The Scientific Image of Music Theory Author(S): Matthew Brown and Douglas J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1965-1966

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 1966 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation I " STMVINSKY tt.VlOW agon vam 7/re Boston Symphony SCHULLER 7 STUDIES ox THEMES of PAUL KLEE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ERICH lEINSDORf under Leinsdorf Leinsdorf expresses with great power the vivid colors of Schuller's Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Kiee and, in the same album, Stravinsky's ballet music from Agon. Forthe majorsinging roles in Menotti's dramatic cantata, The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi. Leinsdorf astutely selected George London, and Lili Chookasian, of whom the Chicago Daily Tribune has written, "Her voice has the Boston symphony ecich teinsooof / luminous tonal sheath that makes listening luxurious. menotti Also hear Chookasian in this same album, in songs from the death op the Bishop op BRSndlSI Schbnberg's Gurre-Lieder. In Dynagroove sound. Qeonoe ionoon • tilt choolusun s<:b6notec,/ou*«*--l(eoeo. sooq of the wooo-6ove ac^acm rca Victor fa @ The most trusted name in sound ^V V BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH LeinsDORF, Director Joseph Silverstein, Chairman of the Faculty Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Emeritus Louis Speyer, Assistant Director Victor Babin, Chairman of the Tanglewood Institute Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM Contemporary Music Activities Gunther Schuller, Head Roger Sessions, George Rochberg, and Donald Martino, Guest Teachers Paul Zukofsky, Fromm Teaching Fellow James Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Viola C Aliferis, Assistant Administrator The Berkshire Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. -

Martin Brody Education BA, Summa Cum Laude, Phi Beta

Martin Brody Department of Music Wellesley College Wellesley, MA 02281 617-283-2085 [email protected] Education B.A., summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, Amherst College, 1972 M.M. (1975), M.M.A. (1976), D.M.A. (1981), Yale School of Music Additional studies in music theory and analysis with Martin Boykan and Allan Keiler, Brandeis University (1977); Additional studies in electronic music and digital signal processing with Barry Vercoe, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1979) Principal composition teachers: Donald Wheelock, Lewis Spratlan, Yehudi Wyner, Robert Morris, Seymour Shifrin Academic Positions Catherine Mills Davis Professor of Music, Wellesley College (member of faculty since 1979) Visiting Professor of Music at Brandeis University, 1994 Visiting Associate Professor of Music at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1989 Assistant Professor of Music at Bowdoin College, 1978-79 Assistant Professor of Music at Mount Holyoke College, 1977- Other Professional Employment Andrew Heiskell Arts Director, American Academy in Rome, 2007-10 term Executive Director, Thomas J. Watson Foundation, 1987-9 term Honors and Awards Roger Sessions Memorial Fellow in Music, Bogliasco Foundation, 2004 Composer-in-Residence, William Walton Estate, La Mortella, 2004 Fromm Foundation at Harvard, Composer Commission, 2004 Fromm Composer-in-Residence, American Academy in Rome, fall 2001 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, 2000 Pinanski Prize for Excellence in Teaching, Wellesley College, 2000 Commission for Earth Studies from Duncan Theater/MacArthur -

Differentiation of Concurrent Musical Strata Holly Bergeron-Dumaine

Differentiation of Concurrent Musical Strata Holly Bergeron-Dumaine Music Research McGill University, Montreal August, 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Holly Bergeron-Dumaine 2018 i Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... i Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Reviewing prior theorizing of layered musical construction................................. 3 Polytonality in the Francophone sphere ...................................................................................... 3 Rejection of Polytonality in Anglophone Theory ..................................................................... 18 Layered Musical Construction in Recent North-American Music Theory ............................... 24 Towards a Model of Layered Musical Construction ................................................................ 30 Chapter 2: The Differentiation Model ..................................................................................... -

