American Idol: Should It Be a Singing Contest Or a Popularity Contest?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This Copy of the Thesis Has Been

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2012 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman Vita-More, Natasha http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1182 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 1 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman by NATASHA VITA-MORE A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts April 2012 2 Natasha Vita-More Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman The thesis’ study of life expansion proposes a framework for artistic, design-based approaches concerned with prolonging human life and sustaining personal identity. To delineate the topic: life expansion means increasing the length of time a person is alive and diversifying the matter in which a person exists. -

Alumni Profiles from Around the World

Volume 34, Number 1 Spring 2011 ALUMNI PROFILES FROM AROUND THE WORLD INSIDE: A conversation with Steve Case | Fifty years of Business Night Entrepreneurs compete for the top prize at The 2011 UH Business Plan Competition DEAN’S MESSAGE ALOHA, Welcome to the Spring 2011 issue of Kong venture capitalist Danny Lui and encourage you to become a part of this Shidler Business. It has been an action- philanthropist Bernard Osher. great group of business professionals and packed semester and we are very proud to Our alumni continue to be one of our learn more about the countless projects share all of our accomplishments with you greatest assets. Their contributions of time, that this organization has coordinated in the following pages. resources and knowledge have played a benefiting alumni, students and the business Most recently, the College received re- major role in the success of our students and community. accreditation from AACSB International, programs. For instance, this May countless It is truly a fun time to be a part of the the world’s leading accrediting institution alums volunteered to mentor students at Shidler ‘ohana. Thanks for sharing in our for business schools. This is the standard by Business Night’s 50th Anniversary event. success. As always, please keep in touch as which all business schools strive for and we In this issue, we explore the history of we welcome your comments and feedback. thank all of our stakeholders for helping us this popular gathering and the impact it to reach our goals. has had on students’ careers through the Sincerely, We hosted several fascinating guest decades. -

KANG-THESIS.Pdf (614.4Kb)

Copyright by Jennifer Minsoo Kang 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jennifer Minsoo Kang Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar Karin G. Wilkins From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 by Jennifer Minsoo Kang, B.A.; M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication To my family; my parents, sister and brother Abstract From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 Jennifer Minsoo Kang, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar The format program trade has grown rapidly in the past decade and has become an important part of the global television market. This study aimed to give an understanding of this phenomenon by examining how global formats enter and become incorporated into the national media market through a case study analysis on the Korean format market. Analyses were done to see how the historical background influenced the imported format flows, how the format flows changed after the media liberalization period, and how the format uses changed from illegal copying to partial formats to whole licensed formats. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the global format program flows are different from the whole ‘canned’ program flows because of the adaptation processes, which is a form of hybridity, the formats go through. -

KARELIA UNIVERSITY of APPLIED SCIENCES Degree Program in International Business

KARELIA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Degree Program in International Business Thi Phuong Anh Dinh VIETNAM AS A POTENTIAL MARKET FOR COMPANY A- A VOCAL INSTITUTE FROM DENMARK Thesis August 2018 2 THESIS August 2018 Degree Program in International Business Tikkarinne 9 80220 JOENSUU FINLAND Tel. +35813 260 600 Author(s) DINH, THI PHUONG ANH Title VIETNAM AS A POTENTIAL MARKET FOR COMPANY A- A VOCAL INSTITUTE FROM DENMARK Commissioned by Case Company A Abstract This research aims to discover if Vietnam would be a potential market for the three-year course of Company A, by answering three research questions on market situations, market demands, and export strategy. The research first provides the firm with an overall picture of the Vietnamese music education market through secondary data, which is extracted from trustworthy and scholarly sources. The author then analyzes primary data obtained from interview-based qualitative research with an attempt to offer insight into customers’ demands on the three-year course. Recommendations are given regarding possible future actions for Company A, along with an export strategy proposal. As a result, the information from the research assists the case company with decisions related to market entry engagement in Vietnam. Language Pages 50 English Appendices 4 Pages of Appendices 4 Keywords Market research, Vietnamese Market, Education Export, Export Strategy 3 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Case -

