Parameters of Perception: Vision, Audition, and Twentieth-Century Music and Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listening to Dance...With Our Bodies and Minds Jordan

Interdisciplinary Panel 4: Looking and listening Listening to dance...with our bodies and minds Stephanie Jordan, Research Professor in Dance, Director of Centre for Dance Research, Roehampton University Through our bodies, we empathise not only with dance, but also with its accompanying music. So, what happens when we experience dance and music together, or ‘choreomusically’? Evidence now suggests that audio, visual and motor imagery share a common representational and neuropsychological base, even though music can be subversive as much as supportive in the partnership with dance. In this regard, might it be useful to explore the interface between perception and empathy in our discussion of dance and music? In experiencing dance and music together, is the response one of integration or of two (or even more) separate ‘voices’ or ‘bodies’, each of which invites empathetic response or ‘virtual motion’? My paper raises questions about how we respond to choreomusical structures, drawing from my experience of integrating ideas from cognitive science into dance analysis (independently and in experimental workshops). My research, though primarily from the point of view of perception, raises key questions about empathetic responses to, or embodiment of, the two simultaneously-presented media. Although a number of valuable crossmodal studies deal with basic temporal and spatial concepts, there are few to date that have foregrounded relations (or structural meetings) between the more complex and extended stimuli of actual dance and music. In the two seminal experiments (Krumhansl and Schenk (1997); Mitchell and Gallaher (2001)), empirical evidence demonstrated that dance can reflect musical formal divisions, pitch level, dynamics and emotions. -

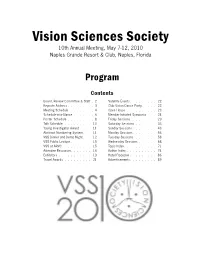

2010 Program Meeting Schedule

Vision Sciences Society 10th Annual Meeting, May 7-12, 2010 Naples Grande Resort & Club, Naples, Florida Program Contents Board, Review Committee & Staff . 2 Satellite Events. 22 Keynote Address . 3 Club Vision Dance Party. 22 Meeting Schedule . 4 Open House . 23 Schedule-at-a-Glance . 6 Member-Initiated Symposia . 24 Poster Schedule . 8 Friday Sessions . 29 Talk Schedule . 10 Saturday Sessions . 33 Young Investigator Award . 11 Sunday Sessions . 43 Abstract Numbering System. 11 Monday Sessions . 53 VSS Dinner and Demo Night . 12 Tuesday Sessions . 58 VSS Public Lecture . 15 Wednesday Sessions . 68 VSS at ARVO . 15 Topic Index. 71 Attendee Resources . 16 Author Index . 74 Exhibitors . 19 Hotel Floorplan . 86 Travel Awards . 21 Advertisements. 89 Board, Review Committee & Staff Board of Directors Abstract Review Committee Tony Movshon (2011), President David Alais Laurence Maloney New York University Marty Banks Ennio Mingolla Pascal Mamassian (2012), President Elect Irving Biederman Cathleen Moore CNRS & Université Paris 5 Geoff Boynton Shin’ya Nishida Eli Brenner Tony Norcia Bill Geisler (2010), Past President Angela Brown Aude Oliva University of Texas, Austin David Burr Alice O’Toole Marisa Carrasco (2012), Treasurer Patrick Cavanagh John Reynolds New York University Marvin Chun Anna Roe Barbara Dosher (2013) Jody Culham Brian Rogers University of California, Irvine Greg DeAngelis Jeff Schall James Elder Brian Scholl Karl Gegenfurtner (2013) Steve Engel David Sheinberg Justus-Liebig Universität Giessen, Germany Jim Enns Daniel Simons -

