I Popular but Disparaged: Sonata Structures in Tchaikovsky's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridge the Annual Meeting of the Gen- American Miss Mabel Legion by Frank B

Legion Auxiliary OES Activities Aids Veterans’ Folk; fort In Local Dupont Post Music Other Activities Chapters Bridge The annual meeting of the Gen- American Miss Mabel Legion By Frank B. Lord. F. Staub, president eral Auxiliary Home Board will be of the District of Columbia Depart- held at One pair playing in the Northern 1:30 p.m. tomorrow for Officers Installed ment, the American Legion Aux- election Virginia championship bridge tour- of officers. iliary, announced last week that 58 Lee R. Pennington, commander of By James Waldo Fawcett. nament held last week at the Ward- Meetings announced are: needy children of World War II the District of Columbia Depart- Notes man a Readers of The Star, whether Park Hotel established near- veterans have been Electa Chapter—Tuesday, initia- ment, the American Legion, and his assisted finan- collectors are record for the magnitude of the set tion of 10 and stamp or not. invited cially since September 1, at a candidates; ways staff, last week installed officers of Orchestra which administered to their 1944, to attend a meeting of the Wash- Plays they cost of $2,691.60. means card party Saturday eve- the new Fort Dupont Post, at the adversaries in the qualifying round 3925 ington Philatelic Society at the Na- The American Legion Auxiliary ning, Alabama avenue S.E. St. Francis Xavier School. Three Concerts of the open pair match. William tional Museum Auditorium, Consti- Child Welfare Committee, under Naomi Chapter—Tuesday, re- They are as follows: R. H. Ran- Cheeks and on tution avenue at Ninth street N.W, Mrs. -

2019-2020 Symphonic Series

Robert Spano, Principal Guest Conductor Keith Cerny, Ph.D., President & CEO 2019-2020 SYMPHONIC SERIES Friday – Sunday, Ocotber 11-13, 2019 Miguel Harth-Bedoya, Conductor Nancy Lee & Perry R. Bass Chair Kelley O'Connor, Mezzo-Soprano Fort Worth Kantorei, Maritza Cáceres, Director Texas Boys Choir, Kerra Simmons, Interim Artistic Director MAHLER Symphony No. 3 in D Minor Part 1 Introduction. With force and decision Part 2 Tempo di menutto. Very Moderately Comodo. Scherzando. Unhurriedly Very Slow. Misterioso - Joyous in tempo and jaunty in expression Slow. Calm. Deeply felt This concert will be performed without intermission Special thanks to Rosalyn G. Rosenthal Video or audio recording of this performance is strictly prohibited. Patrons arriving late will be seated during the first convenient pause. Program and artists are subject to change. FORT WORTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA | 7 PROGRAM NOTES BY KEN MELTZER Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Symphony No. 3 in D minor (1896) 99 minutes Alto solo, women’s chorus, boys’ chorus, 4 piccolos, 4 flutes, 4 oboes, English horn, 2 E-flat clarinets, 4 clarinets, bass clarinet, 4 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, 4 trumpets, posthorn (offstage), 4 trombones, tuba, timpani (two players), bass drum, chimes, cymbals, glockenspiel, rute, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, 2 harps, and strings. Mahler’s Third In the summer of 1894, Gustav Mahler completed his Symphony is epic Symphony No. 2. Known as the “Resurrection,” the both in its length Mahler Second is a massive work in five movements, and complement featuring two vocal soloists, a large chorus, and orchestra. of performing A performance of the “Resurrection” Symphony lasts forces. -

Middle Power Music: Modernism, Ideology, and Compromise in English Canadian Cold War Composition

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Middle Power Music: Modernism, Ideology, and Compromise in English Canadian Cold War Composition A Dissertation Presented by Sarah Christine Emily Hope Feltham to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music History and Theory Stony Brook University December 2015 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Sarah Christine Emily Hope Feltham We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Dr. Ryan Minor - Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of Music, Stony Brook University Dr. Sarah Fuller - Chairperson of Defense Professor Emerita, Department of Music, Stony Brook University Dr. Margarethe Adams Assistant Professor, Department of Music, Stony Brook University Dr. Robin Elliott—Outside Reader Professor (Musicology), Jean A. Chalmers Chair in Canadian Music Faculty of Music, University of Toronto This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Middle Power Music: Modernism, Ideology, and Compromise in English Canadian Cold War Composition by Sarah Feltham Doctor of Philosophy in Music History and Theory Stony Brook University December 2015 This dissertation argues that English Canadian composers of the Cold War period produced works that function as “middle power music.” The concept of middlepowerhood, central to Canadian policy and foreign relations in this period, has been characterized by John W. -

