European Architecture 1750-1890

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Edition

FREE August 27-September 2, 2020 • Vol. 46, No. 6 Fall Guide August 27-September 2, 2020 | Illinois Times | 1 2 | www.illinoistimes.com | August 27-September 2, 2020 OPINION Big guy, big personality, big flaws Former governor James Thompson dies DYSPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr. James R. Thompson, the biggest (six feet six) had his virtues as a chief executive. Not until and longest (14 years in office) governor Illinois the election of JB Pritzker has Illinois seen a ever had, died on Aug. 14, 2020, in Chicago at governor of Thompson’s intelligence (although 84. His rise as a politician coincided with that Pritzker came into office with a better education of this newspaper, and to those of us working at and broader experience). He was a quick study Illinois Times in those days he was a familiar, if and he realized that legislative politics was a often exasperating, character. matter of getting things done, not striking poses. Senate President Don Harmon observed, He saved the Dana-Thomas House for the “No one enjoyed being governor more.” public and saved the governorship for Jim Edgar, Certainly, no modern governor did. Inside the whom he hand-groomed for the job. big man was a little boy with a sweet tooth Unfortunately, he never dared enough to who in January 1977 found himself in his become one of Illinois’s great governors in the own candy shop. He ate it all up – the corn mold of Lowden or Horner or Ogilvie. Maybe dogs, the applause, the press attention, the that was just because he wasn’t interested enough chauffeured rides. -

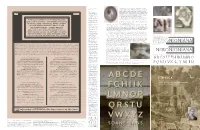

Etrvscan • Demonstrating the 7

DEVELOPMENT OF SERIF-LESS TYPE — TIMELINE SSTUVVW XYWUZa aSWbV ZSa cVUdcW ecYX IUfgh, RYiVcU MSgWV, f jcYXSaSWk Image rights and references: fcbZSUVbUlVWkSWVVc, cVbVSmVa f gVUUVc nfUVn: Røùú, Nøû. 11, 1760. ecYX ZSa Italy Fig: XVWUYc fWn ecSVWn GSYmfWWS BfUUSaUf PScfWVaS. TZV IUfgSfW fcbZSUVbUoa 1. (Left) Leonardo Agostini (1686) Le Gemme Antiche Fiurate. Engraving of a ‘Magic Gem’ of serif-less cVjdUfUSYW Zfn bYXV SWbcVfaSWkgh dWnVc fUUfbpVn ecYX FcVWbZ fcbZSUVbUa letterforms. Tav. Fig.52 [83] CARAERI MAGICI in lapis lazuli. © GIA Library Additional Collections (Gemological Institute of America), in the public domain. fWn gSUVcfch bcSUSba Ye UZV fcUa UZcYdkZYdU UZV 1750a. CgfaaSbfg RYXfW Emf. XX 1. (Right) Leonardo Agostini (1593-1669). Portrait aged 63, frontispiece from Le Gemme Antiche Fiurate, 1686. © GIA fcbZSUVbUdcV fa fW SnVfg qfa iVSWk bZfggVWkVn SW efmYdc Ye rUZV GcVVpo Library Additional Collections (Gemological Institute of America), in the public domain. 2. Dempster, Thomas (1579-1625). Coke, Thomas, Earl of qSUZSW qZfU iVbfXV pWYqW fa UZV GcfVbYlRYXfW nVifUV. Leicester, and Bounarroti, Filippo (1723). De Etruria Regali, III Libri VII, nunc primum editi curante Thomas Coke. Opus postumum. Florentiæ: Cajetanus Tartinius. Written in With some disdain he writes: “My Work ‘On the Magnificence of 1616-19. Liber Tertius, Tabulæ Eugubinæ. (viewer pp.693-702). Tabular I of V. © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, digital.onb.ac.at in the public domain. Architecture of the Romans’ has been finished some time since... it consists 3. (Left) Forlivesi, Padre Giovanni Nicola (Giannicola). From the Convent of San Marco in Corneto. The Augustinian of 100 sheets of letterpress in Italian and Latin and of 50 plates, the IN DCCLVI GIAMBAISTA PIRANESI RELEASED monk’s 14 written bulletins to Anton Francesco Gori with observational drawings and decipherment of Etruscan inscriptions at Tarquinia near Corneto, from 11th May to 4th whole on Atlas paper. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 CULTURAL METHODS OF MANIPULATING PLANT GROWTH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gary R. -

Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown. Architecture As Signs and Systems