Cognition of Musical and Visual Accent Structure Alignment in Film and Animation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cognition of musical and visual accent structure alignment in film and animation A doctoral dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Scott David Lipscomb 1995 © Copyright by Scott David Lipscomb 1995 ii The dissertation of Scott David Lipscomb is approved. __________________________________________ Roger Bourland __________________________________________ Edward C. Carterette __________________________________________ William Hutchinson __________________________________________ James Thomas __________________________________________ Roger A. Kendall, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 1995 ii To my son, John David. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page # LIST OF FIGURES x LIST OF TABLES xiv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xvi VITA xvii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xix CHAPTER ONE—INTRODUCTION 1 Research Questions 2 Film Music Background 3 Purpose and Significance of the Study 6 Basic Assumptions 7 Delimitation 8 Hypotheses 9 CHAPTER TWO—RELATED LITERATURE 12 Proposed Model and Its Foundation 15 Musical and Visual Periodicity 17 The Communication of Musical Meaning 19 A 3-Dimensional Model of Film Classification 23 Accent Structure Alignment 26 Determinants of Accent 26 Sources of Musical Accent 29 Sources of Visual Accent 34 iv A Common Language 38 Potential Sources of Musical and Visual Accent in the Present Study 39 Mapping of Audio-Visual Accent Structures 41 CHAPTER THREE—METHOD 42 Research Design 42 Subject Selection 43 Stimulus -

Boundaries in Spatial Cognition: How They Look Is More Important Than What They Do

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/391037; this version posted August 13, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. SPATIAL CODING 1 Boundaries in Spatial Cognition: How They Look is More Important than What They Do James Negen1, Angela Sandri2, Sang Ah Lee3, Marko Nardini1 1Department of Psychology, Durham University, Durham, UK 2Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento, Rovereto, Italy 3Department of Bio and Brain Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon, Korea bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/391037; this version posted August 13, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. SPATIAL CODING 2 ABSTRACT Typical boundaries (e.g. large walls) strongly influence neural activity related to navigation and representations of spatial layouts. Typical boundaries are also a major aid to reliable navigation in young children and non-human animals. One hypothesis places this as a function of the walls being boundaries, defined by proponents as obstacles to navigation. An alternative hypothesis suggests that this is a function of visual covariates such as the presence of large 3D surfaces. Using immersive virtual reality, we dissociated whether walls in the environment were true boundaries (i.e., obstacles to navigation) or not (i.e., visually identical but not obstacles to navigation), or if they were replaced with smaller objects. 20 adults recalled locations of objects in virtual environments under four conditions: plywood, where a visual wall coincided with a large touchable piece of plywood; pass through, where the wall coincided with empty space and participants could pass through it; pass over, where the wall was underneath a transparent floor, and cones, where there were traffic cones instead of walls. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/201487 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-27 and may be subject to change. Rusz, D., et al. (2019). Do Reward-Related Distractors Impair Cognitive Performance? Perhaps Not. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1): 10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.169 ORIGINAL RESEARCH REPORT Do Reward-Related Distractors Impair Cognitive Performance? Perhaps Not Dorottya Rusz*, Erik Bijleveld† and Michiel A. J. Kompier† Over a hundred prior studies show that reward-related distractors capture attention. It is less clear, however, whether and when reward-related distractors affect performance on tasks that require cognitive control. In this experiment, we examined whether reward-related distractors impair performance during a demanding arithmetic task. Participants (N = 81) solved math problems, while they were exposed to task-irrelevant stimuli that were previously associated with monetary rewards (vs. not). Although we found some evidence for reward learning in the training phase, results from the test phase showed no evidence that reward-related distractors harm cognitive performance. This null effect was invariant across different versions of our task. We examined the results further with Bayesian analyses, which showed positive evidence for the null. Altogether, the present study showed that reward-related distractors did not harm performance on a mental arithmetic task. When considered together with previous studies, the present study suggests that the negative impact of reward-related distractors on cognitive control is not as straightforward as it may seem, and that more research is needed to clarify the circumstances under which reward-related distractors harm cognitive control. -

