An Exploration of Repetition and Authenticity in Bob Dylan’S Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russell Gulley Alabama Touring Artist Program

Alabama Touring Artist Program Study Guide Russell Gulley Intro: FROM TRADITIONAL MUSIC TO AMERICAN POP 265-845-0203 [email protected] Artistic Genre: Music Performing Artist: Russell Gulley 1 Alabama Touring Artist Program Study Guide presented by Alabama State Council on the Arts 201 Monroe Street, Suite 110; Montgomery, AL 36130-1800 334-242-4076 Ext. 241 Alabama Touring Artist Program presented by the Alabama State Council on the Arts This Study Guide has been prepared for you by the Alabama State Council on the Arts in collaboration with the performing artist. All vocabulary that is arts related is taken directly from the Alabama Course of Study, Arts Education. With an understanding that each teacher is limited to the amount of time that may be delegated to new ideas and subjects, this guide is both brief and designed in a way that we hope supports your school curriculum. We welcome feedback and questions, and will offer additional consulting on possible curriculum connections and unit designs should you desire this support. Please feel free to request further assistance and offer your questions and feedback. Hearing from educators helps to improve our programs for other schools and educators in the future. Please Contact: Diana F. Green, Arts in Education Program Manager at: 334/242-4076 Ext. 241 [email protected] Set up: Artists typically arrive 60 minutes before their scheduled performance in order to set up. Please have the space available to the artist as soon as she arrives. All artists will need some kind of setup prior to arrival. -

Bob Dylan: the 30 Th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances in March

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS “Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in March A veritable Who’s Who of the music scene includes Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Petty, Tracy Chapman, George Harrison and others Great Performances presents a special encore of highlights from 1992’s star-studded concert tribute to the American pop music icon at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration in March on PBS (check local listings). (In New York, THIRTEEN will air the concert on Friday, March 7 at 9 p.m.) Selling out 18,200 seats in a frantic, record-breaking 70 minutes, the concert gathered an amazing Who’s Who of performers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the enigmatic singer- songwriter’s groundbreaking debut album from 1962, Bob Dylan . Taking viewers from front row center to back stage, the special captures all the excitement of this historic, once-in-a-lifetime concert as many of the greatest names in popular music—including The Band , Mary Chapin Carpenter , Roseanne Cash , Eric Clapton , Shawn Colvin , George Harrison , Richie Havens , Roger McGuinn , John Mellencamp , Tom Petty , Stevie Wonder , Eddie Vedder , Ron Wood , Neil Young , and more—pay homage to Dylan and the songs that made him a legend. -

Still on the Road 1980 Saved Sessions

STILL ON THE ROAD 1980 SAVED SESSIONS FEBRUARY 11 Sheffield, Alabama Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, 1st Saved recording session 12 Sheffield, Alabama Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, 2nd Saved recording session 13 Sheffield, Alabama Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, 3rd Saved recording session 14 Sheffield, Alabama Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, 4th Saved recording session 15 Sheffield, Alabama Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, 5th Saved recording session 27 Los Angeles, California Shrine Auditorium, 22nd Annual Grammy Award Ceremony MARCH Los Angeles, California United Western Studios, Keith Green recording session Still On The Road: 1980 Saved Sessions 5551 Muscle Shoals Sound Studio Sheffield, Alabama 11 February 1980 1st Saved recording session produced by Jerry Wexler & Barry Beckett. 1. Covenant Woman 2. Covenant Woman 3. Covenant Woman 4. Covenant Woman 5. Covenant Woman 6. Covenant Woman 7. Covenant Woman 8. Covenant Woman 9. Covenant Woman 10. Covenant Woman 11. Covenant Woman Bob Dylan (vocal & guitar), Fred Tackett (guitar), Spooner Oldham (keyboards), Terry Young (acoustic piano), Barry Beckett (electric piano), Tim Drummond (bass), Jim Keltner (drums). Official release 3 released on Bob Dylan: Trouble No More. The Bootleg Series Vol. 13 1979-1981, Disc Three: Rare and Unreleased, Columbia 88985454652-2, 3 November 2017 References Michael Krogsgaard: Bob Dylan: The Recording Sessions (Part 4). The Telegraph #56, Winter 1997, pp. 168- 176. Clinton Heylin: Bob Dylan. The Recording Sessions [1960 – 1994]. St. Martin’s Press December 1995, pp 131– 136. Clinton Heylin: Trouble In Mind. Bob Dylan’s Gospel Years. What really happened. Chapter 6. Where I Will Always Be Renewed, (January – February 1980). Lesser Gods 2017. -

