Finalgen Revisited: New Discoveries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

This Multi-Media Resource List, Compiled by Gina Blume Of

Delve Deeper into Brooklyn Castle A film by Katie Dellamaggiore This list of fiction and Lost Generation-- and What Eight-time National Chess nonfiction books, compiled We Can Do About It. New Champion as a youth and by Erica Bess, Susan Conlon York: Harper Perennial, subject of the film Searching for and Hanna Lee of Princeton 2013. Froymovich discusses the Bobby Fischer (1993), Josh Public Library, provides a impact of the 2008 recession on Waitzkin later expanded his range of perspectives on the millennials (defined as people horizons and studied martial issues raised by the POV being born between 1976 and arts, eventually earning several documentary Brooklyn 2000) and presents ideas such National and World Castle. as political activism and creative Championship titles. In this entrepreneurship as potential book, he shares his personal Brooklyn’s I.S. 318, a solutions to the long-term side journey to the top—twice—and powerhouse in junior high chess effects of financial crisis. his reflections on principles of competitions, has won more learning and performance. than 30 national championships, Kozol, Jonathan. Savage the most of any school in the Inequalities: Children in Weinreb, Michael. The Kings country. Its 85-member squad America’s Schools. New of New York: A Year Among boasts so many strong players York: Crown, 1991. National the Geeks, Oddballs, and that the late Albert Einstein, a Book Award-winning author Geniuses Who Make Up dedicated chess maven, would Jonathan Kozol presents his America’s Top High School rank fourth if he were on the shocking account of the Chess Team. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3

01-01 Cover - October 2020_Layout 1 18/09/2020 14:00 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Peter Wells.......................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine The acclaimed author, coach and GM still very much likes to play Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Online Drama .........................................................................................................8 Danny Gormally presents some highlights of the vast Online Olympiad Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Carlsen Prevails - Just ....................................................................................14 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Nakamura pushed Magnus all the way in the final of his own Tour 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Find the Winning Moves.................................................................................18 3 year (36 issues) £125 Can you do as well as the acclaimed field in the Legends of Chess? Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Opening Surprises ............................................................................................22 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 -

Chess Book List

A treat for you all to start the New Year. Happy New Year to you all and I hope some of these books make you better chess players. Here is the next book list I told you about a few weeks ago. All are books on the Opening. All prices are in Canadian funds and postage will be added to your order. Any payment method is acceptable but please note that if you wish to use your credit card you can do so via PayPal. To do this I will send an invoice to you and you will follow the instructions sent to you from PayPal. Paying this way is quick and easy but it will cost you 4% more. This is the fee Paypal charges me for using their services. A personal cheque or money order will not cost you anything more than the actual book costs plus postage. As always first come-first served so if you see something you want please order promptly to avoid disappointment. If you ordered something from the first list I will combine shipping to save you some postage. Please note that # 1 to # 134 have been already offered and sent to all CCCA members during January. If you have email and did not receive these messages it is because I do not have your address or the address I have on file for you is no longer functioning. I suggest you contact me so I can correct this situation. My email is [email protected]. Please note that I added # 135 to 150 just so you email members can have something new to look at. -

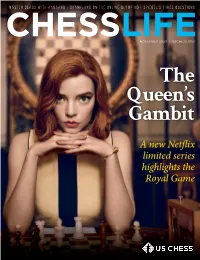

The Queen's Gambit

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

Magnus Carlsen and Peter Heine Nielsen at the St

FREE EXCERPT FROM ISSUE 2019#8 ALPHAZERO The exciting impact of a game changer When Magnus met AlphaZero LENNART OOTES Magnus Carlsen and Peter Heine Nielsen at the St. Louis Chess Club. It’s been a great year for the World Champion and the head of his analytical team, not in the last place thanks to the inspiration of AlphaZero. AlphaZero’s play has sent shockwaves through the chess world. Magnus Carlsen even confessed that he has become a different player thanks to the inspiration of the revolutionary engine (and Daniil Dubov). PETER HEINE NIELSEN looks back on a wonderful year for the World Champion and the role AlphaZero played in his successes. 2 A ALPHAZERO magine a spaceship information, curious chess players Championship match between landing in the centre obviously read the smallest details, Magnus and Fabiano Caruana to of London, friendly looking to extract as much knowl- finish before publishing the paper, I aliens having a quick edge as they could. not risking that some novelty played look at the tourist attractions and The following formula: by AlphaZero would influence the then quietly leaving again. Apart match. (p, v) = f (s), l = (z – v)2 – πT log p + c||0||2 from the initial shock, I assume life 0 Again they were beautiful games, would resume its normal course, is explained at great length, but interesting novelties and expla- except for the fact that we would I think it left us just as wise as non- nations of AlphaZero’s ‘thought- seriously have to question our tech- chess players reading chess notation. -

The Queen's Gambit

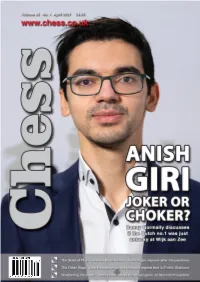

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

CHESS-Nov2011 Cbase.Pdf

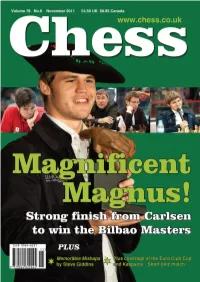

November 2011 Cover_Layout 1 03/11/2011 14:52 Page 1 Contents Nov 2011_Chess mag - 21_6_10 03/11/2011 11:59 Page 1 Chess Contents Chess Magazine is published monthly. Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial Editor: Jimmy Adams Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in chess 4 Acting Editor: John Saunders ([email protected]) Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Readers’ Letters ([email protected]) You have your say ... Basman on Bilbao, etc 7 Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Sao Paulo / Bilbao Grand Slam 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 The intercontinental super-tournament saw Ivanchuk dominate in 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Brazil, but then Magnus Carlsen took over in Spain. 8 3 year (36 issues) £125.00 Cartoon Time Europe Oldies but goldies from the CHESS archive 15 1 year (12 issues) £60.00 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Sadler Wins in Oslo 3 year (36 issues) £165.00 Matthew Sadler is on a roll! First, Barcelona, and now Oslo. He annotates his best game while Yochanan Afek covers the action 16 USA & Canada 1 year (12 issues) $90 London Classic Preview 2 year (24 issues) $170 We ask the pundits what they expect to happen next month 20 3 year (36 issues) $250 Interview: Nigel Short Rest of World (Airmail) Carl Portman caught up with the English super-GM in Shropshire 22 1 year (12 issues) £72 2 year (24 issues) £130 Kasparov - Short Blitz Match 3 year (36 issues) £180 Garry and Nigel re-enacted their 1993 title match at a faster time control in Belgium. -

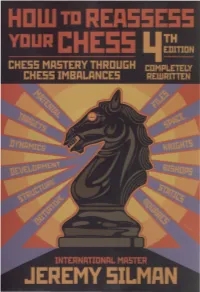

Jeremy-Silman-How-To-Reassess

HOW TD REA55E55 YDUR CHE55 �=TIDN Copyright© 2010 by Jeremy Silman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. First Edition 10 98765 4321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silman, Jeremy. How to reassess your chess : chess mastery through chess imbalances I by Jeremy Silman. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-890085-13-1 (alk. paper) 1. Chess. I. Title. GV1449.5.S553 2010 794.1 '2--dc22 2010042391 ISBN 978-1-890085-14-8 (cloth) Distributed in Europe by New In Chess www.newinchess.com Cover design and photography by Wade Lageose for Lageose Design SIL{S PRfSS 3624 Shannon Road Los Angeles, CA 90027 The first edition ofHow to Reassess Your Chess was dedicated to Mr. Steven Christopher, who encouraged me to share my teaching ideas with the chess public. It seems onlyfitting that this final edition should also bear this extremely kind man's name. Preface xz Acknowledgements xu Introduction xm Part One /The Concept of Imbalances 1 Imbalances I Learning the ABCs 3 Superior Minor Piece- Bishops vs. Knights 4 Pawn Structure- Weak Pawns, Passed Pawns, etc. 5 Space-The Annexation of Territory 6 Material-The Philosophy of Greed 7 Control of a Key File- Roads for Rooks 8 Control of a Hole/Weak Square- Homes for Horses 8 Lead in Development- You're Outnumbered! 9 Initiative- Calling the Shots 10 King Safety- Dragging Down the Enemy Monarch 11 Statics vs. -

3 Fischer Vs. Bent Larsen

Copyright © 2020 by John Donaldson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Donaldson, John (William John), 1958- author. Title: Bobby Fischer and his world / by John Donaldson. Description: First Edition. | Los Angeles : Siles Press, 2020. Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020031501 ISBN 9781890085193 (Trade Paperback) ISBN 9781890085544 (eBook) Subjects: LCSH: Fischer, Bobby, 1943-2008. | Chess players--United States--Biography. | Chess players--Anecdotes. | Chess--Collections of games. | Chess--Middle games. | Chess--Anecdotes. | Chess--History. Classification: LCC GV1439.F5 D66 2020 | DDC 794.1092 [B]--dc23 Cover Design and Artwork by Wade Lageose a division of Silman-James Press, Inc. www.silmanjamespress.com [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgments xv Introduction xvii A Note to the Reader xx Part One – Beginner to U.S. Junior Champion 1 1. Growing Up in Brooklyn 3 2. First Tournaments 10 U.S. Amateur Championship (1955) 10 U.S. Junior Open (1955) 13 3. Ron Gross, The Man Who Knew Bobby Fischer 33 4. Correspondence Player 43 5. Cache of Gems (The Targ Donation) 47 6. “The year 1956 turned out to be a big one for me in chess.” 51 7. “Let’s schusse!” 57 8. “Bobby Fischer rang my doorbell.” 71 9. 1956 Tournaments 81 U.S. Amateur Championship (1956) 81 U.S. Junior (1956) 87 U.S Open (1956) 88 Third Lessing J. -

Vassilis Aristotelous CYPRUS CHESS CHAMPION - FIDE INSTRUCTOR - FIDE ARBITER VASSILIS ARISTOTELOUS CHESS LESSONS © 2014 3 CONTENTS

CHESS TWO - BEYOND THE BASICS OF THE ROYAL GAME Vassilis Aristotelous CYPRUS CHESS CHAMPION - FIDE INSTRUCTOR - FIDE ARBITER VASSILIS ARISTOTELOUS CHESS LESSONS © 2014 3 CONTENTS Preface .............................................................................................................. 11 Chess Symbols ................................................................................................... 12 Introduction - The Benefits of Chess ................................................................ 15 Inspiring Tal ....................................................................................................... 19 Tactics Win Games ............................................................................................ 47 Tactical Exercises .............................................................................................. 49 Solutions to the Tactical Exercises..................................................................... 66 Great Sacrifices ................................................................................................. 77 Romantic Chess ............................................................................................... 102 ECO Chess Opening Codes ............................................................................ 116 Main Chess Openings ...................................................................................... 139 How to Analyse a Position............................................................................... 202 Chess Olympiads ............................................................................................ -

Monster Your Endgame Planning

Efstratios Grivas MONSTER YOUR ENDGAME PLANNING VOLUME 1 Chess Evolution Cover designer Piotr Pielach Monster drawing by Ingram Image Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2019 by Chess Evolution Monster your endgame planning. Volume 1 Copyright © 2019 Chess Evolution All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 978-615-5793-15-8 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Chess Evolution 2040 Budaors, Nyar utca 16, Magyarorszag e-mail: [email protected] website: www.chess-evolution.com Printed in Hungary TABLE OF CONTENTS Key to symbols ...............................................................................................................5 Foreword .........................................................................................................................7 Th e Endgame .................................................................................................................11 Th e Golden Rules of the Endgame ...........................................................................15 Evaluation — Plan — Execution ............................................................................... 17 CHAPTER 1. PAWN ENDINGS Pawn Power .................................................................................................................. 21 CHAPTER 2. MINOR PIECE