RSO History.Indd

A HISTORY OF THE 1940-2020 Compiled by present and past members and trustees of the Ridgewood Symphony Orchestra. Copyright © 2019 by the Ridgewood Symphony Orchestra TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 From 1940 to 2020: Overview 1 Pg. 3 03 In the Beginning 04 The Forties 05 The Bergethon Years 06 The Christmann Years 07 The Lochner Years Pg. 5 08 The Eighties 09 The Dackow Years 11 Carnegie and Avery Fisher Halls 12 The Big “60” Celebration 13 The Gary Fagin Years Pg. 11 14 The Diane Wittry Years 15 The Arkady Leytush Years 16 Segue: The RSO Looks Ahead 17 RSO Festival Strings 17 Educational Outreach Pg. 17 FROM 1940 TO 2020: OVERVIEW tors who had friendly connections throughout the pro- fessional music world, resulting in the many guest ap- pearances by excellent world-class soloists. Ridgewood The Ridgewood Symphony Orchestra celebrates its and environs also proved to have a sterling collection of 80th anniversary in the 2019-2020 season. Now a mod- professional and student musicians. ern orchestra with about 100 musicians, the RSO has A clear highlight in the orchestra’s history was its grown light years from the 28 musicians who played in appearance in two of the legendary musical venues in the inaugural concert in the spring of 1940 with the New York City. The orchestra was invited to play at Av- likewise fl edgling Ridgewood Gilbert and Sullivan ery Fisher Hall in 1992, and at Carnegie Hall in both Company. 1992 and 1998. It has been joyous musical journey through a vast rep- At present, the orchestra’s home base is the recently ertoire of music, under the guidance of a long line of remodeled and acoustically impressive West Side Presby- skilled and devoted conductors. -

The Reception of Liszt's Faust Symphony in the United States

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2020 The Reception of Liszt’s Faust Symphony in the United States Chloe Danitz University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Danitz, Chloe, "The Reception of Liszt’s Faust Symphony in the United States" (2020). Masters Theses. 909. https://doi.org/10.7275/17489800 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/909 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Reception of Liszt’s Faust Symphony in the United States A Thesis Presented by CHLOE ANNA DANITZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2020 Music The Reception of Liszt’s Faust Symphony in the United States A Thesis Presented by CHLOE ANNA DANITZ Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Erinn E. Knyt, Chair __________________________________________ Marianna Ritchey, Member ______________________________________ Salvatore Macchia, Department Head Department of Music and Dance DEDICATION To my Grandparents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express the deepest gratitude to my advisor, Erinn Knyt, for her countless hours of guidance and support. Her enthusiasm and dedication to my research facilitated this project, as well as my growth as a musicologist. Her contributions to my professional development have been invaluable and will forever be appreciated. -

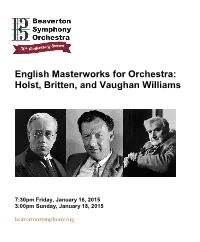

Beavert Symphony

BEAVERT SYMPHONY English Masterworks for Orchestra: Holst, Britten, and Vaughan Williams SVOBODA TCHAI 7:30pm Friday, January 16, 2015 3:00pm Sunday, January 18, 2015 beavertonsymphony.org Our guest Soloists Jen Harrison Les Green As the daughter of an opera singer and a music store owner it only followed that Jennifer Harrison would grow up to be a musician. Choosing the instrument which she felt possessed the most gorgeous tone, she began a life as a French horn player at the age of 11. As a teen she had the fortune of playing at the Tanglewood Music Festival in Massachusetts under the baton of Leonard Bernstein. After her college studies at Northwestern University, Jen played with the New Mexico Symphony for one year and thoroughly relished working as a symphonic player. Since moving to Portland she has been freelancing in the Portland area as a classical and even pop rock horn player. She is currently a member of the Portland Opera Orchestra, the Portland Chamber Orchestra, and the Portland Columbia Symphony Orchestra. During the month of December she performs with the Portland Brass Quintet in the annual Christmas Revels musical featuring songs and dances from centuries past. In the summertime Jen has been involved with the Sunriver Music Festival, the Bach Festival and the Astoria Music Festival. Jen also performs on occasion with the Oregon Symphony, the Oregon Ballet Theatre and the Eugene Symphony. Jen’s most unique musical endeavor is her creation of the Northwest Horn Orchestra, founded in 2007. This ensemble is the perfect fusion of her loves of both classical and pop genres spiced up with non-traditional theatrics. -

Boris Alexandrovich!

