Appendix 1: Arthur Miller's Contribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

295 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-74538-3 - The Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller, Second Edition Edited by Christopher Bigsby Index More information INDEX Aarnes, William 281 Miller on 6, 152, 161 Abbott, Anthony S. 279 and No Villain/They Too Arise 6, 25, 28 “About Theatre Language” 76 productions xiii, 159, 161, 162 Ackroyd, Peter 166–67 revisions 160, 161 Actors’ Studio 220, 226 American Legion 215 Adding Machine, The 75 Anastasia, Albert 105 Adler, Thomas P. 84n, 280, 284 Anastasia, Tony 105, 108n Adorno, Theodor 201 Anderson, Maxwell 42 After the Fall xii, xiii, 4, 8, 38, 59–60, 61, Angel Face 209 118, 120–26, 133, 139, 178, 186, 262, Another Part of the Forest 285 265, 266 Anthony Adverse 216 changing critical reception 269–70 Antler, Joyce 290 The Last Yankee and 178 Archbishop’s Ceiling, The 5–6, 8, 141, Miller on 54–55, 121–22, 124, 126, 265 145–51, 167, 168 productions xii, xiii, 121, 123, 124–25, Miller on 147, 148, 152 156–57, 270, 283 productions xiii, 159, 161–62 The Ride Down Mount Morgan and 173 revisions 141, 159, 161, 162n structure 7, 128 Aristotle 13, 64, 234, 264 studies of 282, 284–85, 288, 290, 293 Aronson, Boris 129 viewed as autobiographical/concerned Art of the Novel, The 237n with Monroe 4, 121, 154, 157, 195, Arthur Miller Centre for American Studies 269, 275 (UEA) xiv, xv, 162 Ajax 13 Arthur Miller Theatre, University of Albee, Edward 154 Michigan xv Alexander, Jane 165 Aspects of the Novel 235 All My Sons xi, 2, 4, 36–37, 47, 51–62, 111, Asphalt Jungle, The 223 137, 209, 216, 240, 246, 265 Assistant, The 245 film versions xiv, 157–58, 206–12, 220, Atkinson, Brooks 293 232 Auden, W. -

Biblioteques De L'hospitalet

BIBLIOTECA TECLA SALA April 16, 2020 All My Sons Arthur Miller « The success of a play, especially one's first success, is somewhat like pushing against a door which suddenly opens from the other side. One may fall on one's face or not, but certainly a new room is opened that was always securely shut until then. For myself, the experience was invigorating. It made it possible to dream of daring more and risking more. The audience sat in silence before the unwinding of All My Sons and gasped when they should have, and I tasted that power which is reserved, I imagine, for Contents: playwrights, which is to know that by one's invention Introduction 1 a mass of strangers has been publicly transfixed. Author biography 2-3 Arthur Miller All My Sons - 4 Introduction & Context All My Sons - 5-6 » Themes Notes 7 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_My_Sons] Page 2 Author biography Arthur Miller is considered Street Crash of 1929, and had to Willy Loman, an aging Brooklyn one of the greatest American move from Manhattan to salesman whose career is in playwrights of the 20th Flatbush, Brooklyn. After decline and who finds the values century. His best-known plays graduating high school, Miller that he so doggedly pursued have include 'All My Sons,' 'The worked a few odd jobs to save become his undoing. Crucible' and the Pulitzer enough money to attend the Prize-winning 'Death of a University of Michigan. While in Salesman won Miller the highest Salesman.' college, he wrote for the student accolades in the theater world: paper and completed his first the Pulitzer Prize, the New York Who Was Arthur Miller? play, No Villain, for which he won Drama Critics' Circle Award and the school's Avery Hopwood the Tony for Best Play. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

Two Tendencies Beyond Realism in Arthur Miller's Dramatic Works

Inês Evangelista Marques 2º Ciclo de Estudos em Estudos Anglo-Americanos, variante de Literaturas e Culturas The Intimate and the Epic: Two Tendencies beyond Realism in Arthur Miller’s Dramatic Works A critical study of Death of a Salesman, A View from the Bridge, After the Fall and The American Clock 2013 Orientador: Professor Doutor Rui Carvalho Homem Coorientador: Professor Doutor Carlos Azevedo Classificação: Ciclo de estudos: Dissertação/relatório/Projeto/IPP: Versão definitiva 2 Abstract Almost 65 years after the successful Broadway run of Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller is still deemed one of the most consistent and influential playwrights of the American dramatic canon. Even if his later plays proved less popular than the early classics, Miller’s dramatic output has received regular critical attention, while his long and eventful life keeps arousing the biographers’ curiosity. However, most of the academic works on Miller’s dramatic texts are much too anchored on a thematic perspective: they study the plays as deconstructions of the American Dream, as a rebuke of McCarthyism or any kind of political persecution, as reflections on the concepts of collective guilt and denial in relation to traumatizing events, such as the Great Depression or the Holocaust. Especially within the Anglo-American critical tradition, Miller’s plays are rarely studied as dramatic objects whose performative nature implies a certain range of formal specificities. Neither are they seen as part of the 20th century dramatic and theatrical attempts to overcome the canons of Realism. In this dissertation, I intend, first of all, to frame Miller’s dramatic output within the American dramatic tradition. -

