The Ballets of Daniel-François-Esprit Auber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel-François-Esprit AUBER Overtures • 4 Le Duc D’Olonne Fra Diavolo Le Philtre Actéon Divertissement De Versailles

Daniel-François-Esprit AUBER Overtures • 4 Le Duc d’Olonne Fra Diavolo Le Philtre Actéon Divertissement de Versailles Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra Dario Salvi Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (1782 –1871) aristocrats, Lord Cockburn and Lady Pamela, great comic from the Act I trio for Thérèsine, Jolicoeur and Guillaume creations. The Overture begins with the quiet beat of a predominating: Jolicoeur’s opening strutting military Overtures • 4 2 side drum, and gradually the whole orchestra joins in, dotted rhythms, Guillaume’s assertion of his faith in the Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, a beautiful name to conjure Act II: Entr’acte et Introduction (Allegro, C major, 3/4) creating the effect of an approaching procession which efficacy of the philtre with its characteristic leaping fifths, with, was one of the most famous composers of the 19th then passes on into the distance. A trumpet call initiates a the conclusion of the trio in thirds – a proleptic suggestion century. Working with his lifelong collaborator, the A drum beat initiates a military march, slightly chromatic, strenuous passage, leading into a sprightly tune for the of the union of Thérèsine and Guillaume. The opera renowned dramatist and librettist Eugène Scribe (1791– with strong brass. A figure adapted from the Overture with woodwind over pizzicato strings, followed by a dance-like remained popular in Paris until 1862, with 243 performances. 1861), he gave definitive form to the uniquely French woodwinds in thirds is briefly developed, and repeated as section for the whole orchestra. Both these themes come 7 genres of grand historical opera ( La Muette de Portici ) and a full orchestral statement. -

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon Du Diable

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable, Edited by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3608-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3608-1 Cesare Pugni in London (c. 1845) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................... ix Esmeralda Italian Version La corte del miracoli (Introduzione) .......................................................................................... 2 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................. 5 Sposalizio di Esmeralda ............................................................................................................. 6 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................ -

Spring Performances Celebrate Class of 2018

Fall 2018 Spring Performances Celebrate Class of 2018 The Morris and Elfriede Stonzek Spring Performances, presented last May, served as a fitting celebration of the 2018 graduating class and a wonderful way to kick off Memorial Day weekend. In keeping with tradition, the performances opened with a presentation of the fifteen seniors who would receive their diplomas the following week—HARID’s largest-ever graduating class. Alex Srb photo © Srb photo Alex The program opened with The Fairy Doll Pas de Trois, staged by Svetlana Osiyeva and Meelis Pakri. Catherine Alex Srb © Alex Doherty sparkled as the fairy doll, in an exquisite pink tutu, while David Rathbun and Jaysan Stinnett (cast as the two A scene from the Black Swan Pas de Deux, Swan Lake, Act III pierrots competing for her attention) accomplished the challenging technical elements of the ballet while endearingly portraying their comedic characters. The next work on the program was the premiere of It Goes Without Saying, choreographed for HARID by resident choreographer Mark Godden. Set to music by Nico Muhly and rehearsed by Alexey Kulpin, this work stretched the artistic scope of the dancers by requiring them to speak on stage and move in unison to music that is not always melodically driven. The ballet featured a haunting pas de Alex Srb photo © Srb photo Alex deux, performed maturely by Anna Gonzalez and Alexis Alex Srb © Alex Valdes, and a spirited, playful duet for dancers Tiffany Chatfield and Chloe Crenshaw. The Fairy Doll Pas de Trois The second half of the program featured Excerpts from Swan Lake, Acts I and III. -

Incorporare Il Fantastico: Marie Taglioni Elena Cervellati ([email protected])

* Incorporare il fantastico: Marie Taglioni Elena Cervellati ([email protected]) Il balletto fantastico e Marie Taglioni Negli anni Trenta dell'Ottocento in alcuni grandi teatri istituzionali europei fioriscono balletti in grado di raccogliere e fare precipitare in una forma visibile istanze che percorrono, proprio in quegli anni, diversi ambiti della cultura, della società, del sentire, consolidando e facendo diventare norma un certo modo di trovare temi e personaggi, di strutturare tessuti drammaturgici, di costruire il mondo in cui l'azione si svolgerà, di danzare. Mondi altri con cui chi vive sulla terra può entrare in relazione, passaggi dallo stato di veglia a sogni densi di avvenimenti, incantesimi e malefici, esseri fatti di nebbia e di luce, ombre e spiriti impalpabili, creature volanti, esseri umani che assumono sembianze animali, oggetti inanimati che prendono vita e forme antropomorfe trovano nello spettacolo coreico e nel corpo danzante di quegli anni un luogo di elezione, andando a costituire uno dei tratti fondamentali del balletto romantico. Il danzatore abita i mondi proposti dalla “magnifica evasione” 1 offerta dal balletto e ne è al tempo stesso creatore primo. È capace di azioni sorprendenti, analoghe a quelle dell’acrobata che “poursuit sa propre perfection à travers la réussite de l’acte prodigieux qui met en valeur toutes les ressources de son corps”2. Lo stesso corpo * Il presente saggio è in corso di pubblicazione in Pasqualicchio, Nicola (a cura di), La meraviglia e la paura. Il fantastico nel teatro europeo (1750-1950) , atti del convegno, Università degli Studi di Verona, Verona, 10-11 marzo 2011. 1 Susan Leigh Foster, Coreografia e narrazione , Roma, Dino Audino Editore, 2003, p. -