View PDF Document

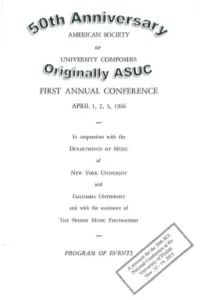

OF UNIVERSITY COMPOSERS @Lr-ii~~lfillfilUUw L~~~@ i.::: FIRST ANNUAL CONFERENCE APRIL 1, 2, 3, 1966 In cooperation with the DEPARTMENTS OF Music of NEW YORK UNIVERSITY and COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY and with the assistance of THE FROMM Musrc FOUNDATION SEMINARS FRIDAY, APRIL 1, 1966 Loeb Student Center, New York University 566 West Broadway (at Washington Square South) New York City I. The University and the Composing Profession: Prospects and Problems 10:00 AM. Room 510 Chairman: Benjamin Boretz New York University Speakers: Grant Beglarian M ttsic Educators' National Confer.mce Andrew Imbrie University of California, Berkeley Iain Hamilton D11ke University Gharles Wuorinen Columbia University II. Computer Performance of Music 2:30 P.M. Room 510 Chairman: J. K. Randall Princeton University Speakers: Herbert Briin University of Illinois Ercolino Ferretti Massachusetts Institflte of Technology James Tenney Yale University Godfrey Winham Princeton University Panel: Lejaren A. Hiller University of Illinois David Lewin University of California, Berkeley Donald Martino Yale University Harold Shapero Brandeis Universi1y FRIDAY, APRIL 1, 1966 CONCERT-DEMONSTRATIONS I By new-music performance groups resident in American universities 8:30 P.M. McMillin Academic Theatre, Columbia University Broadway at 116 Street New York City NOTE: These programs have been chosen by the participating groups them selves as characteristic representations of their work. The Society has exerted no control over the selections made. I. Octandre (1924)-···-·· --···-·····- ·············-··-··-·· ·Edgard Varese (in memoriam) The Group for Contemporary Music at Columbia University Sophie Sollberger, fl11te Josef Marx, oboe Jack Kreiselman, clarinet Alan Brown, bassoon Barry Benjamin, hom Ronald Anderson, trumpet Philip Jameson, trombone Kenneth Fricker, contrabass Charles Wuorinen, cond11ctor II. -

Casca Ndo Realization of Samuel Beckett's Radio Play by Charles I-@---- Dodge Cast of Characters

--*- --*- CASCA NDO REALIZATION OF SAMUEL BECKETT'S RADIO PLAY BY CHARLES I-@---- DODGE CAST OF CHARACTERS Opener john Nesci Voice Computer synthesis based on 1 a reading by Steven Cilborn 1 Music Computer synthesis based on Voice -e 1 Realization made at the computer centers of Columbia University and the City University of New York and the Center for Computer Music at Brooklyn College. CHARLES DODGE but initially withheld rights to public presentation. However, on receiv- Dodge began by composing the basic part for Voice, from start to CASCANDO ing a copy of the finished tape in the spring of 1978, he wrote, "Dear finish. Both rhythm and pitch are notated conventionally, but Separate- Mr. Dodge: Thank you for your letter of April with the tape of your ly. Both were arrived at empirically, not according to any "system." The realization made at the computer centers of Columbia CASCANDO. Okay for public performance." (Dodge finds the "your" rhythms are close to natural speech rhythms. The pitch-successions University and the City University of New York and the Center flattering, and we shall see presently how accurate it is.) are freely chromatic but not twelve-tone; they were chosen, says Dodge, for Computer Music at Brooklyn College There are about as many interpretations of the meaning of Beckett's "to capture the spirit of what I thought the Voice was like." Also, Beckett's drama as there have been interpreters of it. Perhaps the narrative Voice many repetitions of words and phrases-but in many different CHARLES DODGE (b. 1942, Ames, lowa) has long been recognized is that of Opener himself, the former trying desperately to tell the very contexts-were taken into account: "I tried to use the same pitch- as an accomplished composer of computer music. -

Dave Brubeck and Polytonal Jazz Mark Mcfarland

Jazz Perspectives Vol. 3, No. 2, August 2009, pp. 153–176 Dave Brubeck and Polytonal Jazz Mark McFarland AlthoughTaylorRJAZ_A_415412.sgm10.1080/17494060903152396Jazz1749-4060Original2009320000002009MarkMcFarlandkashchei@mac.com Perspectives and& Article Francis (print)/1749-4079Francis (online) Dave Brubeck is universally known as a jazz pianist, he describes himself as “a composer who plays the piano.”1 This distinction highlights the lesser-known aspects of Brubeck’s career, including his formal training at both the University of the Pacific and Mills College, as well as the numerous “serious” works he has composed. Because of Brubeck’s thorough training in both classical and jazz idioms, he has often been described as the first musician to fuse jazz and classical music successfully.2 The meeting of classical and jazz idioms is pervasive in Brubeck’s output. For instance, he famously introduced asymmetric meter into jazz with his 1959 album Time Out, which includes the highly popular tunes “Take Five” (in quintuple meter) and “Blue Rondo à la Turk” (written in 9/8, but with an irregular grouping of beat divisions: 2 + 2 + 2 + 3). Brubeck incorporated an even more radical aspect of twenti- eth-century music into jazz through his use of polytonality.3 Polytonality is a term that has yet to be defined to the satisfaction of all, and such agreement will likely never happen.4 This impasse is due to the inherent contradiction of the term itself and the ambiguity of the musical technique. In its most literal inter- pretation, polytonality -