All My Sons As Precursor in Arthur Miller's Dramatic World

All My Sons as Precursor in Arthur Miller’s Dramatic World Masahiro OIKAWA※ Abstract Since its first production in 1947, Arthur Miller’s All My Sons has been performed and appreciated worldwide. In academic studies on Miller, it secures an important place as a precursor, because it has encompassed such themes as father-son conflict, pursuit of success dream in the form of a traditional tragedy as well as a family and a social play. As for techniques, to begin with, the Ibsenite method of dramatization of the present critical situation and presentation of the past “with sentimentality” are obvious. Secondly, the biblical tale of Cain and Abel from the Old Testament allows the play to disguise itself as a modern morality play on “brotherly love.” Thirdly, Oedipus’s murder of his father in Oedipus Rex is used symbolically to place the play in the Western tradition of drama. Taking all these major themes and techniques into account, the paper argues that the play is dramatizing the universal, and that by looking at the conflict between father and son, we can understand why Miller’s message in All My Sons is significant for Japanese andiences. I. Introducion Most of the reviews appearing in the major newspapers and magazines on All My Sons (1947) were rather favorable, which is quite understandable considering that the play vividly depicts the psychological aspects of the United States during and immediately after the Second World War in a realistic setting. In fact, it is impossible to understand the problems Joe and Chris Keller, the father and the son, get involved in without the background of the war. -

100 Years on the Road, 108 a Christmas Carol, 390 a Cool Million

Cambridge University Press 0521605539 - Arthur Miller: A Critical Study Christopher Bigsby Index More information INDEX 100 Years on the Road,108 Ann Arbor, 12 Anna Karenina,69 A Christmas Carol,390 Anti-Semitism, 13, 14, 66, 294, 330, A Cool Million,57 476, 485, 488 AMemoryofTwoMondays,6,129,172, Apocalypse Now,272 173, 200, 211 Arden, John, 157 A Nation of Salesmen,107 Arendt, Hannah, 267, 325 APeriodofGrace, 127 Arnold, Eve, 225 A Search for a Future,453 Aronson, Boris, 251 A Streetcar Named Desire, 98, 106, 145 Artaud, Antonin, 283 A View from the Bridge, 157, 173, 199, Arthur Miller Centre, 404 200, 202, 203, 206, 209, 211, 226, Auschwitz–Birkenau, 250, 325, 329, 351, 459 471 Abel, Lionel, 483 Awake and Sing, 13, 57, 76 Actors Studio, 212 Aymee,´ Marcel, 154, 156 Adorno, Theodore, 326 After the Fall, 5, 64, 126, 135, 166, 203, ‘Babi Yar’, 488 209, 226, 227, 228, 248, 249, 250, Barry, Phillip, 18 257, 260, 264, 267, 278, 280, 290, Barton, Bruce, 427 302, 308, 316, 322, 327, 329, 331, BBC, 32 332, 333, 334, 355, 374, 378, 382, Beckett, Samuel, 120, 175, 199, 200, 386, 406, 410, 413, 415, 478, 487, 488 204, 209, 250, 263, 267, 325, 328, Alger, Horatio Jr., 57, 113 329, 387, 388, 410, 475 All My Sons,1,13,17,42,47,64,76,77, Bel-Ami,394 98, 99, 132, 136, 137, 138, 140, 197, Belasco, David, 175 288, 351, 378, 382, 388, 421, 432, 488 Bell, Daniel, 483 Almeida Theatre, 404, 416 Bellow, Saul, 74, 236, 327, 372, 376, Almost Everybody Wins,357 436, 470, 471, 472, 473, 483 American Clock, The, 337 Belsen, 325 American Federation of Labour, 47 -

Arthur Miller's Contentious Dialogue with America

Louise Callinan Revered Abroad, Abused at Home: Arthur Miller’s contentious dialogue with America A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at St Patrick’s College, Dublin City University Supervisor: Auxiliary Supervisor: Dr Brenn a Clarke Dr Noreen Doody Dept of English Dept of English St Patrick’s College St Patrick’s College Drumcondra Drumcondra May 2010 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has-been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: Qoli |i/U i/|______________ ID No.: 55103316 Date: May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever indebted to Dr. Brenna Clarke for her ‘3-D’ vision, and all that she has so graciously taught me. A veritable fountain of knowledge, encouragement, and patient support, she- has-been a formative force to me, and will remain a true inspiration. Thank you appears paltry, yet it is deeply meant and intended as an expression of my profound gratitude. A sincere and heartfelt thank you is also extended to Dr. Noreen Doody for her significant contribution and generosity of time and spirit. Thank you also to Dr. Mary Shine Thompson, and the Research Office. A special note to Sharon, for her encyclopaedic knowledge and ‘inside track’ in negotiating the research minefield. This thesis is an acknowledgement of the efforts of my family, and in particular the constant support of my parents. -