Jerry Williams Jr. Discography

SWAMP DOGG - JERRY WILLIAMS, JR. DISCOGRAPHY Updated 2016.January.5 Compiled, researched and annotated by David E. Chance: [email protected] Special thanks to: Swamp Dogg, Ray Ellis, Tom DeJong, Steve Bardsley, Pete Morgan, Stuart Heap, Harry Grundy, Clive Richardson, Andy Schwartz, my loving wife Asma and my little boy Jonah. News, Info, Interviews & Articles Audio & Video Discography Singles & EPs Albums (CDs & LPs) Various Artists Compilations Production & Arrangement Covers & Samples Miscellaneous Movies & Television Song Credits Lyrics ================================= NEWS, INFO, INTERVIEWS & ARTICLES: ================================= The Swamp Dogg Times: http://www.swampdogg.net/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/SwampDogg Twitter: https://twitter.com/TheSwampDogg Swamp Dogg's Record Store: http://swampdogg.bandcamp.com/ http://store.fastcommerce.com/render.cz?method=index&store=sdeg&refresh=true LIVING BLUES INTERVIEW The April 2014 issue of Living Blues (issue #230, vol. 45 #2) has a lengthy interview and front cover article on Swamp Dogg by Gene Tomko. "There's a Lot of Freedom in My Albums", front cover + pages 10-19. The article includes a few never-before-seen vintage photos, including Jerry at age 2 and a picture of him talking with Bobby "Blue" Bland. The issue can be purchased from the Living Blues website, which also includes a nod to this online discography you're now viewing: http://www.livingblues.com/ SWAMP DOGG WRITES A BOOK PROLOGUE Swamp Dogg has written the prologue to a new book, Espiritus en la Oscuridad: Viaje a la era soul, written by Andreu Cunill Clares and soon to be published in Spain by 66 rpm Edicions: http://66-rpm.com/ The jacket's front cover is a photo of Swamp Dogg in the studio with Tommy Hunt circa 1968. -

Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize

BOB ENNOBLED BOB DYLAN AND THE NOBEL PRIZE I am a Dylan fan and I know many of his songs by heart. I have seen him perform and have heard him mangle his own work in Birmingham, England, and then delight the Hammersmith Odeon. I have watched him forget some of the words to ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ in the Leisure Centre at Bournemouth. Indeed, since about 1963 and The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan I have spent many leisure hours and vital pounds, first of pocket money and then of earned income, keeping up with much of Dylan’s copious output. I’ve even tried to read his ‘novel’ Tarantula. While I am aware of his vocal and musical limitations and the way he can move from brilliant to dire, I love some of his songs, his phrasing and intonation this side of idolatry and sometimes beyond. I think the first four Dylan tracks I bought were on an 1963 EP called Dylan (Extended Play: remember those?) which rotated on the turntable at 45 rpm as his astonishing twenty-one-year old-voice sang: ‘Don’t Think Twice, it’s alright’, ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, ‘When the Ship Comes in’ and then was it ‘Corinna, Corinna’? His way with song words has long held my qualified admiration and I enjoyed reading his Chronicles (Volume One) when they came out in 2004. For me, even with Dylan at his uneven best, it’s the words that matter most and the way he delivers them in the best of his supremely memorable songs. If I had to name my current top ten of his tracks, chosen with particular attention to the words and to do so rapidly from memory, I’d probably go for the following: ‘Boots -

Shoosh 800-900 Series Master Tracklist 800-977

SHOOSH CDs -- 800 and 900 Series www.opalnations.com CD # Track Title Artist Label / # Date 801 1 I need someone to stand by me Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 2 A thousand miles away Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 3 You don't own your love Nat Wright & Singers ABC-Paramount 10045 1959 801 4 Please come back Gary Warren & Group ABC-Paramount 9861 1957 801 5 Into each life some rain must fall Zilla & Jay ABC-Paramount 10558 1964 801 6 (I'm gonna) cry some time Hoagy Lands & Singers ABC-Paramount 10171 1961 801 7 Jealous love Bobby Lewis & Group ABC-Paramount 10592 1964 801 8 Nice guy Martha Jean Love & Group ABC-Paramount 10689 1965 801 9 Little by little Micki Marlo & Group ABC-Paramount 9762 1956 801 10 Why don't you fall in love Cozy Morley & Group ABC-Paramount 9811 1957 801 11 Forgive me, my love Sabby Lewis & the Vibra-Tones ABC-Paramount 9697 1956 801 12 Never love again Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 13 Confession of love Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10341 1962 801 14 My heart V-Eights ABC-Paramount 10629 1965 801 15 Uptown - Downtown Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 16 Bring back your heart Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10208 1961 801 17 Don't restrain me Joe Corvets ABC-Paramount 9891 1958 801 18 Traveler of love Ronnie Haig & Group ABC-Paramount 9912 1958 801 19 High school romance Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 20 I walk on Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 21 I found a girl Scott Stevens & The Cavaliers ABC-Paramount -

