Submission Cover Sheets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airport City Developments in Australia : Land Use Classification and Analyses

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Walker, Arron R. and Stevens, Nicholas J. (2008) Airport city developments in Australia : land use classification and analyses. In: 10th TRAIL Congress and Knowledge Market, 14-15 October 2008, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. © Copyright 2008 [please consult the authors] Airport city developments in Australia Land use classification and analyses TRAIL Research School, Delft, October 2008 Authors Dr. Arron Walker, Dr. Nicholas Stevens Faculty of Built Environment and Engineering, School of Urban Development, Queensland University of Technology, Qld, Australia © 2008 by A. Walker, N. Stevens and TRAIL Research School Contents Abstract 1 Introduction.......................................................................................................1 2 Background........................................................................................................2 2.1 Aviation growth in Australia...............................................................................2 2.2 Airport ownership in Australia ...........................................................................3 2.3 Airport Planning under Airports Act 1996 .........................................................4 2.4 Diversification of airport revenue.......................................................................5 3 Land use analysis: methods and materials .....................................................5 -

Loss of Control, Clyde North, Vic., 23 February 2007, Van's Aircraft Inc

ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Aviation Occurrence Investigation – 200701033 Final Loss of Control Clyde North, Victoria 23 February 2007 Van’s Aircraft Inc. RV-4, VH-ZGH ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Aviation Occurrence Investigation 200701033 Final Loss of Control Clyde North, Victoria 23 February 2007 Van’s Aircraft Inc. RV-4, VH-ZGH Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 - i - Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office location: 15 Mort Street, Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory Telephone: 1800 621 372; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6440 Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117; from overseas + 61 2 6247 3117 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2008. This work is copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may copy, download, display, print, reproduce and distribute this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice). However, copyright in the material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, you must not make any other use of the material in this publication unless you have the permission of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Please direct requests for further information or authorisation to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 www.ag.gov.au/cca ISBN and formal report title: see ‘Document retrieval information’ on page iii. -

Avalon Airspace Review 2019

Avalon Airspace Review December 2019 Office of Airspace Regulation Page 2 of 44 File Reference: FO18/1007 Document Reference: D19/48884 Document control: Version Issue/Nature of Revision Date 0.1 Initial January 2019 0.2 First draft revision February 2019 0.3 Second draft revision March 2019 0.4 Incorporates peer feedback July 2019 0.5 Incorporates Management feedback & update data September 2019 0.6 Branch Manager review October 2019 0.7 Airservices Australia review December 2019 Avalon Airspace Review – 2019 Version: 0.7 Office of Airspace Regulation Page 3 of 44 Executive Summary The Airspace Act 2007 (Act) provides the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) with authority to administer and regulate Australian-administered airspace and authorises CASA to undertake regular reviews of existing airspace arrangements. The Office of Airspace Regulation (OAR) has conducted an airspace review within a 15 nautical mile (NM) radius of Avalon Airport to determine if the airspace remains fit for purpose. The review examined the airspace architecture, classifications, procedures and infrastructure from the surface to 8,500 feet (FT) above mean sea level (AMSL). The previous aeronautical study specifically for Avalon was conducted in 2008.1 This airspace review applies CASA’s regulatory philosophy which considers the primacy of air safety, whilst taking into account the environment, security, cost and is consistent with the Australian Airspace Policy Statement 2018 and the Minister’s Statement of Expectations. A multifaceted approach was used in conducting this review, including quantitative and qualitative analysis consisting of: • Aerodrome traffic data; • Airspace design; • Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) incident data; and • Stakeholder consultation. -