Newsletter the American Society March, 1971/Vol

NEWSLETTER THE AMERICAN SOCIETY MARCH, 1971/VOL. 4, NO. 1 OF UNIVERSITY COMPOSERS 1971 NATIONAL CONFERENCE Accommodations: Private dormitory facilities, $5 .00 Arrangements are nearing completion for the Society's single, $4.00 each double, meal tickets about $1.00 per Vlth Annual National Conference in Houston on April meal. The Ramada Inn (a typical motel), bus service to the 16-18, 1971. Jeffrey Lerner (University of Houston) is in campus, 24-hour restaurant, $10.50 single, $7.50 double, charge of concert planning and general arrangements. Elaine $6.50 triple. Families can be accommodated. Meals at Barkin and Edward Chudacoff (University of Michigan) are campus cafeterias are about $1.00. planning panels and papers. While matters are progressing nicely, it is still possible to suggest to either of these your Non-Conference attractions: Tour of the NASA Com own participation. plex, April 16 morning; Houston Symphony Concert, April I 18 at 2:30; Concert by the Lyric Art String Quartet, April Concerts now scheduled for Friday, April 16, and 14 at 8:30 (free); Ice Follies, April 13-23; The Houston Saturday, April 17, tentatively include music by Leo Kraft, Alley Theatre, museums, galleries, swimming, tennis, golf, Francis J. Pyle, Jerome Margolis, Edward Mattila, Ruth boating, the Astrodome, and many fine restaurants in the Wylie, David Burge, Alberto Ginastera, Elaine Barkin, nearby area. Michael Horvit, Elliot Borishansky, Jean Ivey, Jon Apple ton, and Lawrence Moss. A special feature of the Vlth Conference is the opening address by National Chairman David Burge. Burge will Responses to the conference questionnaire sent to the present a review of the achivements of the Society since its membership in November have been gratifying, and the inception and seek to provide a perspective for a thorough willingness of the members to suggest themselves for reconsideration by all members of the future of the presentations insures a high level of discussion. -

CRI SD 300 Dodge/Arel/Boretz Charles Dodge Folia (11:45) Jeanne Benjamin, Michele Gallien, David Gilbert, Allen Blustine, George

CRI SD 300 Dodge/Arel/Boretz Charles Dodge Folia (11:45) Jeanne Benjamin, Michele Gallien, David Gilbert, Allen Blustine, George Haas, Donald Butterfield, Robert Miller, Raymond Des Roches, Richard Fitz; Jacques-Louis Monod, conductor Extensions for Trumpet and Tape (8:05) Ronald Anderson, trumpet; tape computed at the Columbia University Computer Center Bülent Arel Mimiana II: Frieze (11–13:00) Realized at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center Benjamin Boretz Group Variations (for Computer) (11:45) Realized at the Princeton University Computer Center Charles Dodge (b Ames, Iowa, 1942) studied composition at the University of Iowa, Aspen, Tanglewood, and Columbia University. He numbers among his teachers Philip Bezanson, Darius Milhaud, Arthur Berger, Gunther Schuller, Chou Wen-chung, Jack Beeson, and Otto Luening. He studied electronic music with Vladimir Ussachevsky and computer music with Godfrey Winham. Mr. Dodge won his first (of four) BMI Student Composer Awards and his first (of two) Bearns Prizes while still an undergraduate. In 1970, with his mastery of computer music already well along, he became assistant professor of music at Columbia University, and the same year his Changes and Earth’s Magnetic Field appeared on Nonesuch Records. In 1971, he began research in computer-synthesized speech and vocal sounds at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, and continued to work there from 1972–73 on a Guggenheim Fellowship. In February 1974 he was visiting research musician at the University of California (San Diego) Center for Music Experiment. Folia was commissioned by the Fromm Music Foundation and was premiered under Melvin Strauss at the Berkshire Music Center in 1965; it is dedicated to Paul Fromm. -