The Infant's Auditory World: Hearing, Speech, and the Beginnings Of

dam2_c02.qxd 1/6/06 12:44 PM Page 58 CHAPTER 2 The Infant’s Auditory World: Hearing, Speech, and the Beginnings of Language JENNY R. SAFFRAN, JANET F. WERKER, and LYNNE A. WERNER INFANT AUDITION 59 Stress and Phonotactic Cues 80 Development of the Auditory Apparatus: Higher-Level Units 81 Setting the Stage 59 LEARNING MECHANISMS 81 Measuring Auditory Development 60 Units for Computations 83 Frequency Coding 61 BUILDING FROM THE INPUT DURING THE Intensity Coding 63 1ST YEAR 83 Temporal Coding 67 Learning Phonology and Phonotactics 84 Spatial Resolution 69 Word Segmentation 84 Development of Auditory Scene Analysis 70 Beginnings of Word Recognition 88 Implications for theDevelopment of Listening for Meaning 89 Speech Perception 71 Beginnings of Grammar 91 INFANT SPEECH PERCEPTION AND WORD CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS 92 LEARNING: BEGINNINGS OF LANGUAGE 72 Relationship between Auditory Processing and Emergence of the Field: Phonetic Perception 72 Speech Perception 92 A Preference for Speech 75 Constraints on Learning 93 Perception of the Visible Information in Speech 76 Domain Specificity and Species Specificity 93 Perception of Prosodic Attributes of the The Infant’s Auditory World 94 Speech Signal 77 REFERENCES 95 Perception of Other Aspects of the Speech Signal 78 IMPLICIT DISCOVERY OF CUES IN THE INPUT: A DRIVE TO MAKE SENSE OF THE ENVIRONMENT 80 The auditory world provides a rich source of informa- tion provides a channel for many important sources of tion to be acquired by the developing infant. We are born inputs, including a variety of critical environmental with well-developed auditory systems, capable of gath- sounds such as music and spoken language. -

Parameters of Perception: Vision, Audition, and Twentieth-Century Music and Dance

AVANT, Vol. VIII, No. 1/2017 ISSN: 2082-6710 avant.edu.pl/en DOI: 10.26913/80102017.0101.0004 Parameters of Perception: Vision, Audition, and Twentieth-Century Music and Dance Allen Fogelsanger Kathleya Afanador SUNY Purchase College Conservatory of Dance Armadillo Dance Project allen.fogelsanger @ gmail.com kathleya @ armadillodanceproject.com Abstract Recent experimental psychological research on visual perception, auditory perception, and cross-modal perception has shed light on how these processes differ, and how the relations between visual and auditory stimuli shade our understanding of the events perceived. This work offers a possible way into considering the question of how music and dance “go together” or not, and particularly may shed light on the unusual twentieth-century human behavior of NOT having music and dance “go together.” Our paper presents relevant re- search in perception, examines factors contributing to the separation of perceptual modal- ities that has often appeared in twentieth-century dance, and discusses the separation in terms of the specific behaviors of dancing and looking at dance. Keywords: perception; vision; audition; music; dance We come to this paper with a practical interest in what makes music and dance go together, or not, in that one of us choreographs and one of us composes, and we share a desire to make computer-interactive pieces. In such pieces the connection between movement and sound must be examined explicitly, and this has led us to explore the literature from ex- perimental psychology relating sound to movement and attempt to connect it to the making and viewing of dances. We start by trying to distinguish between cases where dance and music are seen to “go together” and those where they are not. -