Connecting the Bendigo Region to Melbourne Airport

Connecting the Bendigo region to Melbourne Airport For the first time passengers along the Bendigo Line will be able to catch a train to Melbourne Airport, with a single interchange at Sunshine Station. Bendigo Kangaroo Flat Harcourt To and from Melbourne Airport Bendigo Castlemaine — Seamless interchange between V/Line and airport services at Sunshine. KangarooMalmsbury Flat — Trains running from Sunshine to Melbourne KynetonHarcourt Airport every 10 minutes. CastlemaineWoodend — Easy access for interstate and international Macedon visitors, with a journey time from Melbourne Malmsbury Airport to Bendigo of around two hours. Gisborne Kyneton Melbourne Riddells Creek Airport ClarkefieldWoodend To CBD SunburyMacedon via Metro Tunnel WatergardensGisborne Melbourne Riddells Creek Sunshine Southern Airport Clarkefield Cross To CBD Sunbury via Metro Tunnel Legend Watergardens Melbourne Airport Rail Sunbury, Cranbourne and Pakenham (Metro Tunnel) Sunshine Southern Regional connections Cross Project timeline Legend Further engagementMelbourne Airport and detailed Rail planningSunbury, and development Cranbourne and Pakenham (Metro Tunnel) Regional connections 2020 onwards 2020-2021 2022 2029 Community and Statutory planning Construction Target stakeholder approval process commencement* opening engagement Market engagement date* Business case and Procurement process design development *Subject to relevant Victorian and Federal planning, environmental and other government approvals. About Melbourne Airport Rail Melbourne Airport Rail The Australian and Victorian The final project budget will be governments have agreed that confirmed once all major contracts is a transformational Melbourne Airport Rail will run on are awarded, with construction to public transport project dedicated, new tracks from a new begin in 2022 and a target opening premium station at Melbourne date for Melbourne Airport Rail connecting Melbourne Airport to Sunshine Station, where of 2029. -

MINUTES AAA Victorian Division Meeting

MINUTES AAA Victorian Division Meeting Tuesday 30 August 2016 8.30-16:30 Stamford Plaza Melbourne, 111 Little Collins Street, Melbourne 1. Welcome and Apologies Paul Ferguson (Chair) opened the meeting and welcomed members, thanking them for their attendance. New members were welcomed including Moira Shire Council (Yarrawonga Aerodrome) and three corporate members; Briggs Communications, JJ Ryan Consulting and Ubimet. Cate Anderson was introduced and welcomed as AAA Policy and Communications Officer. All actions arising have been completed. The sole action from the March 16 Division meeting was to distribute the meeting minutes which was completed. No formal correspondence was received. Attendees and apologies are set out below (the attendees list has been prepared based on the attendance sheet signed by attendees at the meeting). Presentations authorised for distribution are attached to the minutes. Members seeking additional information should contact the presenters directly. ATTENDEES Marianne Richards AAA Guest Matt Smale Air BP Leigh Robinson Airport Equipment Martin Chlupac Airport Lighting Specialists Ra Manuera Airport Lighting Specialists Kent Quigley Airservices Patrick Cui Airservices Australia David Young Arup Cate Anderson Australian Airports Association Nick Lane Australian Airports Association Simon Bourke Australian Airports Association Ken Keech Avalon Airshow Jill Brix Avisure Pty Ltd Roger Druce Bacchus Marsh Aerodrome Joseph Walsh Beca Anthony Perizzolo Boral Allan Briggs Briggs Communications Phil McConnell Cloud -

Moorabbin Airport Master Plan Implementation Framework

Part B Moorabbin Airport Master Plan Implementation Framework 107 108 The Moorabbin Airport Master Plan is divided into two 1 Implementation Framework distinct sections: Structure 110 ■ Part A Moorabbin Airport Master Plan Context; and 1.1 Implementation Framework Structure 111 ■ Part B Moorabbin Airport Master Plan Implementation 1.2 Land Use and Development Approvals 112 Framework 1.3 Approvals Process 113 Part A describes the Airport and the practical and 2 Land Use Policy 116 policy frameworks within which it operates. It includes a description of the existing operation at the Airport and 2.1 Strategic Policy Considerations 117 likely changes in the nature and form of aviation and 2.2 Vision and Objectives 117 other activity at the Airport. It sets out the context of the 2.3 Land Use Strategy 118 airport in relation to strategic policy at local, regional and state level. 3 Precinct Policy 120 3.1 Precinct A – Airside Operations 122 This part (Part B) sets out the framework within which decision making about future activity at the Airport 3.2 Precinct B – Airport Support Services 124 is made. This part articulates the Moorabbin Airport 3.3 Precinct C – Existing Retail & Commercial 126 Corporation’s (MACs) vision for the Airport in the form of 3.4 Precinct D – Industrial, Office, Retail, a Land Use Policy and includes controls and decision Commercial and Aviation Support 128 making criteria for land use and development at the 3.5 Precinct E – Business and Commercial Airport. including Aviation Support 130 4 Land Use and Development -