Playbill 2004.., 2005 ~------~~------~~======~====~~~====~====~~==~~==~~~

The Village Theatre PLAYBILL 2004.., 2005 ~----------------------------------~~----------------------------------~~======================================~====~~~====~====~~==~~==~~~ College of Arts and Humanities James K. Johnson, Dean University Theatre Staff Recipients of Professors Excellence in Fine Arts Awards Clarence P. Blanchette Jerry Eisenhour Sponsored by the John T. Oertling, Chair David Wolski Newton E. Tarble Famjly Associate Professors Deb Althoff Jennifer Andrews Karen A. Eisenhour Brian Aycock Emily Betz Jean K. Wolski Nicholas Camfield Damen Edwards Caren Evers Bryan Grossbauer Assistant Professors Elisabeth Hartrich Robert Kalmbach Christopher J. Mitchell Theresa Lipinski Jessica Mahrt Robert S. Petersen Michael Papaleo Jennifer Pepsnik Ryan Peternell Scott Podraza Instructors Melissa Reczek Rocco Renda Allison Cameron Stacy Scherf Jeremy Seymour Mary E. Yarbrough Kate Slavinski Kyle Snyders Academic Support Professional Susan Sparacio Miranda Stone J. Sain Shawn Thompson Sarah Vecchio Emilie Weilbacher Christopher Yonke Specialists Joseph L. Allsion Tom Hawk Directed by C.P. Blanchette Secretary Damita K. Lewis A Theatre Arts Major is resident at EIU which includes concentrations in performance, design, and literature and directing A teacher certification option is available. For additional information call (217) 581-3121 or 581-3219 or visit the main office, 300 Lawson Hall EASTERN ILLNOIS UNIVERSITY THEATRE is a member of the Illinois Theatre Association, The Association for Theatre in Higher Education, Southeastern Theatre Conference, and is a participant in Region III of the American College Theatre Festival. Visit our website at http://www.eiu.edu/-theatre Warning - gun shots will be fired during the performance. All My Sons drama by Arthur Miller's Career in Brief Arthur Miller 1915 Born in New York 1937 They too Arise and No VIllain receive small awards 1944 The Man Who Had All the Luck is produced on Broadway Director ............................................................................................... -

100 Years on the Road, 108 a Christmas Carol, 390 a Cool Million, 57 a Memory of Two Mondays, 6, 129, 172, 173, 200, 211 a Natio

Cambridge University Press 0521844169 - Arthur Miller: A Critical Study Christopher Bigsby Index More information INDEX 100 Years on the Road,108 Ann Arbor, 12 Anna Karenina,69 A Christmas Carol,390 Anti-Semitism, 13, 14, 66, 294, 330, A Cool Million,57 476, 485, 488 AMemoryofTwoMondays,6,129,172, Apocalypse Now,272 173, 200, 211 Arden, John, 157 A Nation of Salesmen,107 Arendt, Hannah, 267, 325 APeriodofGrace, 127 Arnold, Eve, 225 A Search for a Future,453 Aronson, Boris, 251 A Streetcar Named Desire, 98, 106, 145 Artaud, Antonin, 283 A View from the Bridge, 157, 173, 199, Arthur Miller Centre, 404 200, 202, 203, 206, 209, 211, 226, Auschwitz–Birkenau, 250, 325, 329, 351, 459 471 Abel, Lionel, 483 Awake and Sing, 13, 57, 76 Actors Studio, 212 Aymee,´ Marcel, 154, 156 Adorno, Theodore, 326 After the Fall, 5, 64, 126, 135, 166, 203, ‘Babi Yar’, 488 209, 226, 227, 228, 248, 249, 250, Barry, Phillip, 18 257, 260, 264, 267, 278, 280, 290, Barton, Bruce, 427 302, 308, 316, 322, 327, 329, 331, BBC, 32 332, 333, 334, 355, 374, 378, 382, Beckett, Samuel, 120, 175, 199, 200, 386, 406, 410, 413, 415, 478, 487, 488 204, 209, 250, 263, 267, 325, 328, Alger, Horatio Jr., 57, 113 329, 387, 388, 410, 475 All My Sons,1,13,17,42,47,64,76,77, Bel-Ami,394 98, 99, 132, 136, 137, 138, 140, 197, Belasco, David, 175 288, 351, 378, 382, 388, 421, 432, 488 Bell, Daniel, 483 Almeida Theatre, 404, 416 Bellow, Saul, 74, 236, 327, 372, 376, Almost Everybody Wins,357 436, 470, 471, 472, 473, 483 American Clock, The, 337 Belsen, 325 American Federation of Labour, 47 -