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

QCF Examinations Information, Rules & Regulations

Specifications for qualifications regulated in England, Wales and Northern Ireland incorporating information, rules and regulations about examinations, class awards, solo performance awards, presentation classes and demonstration classes This document is valid from 1 July 2018 1 The Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) is an international teacher education and awarding organisation for dance. Established in 1920 as the Association of Operatic Dancing of Great Britain, it was granted a Royal Charter in 1936 and renamed the Royal Academy of Dancing. In 1999 it became the Royal Academy of Dance. Vision Leading the world in dance education and training, the Royal Academy of Dance is recognised internationally for the highest standards of teaching and learning. As the professional membership body for dance teachers it inspires and empowers dance teachers and students, members, and staff to make innovative, artistic and lasting contributions to dance and dance education throughout the world. Mission To promote and enhance knowledge, understanding and practice of dance internationally by educating and training teachers and students and by providing examinations to reward achievement, so preserving the rich, artistic and educational value of dance for future generations. We will: communicate openly collaborate within and beyond the organisation act with integrity and professionalism deliver quality and excellence celebrate diversity and work inclusively act as advocates for dance. Examinations Department Royal Academy of Dance 36 Battersea Square London SW11 3RA Tel +44 (0)20 7326 8000 [email protected] www.rad/org.uk/examinations © Royal Academy of Dance 2017 ROYAL ACADEMY OF DANCE, RAD, and SILVER SWANS are registered trademarks® of the Royal Academy of Dance in a number of jurisdictions. -

Romantic Ballet

ROMANTIC BALLET FANNY ELLSLER, 1810 - 1884 SHE ARRIVED ON SCENE IN 1834, VIENNESE BY BIRTH, AND WAS A PASSIONATE DANCER. A RIVALRY BETWEEN TAGLIONI AND HER ENSUED. THE DIRECTOR OF THE PARIS OPERA DELIBERATELY INTRODUCED AND PROMOTED ELLSLER TO COMPETE WITH TAGLIONI. IT WAS GOOD BUSINESS TO PROMOTE RIVALRY. CLAQUES, OR PAID GROUPS WHO APPLAUDED FOR A PARTICULAR PERFORMER, CAME INTO VOGUE. ELLSLER’S MOST FAMOUS DANCE - LA CACHUCHA - A SPANISH CHARACTER NUMBER. IT BECAME AN OVERNIGHT CRAZE. FANNY ELLSLER TAGLIONI VS ELLSLER THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN TALGIONI AND ELLSLER: A. TAGLIONI REPRESENTED SPIRITUALITY 1. NOT MUCH ACTING ABILITY B. ELLSLER EXPRESSED PHYSICAL PASSION 1. CONSIDERABLE ACTING ABILITY THE RIVALRY BETWEEN THE TWO DID NOT CONFINE ITSELF TO WORDS. THERE WAS ACTUAL PHYSICAL VIOLENCE IN THE AUDIENCE! GISELLE THE BALLET, GISELLE, PREMIERED AT THE PARIS OPERA IN JUNE 1841 WITH CARLOTTA GRISI AND LUCIEN PETIPA. GISELLE IS A ROMANTIC CLASSIC. GISELLE WAS DEVELOPED THROUGH THE PROCESS OF COLLABORATION. GISELLE HAS REMAINED IN THE REPERTORY OF COMPANIES ALL OVER THE WORLD SINCE ITS PREMIERE WHILE LA SYLPHIDE FADED AWAY AFTER A FEW YEARS. ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR BALLETS EVER CREATED, GISELLE STICKS CLOSE TO ITS PREMIER IN MUSIC AND CHOREOGRAPHIC OUTLINE. IT DEMANDS THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF TECHNICAL SKILL FROM THE BALLERINA. GISELLE COLLABORATORS THEOPHILE GAUTIER 1811-1872 A POET AND JOURNALIST HAD A DOUBLE INSPIRATION - A BOOK BY HEINRICH HEINE ABOUT GERMAN LITERATURE AND FOLK LEGENDS AND A POEM BY VICTOR HUGO-AND PLANNED A BALLET. VERNOY DE SAINTS-GEORGES, A THEATRICAL WRITER, WROTE THE SCENARIO. ADOLPH ADAM - COMPOSER. THE SCORE CONTAINS MELODIC THEMES OR LEITMOTIFS WHICH ADVANCE THE STORY AND ARE SUITABLE TO THE CHARACTERS. -