570195 bk Tchaikovsky US 13/11/06 08:24 Page 8 “Dear Boris Alexandrovich! Do not be vexed with the result of the exam. When I come back to Moscow, I will tell you the details of the discussion that ensued after listening Boris to your Symphony. There were interesting thoughts from some members of the examining board. As TCHAIKOVSKY for me, I am vexed with the results of the exam not less, but even more than you. Be steadfast and be the knight of the art. I believe in your Symphony No. 1 great composer’s talent. All that transpired convinced me even more that I am right... The Murmuring Forest Yours, After the Ball Dmitry Shostakovich” Volgograd Philharmonic Orchestra Letter from Dmitry Shostakovich to Boris Tchaikovsky (1947) after the Edward Serov exam where his First Symphony was displayed. At the threshold to 1948 the work did not receive the Saratov Conservatory highest grade from the examining board but made a profound Symphony Orchestra impression on Shostakovich. Kirill Ershov 8.570195 8 570195 bk Tchaikovsky US 13/11/06 08:24 Page 2 The Boris Tchaikovsky Society, a public non-profit organization, was Boris founded in Moscow in late 2002 and registered in 2003. Among the founders and members of the Society are composers, including pupils of Boris Tchaikovsky, musicologists and musical enthusiasts. The composer’s TCHAIKOVSKY widow, Yanina-Irena Iossifovna Moshinskaya, is also a founder of the (1925-1996) Society. The honorary members of the Society include Rudolf Barshai, Victor Pikaizen, Vladimir Fedoseyev, Edward Serov, and Karen Khachaturian. -

Brahms in Nineteenth-Century America

Brahms in Nineteenth-Century America Alison Deadman Ü :-. SEPTEMBER 7, 1866, Johannes's younger bro premiere of Brahms's Trio, No. I, in B majar, Op. ther Fritz ("the wrong Brahms") wrote their sister 8, at Dod\\orth's Rooms in New York, November from Caracas, suggesting that Johannes locate in 27, 1855. Significantly, this sole world premiere !O Venezuela, where the tropics '' ould profit his com have taken place in Amcrica is thc carliest reference positions.1 Howcver, unlike Anton Rubinstein, to Brahms's music in thc Unitcd Staces. William Tchaikovsky, Drni'ák, and Saint-Saens, Johannes Ma~on (b Bastan, 1829; d Ncw York, 1908) had ''as never to set foot in the Western Hemisphere; scudicd music extensivcly in Europc, firsc in Leipzig and onc hundrcd years after hi5 death it is the recep and Prague, and later in Weimar as a pupil of Franz tion history of his repertoire on the American stage Liszt. Himself present on the infamous occasion that now concerns us. "hen the young Brahm'> had dozed through Liszt 's performance, Masan recalls: Partly on account of the untoward Wcimar incident, and CHAMBER MUSIC partly for thc sake of hi~ º''º individuality, 1 took a peculiar interest in Brahm~. Hi'> work is wonderfully con Brahms first met the American public with his cham dcnsed, hi~ constructivc power, masterly .... But therc ber music, and it ''as his chambcr repenoire that are differences of opinion as regards his emotional sus began stimulating a divergencc of critica! opinan cepcibilitie!>, and it is just thi~ facl that pre,ents many that continued almost to the end of the century. -

Toronto Mandolin Orchestra Financial Support for the Programs Traditions to Thousands of Music at Trinity-St

NUMBER 77 OCTOBER 2014 626 BATHURST ST. TORONTO, ON ISSN-0703-9999 Community support is the life blood of Ensemble Each fall the National Shevchenko Without this support the Ensem- Musical Ensemble Guild of Cana- ble could not continue to bring In this issue … da appeals to the community for the finest of Ukrainian and other • Toronto Mandolin Orchestra financial support for the programs traditions to thousands of music at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre and further artistic development of lovers. the Shevchenko Musical Ensemble. Please give generously to this • Shevchenko Musical Ensemble’s Tribute to Taras Funds raised in this campaign Annual Sustaining Fund Drive. Shevchenko will guarantee that this unique Help maintain and further performing arts group will contin- develop one of Canada’s finest • Annual Banquet to honour ue to perpetuate the culture of its exponents of Ukrainian choral and Ruth Budd founders, blending this with the orchestral music. • John Boyd on the musical traditions of many other And by giving your support to eccentricities of the English Canadians. the Shevchenko Musical Ensemble language The performers in the Ensemble, you also become part of this One- • Choral Concert with tribute as well as volunteers on the Board of-a-Kind cultural experience. to the late Pete Seeger and other committees, freely give Thank you sincerely. of their time and talents to sustain this group. However, the life blood of a group such as ours is the support it receives from the community, from readers of the Bulletin who love and appreciate the cultural traditions preserved in the multi- cultural mosaic of Canada. -

