California State University Northridge Twelve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brown Alumni Monthly 9 )

"Living at Laurelmead on Blackstone Boulevard " is Like Living Back on Campus... Only Better Introducing the new Brown campus connection, Laurelmead on Blackstone Boulevard. Located only minutes from Brown, Laurelmead is a distinguished residential community for independent adults. Owners enjoy an engaging lifestyle with the assurance of 24-hour security and home and grounds maintenance services. The Laurelmead campus includes beautiful common areas, resident gardens, and walking trails along the Seekonk River. Find out why so many Brown and Pembroke alumni, retired faculty, and fellow colleagues have chosen to make Laurelmead their new home. Dining at Laurelmead: From elegant dining to cafe or pub dining... this is the meal plan we dreamed of as students. The Fitness Center: Yoga, aquatics, weights, are considered an elective. The Odeon at Laurelmead: Where a variety of lectures and perforinances are attended. Come visit Laurelmead during your LAURELMEAD^^ Distinguished Adult Cooperative Living next visit to Providence, or call for 355 Blackstone Boulevard more information at (800) 286-9550. Providence, Rhode Island 02906 (401) 273-9550 • (800) 286-9550 NAN BOUCHARD TRACY '46 ^SiWli>i«ii«.t«Ml6; PRODUCED BY THE ALUMNI RELATIONS OFFICE Inscribe your name on College Hill. I he Brown Alumni Association invites JL. you to celebrate your lifelong connection to Brown by purchasing a brick in the Alumni Walkway. Add your name - or the name of any alumnus or alumna you wish to honor or remem- ber - to the beautifully designed centerpiece of BROIfiN the upcoming Maddock /\ | ^ [^ l\V±y 1 Alumni Center garden ASSOCIATION restoration project. Celehratintj Our THE PROPOSED ALUMNI WALKWAY Connections to Brown MADDOCK ALUMNI CENTER, BROWN UNIVERSITY Join the hundreds of alumni who have already purchased their bricks! ORDERED BY NAME . -

Afsnet.Org 2014 American Folklore Society Officers

American Folklore Society Keeping Folklorists Connected Folklore at the Crossroads 2014 Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts 2014 Annual Meeting Committee Executive Board Brent Björkman (Kentucky Folklife Program, Western The annual meeting would be impossible without these Kentucky University) volunteers: they put together sessions, arrange lectures, Maria Carmen Gambliel (Idaho Commission on the special events, and tours, and carefully weigh all proposals Arts, retired) to build a strong program. Maggie Holtzberg (Massachusetts Cultural Council) Margaret Kruesi (American Folklife Center) Local Planning Committee Coordinator David Todd Lawrence (University of St. Thomas) Laura Marcus Green (independent) Solimar Otero (Louisiana State University) Pravina Shukla (Indiana University) Local Planning Committee Diane Tye (Memorial University of Newfoundland) Marsha Bol (Museum of International Folk Art) Carolyn E. Ware (Louisiana State University) Antonio Chavarria (Museum of Indian Arts and Culture) Juwen Zhang (Willamette University) Nicolasa Chavez (Museum of International Folk Art) Felicia Katz-Harris (Museum of International Folk Art) Melanie LaBorwit (New Mexico Department of American Folklore Society Staff Cultural Affairs) Kathleen Manley (University of Northern Colorado, emerita) Executive Director Claude Stephenson (New Mexico State Folklorist, emeritus) Timothy Lloyd Suzanne Seriff (Museum of International Folk Art) [email protected] Steve Green (Western Folklife Center) 614/292-3375 Review Committee Coordinators Associate Director David A. Allred (Snow College) Lorraine Walsh Cashman Aunya P. R. Byrd (Lone Star College System) [email protected] Nancy C. McEntire (Indiana State University) 614/292-2199 Elaine Thatcher (Heritage Arts Services) Administrative and Editorial Associate Review Committee Readers Rob Vanscoyoc Carolyn Sue Allemand (University of Mary Hardin-Baylor) [email protected] Nelda R. -

A Catholic Minority Church in a World of Seekers, Final

Tilburg University A Catholic minority church in a world of seekers Hellemans, Staf; Jonkers, Peter Publication date: 2015 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hellemans, S., & Jonkers, P. (2015). A Catholic minority church in a world of seekers. (Christian Philosophical Studies; Vol. XI). Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. sep. 2021 Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series IV. Western Philosophical Studies, Volume 9 Series VIII. Christian Philosophical Studies, Volume 11 General Editor George F. McLean A Catholic Minority Church in a World of Seekers Western Philosophical Studies, IX Christian Philosophical Studies, XI Edited by Staf Hellemans Peter Jonkers The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2015 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. -