Verdian Musicodramatic Expression in Un Ballo in Maschera

VERDIAN MUSICODRAMATIC EXPRESSION IN UN BALLO IN MASCHERA A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTERS OF MUSIC BY JERRY POLMAN DR. CRAIG PRIEBE – ADVISER BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 | 1 On September 19, 1857, Giuseppe Verdi wrote to the impresario at San Carlo that he was “in despair.” He was commissioned to write an opera for the 1858 carnival season but could not find what he deemed a suitable libretto. For many years he desired to compose an opera based on Shakespeare‟s King Lear but he deemed the singers in Naples to be inadequate for the task. Nevertheless, he writes in the same letter that he is now “…condensing a French drama, Gustave III di Svezia, libretto by Scribe, given at the [Paris Grand Opéra with music by Auber] about twenty years ago [1833]. It is grand and vast; it is beautiful; but this too has the conventional forms of all works for music, something which I have never liked and I now find unbearable. I repeat, I am in despair, because it is too late to find other subjects.”1 Despite finding it “unbearable” Verdi continued to work on Gustave, calling on the talents of Antonia Somma to write the libretto. However, Verdi did not foresee the intense scrutiny that would be leveled against it. Upon receiving word from Vincenzo Torelli (the impresario of the San Carlo Opera House), that nothing less than a new production would suffice to fulfill his contract, Verdi and Somma set to work immediately on Gustave. -

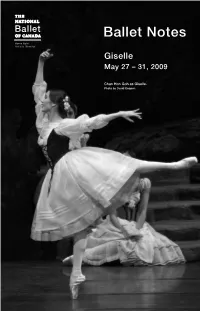

Ballet Notes Giselle

Ballet Notes Giselle May 27 – 31, 2009 Chan Hon Goh as Giselle. Photo by David Cooper. 2008/09 Orchestra Violins Clarinets • Fujiko Imajishi, • Max Christie, Principal Souvenir Book Concertmaster Emily Marlow, Lynn Kuo, Acting Principal Acting Concertmaster Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet On Sale Now in the Lobby Dominique Laplante, Bassoons Principal Second Violin Stephen Mosher, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., Founder James Aylesworth, Jerry Robinson Featuring beautiful new images Acting Assistant Elizabeth Gowen, George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Concertmaster by Canadian photographer Contra Bassoon Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Jennie Baccante Sian Richards Artistic Director Executive Director Sheldon Grabke Horns Xiao Grabke Gary Pattison, Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Nancy Kershaw Vincent Barbee Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Derek Conrod Principal Conductor • Csaba Koczó • Scott Wevers Yakov Lerner Trumpets Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Jayne Maddison Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Richard Sandals, Principal Ron Mah YOU dance / Ballet Master Mark Dharmaratnam Aya Miyagawa Raymond Tizzard Aleksandar Antonijevic, Guillaume Côté, Wendy Rogers Chan Hon Goh, Greta Hodgkinson, Filip Tomov Trombones Nehemiah Kish, Zdenek Konvalina, Joanna Zabrowarna David Archer, Principal Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Paul Zevenhuizen Robert Ferguson David Pell, Piotr Stanczyk, Xiao Nan Yu Violas Bass Trombone Angela Rudden, Principal Victoria Bertram, Kevin D. Bowles, Theresa Rudolph Koczó, Tuba -

