Japanese Art Japanese Art ENDURING UNDERSTANDING ESSENTIAL KNOWLEDGE Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

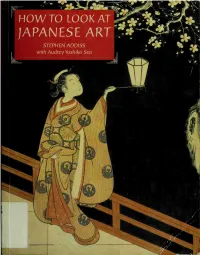

How to Look at Japanese Art I

HOWTO LOOKAT lAPANESE ART STEPHEN ADDISS with Audrey Yos hi ko Seo lu mgBf 1 mi 1 Aim [ t ^ ' . .. J ' " " n* HOW TO LOOK AT JAPANESE ART I Stephen Addi'ss H with a chapter on gardens by H Audrey Yoshiko Seo Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers ALLSTON BRANCH LIBRARY , To Joseph Seuhert Moore Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Addiss, Stephen, 1935- How to look at Japanese art / Stephen Addiss with a chapter on Carnes gardens by Audrey Yoshiko Seo. Lee p. cm. “Ceramics, sculpture and traditional Buddhist art, secular and Zen painting, calligraphy, woodblock prints, gardens.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8109-2640-7 (pbk.) 1. Art, Japanese. I. Seo, Audrey Yoshiko. II. Title N7350.A375 1996 709' .52— dc20 95-21879 Front cover: Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770), Girl Viewing Plum Blossoms at Night (see hgure 50) Back cover, from left to right, above: Ko-kutani Platter, 17th cen- tury (see hgure 7); Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875), Sencha Teapot (see hgure 46); Fudo Myoo, c. 839 (see hgure 18). Below: Ryo-gin- tei (Dragon Song Garden), Kyoto, 1964 (see hgure 63). Back- ground: Page of calligraphy from the Ishiyama-gire early 12th century (see hgure 38) On the title page: Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858), Yokkaichi (see hgure 55) Text copyright © 1996 Stephen Addiss Gardens text copyright © 1996 Audrey Yoshiko Seo Illustrations copyright © 1996 Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Published in 1996 by Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, New York All rights reserv'ed. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher Printed and bound in Japan CONTENTS Acknowledgments 6 Introduction 7 Outline of Japanese Historical Periods 12 Pronunciation Guide 13 1. -

The Deer Scroll by Kōetsu and Sōtatsu

The Deer Scroll by Kōetsu and Sōtatsu Reappraised Golden Week Lecture Series— Four Masterpieces of Japanese Painting: A Symposium Miyeko Murase, Former Consultant for Japanese Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Takeo and Itsuko Atsumi Professor Emerita, Columbia University Poem Scroll with Deer (part), Hon’ami Kōestu and Tawaraya Sōtatsu, early 17th century, handscroll, ink, gold and silver on paper, 13 3/8 x 372 in., Gift of Mrs. E. Frederick, 51.127 It has been quite some years since I last spoke here at this museum, so many in fact that I have lost count. It is really wonderful to be back, and I want to thank director Mimi Gates and curator Yukiko Shirahara, who invited me to speak today on the world-famous Deer Scroll by Sōtatsu and Kōetsu. This proud possession of the Seattle Art Museum is one of the most beautiful paintings ever created by Japanese artists.1 The scroll just came back from Japan after extensive restorative work. Although the handscroll itself does not bear any title, it is generally known as the Deer Scroll because the entire scroll is filled with images of deer, which are shown either singly, in couples, or in large herds. The animals are painted only in gold and/or silver ink, as is the very simple setting of sky, mist, and ground. As you may have noticed, these beautiful pictures of deer are really a background for the equally exquisite writings of waka poems in black ink. Here we have a symphony of three arts - poetry, painting, and calligraphy - as a testimonial to the ancient credo of Asia that these three arts occupy an equally important place in life and culture. -

Chinese and Japanese Literati Painting: Analysis and Contrasts in Japanese Bunjinga Paintings

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 Chinese and Japanese Literati Painting: Analysis and Contrasts in Japanese Bunjinga Paintings Qun Dai Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dai, Qun, "Chinese and Japanese Literati Painting: Analysis and Contrasts in Japanese Bunjinga Paintings" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 234. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/234 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chinese and Japanese Literati Painting: Analysis and Contrasts in Japanese Bunjinga Paintings Senior Project Submitted to The Division of the Arts of Bard College by Qun Dai Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2016 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to Professor Patricia Karetzky, my research supervisor, for her valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of this research work. I, as well, would like to offer my special thanks for her patient guidance, extraordinary support and useful critiques in this thesis process. -

Edo Avant Garde Introducing the Edo Era: Why Did Japanese Artists Create So Much Innovative Art? Part I

Edo Avant Garde Introducing the Edo era: Why did Japanese artists create so much innovative art? Part I CLASSROOM CONNECTIONS ELEMENTARY LESSON 1 In this lesson, students will explore the concept of creativity through an investigation of the development of new artistic techniques in a variety of works from the Edo period. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS: ● What is creativity and what factors may impact its development? ● How might religious beliefs/worldviews impact the creation of art? ● How does one paint using tarashikomi and mokkotsu, two techniques that we see used in Japanese paintings of the Edo period? ACTIVITIES: 1. Explore the concept of “creativity” by asking students what is meant by this term and by describing the factors that impact its development. ● Ask students to provide examples of the ways in which they express their own creativity. ● How might current events and/or life experience impact creativity? Provide several examples. ● How does science impact creativity? How has our knowledge of items such as plants and animals grown since the development of the microscope and x-rays? 2. Investigate the idea that one must know something about an object in order to be able to work with it. How much does one need to know in order to write or draw or paint something? ● Explore the concept of textures in nature through a hands-on investigation. Provide several examples of plants, flowers, rocks, bark, and leaves for students to first examine visually, then through touch, and finally through the creation of texture rubbings made by placing the objects under a sheet of paper and coloring over the top of the paper with crayons. -

Jprivilegiilllg Tt1bie- Vis1ulal: Jpartjiji

6 OBOEGAKI Volume 3 Number 2 JPrivilegiilllg tt1bie- Vis1Ulal: JPartJIJI @ Melinda Takeuchi Stanford University What follows is a revisedsyllabus from my one-quartercourse "Arts of War andPeace: Late Medieval and Early Modem Japan, 1500-1868." Like all syllabi, no matter how frequently I re-do it, this one seems never to reflect my current thinking about the subject. I find that as my approach moves farther from the way I was trained, which consisted mainly of stylistic analysis and aesthetic concerns, I have begun to wonder whether I am using art to illustrate culture or culture to illuminate art. Perhaps the distinction is no longer important. Next time I do the class I will approach the material more thematically ("The Construction of Gender," "The City," "Travel," etc.); I will also do more with the so-called minor or decorative arts, including robes, arms, armor, and ceramics. Text used was Noma Seirok~, Arts of Japan, vol. 2, Late Medieval to Modem (Tokyo, New York, and San Francisco: Kodansh;l International Ltd., 1980), chosen primarily for its reproductions. I also made a duplicate slide set of roughly 150 slides and put them on Reserve. POWER SPACES:MILITARY ARCHITECTURE OF THE LATE SIXTEENTH AND EARL Y SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES Various kinds of domestic architecture existed during the late sixteenth century (best viewed in screens known as Rakuchu Rakugai zu ~1fJ~..)i.~ depicting the city of Kyoto). The most common (and the least studied) are the long shingle-roofed rowhouses of commoners, which fronted the streets and often doubled as shop space. In contrast, wealthy courtiers and warriors lived in spacious mansions consisting of various buildings linked by roofed corridors and enclosed by wooden walls and sliding doors, the top half of which waS often papered with translucent shoji ~-=f screens. -

ART HISTORY RESEARCH PAPER an INVESTIGATION of JAPANESE AESTHETIC LIFE THROUGH the WORK of SOTATSU and KORIN Submitted by Scott

ART HISTORY RESEARCH PAPER AN INVESTIGATION OF JAPANESE AESTHETIC LIFE THROUGH THE WORK OF SOTATSU AND KORIN Submitted by Scott Bailey Art Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 1997 ABSTRACT OF THESIS AN INVESTIGATION OF JAPANESE AESTHETIC LIFE THROUGH THE WORK OF SQTATSU AND KORIN Obtaining an understanding of the main components of the Japanese insight into beauty requires not only a grasp of the formal visual elements of the style, but also an understanding of the aesthetic as it pervaded every aspect of life in Japan. Much has been written about the intimate relationship between crafts such as pottery and spiritual life under the influence of Zen, but in screens we have examples of a Japanese art form which blend characteristics of the flat, painted image with those of objects of utility. During the Momoyama and Edo eras of the 17th and 18th centuries came new advances in the Japanese style of painting, primarily due to the artists Sotatsu and Korin, now referred to as "The Great Decorators. 0 This paper traces the traditional Japanese aesthetic from its Eastern religious and philosophical background to its expression in the screen paintings of the Sotatsu-Korin School Connections to the activities of the Japanese way of life of the period and the specific vocabulary used to discuss art of all varieties in Japan help to illuminate key concepts such as irregularity, simplicity, intuition, decoration, pattern, and utility. All of these are intimately related to the Buddhist and Zen procedures for living an artful and natural life and all seek to provide a harmonious blend between the artificial and the natural. -

The Rimpa School and Autumn Colors in Japanese

Artists’ Biographies Special Exhibition: Celebrating the Rimpa School̓s 400th Anniversary TAKEUCHI Seihō TANAKA Hōji The Rimpa School and Autumn Colors in Japanese Art 1864-1942 1812-1885 Period: 1 September (Tue.) – 25 October (Sun.) 2015 (Closed on 9/24, 10/13 and on Mondays, except for 9/21 and 10/12) Hours: 10 am – 5 pm (Last admission at 4:30 pm) Born in Kyoto; given name was Tsunekichi. Studied with Born in Edo; at thirteen, became Sakai Hōitsu’s pupil at Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, Suzuki Kiitsu, (No. 25) is not displayed. Kōno Bairei. Initially used the art name 棲鳳 (Seihō). After the very end of Hōitsu’s life. In the Meiji period, exhib- No. 36 is a mural on permanent display in the museum entrance lobby on the 1st fl oor. traveling to Europe, replaced the fi rst character of his name ited works in the Competitive Show for the Promotion of with 栖, a homophone of the original character but includ- National Painting and the Vienna International Exposition | | ing the Chinese character element for “west” (西). Worked (1873). Particularly in his bird-and-fl ower paintings, he Foreword to modernize Nihonga and was a driving force in the Kyoto faithfully continued Hōitsu’s style, communicatinge his es- In 2015, we celebrate the four-hundredth anniversary of the launch of an art colony north of Kyoto in Takagamine by Hon’ami art world. Appointed an Imperial Household Artist in 1913 sential honesty. Kōetsu, the founding father of the Rimpa school. To commemorate that signifi cant event inRimpa history, the Yamatane Museum and awarded the Order of Culture in 1937. -

Byōbu the Grandeur of Japanese Screens

Byōbu The Grandeur of YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY Japanese Screens The material culture of a society can tell us much about its creators and the environment in which it developed. Japanese folding screens, or byōbu (literally “wind screens”), are a prime example. Free-standing, portable, and ornamented with calligraphy or pictorial images, byōbu commonly appear in pairs, each screen consisting of two, four, six, or eight panels. In addition to providing protection from wind, folding screens serve as attractive room dividers, enclosing and demarcating private spaces in the open interiors of Japanese palaces, temples, shrines, and elite homes. A prototype for byōbu, in the form of leather cords reinforced with zenigata, or use, the washi hinges allow the presentation the seventeenth century, where they were or inscribed panels were protected from light styles of Japanese painting. Selected from the separate panels with silk borders, came “coin-shaped” wooden washers.1 In the four- of a continuous image (fig. 1). Prior to this known as biombo.3 and dust. Their compact nature allowed for collection of the Yale University Art Gallery to Japan from Korea in 686 c.e. By the teenth century, the Japanese began using invention, each screen panel was surrounded Architecture played a large role in easy and tidy storage with an elegance of and supplemented by generous loans from the mid-eighth century, one hundred screens— hinges made of paper (kami chōtsugi), and by a silk border, which broke up the com- the development and use of byōbu. Early design in harmony with Japanese aesthetics. collections of Gallery supporters, the objects sixty-five of which included fabric designs this element distinguishes Japanese byōbu position. -

THE TALE of GENJI a Japanese Classic Illuminated the TALE of GENJI a Japanese Classic Illuminated

THE TALE OF GENJI a japanese classic illuminated THE TALE OF GENJI a japanese classic illuminated With its vivid descriptions of courtly society, gar- dens, and architecture in early eleventh-century Japan, The Tale of Genji—recognized as the world’s first novel—has captivated audiences around the globe and inspired artistic traditions for one thou- sand years. Its female author, Murasaki Shikibu, was a diarist, a renowned poet, and, as a tutor to the young empress, the ultimate palace insider; her monumental work of fiction offers entry into an elaborate, mysterious world of court romance, political intrigue, elite customs, and religious life. This handsomely designed and illustrated book explores the outstanding art associated with Genji through in-depth essays and discussions of more than one hundred works. The Tale of Genji has influenced all forms of Japanese artistic expression, from intimately scaled albums to boldly designed hanging scrolls and screen paintings, lacquer boxes, incense burners, games, palanquins for transporting young brides to their new homes, and even contemporary manga. The authors, both art historians and Genji scholars, discuss the tale’s transmission and reception over the centuries; illuminate its place within the history of Japanese literature and calligraphy; highlight its key episodes and characters; and explore its wide-ranging influence on Japanese culture, design, and aesthetics into the modern era. 368 pages; 304 color illustrations; bibliography; index THE TALE OF GENJI THE TALE OF GENJI a japanese classic illuminated John T. Carpenter and Melissa McCormick with Monika Bincsik and Kyoko Kinoshita Preface by Sano Midori THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London This catalogue is published in conjunction with “The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Jacket: Tosa Mitsuyoshi, “Butterflies”Kochō ( ), Chapter 24 of The Tale of Genji, late Illuminated,” on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from March 5 16th–early 17th century (detail, cat. -

Brushstrokes: Styles and Techniques of Chinese Painting Introduction

Brushstrokes STYLES AND TECHNIQUES OF CHINESE PAINTING This packet was originally produced for a November 1995 educator’s workshop Education Department Asian Art Museum - Chong Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture Prepared by: Molly Schardt, School Program Coordinator Edited by: Richard Mellott, Curator, Education Department So Kam Ng, Associate Curator of Education This teacher workshop and teacher resource packet were made possible by grants from The Soong Ching Ling Foundation, USA Asian Art Museum Brushstrokes: Styles and Techniques of Chinese Painting Introduction Brushwork is the essential characteristic of Chinese painting. Ink and brushwork provide the founda- tion of Chinese pictures, even when color is also used. Connoisseurs of Chinese art first notice the character of the line when they view a painting. In the quality of the brushwork the artist captures qiyun, the spirit resonance, the raison d'etre of a painting. Chinese Calligraphy and Writing In China, painting and writing developed hand in hand, sharing the same tools and techniques. Some sort of pliant brush, capable of creating rhythmically swelling and diminishing lines, appears to have been invented by the Neolithic period (ca. 4500-2200 B.C.E.) where it was used to decorate pottery jars with sweeping linear patterns. By the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-C.E. 220), both wall paintings and writing on strips of bamboo laced together to form books exhibit proficiency and expressiveness with the extraordinarily resilient Chinese brush and ink. Chinese writing is composed of block-like symbols which stand for ideas. Sometimes called “ideo- grams,” the symbols more often are referred to as “characters.” These characters, which evolved from pictograms (simplified images of the objects they represent), were modified over time to represent more abstract concepts. -

Japan Workshop V

The Arts of Edo Japan A Teacher Workshop on March 18, 2000 Asian Art Museum education programs are made possible, in part, by a grant from the California Arts Council. Acknowledgments Workshop materials prepared by Deborah Clearwaters, Asian Art Museum; with contribu- tions by Christy Bartlett and Scott McDougall of the Urasenke Foundation of San Fran- cisco; Sherie Yazman, teacher at George Washington High School, SFUSD; Lisa Nguyen; Stephanie Kao; and U-gene Kim, San Francisco State University History Department Intern. Thanks to Asian Art Museum staff Doryun Chong, Thomas Christensen, Alina Collier, Brian Hogarth, Michael Knight, and Yoko Woodson for their comments and suggestions; and most of all to Jason Jose for design and graphics under a tight deadline. Thanks to our presenters at today’s workshop: Laura Allen, Melinda Takeuchi, Christy Bartlett, Scott McDougall, Sherie Yazman, and Docents Sally Kirby, Mabel Miyasaki, and Midori Scott. The slides are presented in roughly chronological order. Twenty Asian Art Museum object photos by Kazuhiro Tsuruta unless indicated otherwise. Asian Art Museum Education Department A Map of Japan R Amur Khabarovsk Sakhalin Island CHINA Q Yuzhno Sakhalinsk Harbin Jixi C hung Jilin Hokkaido Vladivostok Liaoyuan F Sea NORTH KOREA F Cheng of dong Japan Pyongyang Seoul Incheon SOUTH KOREA JAPAN Honshu Taejeon Edo (Tokyo) Y Sea Sekigahara Taegu Mt. Fuji Nagoya Kyoto Pusan Himeji Kamakuka Hagi Nara Shizuoka Osaka Shikoku Nagasaki Kyushu E China Sea Pacific Ocean Asian Art Museum Education Department Introduction This workshop focuses on the Edo period (1615–1868) in Japan, and its rich artistic and cultural heritage. Teachers may chose to combine the slides and activities in this packet, which focus on courtly and literati arts, with other packets produced by the Asian Art Museum and other institutions treating this period that are listed in the Bibliography.