Architecture as Signs and Systems For a Mannerist TIme Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS· CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS· LONDON, ENGLAND· 2004 Art & Arch e'J' ,) re Library RV: Washington u:'li \/(H'si ty Campus Box 1·,):51 One Brookin18 Dr. st. Lg\li,s, !.:0 &:n:W-4S99 DSB: RV, DSB: Copyright e 2004 by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown All rights reserved Printed in Italy Book Design by Peter Holm, Sterling Hill Productions Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Venturi, Robert. Architecture as and systems: for a mannerist time I Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. p. em. - (The William E. Massey, Sr. lectures in the history of American civilization) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-674-01571-1 (alk. paper) 1. Symbolism in architecture. 2. Communication in architectural design. I. Scott Brown, Denise, 1931- II. Title. ill. Series. NA2500.V45 2004 nO'.I-dc22 200404{)313 ttext," for show his l them in lied "that le most of 'espitemy to be an me of our 19 studies, mth these Architecture as Sign rather than Space ecause if I New Mannerism rather than Old Expressionism 1geswon't ROBERT VENTURI ,the com :tronger ::ople who . work and lity to the _~.'n.•. ~~~,'~'"'.".'."_~ ____'_''''"'«'''.'''''',_",_.""",~",-,-" ".,-=--_""~ __ , ..... """'_.~~"',.._'''''_..._,,__ *' ...,',.,..,..... __ ,u~.,_~ ... mghai, China. 2003 -4 -and for Shanghai, the mul A New Mannerism, for Architecture as Sign . today, and tomorrow! This of LED media, juxtaposing nbolic, and graphic images at So here is complexity and contradiction as mannerism, or mannerism as ing. -

Masterworks Architecture at the Masterworks: Royal Academy of Arts Neil Bingham

Masterworks Architecture at the Masterworks: Royal Academy of Arts Neil Bingham Royal Academy of Arts 2 Contents President’s Foreword 000 Edward Middleton Barry ra (1869) 000 Sir Howard Robertson ra (1958) 000 Paul Koralek ra (1991) 000 Preface 000 George Edmund Street ra (1871) 000 Sir Basil Spence ra (1960) 000 Sir Colin St John Wilson ra (1991) 000 Acknowledgements 000 R. Norman Shaw ra (1877) 000 Donald McMorran ra (1962) 000 Sir James Stirling ra (1991) 000 John Loughborough Pearson ra (1880) 000 Marshall Sisson ra (1963) 000 Sir Michael Hopkins ra (1992) 000 Architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts 000 Alfred Waterhouse ra (1885) 000 Raymond Erith ra (1964) 000 Sir Richard MacCormac ra (1993) 000 Sir Thomas Graham Jackson Bt ra (1896) 000 William Holford ra, Baron Holford Sir Nicholas Grimshaw pra (1994) 000 The Architect Royal Academicians and George Aitchison ra (1898) 000 of Kemp Town (1968) 000 Michael Manser ra (1994) 000 Their Diploma Works 000 George Frederick Bodley ra (1902) 000 Sir Frederick Gibberd ra (1969) 000 Eva M. Jiricna ra (1997) 000 Sir William Chambers ra (1768, Foundation Sir Aston Webb ra (1903) 000 Sir Hugh Casson pra (1970) 000 Ian Ritchie ra (1998) 000 Member, artist’s presentation) 000 John Belcher ra (1909) 000 E. Maxwell Fry ra (1972) 000 Will Alsop ra (2000) 000 George Dance ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Richard Sheppard ra (1972) 000 Gordon Benson ra (2000) 000 no Diploma Work) 000 Sir Reginald Blomfield ra (1914) 000 H. T. Cadbury-Brown ra (1975) 000 Piers Gough ra (2001) 000 John Gwynn ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Ernest George ra (1917) 000 no Diploma Work) 000 Ernest Newton ra (1919) 000 Ernö Goldfinger ra (1975) 000 Sir Peter Cook ra (2003) 000 Thomas Sandby ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Edwin Lutyens pra (1920) 000 Sir Philip Powell ra (1977) 000 Zaha Hadid ra (2005) 000 bequest from great-grandson) 000 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott ra (1922) 000 Peter Chamberlin ra (1978) 000 Eric Parry ra (2006) 000 William Tyler ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir John J. -