Ownership Illusions in Patients with Body Delusions: Different Neural Profiles of Visual Capture and Disownership

cortex xxx (2016) 1e12 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cortex Special issue: Research report Ownership illusions in patients with body delusions: Different neural profiles of visual capture and disownership Olivier Martinaud a,b,1, Sahba Besharati b,c,1,2, Paul M. Jenkinson d and * Aikaterini Fotopoulou b, a Department of Neurology, Rouen University Hospital, France b Clinical, Educational & Health Psychology Research Department, Division of Psychology & Language Sciences, University College London, UK c Academic Unit of Neuropsychiatry, King's College London, UK d School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, UK article info abstract Article history: The various neurocognitive processes contributing to the sense of body ownership have Received 9 April 2016 been investigated extensively in healthy participants, but studies in neurological patients Reviewed 24 May 2016 can shed unique light into such phenomena. Here, we aimed to investigate whether visual Revised 22 July 2016 capture by a fake hand (without any synchronous or asynchronous tactile stimulation) Accepted 25 September 2016 affects body ownership in a group of hemiplegic patients with or without disturbed Published online xxx sensation of limb ownership (DSO) following damage to the right hemisphere. We recruited 31 consecutive patients, including seven patients with DSO. The majority of our patients Keywords: (64.5% overall and up to 86% of the patients with DSO) experienced strong feelings of Anosognosia for hemiplegia ownership over a rubber hand within 15 sec following mere visual exposure, which Asomatognosia correlated with the degree of proprioceptive deficits across groups and in the DSO group. -

Cognition of Musical and Visual Accent Structure Alignment in Film and Animation

PRE-PUBLICATION DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT PHOTOCOPY THE PERCEPTION OF AUDIO-VISUAL COMPOSITES: ACCENT STRUCTURE ALIGNMENT OF SIMPLE STIMULI Scott D. Lipscomb Northwestern University In contemporary society, the human sensory system is bombarded by sounds and images intended to attract attention, manipulate state of mind, or affect behavior.1 Patients awaiting a medical or dental appointment are often subjected to the "soothing" sounds of Muzak as they sit in the waiting area. Trend-setting fashions are displayed in mall shops blaring the latest Top 40 selec- tions to attract their specific clientele. Corporate training sessions and manage- ment presentations frequently employ not only communication through text and speech, but a variety of multimedia types for the purpose of attracting and main- taining attention, e.g. music, graphs, and animation. Recent versions of word processors allow the embedding of sound files, animations, charts, equations, pictures, and information from multiple applications within a single document. Even while standing in line at an amusement park or ordering a drink at the local pub, the presence of television screens providing aural and visual "companion- ship" is now ubiquitous. In each of these instances mentioned, music is assumed to be a catalyst for establishing the mood deemed appropriate, generating desired actions, or simply maintaining a high level of interest among participants within a given context. Musical affect has also been claimed to result in increased labor produc- tivity and reductions in on-the-job accidents when music is piped into the work- place (Hough, 1943; Halpin, 1943-4; Kerr, 1945), though these studies are often far from rigorous in their method and analysis (McGehee & Gardner, 1949; Car- dinell & Burris-Meyer, 1949; Uhrbock, 1961). -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/201487 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-01-04 and may be subject to change. Rusz, D., et al. (2019). Do Reward-Related Distractors Impair Cognitive Performance? Perhaps Not. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1): 10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.169 ORIGINAL RESEARCH REPORT Do Reward-Related Distractors Impair Cognitive Performance? Perhaps Not Dorottya Rusz*, Erik Bijleveld† and Michiel A. J. Kompier† Over a hundred prior studies show that reward-related distractors capture attention. It is less clear, however, whether and when reward-related distractors affect performance on tasks that require cognitive control. In this experiment, we examined whether reward-related distractors impair performance during a demanding arithmetic task. Participants (N = 81) solved math problems, while they were exposed to task-irrelevant stimuli that were previously associated with monetary rewards (vs. not). Although we found some evidence for reward learning in the training phase, results from the test phase showed no evidence that reward-related distractors harm cognitive performance. This null effect was invariant across different versions of our task. We examined the results further with Bayesian analyses, which showed positive evidence for the null. Altogether, the present study showed that reward-related distractors did not harm performance on a mental arithmetic task. When considered together with previous studies, the present study suggests that the negative impact of reward-related distractors on cognitive control is not as straightforward as it may seem, and that more research is needed to clarify the circumstances under which reward-related distractors harm cognitive control. -