HCS — History of Classical Scholarship

ISSN: 2632-4091 History of Classical Scholarship www.hcsjournal.org ISSUE 1 (2019) Dedication page for the Historiae by Herodotus, printed at Venice, 1494 The publication of this journal has been co-funded by the Department of Humanities of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology of Newcastle University Editors Lorenzo CALVELLI Federico SANTANGELO (Venezia) (Newcastle) Editorial Board Luciano CANFORA Marc MAYER (Bari) (Barcelona) Jo-Marie CLAASSEN Laura MECELLA (Stellenbosch) (Milano) Massimiliano DI FAZIO Leandro POLVERINI (Pavia) (Roma) Patricia FORTINI BROWN Stefan REBENICH (Princeton) (Bern) Helena GIMENO PASCUAL Ronald RIDLEY (Alcalá de Henares) (Melbourne) Anthony GRAFTON Michael SQUIRE (Princeton) (London) Judith P. HALLETT William STENHOUSE (College Park, Maryland) (New York) Katherine HARLOE Christopher STRAY (Reading) (Swansea) Jill KRAYE Daniela SUMMA (London) (Berlin) Arnaldo MARCONE Ginette VAGENHEIM (Roma) (Rouen) Copy-editing & Design Thilo RISING (Newcastle) History of Classical Scholarship Issue () TABLE OF CONTENTS LORENZO CALVELLI, FEDERICO SANTANGELO A New Journal: Contents, Methods, Perspectives i–iv GERARD GONZÁLEZ GERMAIN Conrad Peutinger, Reader of Inscriptions: A Note on the Rediscovery of His Copy of the Epigrammata Antiquae Urbis (Rome, ) – GINETTE VAGENHEIM L’épitaphe comme exemplum virtutis dans les macrobies des Antichi eroi et huomini illustri de Pirro Ligorio ( c.–) – MASSIMILIANO DI FAZIO Gli Etruschi nella cultura popolare italiana del XIX secolo. Le indagini di Charles G. Leland – JUDITH P. HALLETT The Legacy of the Drunken Duchess: Grace Harriet Macurdy, Barbara McManus and Classics at Vassar College, – – LUCIANO CANFORA La lettera di Catilina: Norden, Marchesi, Syme – CHRISTOPHER STRAY The Glory and the Grandeur: John Clarke Stobart and the Defence of High Culture in a Democratic Age – ILSE HILBOLD Jules Marouzeau and L’Année philologique: The Genesis of a Reform in Classical Bibliography – BEN CARTLIDGE E.R. -

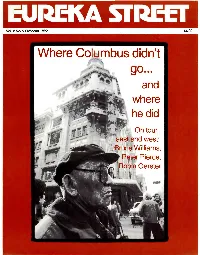

And Where He Did

Vol. 2 No. 9 October 1992 $4.00 and where he did Volume 2 Number 9 I:URI:-KA STRI:-eT October 1992 A m agazine of public affairs, the arts and theology 21 CoNTENTS TOPGUN Michael McGirr reports on gun laws and the calls for capital punishment in the 4 Philippines. COMMENT In this year of elections we are only as good 22 as our choices, says Peter Steele. Andrew DON'T KISS ME, HARDY Hamilton looks at the Columbus quin James Griffin concludes his series on the centary, and decides that the past must be Wren-Evatt letters. owned as well as owned up to (pS). 6 25 ORIENTATIONS LETTERS Peter Pierce and Robin Gerster take their pens to Shanghai and Saigon; Emmanuel 7 Santos and Hwa Goh take their cameras to COMMISSIONS AND OMISSIONS Tianjin. ICAC chief Ian Temby Margaret Simons talks to Australia's top speaks for himself: p 7 crime-busters. 34 11 BOOKS AND ARTS Cover photo: A member of Was the oldest part of the Pentateuch CAPITAL LETTER the Tianjing city planning office written by a woman? Kevin Hart reviews in Jei Fang Bei Road, three books by Harold Bloom, who thinks the 'Wall Street' of Tianjin. 12 it was; Robert Murray sizes up Columbus BLINDED BY THE LIGHT and colonialism (p38 ). Cover photo and photos pp25, 29 and 30 Bruce Williams visits the Columbus light by Emmanuel Santos; house in Santo Domingo, and wonders who Photo p27 by Hwa Goh; will be enlightened. 40 Photos p12 by Belinda Bain; FLASH IN THE PAN Photo p41 by Bill Thomas; 15 Reviews of the films Patriot Games Cartoons pp6, 36 and 3 7 by Dean Moore; Zentropa, Edward II, and Deadly. -

The Process and Adaptation of the Ministries of the Wausau Seventh-Day Adventist Church in the Postmodern Matrix to Those Born After 1964