International Research Journal of Commerce, Arts and Science Issn 2319 – 9202

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF COMMERCE, ARTS AND SCIENCE ISSN 2319 – 9202 An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust WWW.CASIRJ.COM www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions CASIRJ Volume 9 Issue 2 [Year - 2018] ISSN 2319 – 9202 Reflection of a new society in the works of Arthur Miller Ojasavi Research Scholar Singhania University,Pacheri, Jhunjhunu Analysis of writings of Arthur Asher Miller is one of the land mark in English literature. It not only increase the analytical capacity of a scholar but add some information in existing literature which increase the curiosity of the reader in concerned subject and leads to origin of new ideas. The present research concentrates on critical analysis of selected writings of Arthur Asher Miller with emphasis on circumstances under which ideas came in the mind. Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist, and prominent figure in twentieth-century American theatre. Among his most popular plays are All My Sons (1947), Death of a Salesman (1949), The Crucible (1953) and A View from the Bridge (1955, revised 1956). He also wrote several screenplays and was most noted for his work on The Misfits (1961). The drama Death of a Salesman is often numbered on the short list of finest American plays in the 20th century alongside Long Day's Journey into Night and A Streetcar Named Desire. Before proceeding forward about writings of Miller it is necessary to know about his life and society when he came in to public eye, particularly during the late 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s. -

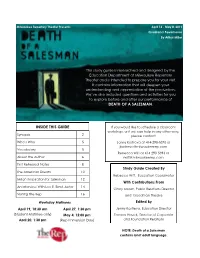

Death of a Salesman. Inside This Guide

Milwaukee Repertory Theater Presents April 12 - May 8, 2011 Quadracci Powerhouse By Arthur Miller This study guide is researched and designed by the Education Department at Milwaukee Repertory Theater and is intended to prepare you for your visit. It contains information that will deepen your understanding and appreciation of the production. We‘ve also included questions and activities for you to explore before and after our performance of DEATH OF A SALESMAN. INSIDE THIS GUIDE If you would like to schedule a classroom workshop, or if we can help in any other way, Synopsis 2 please contact Who‘s Who 5 Jenny Kostreva at 414-290-5370 or [email protected] Vocabulary 5 Rebecca Witt at 414-290-5393 or About the Author 6 [email protected] First Rehearsal Notes 8 Study Guide Created By The American Dream 10 Rebecca Witt, Education Coordinator Miller‘s Inspiration for Salesman 12 With Contributions From An Interview With Lee E. Ernst, Actor 14 Cindy Moran, Public Relations Director Visiting The Rep 16 and Goodman Theatre Weekday Matinees Edited By April 19, 10:30 am April 27, 1:30 pm Jenny Kostreva, Education Director (Student Matinee only) May 4, 12:00 pm Tamara Hauck, Director of Corporate April 20, 1:30 pm (Rep Immersion Day) and Foundation Relations NOTE: Death of a Salesman contains brief adult language. Page 2 SYNOPSIS *Spoiler Alert: This synopsis contains crucial plot because Biff is well-liked and Bernard is not. points. After Bernard leaves, Willy and Linda discuss how much Willy made from sales. They realize All Costume Renderings were drawn by Rachel that it‘s not quite enough to pay the bills, but Healy, Costume Designer. -

Arthur Miller Roxbury, Connecticut, Which Would Become His Long Time Home

Guild's National Award. During 1944 Miller toured army camps to collect background material for his 1945 screenplay, The Story of GI Joe. In 1947 Miller's Name play, All My Sons, was produced and won the New York Critics' Circle Award and two Tony Awards. As his success continued, Miller made the decision in 1948 to build a studio in Arthur Miller Roxbury, Connecticut, which would become his long time home. It was in this studio where he wrote the play that brought him international fame, Death of a By Jamie Kee Salesman. This play was considered a major achievement and has become a classic in American and world theatre. On February 10, 1949, the play premiered on Broadway at the Morosco Theatre. Miller's Death of a Salesman won a Tony Born on October 17, 1915, American playwright Award for best play, the New York City Drama Circle Critics' Award, and the Arthur Miller was a major figure in the American Pulitzer Prize for drama. This was the first time a play won all three of these major theatre and cinema. He was best known for his play, awards. Death of a Salesman, and for his marriage to actress Marilyn Monroe. Miller wrote other plays such as During the 1950s the United States Congress began investigating Communist The Crucible, A View from the Bridge, and All My influence in the arts. Miller compared these investigations to the witch trials of Sons, all of which are still performed and studied 1692, so he traveled to Salem, Massachusetts, to do research.