Sir Ernest Macmillan Collection CA OTUFM 15

University of Toronto Music Library Sir Ernest MacMillan collection CA OTUFM 15 © University of Toronto Music Library 2020 Contents Sir Ernest MacMillan ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Ezra Schabas ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sir Ernest MacMillan collection ................................................................................................................... 3 Series A: Research files and correspondence ............................................................................... 3 Series B: Interviews conducted by Ezra Schabas ...................................................................... 21 Sir Ernest MacMillan collection University of Toronto Music Library CA OTUFM 15 Sir Ernest MacMillan 1893-1973 Sir Ernest MacMillan, conductor, organist, pianist, composer, educator, writer, administrator, was born in Mimico (Metropolitan Toronto) on August 18, 1893, and died in Toronto on May 6,1973. He was one of the most influential Canadian musicians of the middle 20th century. Ezra Schabas 1924- Prof. Ezra Schabas was born in New York and received his Diploma in Clarinet (1943) and Bachelor of Science (1948) from the Juillard School. In 1949, he received his Master of Arts from Columbia University. He also studied at the Conservatoire de Nancy, and the Fontainebleau School for the Arts in France -

ED116662.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 116 662 IR 002 905 TITLE Educational Materials Catalog. Bulletin 717, Revised 1975. INSTITUTION Texas Education Agency, Austin. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 490p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.92 HC-$24.75 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Audiovisual Aids; *Catalogs; Elementary Secondary Education; Filmstrips; Higher Education; Inservice Teacher Education; Instructional Films; *Instructional Media; Phonotape Recordings; Professional Continuing Education; Resource Centers; Slides; Teacher Education; Video Tape Recordings; Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *Texas ABSTRACT A catalog prepared by the Resource Center, Texas Educational Agency, provides information about audio and video tapes available for duplication and also about films, filmstrips, and slide-tape presentations available for free loan to Texas educational institutions. Programs cover all areas of the school curriculum from kindergarten through college as well as professional development and subjects appropriate for in-service education study groups. The major section lists audio tapes arranged by subject areas. The second section lists other media by type: filmstrips, 16mm films, slide-tape kits, and videotapes. Series are briefly annotated, as are some individual items. There is a title index.(Author/LS) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items -

Bmc News March 17 For

The Bellingham Music Club March 1, 2017, 10:30 a.m. Trinity Lutheran, 119 Texas St. The Newsletter of the Bellingham Music Club Recently, Sherrie Kahn and Mark Schlichting coordinated two of the four BMC competitions for high school students. On hand to offer useful advice and “high fives” were adjudicators Dr. Gustavo Camacho , Assistant Professor of Horn and Brass Area Coordinator at WWU, and Gerry Jon Marsh , Music Director and Conductor of the Cascade Youth Symphony. We applaud all the contestants, their parents and teachers, thank Sherrie, Mark, and awards chair, Charli Daniels , and are thrilled to present winners at today’s program. We congratulate them and hope our awards inspire them to further their talents. The BMC established the high school string competition three years ago to honor the legacy of Ethel Crook who was a violin teacher and orchestra director in Whatcom County from the 1940s though the 1990s. She was a founding member of what is now the Whatcom Symphony Orchestra, and BMC president between 1988 and 1992. While many of us remember her vividly (she passed away in 2007), fewer had a chance to know Nicholas Bussard . We asked Jack Frymire, who worked closely with him at the WSO, to draw a portrait. NǙǓǘǟǜǑǣ AǞǔǢǺ BǥǣǣǑǢǔ (1931-1997) He was mister music in Bellingham. — The Herald It comes as a shock to realize that Nicholas Bussard passed away 20 years ago, long before today's recipients of his namesake award were even born. It is too soon to speak of him in the past tense, when he is still so present in the lives of his family and friends, former history stu- dents at Sehome High School and oboe students at Western; too soon to forget those memorable musical collaborations with Nancy Bussard, his wife and fellow recipient of both the Mayor's Arts Award and the Alumni of Merit award from their alma mater, Whitman College.