C NTENTASIA #Thejobsspace Pages 14, 15, 16

Bumper jobs issue C NTENTASIA #TheJobsSpace pages 14, 15, 16 www.contentasia.tv l https://www.facebook.com/contentasia?fref=ts facebook.com/contentasia l @contentasia l www.asiacontentwatch.com New Warner TV debuts on 15 March iZombie leads launch schedule Turner unveils the new version of regional entertainment channel Warner TV on 15 March, three days ahead of the express premiere in Asia of iZombie, the brain-eat- ing zombie show inspired by DC Comics. The new Warner TV debuts with a re- worked logo and the tagline “Get Into It”. The new schedule is divided into three clear pillars – drama, action and comedy. More on page 3 Hong Kong preps for Filmart 2015 800 exhibitors, 30 countries expected Digital entertainment companies are ex- pected to turn out in force for this year’s 19th annual Hong Kong Filmart, which runs from 23-26 March. Organisers said in the run up to the market that about 170 digital companies would participate. About 18% of these are from Hong Kong. The welcome mat is also being rolled More on page 16 Facing facts in China Docu bosses head for Asian Side of the Doc About 600 delegates are expected in the Chinese city of Xiamen for this year’s Asian Side of the Doc (ASD), including the event’s first delegation from Brazil and more indie producers than ever. This year’s event (17-20 March) takes place against sweeping changes in Chi- More on page 18 9-22 March 2015 page 1. C NTENTASIA 9-22 March 2015 Page 2. -

Number 40 - February 2012

The Babbler Number 40 - February 2012 Made in South Africa Consumed in Vietnam Photo: Jonathan C. Eames Number 40 - February 2012 CONTENTS Working together for birds and people • Comment 448 South African rhinos killed in 2011: A rhino lost every 20 BirdLife International in Indochina is a hours subregional programme of the BirdLife Secretariat operating in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and • Features The Future of the Mekong River Still Hangs in the Balance Vietnam. It currently has two offices in the region: Logging in the wild west Vietnam Programme Office • Regional News Cambodia opens controversial mega-dam Room 211-212, D1 building, Illegal South African rhino killings hit record high Van Phuc Diplomatic Compound; Brown and Northern Boobooks both occur in Thailand 298 Kim Ma street, Ba Dinh district, Hanoi, Vietnam Two new paper clip-sized frogs discovered in Vietnam P.O. Box 89 • Rarest of the rare Hoan Kiem softshell turtle (Rafetus swinhoei) 6 Dinh Le, Hanoi, Vietnam Tel: +84-4-3 514 8904 • Project Updates CEPF- Regional Implementation Team updates Securing the future for Gurney’s Pitta and its forest habitat Cambodia Programme Office #9, Street 29 Tonle Basac, • Reviews Wild Mekong Chamkarmon, Phnom Penh, Cambodia • Publications Impacts of warming on lowland forests Historical and current status of vultures in Myanmar P.O.Box: 2686 Greater Adjutant Leptoptilos dubius Tel/Fax: +855 23 993 631 • Photo spot • From the archives World Press Photo of the Year 2011 winner www.birdlifeindochina.org The Babbler 40 - February 2012 Comment 448 South African rhinos killed in 2011: A rhino lost every 20 hours am recently returned from a study tour to South Africa: the objective of which was to help Cambodian government and private sector representatives appreciate the opportunity presented by high-end I safari tourism and assess whether Cambodia could use a similar approach to ensure the long term conservation of its biodiversity-rich areas (as its protected areas system is failing). -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

La Construcción Discursiva Del Espectador En Los Reality Shows. El Caso De Gran Hermano Del Pacífico