Mannerism COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

ABPL 702835 Post-Renaissance Architecture Mannerism COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice perfection & reaction Tempietto di S Pietro in Montorio, Rome, by Donato Bramante, 1502-6 Brian Lewis Canonica of S Ambrogio, Milan, by Bramante, from 1492 details of the loggia with the tree trunk column Philip Goad Palazzo Medici, Florence, by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo, 1444-59 Pru Sanderson Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara, by Biagio Rossetti, 1493 Pru Sanderson Porta Nuova, Palermo, 1535 Lewis, Architectura, p 152 Por ta Nuova, Pa lermo, Sic ily, 1535 Miles Lewis Porta Nuova, details Miles Lewis the essence of MiMannerism Mannerist tendencies exaggerating el ement s distorting elements breaking rules of arrangement joking using obscure classical precedents over-refining inventing free compositions abtbstrac ting c lass ica lfl forms suggesting primitiveness suggesting incompleteness suggesting imprisonment suggesting pent-up forces suggesting structural failure ABSTRACTION OF THE ORDERS Palazzo Maccarani, Rome, by Giulio Romano, 1521 Heydenreich & Lotz, Architecture in Italy, pl 239. Paolo Portoghesi Rome of the Renaissance (London 1972), pl 79 antistructuralism -

Boletín Museo E Instituto Camón Aznar

BOLETÍN MUSEO E INSTITUTO CAMÓN AZNAR N.º 116 • 2018 MUSEO E INSTITUTO CAMÓN AZNAR DE IBERCAJA Premio “Europa Nostra” 1980. Medalla de Honor de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, 1981. Premio Accesibilidad 2002 que concede Disminuidos Físicos de Aragón y el Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Aragón. BOLETÍN MUSEO E INSTITUTO CAMÓN AZNAR DE IBERCAJA Nº 116 • 2018 PUBLICACIONES DEL MUSEO E INSTITUTO CAMON AZNAR Fundación Ibercaja DIRECCIÓN María Rosario Añaños Alastuey CONSEJO EDITOR: Esther Almarcha (Universidad de Castilla La Mancha), Luis Arciniega (Universitat de València), Pilar Biel (Universidad de Zaragoza), Alberto Castán (Universidad de Zaragoza), María Cruz de Carlos Varona (Museo Nacional del Prado), Benoit de Tapol (Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya), Ascensión Hernández (Universidad de Zaragoza), Carmen Morte (Universidad de Zaragoza), Wifredo Rincón (CSIC), Claudio Varagnoli (Università degli Studi G. D’Annunzio Chieti-Pescara) COMITÉ CIENTÍFICO: Ana Ágreda (Universidad de Zaragoza), Begoña Arrúe (Universidad de La Rioja), Miriam Alzuri (Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao), Elena Barlés (Universidad de Zaragoza), Jesús Criado (Universidad de Zaragoza), Pilar García (Universidad de Oviedo), Cristina Giménez (Universidad de Zaragoza), Pedro Luis Hernando (Universidad de Zaragoza), Concepción Lomba (Universidad de Zaragoza), Jesús Pedro Lorente (Universi- dad de Zaragoza), Juan Carlos Lozano (Universidad de Zaragoza), Amparo Martínez (Universidad de Zara- goza), Pilar Mogollón (Universidad de Extremadura), Leticia -

Allerton Park and Conference Center

GUIDE TO THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS' DOCUMENTATION RELATED TO THE ALLERTON FAMILY AND ROBERT ALLERTON PARK AND CONFERENCE CENTER Compiled by Susan Enscore For the Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign January 1991 Revised March 2004 Reformatted for Internet Posting, October, 2001 FOREWORD Since Robert Allerton gave his estate in Monticello to the University in 1946, the number and diversity of documents and related materials on this unique resource has grown steadily. By far the most ambitious and comprehensive attempt to identify and catalog major items is represented in this document which is the product of over a year's effort by Susan Enscore. Her work was carefully guided by Professors Maynard Brichford and William Maher, the University's archivist and assistant archivist. As interim co-directors, we commissioned this project to learn more about how much "Allertonia" exists and where it can be found. The size of this report confirms our suspicions that a wealth of useful material is available. A great deal of effort was involved in assembling this impressive reference document. It identifies the variety of documents that exist and their location, as well as serving as the basis for further expansion and update of the records of Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center. Researchers interested in examining the history associated with this gift will find this a valuable reference source. We appreciate all of Susan's work and the enthusiasm with which she approached the task. We thank Professors Brichford and Maher who added their experience to producing a well-organized and comprehensive document. -

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 18 April 2011 i) CONTENTS PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 0 Purpose of the Appraisal ............................................................................................................ 2 Designation................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 4 3.0 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST........................................................................................ 5 Context and Evolution................................................................................................................ 5 Spatial Character and Views ...................................................................................................... 6 Building Typology and Form....................................................................................................... 8 Prevalent and Traditional Building Materials ............................................................................ 10 Characteristic Details................................................................................................................ 10 Landscape and Public Realm.................................................................................................. -

YALE in LONDON – SUMMER 2013 British Studies 189 Churches: Christopher Wren to Basil Spence