Collision with Terrain Involving Cessna 182, VH-KKM, 19 Km WSW Of

InsertCollision document with terrain title involving Cessna 182, VH-KKM Location19 km WSW | Date of Mount Hotham Airport, Victoria | 23 October 2013 ATSB Transport Safety Report Investigation [InsertAviation Mode] Occurrence Occurrence Investigation Investigation XX-YYYY-####AO-2013-186 Final – 16 April 2015 Cover photo: Aircraft owner Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 (24 hours) Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. -

Industry Guidelines Ports of Entry (Airports and Maritime)

Industry Guidelines Ports of Entry (Airports and Maritime) 19 March 2021 Ports of entry (airports and maritime) Victoria moved to COVIDSafe settings from 11:59pm on Friday 26 February 2021, and updates were made to restrictions at 11:59pm on Monday 15 March 2021. These restrictions will be reviewed regularly, to ensure they reflect current public health advice. All businesses must have a completed COVIDSafe Plan for each workplace to continue operating in Victoria. Ports of entry servicing international arrivals have additional obligations as determined by the Workplace Additional Industry Obligations Directions which apply to all ports of entry workplaces (including airports and maritime ports) where ports of entry workers and contractors are employed or engaged. This document provides advice to those employers and workers on how to limit the potential for transmission of COVID-19 and outline how ports of entry may continue to operate in a COVIDSafe way. Which locations are covered by these Guidelines? Ports Airports Port of Melbourne Melbourne Airport Port of Geelong Avalon Airport Port of Portland Essendon Airport Port of Hastings Jet Base Melbourne Which workers are covered by these Guidelines? A port of entry worker means: any airport or maritime port worker who has direct contact with international passengers or crew (excluding international passengers and crew entering Victoria from a Green Zone Country) at the international port of entry, including occasional contact or interactions; or a worker or person who interacts with the environment within the international port of entry where international passengers and crew are or have been, which includes any worker or person who boards a vessel, ship or aircraft. -

Avalon Airport Rail Link

AVALON AIRPORT RAIL LINK Planning study findings and public exhibition Introduction Avalon Airport Rail Link is a proposed rail link connecting Avalon Airport with Melbourne and Geelong. The rail link will help support Avalon to become Victoria’s second international passenger airport, ensuring that Victoria remains competitive into the future. Study purpose Reservation of the rail link corridor The rail link design has been developed to between the Melbourne – Geelong accurately define the proposed corridor. This planning study is being undertaken rail line and Avalon Airport is being to identify and protect a reservation for implemented by amendment to the Bridge structures will provide rail- a future rail link to the airport. Greater Geelong Planning Scheme to over-road grade separations at Old introduce a Public Acquisition Overlay. Melbourne Road, Princes Freeway and Beach Road. No permanent Background waterways will be crossed but the design would accommodate areas of Situated 20 km north-east of the City Project need temporary ponding after heavy rain, of Geelong and 55 km south-west of The rail link is part of an integrated using culverts or other infrastructure. Melbourne, Avalon Airport is a fully plan to ensure that Victoria is well operational commercial airline facility positioned in the future to cater for The rail link will terminate at a station to with an operating domestic airline the expected growth in air travel. be constructed adjacent to the existing terminal and a runway capable of passenger terminal area of the airport. receiving aircraft up to A380. With the The Victorian Government is planning support of government, the private for a population of more than 10 million operator Avalon Airport Australia Pty people by 2051, including 7.8 million Transport services Ltd is working to secure an international people in Greater Melbourne. -

Essendon Fields Precinct – Hyatt Place Melbourne

insert cover positional here MELBOURNE CBD about this 15 minutes box size 10% Transparency of your 16 DFO ESSENDON cover artwork Tullamarine Freeway & CityLink TRA N S P O R T A BOUT U S 15 iFLY THINGS TO D O F OOD & DRINK 6 ESSENDON FIELDS AIRPORT 7 GYMNASIUM S ERVICE S 9 ESSENDON FIELDS CENTRAL 12 LAMANNA CAFÉ & SUPERMARKET ue ven 1 THE HUNGRY FOX CAFÉ ve A Hargra Bristol Street 2 CAR DEALERSHIPS MELBOURNE AIRPORT 3 FLIGHT EXPERIENCES 8 CHILDCARE 11 DENTIST 7km* 4 AIRWAYS MUSEUM 13 HYATT PLACE HOTEL & EVENTS CENTRE CYCLING TRAIL 5 BOUNCE INC. TRAM STOP 56 10 MEDICAL CENTRE English Street ESSENDON STATION oad Nomad R levard kin Bou Lar ESSENDON FIELDS IS WELL CONNECTED TO BOTH THE BUSINESS DISTRICT MELBOURNE CBD AND 14 MR MCCRACKEN RESTAURANT & BAR MELBOURNE AIRPORT MELBOURNE CBD 10km* Public Transport The free EF Station Shuttle operates from Essendon Fields to Essendon Train Station. Every weekday departing on the half hour between 7.15 – 9.30am & 4.15 – 6.30pm. Tram service 59 is a short walk from EF. Stop 56 (Airport West), located on Matthews Ave/ Earl Street departs every 8 minutes. Myki available from EF Newsagency. Airport Transit 16 DFO Essendon The free airport shuttle bus operates on- DFO Essendon comprises over 110 outlet retailers including demand daily between Essendon Fields Polo Ralph Lauren, Hugo Boss, Ted Baker and Coach. The Airport and Melbourne Airport between adjacent Homemaker Hub comprises over 20 stores. 6.00am and 10.00pm. Visit ef.com.au/ 100 Bulla Road, Essendon airportshuttle for booking details. -

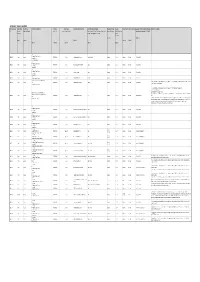

The Table of Services (PDF)

APPENDIX 1: TABLE OF SERVICES Proposed Service Contract type Availability Brief Service Description Airframe Aircraft Type Nominated Operational Base Firebombing Delivery System Passenger Carriage Fuelling Service Period Approximate timing Specimen Contract applicable Schedules Additional Information ID Primary / Absolute / Partial RW / FW Type 1 / Type 2 / Type 3 Tank / Bucket / (Bucket) / Long line bucket / Tank or Required / Optional Wet-A Hire / Wet- (in addition to Schedules 1, 2, 3,4, & 5) Secondary bucket / Tank (preferred) or Bucket B Hire / Dry Hire (Note 7) (Note 11) (Note 1) (Note 2) (Note 5) (Note 9) (Note 10) (Note 3) (Note 4) (Note 4) (Note 6) (Note 8) AAS Firefighter & Cargo Transport RW21302 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Moorabbin Airport, Victoria Bucket (Optional) Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules A & B Burning (Note 14) Firebombing (optional) AAS Firefighter & Cargo Transport RW21303 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Ovens helibase, Victoria (Note A) Bucket Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules A & B Firebombing Burning (Note 14) AAS Firefighter & Cargo Transport RW21304 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Bairnsdale, Victoria Bucket Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules A & B Firebombing Burning (Note 14) AAS RW21305 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Bendigo Airport, Victoria (Bucket) Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules B Burning (preferred) (Note 14) Airborne Information Gathering (AIG) (Note 16) This Service requires a specific configuration to support regular 'airborne information gathering' operations (Refer to Section 2.1 of Part B RW21307 Primary Absolute AAS ROTARY WING Type 3 Moorabbin Airport, Victoria (Bucket) Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules B & C in the Invitation to Tender document). -

TTF Rapid Buses, Road & Rail (Melbourne Airport)

RAPID BUSES, ROAD AND RAIL GROUND TRANSPORT SOLUTIONS TO MEET MELBOURNE AIRPORT’S PASSENGER GROWTH TO 2050 JULY 2013 Membership of Tourism & Transport Forum Tourism & Transport Forum (TTF) is a national, member-funded CEO forum, advocating the public policy interests of 200 leading corporations and institutions in the Australian tourism, transport, aviation and investment sectors For further information please contact: Justin Wastnage | Director, Aviation Policy | [email protected] Martin Gray | Policy Officer |[email protected] Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 4 Ensuring transport choice for Melbourne Airport ................................................................ 4 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 6 List of figures ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 MELBOURNE AIRPORT – THE NEXT 30 YEARS ............................................................ 7 Forecast demand .................................................................................................................... 7 ACCESSING MELBOURNE AIRPORT .......................................................................... 8 Internal airport transport ......................................................................................................... 8 Broader road network ............................................................................................................