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2005 The Process and Adaptation of the Ministries of the Wausau Seventh-day Adventist Church in the Postmodern Matrix to Those Born After 1964 William Shelby Bossert Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Recommended Citation Bossert, William Shelby, "The Process and Adaptation of the Ministries of the Wausau Seventh-day Adventist Church in the Postmodern Matrix to Those Born After 1964" (2005). Dissertation Projects DMin. 20. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/20 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title; THE PROCESS AND ADAPTATION OF THE MINISTRIES OF THE WAUSAU SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN THE POSTMODERN MATRIX TO THOSE BORN AFTER 1964 Name of researcher: William S. Bossert Name of faculty adviser: Barry Gane, D.Min. Date completed: December 2005 Problem It was apparent to many of the Wausau Seventh-day Adventist Church members, as well as the pastor, that there was an apparent lack or minimal level of participation of young adults (ages 17-35) in the life of the church. -

The Methodology of Resistance in Contemporary Neopaganism

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2012 The ethoM dology of Resistance in Contemporary NeoPaganism Rebecca Short [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Short, Rebecca, "The eM thodology of Resistance in Contemporary NeoPaganism" (2012). Summer Research. Paper 151. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rebecca Short 24 September 2012 Professor Greta Austin The Methodology of Resistance in Contemporary NeoPagan Culture The number of adherents of NeoPaganism is one of the fastest growing, doubling in numbers about every eighteen months. 1 NeoPaganism is a set of several religious traditions and spiritualities that seek to either (1) painstakingly reconstruct the indigenous religions of the Christianized world, especially those of Europe, or (2) reinterpret these religions in the contemporary era to formulate new religious traditions. Reconstructionist NeoPagan traditions include Asatru , a Norse Reconstructionist path, and Hellenismos , a Greek Reconstructionist religion. More contemporary, eclectic, new religious movements include Wicca, a tradition of religious witchcraft born out of the ancient Hermetic school of spirituality and magic practice. Wicca is by far the most popular tradition (or, now, set of traditions) in all of NeoPaganism. This religious tradition was started by a man named Gerald Gardner in 1950s England. -

Ferguson New Religions and Esotericism.Pdf

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a chapter published by Taylor & Francis Group in Denisoff D & Schaffer T (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Victorian Literature. Routledge Literature Companions. Abingdon: Routledge on 4 Nov 2019, available online: https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Companion-to-Victorian-Literature-1st- Edition/Denisoff-Schaffer/p/book/9781138579866 New Religions and Esotericism For many years, the story of religion in nineteenth-century Britain was narrated primarily, even sometimes exclusively, in relation to doubt, decline, and disenchantment. Drawing upon an evocative literary terrain composed of Matthew Arnold’s receding Sea of Faith and John Ruskin’s dreadful Hammers (Arnold 21; Ruskin 115)., scholars painted the period as one in which secularization was inevitable, undeterred, and productive of crisis. Indeed, writing in 1977, Robert Lee Wolff suggests that religious doubt was so inescapable during the years of Victoria’s reign that practically every citizen experienced their own bespoke variety of it. “Victorians,” he writes, “were troubled not only about what to believe and how to practice their religion, but also about whether to believe at all, and how continued belief might be possible [. .] There seem at time to have been as many varieties of doubt as there were human beings in Victorian England” (2). While staking this claim in an introduction to a reprint series of one hundred and twenty-one Victorian novels specifically selected to reflect the faith and doubt paradigm, Wolff makes no allowance for a possible incongruence between his pointed thematic focus and the experience of the general populace at large. Surveying a demographic which grew in size from some thirteen to thirty-two million between 1837 and 1901, he confidently assigns to it a single spiritual keynote: doubt. -

The New Buddhism: the Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition

The New Buddhism: The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS the new buddhism This page intentionally left blank the new buddhism The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman 1 1 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and an associated company in Berlin Copyright © 2001 by James William Coleman First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, 10016 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2002 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coleman, James William 1947– The new Buddhism : the western transformation of an ancient tradition / James William Coleman. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-19-513162-2 (Cloth) ISBN 0-19-515241-7 (Pbk.) 1. Buddhism—United States—History—20th century. 2. Religious life—Buddhism. 3. Monastic and religious life (Buddhism)—United States. I.Title. BQ734.C65 2000 294.3'0973—dc21 00-024981 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America Contents one What -