YALE IN LONDON – SUMMER 2013 British Studies 189 Churches: Christopher Wren to Basil Spence THE CHURCHES OF LONDON: ARCHITECTURAL IMAGINATION AND ECCLESIASTICAL FORM Karla Britton Yale School of Architecture Email: [email protected] Class Time: Tuesday, Thursday 10-12:15 or as scheduled, Paul Mellon Center, or in situ Office Hours: By Appointment Yale-in-London Program, June 10-July 19, 2013 Course Description The historical trajectories of British architecture may be seen as inseparable from the evolution of London’s churches. From the grand visions of Wren through the surprising forms of Hawksmoor, Gibbs, Soane, Lutyens, Scott, Nash, and others, the ingenuity of these buildings, combined with their responsiveness to their urban environment, continue to intrigue architects today. Examining the ecclesiastical architecture of London beginning with Christopher Wren, this course critically addresses how prominent British architects sought to communicate the mythical and transcendent through structure and material, while also taking into account the nature of the site, a vision of the concept of the city, the church building’s relationship to social reform, ethics, and aesthetics. The course also examines how church architecture shaped British architectural thought in the work of historians such as Pevsner, Summerson, Rykwert, and Banham. The class will include numerous visits in situ in London, as well as trips to Canterbury, Liverpool, and Coventry. Taking full advantage of the sites of London, this seminar will address the significance of London churches for recent architects, urbanists, and scholars. ______________________________________________________________________________________ CLASS REQUIREMENTS Deliverables: Weekly reflection papers on the material covered in class and site visits. Full participation and discussion is required in classroom and on field trips. -

Allerton Park Climate Action Plan (Apcap)

apCAP: A Climate Action Plan for Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign V 2 Oct 2013 apCAP V.2 Oct 2013 Executive Summary In 2008, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign signed the American College & University Presidents' Climate Commitment. This action committed the campus to carbon neutrality by the year 2050. It also lead to the development of the Illinois Climate Action Plan (iCAP), a detailed plan that lays out strategies for achieving the 2050 commitment. Inspired by this pledge and as a part of the iCAP, Allerton Park has created the following Allerton Park Climate Action Plan (apCAP). This Plan is created to assist in meeting the University’s iCAP climate commitments by describing the Park’s role in the path toward carbon neutrality on a localized scale. As a leading entity in campus environmental conservation and sustainability and a valued asset within the state of Illinois, the Park plays an important role as a model for the campus community, state conservation areas, and historic properties. This Plan represents a roadmap for a climate neutral future at Allerton, it outlines strategies, initiatives, and targets toward meeting the goal of carbon neutrality by 2035. apCAP A vibrant teaching, recreational, and natural areas sanctuary for nearly 100,000 visitors each year, Allerton Park is a unique cultural and environmental asset for the University of Illinois. It serves as a bridge between the public, resource conversation, and the educational and research resources of the University. It also provides a learning laboratory for the demonstration of sustainable technologies to educate and prepare individuals with skills required to tackle the challenges of a sustainable society – as envisioned by the University of Illinois’ Strategic Plan. -

Sophie's World

Sophie’s World Jostien Gaarder Reviews: More praise for the international bestseller that has become “Europe’s oddball literary sensation of the decade” (New York Newsday) “A page-turner.” —Entertainment Weekly “First, think of a beginner’s guide to philosophy, written by a schoolteacher ... Next, imagine a fantasy novel— something like a modern-day version of Through the Looking Glass. Meld these disparate genres, and what do you get? Well, what you get is an improbable international bestseller ... a runaway hit... [a] tour deforce.” —Time “Compelling.” —Los Angeles Times “Its depth of learning, its intelligence and its totally original conception give it enormous magnetic appeal ... To be fully human, and to feel our continuity with 3,000 years of philosophical inquiry, we need to put ourselves in Sophie’s world.” —Boston Sunday Globe “Involving and often humorous.” —USA Today “In the adroit hands of Jostein Gaarder, the whole sweep of three millennia of Western philosophy is rendered as lively as a gossip column ... Literary sorcery of the first rank.” —Fort Worth Star-Telegram “A comprehensive history of Western philosophy as recounted to a 14-year-old Norwegian schoolgirl... The book will serve as a first-rate introduction to anyone who never took an introductory philosophy course, and as a pleasant refresher for those who have and have forgotten most of it... [Sophie’s mother] is a marvelous comic foil.” —Newsweek “Terrifically entertaining and imaginative ... I’ll read Sophie’s World again.” — Daily Mail “What is admirable in the novel is the utter unpretentious-ness of the philosophical lessons, the plain and workmanlike prose which manages to deliver Western philosophy in accounts that are crystal clear.