Sensation and Perception

Sensation and Perception OUTLINE OF RESOURCES Introducing Sensation and Perception Podcast/Lecture/Discussion Topic: Person Perception (p. 3) UPDATED Basic Principles of Sensation and Perception Lecture/Discussion Topics: Sensation Versus Perception (p. 4) Top-Down Processing (p. 5) “Thin-Slicing” (p. 6) Classroom Exercises: A Scale to Assess Sensory-Processing Sensitivity (p. 6) UPDATED Human Senses Demonstration Kits (p. 6) UPDATED Classroom Exercises/Student Projects: The Wundt-Jastrow Illusion (p. 4) LaunchPad Video: The Man Who Cannot Recognize Faces* Thresholds Lecture/Discussion Topics: Gustav Fechner and Psychophysics (p. 7) Subliminal Smells (p. 8) Subliminal Persuasion (p. 9) Applying Weber’s Law (p. 10) Student Projects: The Variability of the Absolute Threshold (p. 8) Understanding Weber’s Law (p. 9) Sensory Adaptation Student Project: Sensory Adaptation (p. 10) UPDATED Classroom Exercises: Eye Movements (p. 10) Sensory Adaptation in the Marketplace (p. 11) Perceptual Set Lecture/Discussion Topic: Do Red Objects Feel Warmer or Colder Than Blue Objects? (p. 11) NEW Classroom Exercises: Perceptual Set (p. 11) UPDATED Perceptual Set and Gender Stereotypes (p. 12) Context Effects (see also Brightness Contrast, p. 22) Lecture/Discussion Topic: Context and Perception (p. 13) Vision: Sensory and Perceptual Processing Classroom Exercise/Student Project: Physiology of the Eye—A CD-ROM for Teaching Sensation and Perception (p. 13) LaunchPad Video: Vision: How We See* The Eye and the Stimulus Input Lecture/Discussion Topic:Classroom as Eyeball (p. 13) Student Projects: Color the Eyeball (p. 13) NEW Locating the Retinal Blood Vessels (p. 13) Student Projects/Classroom Exercises: Rods, Cones, and Color Vision (p. 14) UPDATED Locating the Blind Spot (p. -

Temporal Auditory Capture Does Not Affect the Time Course of Saccadic Mislocalization of Visual Stimuli

Journal of Vision (2010) 10(2):7, 1–13 http://journalofvision.org/10/2/7/ 1 Temporal auditory capture does not affect the time course of saccadic mislocalization of visual stimuli Department of Psychology, Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Milano, Italy,& Italian Institute of Technology, IIT Network, Research Unit of Paola Binda Molecular Neuroscience, Genova, Italy Department of Physiological Sciences, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy,& M. Concetta Morrone Scientific Institute Stella Maris, Calambrone, Pisa, Italy Department of Psychology, Università Degli Studi di Firenze, Firenze, Italy, CNR Neuroscience Institute, Pisa, Italy,& Department of Psychology, University of Western Australia, David C. Burr Stirling Hw., Nedlands, Perth, Western Australia, Australia Irrelevant sounds can “capture” visual stimuli to change their apparent timing, a phenomenon sometimes termed “temporal ventriloquism”. Here we ask whether this auditory capture can alter the time course of spatial mislocalization of visual stimuli during saccades. We first show that during saccades, sounds affect the apparent timing of visual flashes, even more strongly than during fixation. However, this capture does not affect the dynamics of perisaccadic visual distortions. Sounds presented 50 ms before or after a visual bar (that change perceived timing of the bars by more than 40 ms) had no measurable effect on the time courses of spatial mislocalization of the bars, in four subjects. Control studies showed that with barely visible, low-contrast stimuli, leading, but not trailing, sounds can have a small effect on mislocalization, most likely attributable to attentional effects rather than auditory capture. These findings support previous studies showing that integration of multisensory information occurs at a relatively late stage of sensory processing, after visual representations have undergone the distortions induced by saccades.