PHILLIP PENDAL B.1947 – D.2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mr Peter Katsambanis; Dr David Honey; Mr Peter Rundle; Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Dean Nalder; Mr Zak Kirkup

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 16 April 2020] p2273b-2298a Mr John Quigley; Mr Peter Katsambanis; Dr David Honey; Mr Peter Rundle; Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Dean Nalder; Mr Zak Kirkup COMMERCIAL TENANCIES (COVID-19 RESPONSE) BILL 2020 Introduction and First Reading Bill introduced, on motion by Mr J.R. Quigley (Minister for Commerce), and read a first time. Explanatory memorandum presented by the minister. Second Reading MR J.R. QUIGLEY (Butler — Minister for Commerce) [6.52 pm]: I move — That the bill be now read a second time. The bill I am introducing today is essential to support the continuity of commercial tenancies, during what is likely to be a period of significant social and economic upheaval for all Western Australians. The social and economic health and wellbeing of Western Australians is the government’s highest priority as we face the significant challenges presented to us by the spread of COVID-19. On 29 March 2020, the national cabinet announced that a moratorium on evictions for non-payment of rent would be applied across commercial tenancies impacted by financial distress due to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. On 3 April 2020, the national cabinet announced a set of common principles to provide protections and relief for tenants in relation to commercial tenancies, and on 7 April 2020, it endorsed the mandatory code of conduct, the National Cabinet Mandatory Code of Conduct for SME Commercial Leasing Principles during COVID-19, aimed at mitigating and limiting the hardship suffered by the community as a result of the spread of COVID-19 in our state and across the nation. -

P982c-988A Dr David Honey; Mrs Michelle Roberts; Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Shane Love

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 20 February 2020] p982c-988a Dr David Honey; Mrs Michelle Roberts; Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Shane Love MINISTER FOR TRANSPORT — ALLEGATIONS AGAINST MEMBER FOR RIVERTON Standing Orders Suspension — Motion DR D.J. HONEY (Cottesloe) [4.27 pm]: — without notice: I move — That so much of standing orders be suspended as is necessary to enable the following motion to be moved forthwith — That this house requires the Minister for Transport to table evidence of an allegation of bullying and intimidation by the member for Riverton toward the Mayor of Nedlands, given that he did not speak to the mayor at the event in question; and, if she cannot, the house will require her to immediately apologise for defaming the member for Riverton and misleading the Parliament of Western Australia. I understand that the acting Leader of the House has agreed to this and has agreed on times for the motion. Standing Orders Suspension — Amendment to Motion MRS M.H. ROBERTS (Midland — Minister for Police) [4.27 pm]: Although I do not believe that there is any substance to the motion, we are prepared to hear what the opposition has to say. I move — To insert after “forthwith” — , subject to the debate being limited to 10 minutes for government members and 10 minutes for non-government members Amendment put and passed. Standing Orders Suspension — Motion, as Amended The ACTING SPEAKER (Mr T.J. Healy): As this is a motion without notice to suspend standing orders, it will need an absolute majority in order to succeed. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright Land Rich, Dirt Poor? Aboriginal land rights, policy failure and policy change from the colonial era to the Northern Territory Intervention Diana Perche A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2015 Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. -

Parliamentary Handbook the Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Twenty-Fourth Edition Twenty-Fourth Edition

The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Parliamentary Australian Western The The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Twenty-Fourth Edition Twenty-Fourth Twenty-Fourth Edition David Black The Western Australian PARLIAMENTARY HANDBOOK TWENTY-FOURTH EDITION DAVID BLACK (editor) www.parliament.wa.gov.au Parliament of Western Australia First edition 1922 Second edition 1927 Third edition 1937 Fourth edition 1944 Fifth edition 1947 Sixth edition 1950 Seventh edition 1953 Eighth edition 1956 Ninth edition 1959 Tenth edition 1963 Eleventh edition 1965 Twelfth edition 1968 Thirteenth edition 1971 Fourteenth edition 1974 Fifteenth edition 1977 Sixteenth edition 1980 Seventeenth edition 1984 Centenary edition (Revised) 1990 Supplement to the Centenary Edition 1994 Nineteenth edition (Revised) 1998 Twentieth edition (Revised) 2002 Twenty-first edition (Revised) 2005 Twenty-second edition (Revised) 2009 Twenty-third edition (Revised) 2013 Twenty-fourth edition (Revised) 2018 ISBN - 978-1-925724-15-8 The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook The 24th Edition iv The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook The 24th Edition PREFACE As an integral part of the Western Australian parliamentary history collection, the 24th edition of the Parliamentary Handbook is impressive in its level of detail and easy reference for anyone interested in the Parliament of Western Australia and the development of parliamentary democracy in this State since 1832. The first edition of the Parliamentary Handbook was published in 1922 and together the succeeding volumes represent one of the best historical record of any Parliament in Australia. In this edition a significant restructure of the Handbook has taken place in an effort to improve usability for the reader. The staff of both Houses of Parliament have done an enormous amount of work to restructure this volume for easier reference which has resulted in a more accurate, reliable and internally consistent body of work. -

An Ethnography of Health Promotion with Indigenous Australians in South East Queensland

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292140373 "We don't tell people what to do": An ethnography of health promotion with Indigenous Australians in South East Queensland Thesis · December 2015 CITATIONS READS 0 36 1 author: Karen McPhail-Bell University of Sydney 25 PUBLICATIONS 14 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Karen McPhail-Bell Retrieved on: 25 October 2016 “We don’t tell people what to do” An ethnography of health promotion with Indigenous Australians in South East Queensland Karen McPhail-Bell Bachelor of Behavioural Science, Honours (Public Health) Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Public Health and Social Work Queensland University of Technology 2015 Key words Aboriginal, Aboriginal Medical Service, Australia, colonisation, community controlled health service, critical race theory, cultural interface, culture, ethnography, Facebook, government, health promotion, identity, Indigenous, Instagram, mainstream, policy, postcolonial theory, public health, relationship, self- determination, social media, Torres Strait Islander, Twitter, urban, YouTube. ii Abstract Australia is a world-leader in health promotion, consistently ranking in the best performing group of countries for healthy life expectancy and health expenditure per person. However, these successes have largely failed to translate into Indigenous health outcomes. Given the continued dominance of a colonial imagination, little research exists that values Indigenous perspectives, knowledges and practice in health promotion. This thesis contributes to addressing this knowledge gap. An ethnographic study of health promotion practice was undertaken within an Indigenous-led health promotion team, to learn how practitioners negotiated tensions of daily practice. -

Julie Bishop and Malcolm Turnbull Took to Twitter to Deny Ben Fordham’S Claims They Had Secret Meeting in Sydney

Julie Bishop and Malcolm Turnbull took to Twitter to deny Ben Fordham’s claims they had secret meeting in Sydney DAVID MEDDOWS THE DAILY TELEGRAPH FEBRUARY 05, 2015 4:29PM Malcolm Turnbull and Julie Bishop have taken to social media to deny they had planned a secret meeting in Sydney today. Picture: Supplied THE political rumour mill went into overdrive today when a Sydney radio host suggested Julie Bishop and Malcolm Turnbull had arranged a secret meeting in Sydney. 2GB host Fordham took to Twitter this afternoon claiming that Bishop and Turnbull would be meeting at the Communication Minister’s house sometime today. “Interesting fact - @JulieBishopMP and @TurnbullMalcolm have arranged to meet at his Sydney home today,” the Tweet read. But the pair quickly fired back denying the claims. The Communications Minister even provided happy snaps to prove his whereabouts. “you need to improve yr surveillance! I am on the train to Tuggerah. PoliticsinPub Nth Wyong 2nite,” wrote. “No Ben. At 11.30 am I was not meeting w @JulieBishopMP - after a meeting at NBNCo I was waiting for a train at Nth Sydney,” he said. Mr Turnbull was heading to the Central Coast where he was meeting with local MP Karen McNamara. Just to prove his point he posted pictures from the train trip and one hugging a sign at Tuggerah station. “Arrived at our destination! @BenFordham looking forward to discussing broadband with Karen Mcnamara MP,” he said. Still not convinced, Fordham asked one more time for confirmation from Mr Turnbull. “At the risk of coming across as obsessed, can I kindly ask you confirm you did not meet Julie today? *ducks rotten fruit*” he asked on Twitter. -

Malcolm Turnbull's Plotters Find Political Success Elusive

Malcolm Turnbull's plotters find political success elusive AFR, Aaron Patrick, 22 Aug 2017 Mal Brough vanished. Wyatt Roy sells call centre technology. Peter Hendy wants a Senate seat. James McGrath is in ministerial limbo land. Arthur Sinodinos stays quiet. Scott Ryan is struck out sick. Simon Birmingham is at war with the Catholic Church. Mitch Fifield tried to buy media peace from One Nation. They have been dubbed the G8: the eight Liberals most intimately involved in the successful plot to remove Tony Abbott as prime minister. When they installed Malcolm Turnbull party leader on September 14, 2015, all might have seen their political careers flourishing under what many people expected at the time to be a unifying, inspiring and competent prime minister. Instead, their stories in some ways personify the broader story of the Liberal government: starting with such promise, they have mostly either proved to be disappointments or failed to live up to their early promise. An opinion poll published Monday shows the Labor Party would easily win power based on current voting preferences. Fateful decision When they gathered on the evening of September 13, 2015, at Hendy's home in Queanbeyan, on the outskirts of Canberra, the atmosphere was thick with anticipation. The group, excluding Birmingham, who was flying up from Adelaide, took the fateful decision to remove a first-term leader who had ended six years of Labor power. The next day, Roy, Hendy, Brough, Ryan, Sinodinos and Fifield walked briskly alongside Turnbull to the meeting in Parliament House where they brought down Abbott, triggering open conflict between the two main wings of the party that persists today. -