Improvising Compose Yourself

Improvising Compose Yourself Scott Gleason The post–World War II era in the USA saw the emergence of an intense new strain of composing music, begun by Milton Babbitt (1916–2011) and students collected around him, at Princeton University. This high–modernist project also produced writings about music aspiring to the verifiability or corrigibility of scientific discourse, embodying the then–latest develop- ments in science, philosophy, and linguistics. By the 1960’s Princeton was the American center of avant–garde music composition, or, by extend- ing to include electronic music and a certain geographical imagination, Princeton and Columbia Universities and uptown Manhattan—comparable to Darmstadt in the cultural imagination. Supporting the composition was the theory and a discourse purportedly rid of subjectivity, and projected through the journal Perspectives of New Music (1962–current). The notion of there being such a thing as “Princeton Theory,” as distinct from other forms of music theory, has been with us for many decades, for Kerman (1963: 152–4) defined and problematized a “Princeton School”; Blasius (1997, 2) reports Godfrey Winham’s (1934–1975) unfortunately undated response to “a prospective ‘Princeton issue’ of the Journal of Music Theory”; and Kerman’s (1985, 60–112) critique can be read largely as a response to the composer/ theorists working at Princeton—Kerman’s own alma mater. It is difficult to overestimate the importance of Princeton Theory’s writings for a vigorous engagement with the image of music (theory) as a science, with musical discourse purified of “incorrigible” personal criticism, hermeneutics. But around 1970, something happened. The sustaining premises of music theory as a scientific pursuit were challenged by some of Babbitt’s own stu- dents and writers for Perspectives of New Music: prominently, Elaine Barkin, Benjamin Boretz, J. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1967-1968, Tanglewood

0$^ Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 1967 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the i Fromm Music Foundation X)S Hear the sound of the 20th century on RCAVICTOR Red Seal STRAVINSKY BARTOK: Violin Concerto No. 2 Music of Irving Fine rca Victor AGON hvnachoovi STRAVINSKY: Violin Concerto Boston symphony £ SCHULLER Joseph Silverstein conducted by 7 STUDIES on THEMES of PAUL KLEE Boston Symphony Orchestra/Erich Leinsdorf Erich Leinsdorf BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ERICH LEINSDORI and the composer Symphony 1962 / Toccata concertante serious Song for string orchestra rcaVictor a (@)The most trusted name in sound ^*t*^ BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH LEINSDORF, Director Joseph Silverstein, Chairman of the Faculty Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Emeritus Louis Speyer, Assistant Director Claude Frank, Acting Chairman of the Tanglewood Institute Harry J. Kraut, Administrator James Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Viola C. Aliferis, Assistant Administrator <r*sw<rd Festival of Contemporary American Music presented in cooperation with The Fromm Music Foundation Paul Fromm, President Fellowship Program Contemporary Music Activities Gunther Schuller, Head Stanley Silverman, Assistant Elliot Carter, Ross Lee Finney, Donald Martino, George Perle, Roger Sessions, Seymour Shifrin, Guest Teachers Paul Zukofsky, Fromm Teaching Fellow The Berkshire Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music sponsored by the boston symphony orchestra Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS 7 LDS PERSPECTIVES NEWOF MUSIC PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music and the problems of the composer. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Listening to Babbitt: Perception and Analysis Of

LISTENING TO BABBITT: PERCEPTION AND ANALYSIS OF MILTON BABBITT’S DU FOR SOPRANO AND PIANO by ERIN L. SULLIVAN (Under the Direction of Adrian Childs and Susan Thomas) ABSTRACT This paper explores the ways in which scholars can approach and meaningfully discuss the music of Milton Babbitt. Critics argue that the standard discourse constructs a binary division between how Babbitt’s music works and how it sounds—that is, the system-based analytical approach engenders an attitude that the only elements of Babbitt’s music warranting serious consideration are theoretical conceptions, not aural perceptions. An examination of Babbitt’s writings will reveal the motivations for, and importance of, this system-based discourse in the analysis of “contextual” musical languages. However, this rhetoric has its limitations as well, thus the second part of this paper offers an alternative, listening-based approach to Babbitt’s music by exploring the vivid interplay of compositional structures, poetic text, and perceived meaning of musical gestures in Babbitt’s song cycle, Du (1951). This paper concludes by suggesting possible means of reconciling aural perceptions and compositional structures within a larger framework of serial poetics. INDEX WORDS: Milton Babbitt, Serialism, Music Theory, Music Analysis, Music Discourse, Du, Song Cycle, American Music LISTENING TO BABBITT: PERCEPTION AND ANALYSIS OF MILTON BABBITT’S DU FOR SOPRANO AND PIANO by ERIN L. SULLIVAN B.S., Mary Washington College, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 Erin L. Sullivan All Rights Reserved LISTENING TO BABBITT: PERCEPTION AND ANALYSIS OF MILTON BABBITT’S DU FOR SOPRANO AND PIANO by ERIN L.