Contemporary Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Europe

CONTEMPORARY PAGAN AND NATIVE FAITH MOVEMENTS IN EUROPE EASA Series Published in Association with the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) Series Editor: Eeva Berglund, Helsinki University Social anthropology in Europe is growing, and the variety of work being done is expanding. This series is intended to present the best of the work produced by members of the EASA, both in monographs and in edited collections. The studies in this series describe societies, processes, and institutions around the world and are intended for both scholarly and student readerships. 1. LEARNING FIELDS 14. POLICY WORLDS Volume 1 Anthropology and Analysis of Contemporary Educational Histories of European Social Power Anthropology Edited by Cris Shore, Susan Wright and Davide Edited by Dorle Dracklé, Iain R. Edgar and Però Thomas K. Schippers 15. HEADLINES OF NATION, SUBTEXTS 2. LEARNING FIELDS OF CLASS Volume 2 Working Class Populism and the Return of the Current Policies and Practices in European Repressed in Neoliberal Europe Social Anthropology Education Edited by Don Kalb and Gabor Halmai Edited by Dorle Dracklé and Iain R. Edgar 16. ENCOUNTERS OF BODY AND SOUL 3. GRAMMARS OF IDENTITY/ALTERITY IN CONTEMPORARY RELIGIOUS A Structural Approach PRACTICES Edited by Gerd Baumann and Andre Gingrich Anthropological Reflections Edited by Anna Fedele and Ruy Llera Blanes 4. MULTIPLE MEDICAL REALITIES Patients and Healers in Biomedical, Alternative 17. CARING FOR THE ‘HOLY LAND’ and Traditional Medicine Filipina Domestic Workers in Israel Edited by Helle Johannessen and Imre Lázár Claudia Liebelt 5. FRACTURING RESEMBLANCES 18. ORDINARY LIVES AND GRAND Identity and Mimetic Conflict in Melanesia and SCHEMES the West An Anthropology of Everyday Religion Simon Harrison Edited by Samuli Schielke and Liza Debevec 6. -

Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic

Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic Series Editors Jonathan Barry Department of History University of Exeter Exeter, UK Willem de Blécourt Meertens Institute Amsterdam The Netherlands Owen Davies School of Humanities University of Hertfordshire UK The history of European witchcraft and magic continues to fascinate and challenge students and scholars. There is certainly no shortage of books on the subject. Several general surveys of the witch trials and numerous regional and micro studies have been published for an English-speaking readership. While the quality of publications on witchcraft has been high, some regions and topics have received less attention over the years. The aim of this series is to help illuminate these lesser known or little studied aspects of the history of witchcraft and magic. It will also encourage the development of a broader corpus of work in other related areas of magic and the supernatural, such as angels, devils, spirits, ghosts, folk healing and divination. To help further our understanding and interest in this wider history of beliefs and practices, the series will include research that looks beyond the usual focus on Western Europe and that also explores their relevance and infuence from the medieval to the modern period. ‘A valuable series.’—Magic, Ritual and Witchcraft More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14693 Michael Ostling Editor Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits ‘Small Gods’ at the Margins of Christendom Editor Michael Ostling Arizona State University Tempe, USA Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic ISBN 978-1-137-58519-6 ISBN 978-1-137-58520-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58520-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017944566 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

APPROACHING ESOTERICISM and MYSTICISM Cultural Inluences

APPROACHING ESOTERICISM AND MYSTICISM Cultural Inluences APPROACHING ESOTERICISM AND MYSTICISM Cultural Influences Based on papers presented at the conference arranged by the Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History and the research project ‘Seekers of the New: Esotericism and the Transformation of Religiosity in the Modernising Finland’, Turku/Åbo, Finland, on 5–7 June 2019 Edited by MAARIT LESKELÄ-KÄRKI and TIINA MAHLAMÄKI Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 29 Turku/Åbo 2020 Editorial secretary Maria Vasenkari Linguistic editing Vidyasakhi Sarah Bannock ISSN 0582-3226 ISBN 978-952-12-3974-8 (print), 978-952-12-3975-5 (online) Abografi Åbo 2020 Table of contents Maarit Leskelä-Kärki and Tiina Mahlamäki New currents in the research on esotericism and mysticism 1 Olav Hammer Mysticism and esotericism as contested taxonomical categories 5 Maarit Leskelä-Kärki Ethical encounters in the archives: on studying individuals in esoteric contexts 28 Pekka Pitkälä Sigurd Wettenhovi-Aspa, August Strindberg and a dispute concerning the common origins of the languages of mankind 1911–12 49 Hippo Taatila A history of violence: the concrete and metaphorical wars in the life narrative of G. I. Gurdjief 82 Tiina Mahlamäki and Tomas Mansikka Interpretations of Emanuel Swedenborg’s image of the afterlife in the novel Oneiron by Laura Lindstedt 103 Billy Gray Rumi, Suf spirituality and the teacher–disciple relationship in Eli Shafak’s Te Forty Rules of Love 124 Carles Magrinyà Badiella Experiencing the limits: the cave as a transitional