Abandoned Love: the Impact of Wyatt V. Stickney on the Intersection

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2011 Abandoned Love: The mpI act of Wyatt .v Stickney on the Intersection between International Human Rights and Domestic Mental Disability Law Michael L. Perlin New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Disability Law Commons, and the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Law & Psychology Review, Vol. 35, pp. 121-142 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. "ABANDONED LOVE": THE IMPACT OF WYATT V. STICKNEY ON THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND DOMESTIC MENTAL DISABILITY LAW Michael L. Perlin* INTRODUCTION Wyatt v. Stickney' is the most important institutional rights case liti- gated in the history of domestic mental disability law.2 It spawned copycat litigation in multiple federal district courts and state superior courts ;3 it led directly to the creation of Patients' Bills of Rights in most states;4 and it inspired the creation of the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act,' the Mental Health Systems Act Bill of Rights,6 and the federally-funded Protection and Advocacy System.7 Its direct influence on the development of the right-to-treatment doctrine abated after the Su- preme Court's disinclination, in its 1982 decision in Youngberg v. Romeo,8 to find that right to be constitutionally mandated, but its historic role as a beacon and inspiration has never truly faded. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia KOUVAROU, MARIA How to cite: KOUVAROU, MARIA (2011) `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1391/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Maria Kouvarou MA by Research in Musicology Music Department Durham University 2011 Maria Kouvarou ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Abstract Bob Dylan’s work has frequently been the object of discussion, debate and scholarly research. It has been commented on in terms of interpretation of the lyrics of his songs, of their musical treatment, and of the distinctiveness of Dylan’s performance style, while Dylan himself has been treated both as an important figure in the world of popular music, and also as an artist, as a significant poet. -

Tell Tale Signs

I don't know anybody who's made a record that sounds decent in the past 20 years, really. You listen to these modern records, they're atrocious, they have sound all over them. There's no definition of nothing, no vocal, no nothing,… remember when that Napster guy came up across, it was like, ‘Everybody’s gettin’ music for free.’ I was like, ‘Well, why not? It ain’t worth nothing anyway. Bob Dylan 2006 A compilation of bits and Bobs from last 30 years? That'll be $129.99. Sony 2008 --- Introduction: I wrote this very soon after the release of Tell Tale Signs. Although I was presuming ISIS would be delayed in order to allow a more considered take on the release, my own work commitments demanded an early response in any case. I have presented it as a dialogue that highlights – if not exaggerates – trends I have felt in myself and in discussions amongst Dylan fans at large. I have taken the liberty of framing the dialogue in a setting plagiarised brazenly from a classic as Bob does with many an out of copyright source as Dylan Cynic would say or, if you are aligned to Dylan Enthusiast rather than Dylan Cynic, the framework of the dialogue alludes intriguingly to a past literary master in much the same way Dylan binds his own work artistically to Ovid in Modern Times. I won’t mention the play it comes from as the fun is surely always in the searching and then deciding if it is just rip-off or a deeply thought allusion that adds to the whole. -

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony Tahanie Aboushi | New York, New York I am counsel for Dounya Zayer, the protestor who was violently shoved by officer D’Andraia and observed by Commander Edelman. I would like to appear with Dounya to testify at this hearing and I will submit written testimony at a later time but well before the June 15th deadline. Thank you. Marissa Abrahams | South Beach Psychiatric Center | Brooklyn, New York As a nurse, it has been disturbing to see first-hand how few NYPD officers (present en masse at ALL peaceful protests) are wearing the face masks that we know are preventing the spread of COVID-19. Demonstrators are taking this extremely seriously and I saw NYPD literally laugh in the face of a protester who asked why they do not. It is negligent and a blatant provocation -especially in the context of the over-policing of Black and Latinx communities for social distancing violations. The complete disregard of the NYPD for the safety of the people they purportedly protect and serve, the active attacks with tear gas and pepper spray in the midst of a respiratory pandemic, is appalling and unacceptable. Aaron Abrams | Brooklyn, New York I will try to keep these testimonies as precise as possible since I know your office likely has hundreds, if not thousands to go through. Three separate occasions highlighted below: First Incident - May 30th - Brooklyn - peaceful protestors were walking from Prospect Park through the streets early in the day. At one point, police stopped to block the street and asked that we back up. -

The Lowdown Songlist

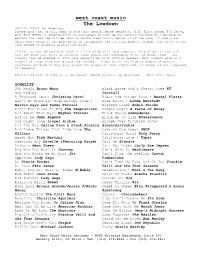

west coast music The Lowdown SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need to have your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, F/D Dance, etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm the band will be able to perform the song and will be able to locate sheet music, mp3 or CD of the song. If some cases where sheet music is not printed or an arrangement for the full band is needed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. If you desire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we would ask for a minimum 80 requests. Please feel free to call us at the office should you have any questions. – West Coast Music SONGLIST: 24K Magic Bruno Mars Black Horse And A Cherry Tree KT 90s Medley Tunstall A Thousand Years Christina Perri Bless the Broken Road – Rascal Flatts Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Duet) Blue Bayou – Linda Ronstadt Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations Boogie Oogie A Taste Of Honey All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Brick House Commodores All Of Me John Legend Bring Me To Life Evanescence All Night Long Lionel Richie Bridge Over Troubled -

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album.