachial plexus fascicles in different upper limb positions adopted during some clinical procedures. A formalin- preserved, adult, male cadaver was used. The infraclavicular and axillary regions were dissected and the distance of the brachial plexus fascicles from adjacent bone structures was measured. No anatomical variation in the formation of the brachial plexus was observed. The metric relationships between the brachial plexus and adjacent bone prominences differed depending on the degree of shoulder abduction. -

Pleurisy Dry and Exudative: Symptoms and Syndromes Based on Clinical-Instrumental and Laboratory Methods of Study

Topic: Pleurisy dry and exudative: symptoms and syndromes based on clinical-instrumental and laboratory methods of study. Syndrome of fluid and air accumulation in the pleural cavity in pathology of the respiratory system Objective 1. Patient S. 25 years old, has complaints of severe pain in the left half of the chest, exacerbated by deep breath, lack of air. He first felt sick 3 days ago, noticed a one-time increase in body temperature to 37,5°C. On examination: rapid superficial breathing, the left half of the chest is slower in the act of breathing. Clear pulmonary sound is determined by percussion. During auscultation, there is a pleural friction sound to the left, it is louder in the armpit. The pain increases with inhalation, decreases with lying on the side of pain. In the general clinical blood test - moderate leukocytosis, ESR - 17 mm / h. Questions: 1. What is the diagnosis? 2. What (all) data will the doctor receive when auscultating the patient's lungs with this pathology? 3. How can you distinguish the pleural friction sound from the pericardial friction sound? 4. What is the normal respiratory rate? What is the respiratory rate of rapid breathing? 5. What are the possible causes of this disease. Task 2. Patient M., 33 years old, has complaints of chills, fever up to 38,5°C for 3 days, dry cough, pain in the right half of the chest. The pain is exacerbated by breathing and coughing. Objectively: the skin is pale, the lips are cyanotic, the respiratory rate is up to 30 per minute, the right half of the chest is enlarged in volume, the intercostal spaces are smoothed. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists.