Driving-Miss-Daisy-G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Miss Daisy Flame.Indd

Women’s Health CLINIC FEBRUARY 2014 SEASON | YEAR A NEWSLETTER DEDICATED TO GROUPS, ORGANIZATIONS AND FRIENDS OF THE FIRESIDE THEATRE A Hilarious, Heartwarming Must-See FOR OVER THREE DECADES THE FIRESIDE HAS BEEN KNOWN FOR PRODUCING BIG, BRIGHT MUSICAL COMEDIES AND SPECTACULAR MUSICAL REVUES. MUSICAL THEATRE HAS BEEN MY SPECIALTY AND MY PASSION SINCE I SAW MY FIRST BROADWAY MUSICAL AT AGE 6. I TAKE GREAT PRIDE WHENEVER SOMEONE MARVELS AT HOW WE CAN TAKE A BIG BROADWAY MUSICAL AND PUT IT ON OUR SMALL ARENA STAGE WITHOUT LOSING ANY OF ITS WONDER. MUSICALS HAVE BEEN, WITHOUT A DOUBT, THE MAIN DISH ON THE FIRESIDE’S THEATRICAL MENU SINCE WE FIRST OPENED. Then why is it that one of the most I am very excited about directing our popular shows in Fireside history (as well production of this unforgettable play this as in theatrical history) is a three person spring. I have directed DRIVING MISS play about an elderly white woman, her DAISY twice before – once here and aging African American chauffer, and once in a theatre in Ohio and I can her beleaguered middle aged son told honestly say that of all the wonderful simply without a song or a dance in sight. shows I have directed in my 45+ years Is it because we see ourselves and our as a professional director that no other loved ones in this heart-warming tale? Is play has touched my heart more deeply “ Millions of people rank this it because it is hilariously funny without than DAISY. And I am not alone. -

Calendar No. 238

Calendar No. 238 110TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 1st Session SENATE 110–107 DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES APPROPRIATION BILL, 2008 R E P O R T OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS U.S. SENATE ON S. 1710 JUNE 27, 2007.—Ordered to be printed Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriation Bill, 2008 (S. 1710) Calendar No. 238 110TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 1st Session SENATE 110–107 DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERV- ICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES APPRO- PRIATION BILL, 2008 JUNE 27, 2007.—Ordered to be printed Mr. HARKIN, from the Committee on Appropriations, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany S. 1710] The Committee on Appropriations reports the bill (S. 1710) mak- ing appropriations for Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education and related agencies for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2008, and for other purposes, reports favor- ably thereon and recommends that the bill do pass. Amount of budget authority Total of bill as reported to the Senate ............. $605,536,474,000 Amount of 2007 appropriations ........................ 545,857,321,000 Amount of 2008 budget estimate ...................... 596,378,249,000 Bill as recommended to Senate compared to— 2007 appropriations .................................... ∂59,679,153,000 2008 budget estimate ................................. ∂9,158,225,000 36–285 PDF CONTENTS Page Summary of Budget Estimates and Committee Recommendations ................... -

Driving Miss Daisy – Mother &

Driving Miss Daisy 1 In the dark we hear a car ignition turn on, and then a horrible crash. Bangs and booms and wood splintering. When the noise is very loud, it stops suddenly and the lights come up on Daisy Werthan’s living room, or a portion thereof. Daisy, age 72, is wearing a summer dress and high heeled shoes. Her hair, her clothes, her walk, everything about her suggests bristle and feist and high energy. She appears to be in excellent health. Her son, Boolie Werthan 40, is a businessman, Junior Chamber of Commerce style. He has a strong capable air. The Werthans are Jewish, but they have strong Atlanta accents. DAISY. No! BOOLIE. Mama! DAISY. No! BOOLE. Mama! DAISY. I said no, Boolie, and that’s the end of it. BOOLIE. It’s a miracle you’re not laying in Emory Hospital---- or decked out at the funeral home. Look at you! You didn’t even break your glasses. DAISY. It was the car’s fault. BOOLIE. Mama, the car didn’t just back over the driveway and land on the Pollard’s garage all by itself. You had it in the wrong gear. DAISY. I did not! BOOLIE. You put it in reverse instead of drive. The police report shows that. DAISY. You should have let me keep my La Salle. BOOLIE. Your La Salle was eight years old. DAISY. I don’t care. It never would have behaved this way. And you know it. BOOLIE. Mama, cars, don’t behave. They are behaved upon. The fact is you, all by yourself, demolished that Packard. -

Driving Miss Daisy

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL FOR RESEARCH USE ONLY: MAY NOT BE DUPLICATED 2012.3.75 MAKING OF THE MOVIE DRIVING MISS DAISY (Transcript of television program The Real Miss Daisy, produced by WAGA-TV, Channel 5, Atlanta, and broadcast in 1990 on public television.) ANNOUNCER VOICE-OVER, with animated numeral 5 rotating and coming to a stop in the center of the screen: Your regular PBS programming will not be seen tonight so that we may bring you the following special program. ANNOUNCER VOICE-OVER: This program is presented as part of WAGA-TV’s year-long project, A World of Difference, in cooperation with the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai Brith and underwritten by Georgia Power Company and the Milken Foundation. ANNOUNCER VOICE-OVER, with title displayed onscreen: The Real Miss Daisy, brought to you by True Value Hardware, your store of first choice. ANNOUNCER (LISA CLARK) VOICE-OVER, with still shot of the three principal actors in Driving Miss Daisy: Dan Aykroyd, Jessica Tandy, and Morgan Freeman: This is the story about the story of three people and the world in which they lived. Screen changes from actors’ photograph to video of three presenters, WAGA-TV journalists: Jim Kaiserski on left, Lisa Clark in center, Ken Watts on right, standing next to vintage black Cadillac [the same one used in the film?] in front of WAGA-TV studios in Atlanta. JIM KAISERSKI: It’s a story about people, it’s a story about places, it’s a story about events that were real and some that weren’t. KEN WATTS: But reality isn’t the important point; truth is. -

AUDIENCE INSIGHTS the Story Oftoulouse-Lautrec a Newmusical TABLE of CONTENTS

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS the story oftoulouse-lautrec A NewMusical TABLE OF CONTENTS MY PARIS Character Summary & Show Synopsis.........................................................................................3 The Norma Terris Theatre July 23 - Aug 16, 2015 Meet the Writers...................................................................................................................................4 _________ Director’s Vision....................................................................................................................................7 Music and Lyrics by CHARLES AZNAVOUR Author’s Notes.......................................................................................................................................8 Book by “Goodspeed to Produce...” Excerpt from The Day.....................................................................9 ALFRED UHRY Toulouse-Lautrec: Balancing Two Worlds.................................................................................10 English Lyrics and His Paris.................................................................................................................................................12 Musical Adaptation by JASON ROBERT BROWN Impressionist Impressions.............................................................................................................13 Resources......................................................................................................................14 Lighting Design by DON HOLDER Costume Design -

?Mg HI JAV 13 Compensation of Officers, Directors, Trustees, Etc 14 Other Employee Salaries and Wages

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury ► X015 Internal Revenue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. • ' ?I ITPT-M trM For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning , 2015, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number Monsanto Fund 43-6044736 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 800 North Lindbergh Blvd. 314-694-4391 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code q C If exemption application is ► pending , check here. St. Louis, MO 63167 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organizations , check here . ► El Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the Address change Name change 85% test , check here and attach computation , , . ► H Check type of organization X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E It private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation 0 under section 507(b )(1)(A), check here . ► I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method X Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination q end of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other (specify) under section 507(b )( 1)(B), check here . -

10 Years of Lave & Shows

Outline of the LAVE (Life And Values Education) PROGRAMS developed for NCSY by Rabbi Dr. N. Amsel (2002) Below is the outline of the NCSY LAVE Programs. Each lesson consists of a description of the video, goals of the lesson, a step-by-step Q&A and sources in English and Hebrew. For more information about this program, contact Rabbi Nachum Amsel TOPIC TRIGGER VIDEO YEAR I 1. Relationship to Elders and Sensitivity to All Others The Shopping Bag Lady 2. Choices and Priorities in Judaism The Bill Cosby Show 3. Tzedaka, Chesed and Charity: What’s the Difference? Clown 4. Prejudice By and Against Jews Barney Miller 5. Business Ethics and Stealing Archie Bunker: Brings home drill 6. Personal Antisemitism and the Jewish Reaction Archie Bunker: JDL YEAR II 1. Jewish Identity Archie Bunker: Stephanie’s Jewish 2. Snitching: Right or Wrong? One Day At a Time 3. Jewish Prayer and Self-Actualization Taxi 4. Shul Vandalism: The New Antisemitism? Archie Bunker 5. Lashon Hara and the Jewish Concept of Speech Facts of Life YEAR III 1. Israel and Jewish Identity (Double Lesson) Cast a Giant Shadow: (First scene) 2. Cheating and Honesty Better Days 3. Death and Shiva in Judaism Facts of Life 4. The Jewish Attitude to Wealth and Money Twilight Zone 5. Understanding the Palestinian Uprising 48 Hours: (20 minute clip) 6. Being Different and Being Jewish Molly's Pilgrim YEAR IV 1. The Jewish Attitude to Senility Grandma Never Waved Back 2-3. Bad Things Happen to Good People: Some Jewish Approaches Webster 4. Jewish Attitudes to the Mentally Handicapped Kate and Allie 5. -

ASF 2015 Study Materials for by Alfred Uhry

ASF 2015 Study Materials for Welcome to 1947 1972 1876 Driving Miss Daisy by Alfred Uhry Director John Manfredi Study Materials written by Susan Willis Set Design John Manfredi ASF Dramaturg Costume Design Elizabeth Novak [email protected] Lighting Design Tom Rodman Contact ASF: 1.800.841-4273, www.asf.net ASF/ 1 Driving Miss Daisy by Alfred Uhry Welcome—Let's Take A Drive Together Alfred Uhry is almost as good a chauffeur as Hoke Coleburn. He transports us not only through the span of 25 years in the lives of three characters but also through the transformation of an entire era in the South. He negotiates Characters these changes with smooth, effortless turns, with Daisy Werthan, a widow aged pungent, realistic dialogue, and with detailed 72 to 97 during play character development. To be subject to Uhry’s Boolie Werthan, her son, aged dramatic drive is pure pleasure. 40 to 65 during play Driving Miss Daisy is a memory play, almost Hoke Coleburn, Miss Daisy's a scrapbook of moments. In it Uhry depicts a chauffeur, aged 60 to 85 world he knows well, the world of Atlanta and during play the Reform Jewish community he grew up in, Uhry on the Play and the South the world that shaped him and which he has “I thought somebody should tell what the Setting: Atlanta, Georgia, evoked in shaping this play. Uhry not only creates South was really like,” Alfred Uhry claims as he between 1948 and 1973, memorable onstage characters, but intriguing describes his impetus for writing the play: and on Alabama highways offstage characters as well, for who does not I was tired of all these stereotypes—that white to Mobile enjoy imagining Boolie’s wife Florine or Idella people were running around being openly with her fabled coffee? hostile and rude toward black people, and The strength of Uhry's story, as he realizes, that black people were standing there with is what he calls its truth. -

October 2019

October 2019 Hazelton Place Retirement Residence - Independent Calendar Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday ACTIVE AGING WEEK (AAW) OCT Carefirst Exercises Outings Day Carefirst Exercises 10:00 Energizing 1-7th 1 10:00 Computer Training- How 2 SMOOTHIE BREAKFAST- Ask for 3 9:30 RR Ping Pong 4 Exercises [MR] 5 Outings Day Shop on the Internet one! 10:00 Ink Art [AS] 10:45 Go4Life Walking Club 11:00 Hand Therapy [AS] 10:00 Energizing Exercises [MR] 9:30 Outing- Dufferin Mall (SU) 11:15 Sing-Along [P] 1:30 AAW Musical Brain Fun Falls Prevention 10:30 Java Music Club [MT] 11:45 10:00 Energizing Exercises [MR] 11:45 Falls Prevention [MR] 1:30 AAW- Wellness Wednesday [MR] [MR] 10:30 OUTING- Stratford Festival – Billy 10:30 Java Music Club [MT] 1:30 Tennis Club - Balloon Elliot the Musical (Su) 2:00 AAW- What the Health? 2:00 Movie Matinee - One Flew 10:30 Yoga with Karusia [MR] Badminton [MR] 10:30 Tai Chi with Eti [MR] Documentary [MT] 11:00 Outing- Loblaws (SU) Over the Cuckoo's Nest 2:00 AAW- Supersize Me! 11:15 Go4Life Walking Club 2:15 Community Brain Gym [MR] 11:15 Go4Life Walking Club (1975) [MT] Documentary [MT] 1:30 AAW- Classical Stretch and 3:00 Afternoon Tea Social [LL] 11:30 AAW- How to Walk with a Walker 2:15 Watercolours [AS] 2:15 Life Stories Social [STG] Breathing [MR] 3:00 Ecumenical Communion [STG] by Karusia [MR] 3:00 AAW Physical and Mental 3:00 AAW- Classical Stretch and 2:00 Chair Volleyball [MR] 4:00 Ideas Exchange - My Recent Trip 1:30 Word Categories with Gerry [MT] Health Trivia [MR] 2:00 Poetry Club [MT] Around Great Slave Lake, NWT Meet Me at the MoMA Breathing [MR] 2:00 3:00 Afternoon Tea Social [LL] 3:00 Afternoon Tea Social [LL] by Mary Lyon [MT] Discussion- A.Y. -

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo Chapter 1 Introduction This book is the result of research conducted for an exhibition on Louisiana history prepared by the Louisiana State Museum and presented within the walls of the historic Spanish Cabildo, constructed in the 1790s. All the words written for the exhibition script would not fit on those walls, however, so these pages augment that text. The exhibition presents a chronological and thematic view of Louisiana history from early contact between American Indians and Europeans through the era of Reconstruction. One of the main themes is the long history of ethnic and racial diversity that shaped Louisiana. Thus, the exhibition—and this book—are heavily social and economic, rather than political, in their subject matter. They incorporate the findings of the "new" social history to examine the everyday lives of "common folk" rather than concentrate solely upon the historical markers of "great white men." In this work I chose a topical, rather than a chronological, approach to Louisiana's history. Each chapter focuses on a particular subject such as recreation and leisure, disease and death, ethnicity and race, or education. In addition, individual chapters look at three major events in Louisiana history: the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Organization by topic allows the reader to peruse the entire work or look in depth only at subjects of special interest. For readers interested in learning even more about a particular topic, a list of additional readings follows each chapter. Before we journey into the social and economic past of Louisiana, let us look briefly at the state's political history. -

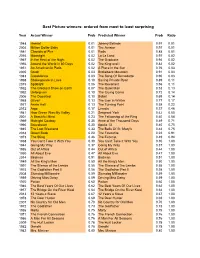

Best Picture Winners: Ordered from Most to Least Surprising

Best Picture winners: ordered from most to least surprising Year Actual Winner Prob Predicted Winner Prob Ratio 1948 Hamlet 0.01 Johnny Belinda 0.97 0.01 2004 Million Dollar Baby 0.01 The Aviator 0.97 0.01 1981 Chariots of Fire 0.01 Reds 0.88 0.01 2016 Moonlight 0.02 La La Land 0.97 0.02 1967 In the Heat of the Night 0.02 The Graduate 0.94 0.02 1956 Around the World in 80 Days 0.02 The King and I 0.82 0.02 1951 An American in Paris 0.02 A Place in the Sun 0.76 0.03 2005 Crash 0.03 Brokeback Mountain 0.91 0.03 1943 Casablanca 0.03 The Song Of Bernadette 0.90 0.03 1998 Shakespeare in Love 0.10 Saving Private Ryan 0.89 0.11 2015 Spotlight 0.06 The Revenant 0.56 0.11 1952 The Greatest Show on Earth 0.07 The Quiet Man 0.53 0.13 1992 Unforgiven 0.10 The Crying Game 0.72 0.14 2006 The Departed 0.10 Babel 0.69 0.14 1968 Oliver! 0.13 The Lion in Winter 0.77 0.17 1977 Annie Hall 0.13 The Turning Point 0.58 0.22 2012 Argo 0.17 Lincoln 0.37 0.46 1941 How Green Was My Valley 0.21 Sergeant York 0.42 0.50 2001 A Beautiful Mind 0.23 The Fellowship of the Ring 0.40 0.58 1969 Midnight Cowboy 0.35 Anne of the Thousand Days 0.49 0.71 1995 Braveheart 0.30 Apollo 13 0.40 0.75 1945 The Lost Weekend 0.33 The Bells Of St. -

A Jewish Day School Surfing the Edge: an Autoethnographic Study

1 A JEWISH DAY SCHOOL SURFING THE EDGE: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY A Doctoral Thesis presented by Sharon Pollin to The School of Education In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education In the field of Education College of Professional Studies Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts February 2017 2 Abstract A thriving Jewish day school is a vital cornerstone of a flourishing Jewish community. Particularly in communities with small Jewish populations, Jewish day schools are able to play roles that extend beyond the lives of their own student body, and they often serve as a hub for community connection and engagement. In July 2013, with a student enrollment of 27, a nationally recognized day school feasibility expert recommended that the Community Day School of New Orleans close its doors. The research problem I intend to study is my experience as leader of the K–5 (renamed) Jewish Community Day School of Greater New Orleans, as it endeavors to achieve viability and strength. Although many recent studies focus on the sustainability of Jewish day schools, there is a gap in the literature about the journey of a school poised at the edge of the wave between viability and impossibility. This autoethnographic account of my experience will contribute to the growing body of scholarly literature on Jewish day school sustainability. Complexity leadership theory serves as the theoretical framework for this research project. Keywords: Complexity leadership theory, autoethnography, Jewish day school sustainability, New Orleans 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Rabbi Dr. Karen Reiss Medwed for the persistence of her support and guidance as my professor at Hebrew College and as my doctoral advisor at Northeastern University.