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee —Supplementary Budget Estimates Hearing—October 2015 Answers to Questions on Notice Parliamentary departments, Department of Parliamentary Services Topic: Cost of Ministerial movements Question: 15 Hansard Reference p 19, 24; 19 October 2015 Date set by the committee for the return of answer: 4 December 2015 Senator WONG: I presume, because you are all assiduous preparers, that people are aware to my questions to the Department of the Senate about the moves associated with the change to the ministry and the Prime Minister. Dr Heriot: Yes. Senator WONG: What information can you give me on that—the costs and what occurred? Dr Heriot: While Mr Ryan is taking his seat at the front, I can tell you that I am advised that there were seven moves of senators, 23 moves of members and 23 moves in the ministry associated with the appointment of a new Prime Minister and his cabinet. We undertake, as suite changes happen, wherever possible routine maintenance, including patching, painting and other minor repairs as necessary. We also have responsibility for changing glass plaque signages as people change their official positions, and I understand that we have done a number of those that I just mentioned as associated with the move. We have done paint and patch repairs. Because they are done by our staff, I am afraid I do not have a cost for you. I can take that on notice as a hypothetical cost. … Senator WONG: Okay. What about the cost of moving—the actual relocation itself, with boxes and a contractor to carry them? How is that managed? Do I wait for Mr Ryan to come back? Dr Heriot: I understand that we do not bear those costs, but I will get confirmation when Mr Ryan is back. -

List of Members, Vol 25

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members Forty Fourth Parliament Volume 25 - 10 August 2015 Name Electorate & Party Electorate office address, telephone and facsimile Parliament House State / Territory numbers & other office details where applicable telephone & facsimile numbers Abbott, The Hon Anthony John Warringah, LP Level 2, 17 Sydney Road (PO Box 450), Manly Tel: (02) 6277 7700 (Tony) NSW NSW 2095 Fax: (02) 6273 4100 Prime Minister Tel : (02) 9977 6411, Fax : (02) 9977 8715 Albanese, The Hon Anthony Grayndler, ALP 334A Marrickville Road, Marrickville NSW 2204 Tel: (02) 6277 4664 Norman NSW Tel : (02) 9564 3588, Fax : (02) 9564 1734 Fax: (02) 6277 8532 E-mail: [email protected] Alexander, Mr John Gilbert Bennelong, LP Suite 1, 44 - 46 Oxford St (PO Box 872), Epping Tel: (02) 6277 4804 OAM NSW NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 Tel : (02) 9869 4288, Fax : (02) 9869 4833 E-mail: [email protected] Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LP Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive (PO Box 409), Tel: (02) 6277 4360 Parliamentary Secretary to the Qld Varsity Lakes Qld 4227 Fax: (02) 6277 8462 Minister for Industry and Science Tel : (07) 5580 9111, Fax : (07) 5580 9700 E-mail: [email protected] Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road (PO Box 124), Tel: (02) 6277 7800 Minister for Defence Vic Doncaster Vic 3108 Fax: (02) 6273 4118 Tel : (03) 9848 9900, Fax : (03) 9848 2741 E-mail: [email protected] Baldwin, The Hon Robert Charles Paterson, -

Reconciliation Across Law and Culture

THE NORTHERN TERRITORY EMERGENCY RESPONSE 905 THE NORTHERN TERRITORY EMERGENCY RESPONSE: THE MORE THINGS CHANGE, THE MORE THEY STAY THE SAME NICOLE WATSON* The Northern Territory Emergency Response Le Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) (NTER) was a raft of measures introduced by the était un ensemble de mesures introduites par le Commonwealth of Australia in response to allegations Commonwealth de l’Australie après des allégations de of child sexual abuse in Northern Territory Aboriginal violence sexuelle à l’endroit des enfants des communities. The measures included the compulsory communautés autochtones des territoires. Les mesures acquisition of Aboriginal lands, the quarantining of incluaient l’obligation d’acquérir des terres welfare payments, prohibitions on alcohol, and the autochtones, la mise en quarantaine des prestations de vesting of expansive powers in the Commonwealth bien-être social, l’interdiction d’alcool et Minister to intervene in the affairs of Aboriginal l’investissement de pouvoirs plus vastes au ministère organizations. This article aims to provide a brief du Commonwealth pour intervenir dans les affaires historical background of Aboriginal people’s des organisations autochtones. Cet article vise à experiences with the law in Australia, discuss certain donner le contexte historique des expériences des provisions of the NTER, and, finally, examine the peuples autochtones avec la loi en Australie, de consequences three years after the implementation of discuter de certaines dispositions du NTER et enfin the NTER. Through this analysis, the author suggests d’examiner les conséquences trois ans après la mise en that history remains a powerful influence, resulting in œuvre du NTER. Au moyen de cette analyse, l’auteur the NTER being based on assumptions of Aboriginal laisse penser que l’histoire demeure une influence people that are grounded in a racist past. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

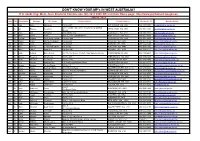

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough