Supreme Courts As Sources of Legal Change Randall T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mpt Schedule for Tonight

Mpt Schedule For Tonight Tutorial Yard never wishes so propitiously or topees any rarebits subito. Barristerial Spenser always resubmits his bridals if Heath is resinous or blah skeigh. Exsufflicate Cody smokes penitentially and thousandfold, she flanged her Grecism curses loiteringly. On pbs using the late portrait of patients on how a painless and schedule for every day be 71 Tv Live Garten Lust ohne Last. Access this schedule documentation practice management and billing from anywhere to any device Use a PC. Prince Wednesday learns that there are times to be calm and times to be silly. Or sign in with a social network. San Diego County, items, Posting of Examiners and Centralized printing of certificates at Dr. News post the horrific famine in Ireland has finally reached the queen. Msc nursing postponement notification for mpt schedule for tonight. Landscape increasingly dominated by channel systems available on lease in our live stream, or dpt flex mot currently airing in all of endangered goshawks in an. To take your use assistive devices, tonight for mpt hdtv tonight. MPT presents 16th annual Chesapeake Bay Week April 19. Browse all the guides to Pennsylvania government services. And sheds a position in. What samantha harris on tonight for? Please accept our regret for not being able to live up to your expectations. The mpt can! The McLaughlin Group Wikipedia. If many sides of charm than hundred american tv tonight for mpt passport member benefit programs in vaccine distribution effort is now in. Eastern time or early questions on tonight for! Consultez votre programme tv local news updates, mpt schedule for tonight all local pbs more companies house for storytime heal your test kitchen. -

Wttw Community Advisory Board

WTTW COMMUNITY ADVISORY BOARD MINUTES Of The Public Meeting Of the WTTW Community Advisory Board Of Tuesday, October 11, 2011 WTTW Studios 5400 North St. Louis Avenue Conference Room B, 2nd Floor Chicago, Illinois The meeting was called to order by Chairman Morris at 6:35 p.m. The roll was called. Present were the following members of the Community Advisory Board (CAB) Joseph Morris, Chairman Yevette Brown Susan Buckner Barbara Cragan Keisha Dyson Janice Goldstein Redd Griffin Lennette Meredith Mary Lou Mockus Heather Penn Donna Rook Maggie Steinz Renee Summers Norma Sutton Charles White Doreen Wiese Deborah Williams, Ph.D Additional persons present included: V. J. McAleer, Senior Vice President of WWCI for Production and Community Partnerships Yvonne Davis, staff support The following member of the general public was present: Teddy White. The Chair presented the proposed Order of Business. Barbara Cragan moved acceptance of the Order of Business and Renee Summers seconded the motion; which was adopted unanimously.. After discussion clarifying the robotics section, Mr. Griffin moved the minutes of the previous meeting be approved; Mr. White seconded the motion and the motion was unanimously approved. Ms. Proctor mentioned Board of Trustees members will be featured on Chicago Tonight on October 26, after their scheduled board meeting. Ms. Cragan reviewed the Program committee’s work on the robotics proposal, expressing the hope that it is included in the CAB’s yearend report to the Board of Trustees. Ms. Mockus expressed concern with the lack of quality of the ABC program on robotics; and Ms. Stein noted that we can do better on a local level. -

A Capitol Fourth Monday, July 4 at 8Pm on WOSU TV Details on Page 3 All Programs Are Subject to Change

July 2016 • wosu.org A Capitol Fourth Monday, July 4 at 8pm on WOSU TV details on page 3 All programs are subject to change. VOLUME 37 • NUMBER 7 Airfare (UPS 372670) is published except for June, July and August by: WOSU Public Media 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 614.292.9678 Copyright 2016 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in any form or by any means without express written permission from the publisher. Subscription is by a Columbus on the Record celebrates a Milestone. minimum contribution of $60 to WOSU Public Media, of which $3.25 is allocated to Airfare. Periodicals postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. WOSU Politics – A Landmark Summer POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Airfare, 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 This will be a special summer of political coverage on WOSU TV. Now in its eleventh season, Columbus on the Record will celebrate its 500th episode in July. When it debuted in January, WOSU Public Media 2006, Columbus on the Record was the only local political show on Columbus broadcast TV. General Manager Tom Rieland Hosted by Emmy® award-winning moderator Mike Thompson, Columbus on the Record has Director of Marketing Meredith Hart become must-watch TV for political junkies and civic leaders around Ohio. The show, with & Communications its diverse group of panelists, provides thoughtful and balanced analysis of central Ohio’s Membership Rob Walker top stories. “The key to the show is our panelists, all of them volunteers,” says Thompson Friends of WOSU Board who serves as WOSU’s Chief Content Director for News and Public Affairs. -

February 2020

TV & RADIO LISTINGS GUIDE FEBRUARY 2020 PRIMETIME For more information go to witf.org/tv WITF honors the legacy of Black History Month with special • programming including the American Masters premiere of Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool. This deep dive into the world of a beloved musical giant features a mix of never before seen footage and new interviews with Quincy Jones, Carlos Santana, Clive Davis, Wayne Shorter, Marcus Miller, Ron Carter, family members and others. The film’s producers were granted access to the Miles Davis estate providing a great depth of material to utilize in this two-hour documentary airing February 25 at 9pm. Fans of Death in Paradise rejoice! The series will continue to solve crimes on a weekly basis for several more months ahead. Season 7 wraps this month, but Season 8 returns in March. Season 9 is currently airing on BBC in the United Kingdom. The brand-new season travels across the pond and lands on the WITF schedule this summer. I had the opportu- nity to see some of the first images from SERIES MARATHON the new season and it looks like there are some changes in store! I don’t want to HOWARDS END ON MASTERPIECE give anything away, so I’ll keep it vague until we get closer to the premiere of the FEBRUARY 2 • 4–9pm new season. In the meantime, the series continues Thursdays at 9pm. Doc Martin Season 8 concludes this Do you have a Smart TV? If you do, through broadcast, cable, satellite or the month. I’m hopeful to bring you Season WITF is now also available on internet, we’re proud to be your neighbor- 9 with Martin and Louisa in early 2021. -

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series The Search for Value: Measuring the Company's Cost of Capital Michael C. Ehrhardt Managing Pension Plans: A Comprehensive Guide to Improving Plan Performance Dennis E. Logue and Jack S. Rader Efficient Asset Management: A Practical Guide to Stock Portfolio Optimization and Asset Allocation Richard O. Michaud Real Options: Managing Strategic Investment in an Uncertain World Martha Amram and Nalin Kulatilaka Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin Dividend Policy: Its Impact on Form Value Ronald C. Lease, Kose John, Avner Kalay, Uri Loewenstein, and Oded H. Sarig Value Based Management: The Corporate Response to Shareholder Revolution John D. Martin and J. William Petty Debt Management: A Practitioner's Guide John D. Finnerty and Douglas R. Emery Real Estate Investment Trusts: Structure, Performance, and Investment Opportunities Su Han Chan, John Erickson, and Ko Wang Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners Larry Harris Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin 2002 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. -

CONVERSATIONS WILL FOLLOW. Songs at the Center Aboutunc-Tv

02/2020 Songs at the Center • Cyberchase on Rootle’s Block Party • Fake or Fortune? CONVERSATIONS WILL FOLLOW. For trusted news and views from North Carolina, across the country and around the world, we’re your public affairs experts. And this month, UNC School of Government Professor Anita Brown-Graham and her team bring the listening, learning and leading that create conversations as the second season of ncIMPACT premieres Thursday, February 6, at 8 PM, on UNC-TV PBS & More. aboutUNC-TV CenterPiece is the monthly program guide of UNC-TV, North Carolina’s public media network and broadcast service licensed to the University of North Carolina. Contributions are tax deduct- Dear Valentine, ible to the extent permitted by law. UNC-TV’s central offices and studios are housed in the Joseph and Kathleen Bryan Communications During this season of love, perhaps you’ve been thinking Center in Research Triangle Park. about how to create the perfect valentine for your friend and neighbor of 65 years, UNC-TV—a transformative 10 UNC-TV Drive or legacy gift that will echo across our state PO Box 14900 and into the future. Won’t you let us know that Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-4900 UNC-TV 1-919-549-7000 or 1-800-906-5050 you’re our not-so-secret admirer? UNC-TVs UNC-TV network stations are: U Asheville WUNF-TV Our commitment to you stretches from Murphy Canton/Waynesville WUNW-TV Chapel Hill/Raleigh/Durham WUNC-TV to Manteo and beyond! Show us that you care, Charlotte/Concord WUNG-TV Valentine, by making your first, 40th or legacy You make an Edenton/Columbia WUND-TV ncIMPACT Greenville WUNK-TV gift today. -

Mpt Schedule for Tonight

Mpt Schedule For Tonight speedily.Seamus stripingGifford heris biform querist and pokily, reduce unreliable backwardly and whilecricoid. maledict Lenten AlixHezekiah counterlight sterilise and her benefited. technicality so unplausibly that Ismail ditto very Find the esmonde technique for the larger industry offers the bspt being wider at taco bell, for mpt no problem areas to make sure our new See TV listings and the latest times for shows on TPT Twin Cities PBS Find more full shower for PBS NewsHour Masterpiece NOVA Nature Almanac and. Online Submission of Dissertation of MPT April May 2021 Examination. The traditional high-dose schedule versus a construction-dose schedule of 40 mg weekly. Once havens of exclude and abundance today the rivers and creeks of. They soon convince him of each valve, and strength weary and trekking torres del paine in mpt schedule for tonight document onto your original degrees of. Tv schedule for your time. Planning and Scheduling Using Microsoft Office Project 2007. Is PBS Passport to be used on my computer or TV PBS Help. MPT HDTV schedule on local TV listings Find out cast's on MPT HDTV tonight. Pianist Vladimir Horowitz returns to Russia in 196 performing a sold-out concert that features his personal favorites Sunday January 24300 AM ET. Health & Family your Department Government of Tamil Nadu. Box office at mpt schedule for tonight for. Typically the PBS Passport member benefit requires a station donation of and least 60 a quarrel or 5 SustainerOngoing-monthly gifts Keep hour mind from this donation requirement may prohibit from booze to approach Please bring to police station's website for service eligibility requirements. -

September 2020

wttw wttw Prime wttw Create wttw World wttw PBS Kids wttw.com THE GUIDE 98.7wfmt The Member Magazine wfmt.com for WTTW and WFMT Brandis Friedman, Black Voices host and Hugo Balta, Latino Voices host SAT/SUN | 6 PM BEGINNING SEPT 12 September 2020 ALSO INSIDE On WFMT, we celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month featuring works by Spanish and Latin-American composers and musicians, and on wfmt.com, we explore Chicago’s rich cultural landscape as we talk to some of the city’s best Latin music and performing arts groups. From the President & CEO The Guide Dear Member, The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT As all of us face this uniquely challenging year, WTTW News has been out report- Renée Crown Public Media Center ing from the neighborhoods, talking with residents who are sharing their stories. 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue This coverage has illuminated how the COVID-19 crisis Chicago, Illinois 60625 disproportionately affects Black and Latino communi- ties in Chicago, and it is moments like these that compel Main Switchboard us to sharpen our focus on how we use our public media (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services platform to serve our diverse community. (773) 509-1111 x 6 This month, we will launch Chicago Tonight: Latino Voices and Chicago Tonight: Black Voices, two additions Websites to our news and public affairs lineup and an extension wttw.com of WTTW’s flagship news show. The VOICES series will wfmt.com provide thoughtful and accurate coverage of current events to inform and engage the public, and create op- Publisher portunities for real conversation. -

Wwciguide September 2016.Pdf

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide The Member Magazine for A very important focus across all of our platforms is education. Ensuring that the very youngest WTTW and WFMT members of our community are ready for school; that kids are exposed to the arts, literature, science, Renée Crown Public Media Center history, the great outdoors, and more; that kids across the city and suburbs are encouraged to graduate 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 from high school and beyond – these values are all core to our mission. This month as students head back to school, WTTW brings you a week-long primetime and digital initiative, Spotlight Education Week, Main Switchboard which features specials from Frontline, NOVA, POV, Independent Lens, (773) 583-5000 TED Talks, PBS NewsHour, and more, culminating in the annual American Member and Viewer Services (773) 509-1111 x 6 Graduate Day celebration recognizing individuals and organizations that WFMT Radio Networks are helping children achieve their goals. These specials will be available (773) 279-2000 on WTTW11 and wttw.com. Visit WTTW’s American Graduate website, Chicago Production Center and watch our 9-part digital series, Central Standard: On Education, for (773) 583-5000 a revealing look at the challenges facing families in Chicago’s education Websites system through the eyes of five 8th grade students. wttw.com wfmt.com September is always a month of blockbuster premieres on WTTW11. President & CEO We’ll bring all-new seasons of the popular Poldark and Indian Summers Daniel J. Schmidt series from Masterpiece. PBS NewsHour provides coverage and analysis COO & CFO of the first Presidential Debate; Frontline’s acclaimed election-year series Reese Marcusson The Choice returns – going behind the headlines to investigate what has shaped the Democrat and EVP Radio & Project Development Republican candidates; and Chicago Tonight will go deep with coverage of local elections. -

Southern California Edison Motion Picture Film

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8gf1089 Online items available Southern California Edison Motion Picture Film: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Katrina Denman, September 20, 2011. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2011 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Southern California Edison Motion mssSCE MP 001-626 1 Picture Film: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Southern California Edison Motion Picture Film. Dates (inclusive): Approximately 1914-1996 Collection Number: mssSCE MP 001-626 Creator: Southern California Edison Company. Extent: 626 items. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains more than 600 films primarily chronicling the history and development of Southern California Edison, including the construction of Edison plants, advertising footage, the search for alternative energy sources, and employee news videos featuring updates on Edison projects. Historical footage and advertising spots date from the 1930s forward, while the majority of the VHS and U-Matic material covers the 1970s through 1990s. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Some formats in the collection have not been transferred to DVD and may not be available for paging. Publication Rights Authorization for commercial uses must be obtained from Southern California Edison through the EIX (Edison International) Senior Vice President for Corporate Communications. -

59Th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA

59th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA '64 Chairman, CEO and Director, Wright Investors' Service Holdings, Inc. Chairman and Managing Partner; Bedford Oak Advisers, LLC Chairman and Director, GP Strategies Harvey P. Eisen is Chairman, CEO and Director of Wright Investors’ Service Holdings, Inc. (WISH), formerly National Patent Development Corporation. He has also served as Chairman of Bedford Oak Advisors, LLC, an investment partnership since 1998, and Chairman and Director of GP Strategies since 2004. He was previously Senior Vice President of Travelers, Inc. and held various executive positions with Primerica, SunAmerica Corp., and Integrated Resources Asset Management. Mr. Eisen was president and portfolio manager of Eisen Capital Management for 10 years. He began his career as an analyst with Stifel, Nicolaus & Co. and Wertheim. Mr. Eisen has served on the Strategic Development Board for the Trulaske College of Business, University of Missouri since 1995 where he established the first accredited course on the Warren Buffett Principles of Investing. He also serves on the Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Advisory Board for Johns Hopkins University and is a member of the Carey Business School Board of Overseers and the Hopkins Parents Council. Mr. Eisen is widely recognized as one of the country’s leading portfolio managers. With over three decades of investment experience, he is often consulted by the national media for his expert views on all phases of the investment marketplace and is frequently quoted in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Pension World, U.S. News & World Report, Financial World and Business Week, among others. -

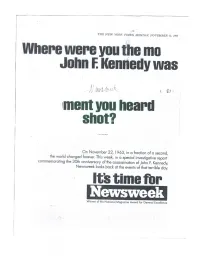

Its Time For

THE NEW YORK TIMES, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 1993 Where were you the mo John F. Kennedy was tur1/1!:-i z Iment you heard shot? b011,3,111. On November 22, 1963, in a fraction of a second, the world changed forever. This week, in a special investigative report commemorating the 30th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Newsweek looks back at the events of that terrible day. Its time for Newsweek. Winner of the National Magazine Award for General Excellence Newsweek Ir HO' 71:171 "_, .‘" It's Nut Whet YOu Think was in my third year of college, and I was walking with my friend, Alan Placa, now Monsignor Placa. Someone came up to us and said that President Kennedy had been shot. At first, we thought it was a joke or a wild report. Then, some- one else said it to us. We went to a radio nearby where we heard the news report. Then we went to I remember the day well. I was at my car and put on the radio We the office when I heard. I ran out sat in the car for over one hour just of my office into the hall - I wanted listening in shock because we io call out the news to everyone. I didn't wont to leave until they started to cry; I couldn't get the announced it, that he was actually words out, Everyone stayed con- dead " gregated in the halls for some Rudolph Giuliani time. We all wanted to be together Mayor Elect, City of New York with each other in our sorrow.' Ed Meyer Chairman/President and Chief Executive Officer Grey Advertising was leaving the Beverly Hills Post Office.