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS Y ARTES DE LA COMUNICACIÓN La construcción discursiva del espectador en los reality shows. El caso de Gran Hermano del Pacífico. Tesis para optar el Título de LICENCIADA EN PUBLICIDAD Presentada por CYNTHIA INGRID CABREJOS CALIENES Lima 2007 INTRODUCCIÓN El presente trabajo de investigación lleva como título: “La construcción discursiva del espectador en los reality shows. El caso de Gran Hermano del Pacífico”. Partiendo de las repercusiones sociales que este formato ha tenido en el plano social e individual, me interesa centrar mi análisis en esta nueva forma de hacer televisión que explota día a día la publicidad de la intimidad y el entretenimiento como recursos válidos para ganar audiencias. Todos sabemos que la televisión ejerce una fuerte influencia en sus televidentes, especialmente en la forma en la que estos se relacionan con su entorno. Sin duda, las imágenes de la televisión de hoy representan a su espectador, en la forma en que este concibe su sociedad y además, en cuáles son sus hábitos de consumo. Por otro lado, tenemos que la forma en la que estos reality shows presentan los objetos que exhiben y cuánto exhiben de ellos, es muestra de su papel por construir a un tipo de espectador ideal. Como un libro que ha sido escrito para un lector que idealmente interpreta y comprende los contenidos de la forma que lo ha concebido el autor, los reality shows establecen marcas enunciativas para atribuirle a su espectador diferentes competencias que finalmente terminen por fidelizarlo y engancharlo al drama. Precisamente la pregunta que esta investigación pretende responder es cómo el discurso de los realities (concentrándose particularmente en el de Gran Hermano) construye a un espectador ideal omnisciente y omnividente. -

Sprungbrett Oder Krise? Das Erlebnis Castingshow-Teilnahme

Sprungbrett oder Krise? 48 Maya Götz, Christine Bulla, Caroline Mendel Sprungbrett oder Krise? Das Erlebnis Castingshow-Teilnahme Landesanstalt für Medien Nordrhein-Westfalen (LfM) Zollhof 2 40221 Düsseldorf Postfach 103443 40025 Düsseldorf Telefon V 021 1/77007-0 Telefax V 021 1/72 71 70 E-Mail V [email protected] LfM-Dokumentation Internet V http://www.lfm-nrw.de ISBN 978-3-940929-28-0 Band 48 Sprungbrett oder Krise? Das Erlebnis Castingshow-Teilnahme Sprungbrett oder Krise? Das Erlebnis Castingshow-Teilnahme Eine Befragung von ehemaligen TeilnehmerInnen an Musik-Castingshows Maya Götz, Christine Bulla, Caroline Mendel Ein Kooperationsprojekt des Internationalen Zentralinstituts für das Jugend- und Bildungsfernsehen (IZI) und der Landesanstalt für Medien Nordrhein-Westfalen (LfM) Impressum Herausgeber: Landesanstalt für Medien Nordrhein-Westfalen (LfM) Zollhof 2, 40221 Düsseldorf www.lfm-nrw.de ISBN 978-3-940929-28-0 Bereich Kommunikation Verantwortlich: Dr. Peter Widlok Redaktion: Regina Großefeste Bereich Medienkompetenz und Bürgermedien Verantwortlich: Mechthild Appelhoff Redaktion: Dr. Meike Isenberg Titelbild: Collage © Wild GbR Lektorat: Viola Rohmann M. A. Gestaltung: disegno visuelle kommunikation, Wuppertal Druck: Börje Halm, Wuppertal April 2013, Auflage: 1.000 Exemplare Nichtkommerzielle Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung ist ausdrücklich erlaubt unter Angabe der Quelle Landesanstalt für Medien Nordrhein-Westfalen (LfM) und der Webseite www.lfm-nrw.de Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 8 Zusammenfassung 9 Einleitung 11 1 Das System Castingshow -

JOURNAL of MEDIA and INFORMATION WARFARE Centre for Media and Information Warfare Studies Volume 1 JUNE 2008 ISSN1985-563X

Mt\ Publication Cenire (L PI \ \ , UNIVERSITI <&Bb TEKNOLOGI ^^ MARA JOURNAL OF MEDIA AND INFORMATION WARFARE Centre For Media And Information Warfare Studies Volume 1 JUNE 2008 ISSN1985-563X Media Warfare: A Global Challenge in the 21 Century Rajib Gharri Strategic Communications and the Challenges Philip M. Taylor Of the Post 9/11 World The Impact of Mobile Dij W.Hutchinson on Influencing Behavior: Journalist in the Zone of Az.lena Khalid The need to Respect Intel umanitarian Law Outcome based education: A Computational Measurement Azrilah Abdul Aziz on Special Librarian Intelligence Competency Constructing War Accounts in Malaysia Che Mahz.an Ahmad Non-Violence Approach: The Challenge in Philippine Broadcasting Clarita Valdez - Ramos Global Media Versus Peace Journalism Faridah Ibrahim JOURNAL OF MEDIA AND INFORMATION WARFARE Center For Media And Information Warfare Studies EDITORIAL BOARD Journal Administrator Muhamad Azizul Osman Managing Editors Assoc. Prof. Mohd Rajib Ghani Muhamad Azizul Osman Language Editor Assoc. Prof Dr Saidatul Akmar Zainal Abidin Editorial Advisory Board (MALAYSIA) Assoc. Prof Mohd Rajib Ghani, Universiti Teknologi MARA Assoc. Prof Dr. Adnan Hashim, Universiti Teknologi MARA Assoc. Prof. Faridah Ibrahim, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Editorial Advisory Board (INTERNATIONAL) Prof. Phillip M. Taylor, University of Leeds and Distinguish Prof. UiTM W. Hutchinson, Edith Cowan University, Western Australia Clarita Valdez-Ramos, University of the Philippines Judith Siers-Poisson, Center for Media and Democracy, USA Copyright 2008 by Centre for Media and Information Warfare Studies, Faculty of Mass Communication and Media Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA, 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia All right reserved. No pan of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher. -

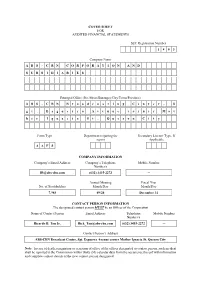

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If report Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number/s [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 7,985 09/24 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Ricardo B. Tan Jr. [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note: In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. -

TCPDF Example

Beat: Music A TWENTY-TWO YEAR OLD MAN FROM HANOVER BECAME THE LATEST WINNER OF VIETNAM IDOL TRONG HIEU WAS TRAVELLING FOR HOLIDAYS PARIS - HANOVER - HANOI, 04.08.2015, 10:45 Time USPA NEWS - TRONG HIEU coming from Hanover was planning only to spend holidays in country where his parents grew up. However, he was about to make a name for himself as South-East Asian country's favorite "hot boy from GERMANY". TRONG HIEU was born in GERMANY where his parents emigrated from VIETNAM in 1991. Before leaving for VIETNAM, a friend of his told him that over there where held auditions for VIETNAM IDOL. Convinced about the idea, TRONG HIEU applied and after passing all the auditions, he became very quickly a favorite in the competition earning a nickname and the adoration of thousands of fans. Inundated with support, TRONG HIEU rounded off his time on the show with a rendition of Mark Ronson's "Uptown Funk". He earned seventy-one per cent of the votes, storming to victory ahead of competitor BICH NGOC. He resumed his victory with the high-level of presomption that his German's background helped a lot, Asian people loving EUROPE very much. He added also that his vietnamese was far from being perfect and his image was attractive because bringing something different and foreigner as being also with vietnamese origins. His success made him popular and recognizable. He is often spotted in the street and people either wave at him or ask for photos. However, he doesn't plan to stay in VIETNAM, just to travel back and forth between the 2 Article online: https://www.uspa24.com/bericht-4729/a-twenty-two-year-old-man-from-hanover-became-the-latest-winner-of-vietnam-idol.html Editorial office and responsibility: V.i.S.d.P.