Giselle Saison 2015-2016

Giselle Saison 2015-2016 Abonnez-vous ! sur www.theatreducapitole.fr Opéras Le Château de Barbe-Bleue Bartók (octobre) Le Prisonnier Dallapiccola (octobre) Rigoletto Verdi (novembre) Les Caprices de Marianne Sauguet (janvier) Les Fêtes vénitiennes Campra (février) Les Noces de Figaro Mozart (avril) L’Italienne à Alger Rossini (mai) Faust Gounod (juin) Ballets Giselle Belarbi (décembre) Coppélia Jude (mars) Paradis perdus Belarbi, Rodriguez (avril) Paquita Grand Pas – L’Oiseau de feu Vinogradov, Béjart (juin) RCS TOULOUSE B 387 987 811 - © Alexander Gouliaev - © B 387 987 811 TOULOUSE RCS Giselle Midis du Capitole, Chœur du Capitole, Cycle Présences vocales www.fnac.com Sur l’application mobile La Billetterie, et dans votre magasin Fnac et ses enseignes associées www.theatreducapitole.fr saison 2015/16 du capitole théâtre 05 61 63 13 13 Licences d’entrepreneur de spectacles 1-1052910, 2-1052938, 3-1052939 THÉÂTRE DU CAPITOLE Frédéric Chambert Directeur artistique Janine Macca Administratrice générale Kader Belarbi Directeur de la danse Julie Charlet (Giselle) et Davit Galstyan (Albrecht) en répétition dans Giselle, Ballet du Capitole, novembre 2015, photo David Herrero© Giselle Ballet en deux actes créé le 28 juin 1841 À l’Académie royale de Musique de Paris (Salle Le Peletier) Sur un livret de Théophile Gautier et de Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges D’après Heinrich Heine Nouvelle version d’après Jules Perrot et Jean Coralli (1841) Adolphe Adam musique Kader Belarbi chorégraphie et mise en scène Laure Muret assistante-chorégraphe Thierry Bosquet décors Olivier Bériot costumes Marc Deloche architecte-bijoutier Sylvain Chevallot lumières Monique Loudières, Étoile du Ballet de l’Opéra National de Paris maître de ballet invité Emmanuelle Broncin et Minh Pham maîtres de ballet Nouvelle production Ballet du Capitole Kader Belarbi direction Orchestre national du Capitole Philippe Béran direction Durée du spectacle : 2h25 Acte I : 60 min. -

Le Cheval De Bronze De Daniel Auber

GALERÍA DE RAREZAS Le cheval de bronze de Daniel Auber por Ricardo Marcos oy exploraremos una sala encantadora, generosamente iluminada, con grandes mesas en donde podemos degustar algunos de los chocolates franceses más sofisticados y deliciosos, de esta galería de rarezas operísticas. El compositor en cuestión gozó de la gloria operística y fue el segundo director en la historia del Conservatorio de París. Su Hmusa es ligera e irresistible, si bien una de sus grandes creaciones es una obra dramática. Durante la década de 1820 París se convirtió en el centro del mundo musical gracias en gran medida a tres casas de ópera emblemáticas; La Opéra de Paris, la Opéra Comique y el Thêatre Italien. Daniel Auber, quien había estudiado con Luigi Cherubini, se convirtió en el gran señor de la ópera cómica y habría de ser modelo para compositores como Adolphe Adam, Francois Bazin y Victor Masse, entre otros. Dotado desde pequeño para la música, Auber había aprendido a tocar violín y el piano pero fue hasta 1811 en que perfeccionó sus estudios musicales y se dedicó de tiempo completo a la composición. Entre sus mejores obras dentro del campo de la ópera cómica se encuentran joyas como Fra Diavolo y Le domino noir; sin embargo, hay una obra más para completar un trío de obras maestras que, junto con las grandes óperas La muette de Portici, Haydée y Gustave III, conforman lo mejor de su producción. Estrenada el 23 de marzo de 1835, con un libreto de Eugène Scribe, el sempiterno libretista francés de la primera mitad del siglo XIX, El caballo de bronce es una obra deliciosa por la vitalidad de sus duetos, ensambles y la gracia de sus arias, muchas de ellas demandantes; con dos roles brillantes para soprano, uno para tenor, uno para barítono y uno para bajo. -

Marie Taglioni, Ballerina Extraordinaire: in the Company of Women

NINETEENTH-CENTURY GENDER STUDIES # ISSUE 6.3 (WINTER 2010) Marie Taglioni, Ballerina Extraordinaire: In the Company of Women By Molly Engelhardt, Texas A&M University—Corpus Christi <1>The nineteenth-century quest for novelty during the 1830s and 40s was nowhere better satisfied than from the stages of the large theatres in London and Paris, which on a tri-weekly basis showcased ballet celebrities and celebrity ballets as top fare entertainment.(1) While few devotees had the means to actually attend ballet performances, the interested majority could read the plots and reviews of the ballets published in print media—emanating from and traversing both sides of the channel—and know the dancers, their personalities and lifestyles, as well as the dangers they routinely faced as stage performers. During a benefit performance in Paris for Marie Taglioni, for example, two sylphs got entangled in their flying harnesses and audiences watched in horror as a stagehand lowered himself from a rope attached to the ceiling to free them. Théophile Gautier writes in his review of the performance that when Paris Opera director Dr. Veron did nothing to calm the crowds, Taglioni herself came to the footlights and spoke directly to the audience, saying “Gentlemen, no one is hurt.”(2) On another occasion a cloud curtain came crashing down unexpectedly and almost crushed Taglioni as she lay on a tombstone in a cloisture scene of Robert le Diable.(3) Reporters wrote that what saved her were her “highly- trained muscles,” which, in Indiana Jones fashion, she used to bound off the tomb just in time.